Of all the exhibitions seen at the Scuderie del Quirinale, perhaps The Universal Museum. From Napoleon’s Dream to Canova is the most ambitious, and certainly one of the most appealing to a public eager to break out of the logic of the blockbuster exhibition, to which sometimes even the Roman exhibition venue has not renounced, alternating sophisticated (but not for this reason inaccessible) exhibitions with others that are undeniably coarser. But, of course, it is not only in the quality of the proposal that lies the interest of an exhibition that intends to start from a theme, that of the recovery of Italian works that ended up in France following Napoleon’s requisitions, which is much more complex than one might imagine. Not least because the curators have well thought out to go into various topics (recovery tout court is but one of the “ingredients” that concur to form the layout of the exhibition), from the establishment of the first public picture galleries to the birth of the concept of the work of art as an asset endowed no longer only with material value but also with a high symbolic value. A value, it should be emphasized for a more correct historical framing of the events that affected Italy in those years, recognized as much by the French occupiers (for whom the works, as will be seen in the exhibition, were not just mere spoils of war, but above all a useful tool for the education of citizens) as by the inhabitants of the occupied Italian territories, who were beginning to manifest widely the signs of a cultural identity capable of uniting all of future Italy (although such manifestations came mostly from the educated elites ) and to understand that art had a public value of extraordinary importance.

There is one room in particular (the eighth of the ten that make up the exhibition’s itinerary), which offers tangible evidence of authentic rebellions of entire communities that occurred where someone had ventured to manifest an intention to surrender a work of art outside the sphere in which it had been produced, thus depriving the citizens of it. The pride of the latter, the fact that communities were also beginning to identify themselves with their artistic heritage, and the consciousness that was beginning to push villagers or townspeople to recognize the works as pieces of a “cultural heritage felt as a common good and a resource for the community” (so in the catalog Valter Curzi, curator of the exhibition together with Carolina Brook and Claudio Parisi Presicce) decisively prevented the alienation of assets that, thanks to such a common feeling, are still preserved today in the places that saw them come into being. This is the case, for example, with a Madonna and Child with Saints, a work by Giovanni Santi whose attempted transfer was thwarted by a nobleman from the Marche region, Count Pompeo Benedetti di Montevecchio, and was finally blocked by the papal authorities (reason why the painting was allowed to remain in the Marche region), or with a Madonna and Child with Saints Francis and Bernardine of Siena, a panel painting from 1458 by the Umbrian painter Niccolò di Liberatore (also known as Niccolò l’Alunno): was the central compartment of a polyptych made as an ex voto after a plague and subsequently dismembered, and being the only part left following the dismemberment, the community of Deruta, the village in which the work was located, firmly opposed the sale attempted by the Franciscan convent that guarded it and spent money to have the painting first restored by the municipality and then placed in the local church of San Francesco (today it is still in Deruta, but in the Pinacoteca Comunale). Historical evidence of a collective attachment to art whose rise was being witnessed.

|

| Giovanni Santi, Madonna and Child with Saints Helen, Zachary, Sebastian and Roch (c. 1484-1489; tempera on panel, 221 x 186 cm; Fano, Pinacoteca del Palazzo Malatestiano) |

|

| Niccolò di Liberatore known as the Pupil, Madonna and Child with Saints Francis and Bernardine of Siena (1458; tempera on panel, 234 x 144 cm; Deruta, Pinacoteca Comunale) |

The carnet of the exhibition becomes, in short, particularly dense, and the exhibition runs the risk of generating some confusion in the visitor, also because one must consider that the title is slightly misleading. Indeed, the latter undoubtedly makes anapproximation by default: the “universal museum” is not the central and exclusive subject of the exhibition. This reduction, however, is softly remedied by the expression “from Napoleon to Canova” chosen for the subtitle: although we are faced with what appears to be a well-established habit (we are literally overwhelmed by “from this to that” exhibitions), it cannot be denied that the “from... to,” in this case, responds well to the need to circumscribe the scope of the exhibition by fixing two poles that take on the burden of supporting its scaffolding. Napoleon: the spoliations, the idea of forming a natural “universal museum” in Paris as a product of the Age of Enlightenment that could gather together all the best of European artistic production, the equation that “culture” equals “freedom” (the concept may seem paradoxical when framed in the context of a military occupation, but for the French of the time it had a meaning that we will say more about in a moment). Canova: the recovery of the works and the return of them to their former owners when possible (with the consequent fading of those aspirations to universality that had moved the action of the French commissioners), the idea of an Italy “one of arms, language, altar, memories, blood and heart” (the Venetian sculptor, having promoted the creation of a series of busts of great Italian artists to be placed in the Pantheon, examples of which we have in the last room, can be considered a de facto supporter of the Manzonian assumption), the identity value of works of art, greeted by jubilation when they returned. In between: the birth of picture galleries, art to awaken consciences, the classics of the past as an example for the generations of the present (for artists, but also for anyone else).

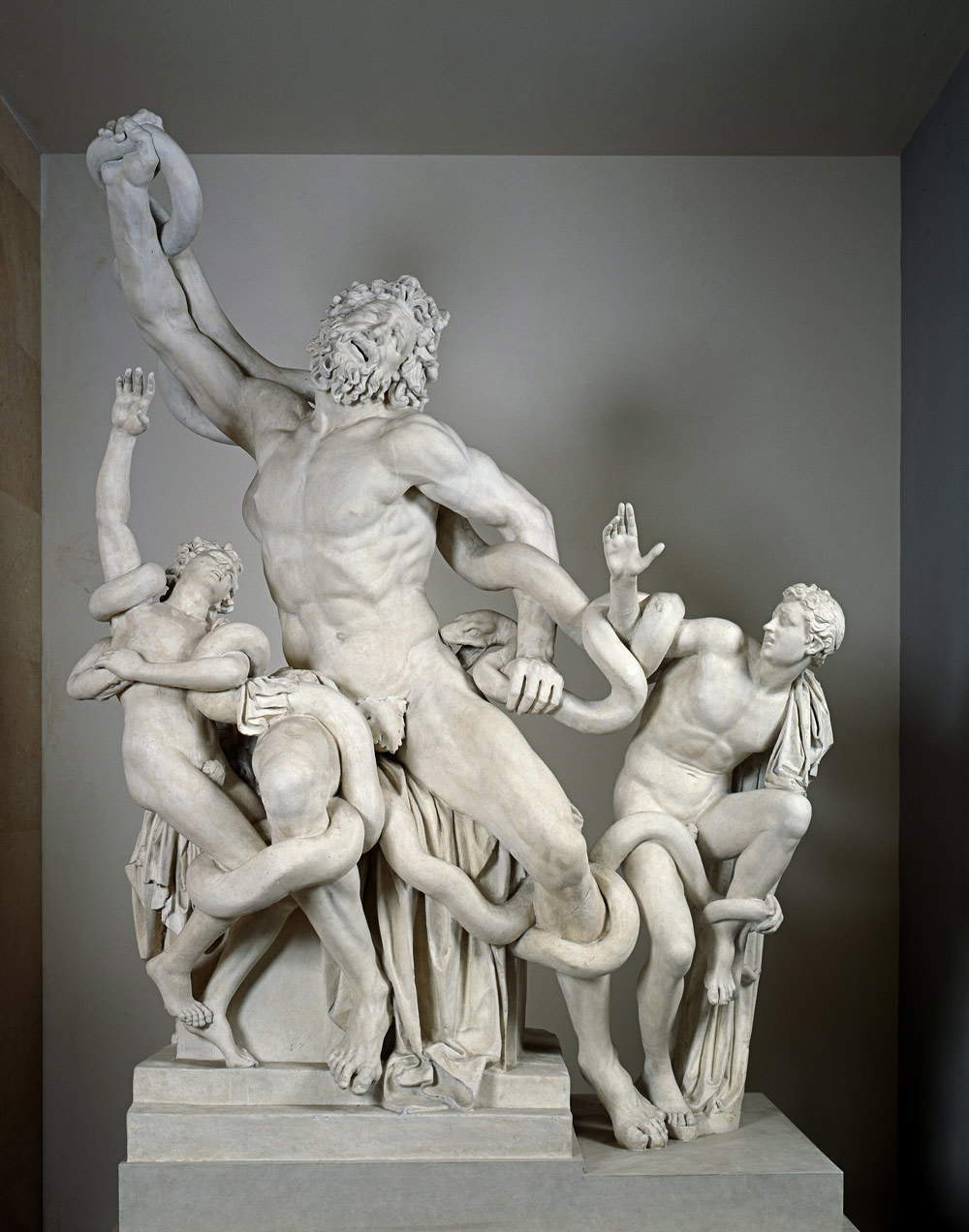

The narrative, however, starts with Canova and ends with Canova. The artist was one of the commissioners sent to France in order to recover works stolen by the French during their occupation: in this case, he was the commissioner appointed by the Papal States, under the papacy of Pius VII. It should be emphasized that recovery was anything but easy business. Not only because the expropriations had reached considerable proportions and there were, therefore, objective difficulties in the operations of census, identification and recovery. But also because Europe (this was 1815) was coming from an abundant decade of wars, the balances had been upset and international diplomacy was moving on particularly delicate terrain (so much so that to facilitate Canova’s work even King George IV of England intervened, who in order to strengthen diplomatic relations with the papacy had offered an important economic contribution destined for the recovery of the works that had taken the road to France). It took two years to see most of the works returned to their rightful place. Not all of them made it home, and the diplomatic skill of the commissioners was decisive in this regard. The first room of The Universal Museum thus pays homage to the Canova-Giorgio IV axis with portraits of the two figures and displays some of the works that could be returned: among them, the celebrated Laocoon group (a plaster cast is on display), which moreover faced a rather painful journey since it suffered, due to adverse weather conditions, a break on the Mont Cenis, and Guido Reni’s Slaughter of the Innocents, which represents one of the most important loans (if not the most important loan in absolute terms) of the entire exhibition.

|

| Guido Reni’s Slaughter of the Innocents and the cast of the Laocoon |

|

| Guido Reni, Strage degli Innocenti (1611; oil on canvas, 268 x 170 cm; Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

|

| Cast of the Laocoon (19th century?; plaster, 205 x 158 x 105 cm; Rome, Vatican City, Vatican Museums) |

The next rooms on the second floor of the Scuderie del Quirinale investigate the whys of the spoliations and the reasons why the French commissioners chose certain artists over others (the visual director is marked by a relaxing azure blue that accompanies the visitor along the first five rooms of the itinerary). The French justified the looting to which they subjected conquered lands both, of course, on legal grounds, since the requisitions of works of art were part of the terms of the treaties that the occupiers agreed with the occupied (although there were several cases of works being illegitimately removed), on “practical” grounds (the occupiers believed that their restorers were the most skilled and entitled to repair works in need of care), and on cultural grounds: it was said, in fact, that they were beginning to think that culture and freedom were two overlapping concepts. Clarifying France’s position had been thought of as early as 1794 by General Jacques-Luc Barbier, who, after raiding paintings in Flanders occupied by the revolutionary army, had stated that masterpieces “for too long had been sullied by the sight of servitude” and that “it is in the bosom of free peoples that the trace of famous men must remain.” And since the “homeland of the arts and genius, of liberty and holy equality” was identified in the French republic, the natural consequence of such assertions was that France, as the homeland of liberty (and consequently of all free men) could consider itself the repository of all art produced by free men. This, in short, was the ideological basis that served to justify the spoliations.

A basis without which the project of that universal museum that gives the title to the exhibition could not have seen the light of day and which was to be based in Paris, capital of the “homeland of freedom,” “modern Athens” and a city destined to hold the primacy of culture, to the detriment of a Rome that, as a papal seat, according to revolutionary ideology could not have the minimum requirements necessary to be considered a homeland of the arts. The “universal museum” was to bring together all the most significant production of the great artists of the past, so that not only connoisseurs and intellectuals could have access to art, but that the works of the geniuses of art history could be put at the service of all citizens. If, however, the means were somewhat questionable, it is necessary to recognize that, as the aforementioned Curzi points out in his essay, “in the idea of the democratization of culture, the Napoleonic experience marked a fundamentally important step, and the most valuable legacy remained precisely in the conception and cultural organization of the museum and its social role.” Of course: there was no shortage of opposing voices, the most famous of which is undoubtedly that of Quatremère de Quincy, who in his writings (particularly in his Lettres à Miranda) lashed out in fiery tones against the robberies enacted by his countrymen. “C’est une folie,” wrote Quatremère de Quincy, “de s’imaginer qu’on puisse jamais produire, par des échantillons, réunis dans un magasin, de toutes les écoles de peinture, le même effet que produisent ces écoles dans leur pays” (“It is a folly to imagine that one can produce, through examples of all the schools of painting gathered in a warehouse, the same effects that those schools produce in their countries.”) It is just a pity that the exhibition does not give an account of the opposing voices, and to remedy this shortcoming it is necessary to read the quick essay in the catalog by Sergio Guarino to whom is entrusted, among others, the task of giving an account of the opposition that the revolutionary and Napoleonic ideology encountered in France.

Which artists, however, were selected to be sent beyond the Alps? The answer to this question is up to almost every room on the second floor. The French commissioners sent to the occupied lands mainly raked up works of classical art (in the exhibition we have several copies, such as that of the Laocoon mentioned above or that of the Capitoline Venus, but also an original such as the so-called Jupiter of Otricoli from the first century B.C., which comes from the Vatican Museums) and works by artists who, from the Renaissance to modernity, reinterpreted classical taste according to their renewed sensibility. Raphael, considered “le premier peintre du monde” (we have the very famous Portrait of Pope Leo X on display), and not even the Bolognese classicists could certainly not be absent: the French accorded them a special predilection, and the corpus of Emilian works present at the Scuderie del Quirinale is undoubtedly the most substantial. Thus, boxes containing works by Correggio, Guido Reni, the Carraccis, Domenichino, Francesco Albani, and Guercino were sent to Paris: on display are examples of the highest quality for each of these artists. Particularly paradigmatic is, for example, a Compianto by Annibale Carracci much appreciated by Bellori, which is singled out by the curators as one of the historical sources chosen as a “guide” to orient themselves among the works to be sent to France. Likewise, Guido Reni’s splendid Fortuna: this figure so light and ethereal was seen as a kind of modern transposition of ancient Venuses. If the Bolognese were admired for their crystalline painting, the finesse of their drawing, and their ability to sublimate nature into ideal forms, the Venetians, on the other hand, were prized for their original and extraordinary use of color: paintings by Titian (theAssumption from Verona Cathedral), Veronese, and Tintoretto fill the walls of the fifth and final room on the second floor.

The goal of the French was, as curator Carolina Brook explains in her catalog essay, to “establish with the past a kind of aesthetic continuity”: to achieve this, the works confiscated from the clergy and aristocrats banned by the republic were not enough. It was therefore necessary to have recourse to works from the lands of conquest, most of which were to replenish the collection of the Muséum National (the Louvre), which was to become, still quoting Carolina Brook, “the privileged place of revolutionary culture, capable of coagulating within it various social functions, from training for artists, to delight for connoisseurs, to civic education for citizens, stimulated through the observation of the fine arts to a new feeling of belonging.”

|

| Head of Jupiter known as Jupiter of Otricoli (1st cent. BCE; Greek marble with late 18th-century additions in Luna marble; Rome, Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Museo Pio Clementino) |

|

| Raphael, Portrait of Leo X (1518; oil on canvas, 155.2 x 118.9 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

|

| The rooms with works by Emilian painters |

|

| Guido Reni, Fortune with a Crown (c. 1637; oil on canvas, 163 x 132 cm; Rome, Accademia Nazionale di San Luca) |

|

| Annibale Carracci, Lamentation over the Dead Christ with Saints Francis, Clare, John the Evangelist, Mary Magdalene and Angels (1585; oil on canvas, 373.8 x 239.7 cm; Parma, National Gallery) |

|

| The room with the works of the Venetian painters |

|

| Titian, Assumption of the Virgin (1530-1532; oil on canvas, 394 x 222 cm; Verona, Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta) |

Interesting to reiterate how this feeling of belonging had developed, however, even among the occupied. With the exception of the sixth room, which is avulsed from the path of the second floor (the theme is the re-evaluation of the primitives, that is, the painters “before Perugino” who were initially discarded by the art raiders: an essay in the catalog by Ilaria Miarelli Mariani focuses on the same subject), the rest of the exhibition is devoted, precisely, to what was happening on Italian soil as a result of the thefts. The thematic change is also underscored by the different color of the exhibits: an amaranth red, probably chosen to highlight the fervor with which they devoted themselves, from 1815, to recovering the works. The public picture galleries (such as the one in Bologna, the one in Brera, or the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice), which had already sprung up in the Napoleonic era to house paintings and sculptures from the buildings of suppressed religious congregations and were also set up on the model of the “universal museum,” had been conceived with the aim of gathering the best of local artistic productions, and after 1815 found themselves having to accommodate works returning from France. Closing the exhibition (and here the organizers have played the card of setting up with a strong scenic impact) is the plaster cast of Canova’s Venus italica surrounded (it makes a bit of a voyeur) by a selection of busts of illustrious artists made for the Pantheon, at the urging of Canova himself. The Venus italica, which was intended to be created as a copy of the requisitioned Venus de’ Medici, was actually an iconographic invention of Canova, who thought of it as a symbol of the nation itself and its artistic genius. The preconditions for the Risorgimento were being born: this last allusion is deferred to Francesco Hayez’s Meditation (understood as “Meditation on the History of Italy”), placed in direct dialogue with the Italic Venus.

|

| The rooms on the second floor |

|

| Last room with Venus Ital ica and busts of the illustrious artists |

|

| Antonio Canova, Venus Ital ica (1809-1811; plaster, 72 x 52 x 55 cm; Possagno, Gipsoteca Canoviana) |

|

| Francesco Hayez, Meditation (1851; oil on canvas, 92.3 x 71.5 cm; Verona, Galleria d’Arte Moderna Achille Forti) |

One goes out to admire the view of Rome from the top of the Quirinale with the impression that one has witnessed an exhibition that unravels between highs and lows (one of the highs, it should be pointed out, are the panels bearing the dates and route of all re-entries), divided sharply into two sections, one (the first) easier to read, the other a bit more chaotic and slightly disorienting (as the rooms devoted to the birth of picture galleries mingle with those devoted to art as cultural identity in a less than linear succession): nevertheless, it cannot be denied that The Universal Museum. From Napoleon to Canova is a quality exhibition, and the intent to set up a review on a fragment of our history that is as well known as it is actually little explored, because it has always been covered by the clouds of nationalist rhetoric: the reading offered by the exhibition is undoubtedly as unbiased as could be expected and induces us to reflect not so much on thegreed with which the French preyed on Italian territory, but if anything on the fact that (paradoxically) it was in the context of Napoleonic plundering that the modern idea of the museum developed. The revolutionaries’ idea was certainly particularly utopian, but it served as a basis for future reflections on the usability of art-these are assumptions that emerge clearly from the exhibition. The catalog is a useful tool for further study: of the most interesting essays we have already mentioned, so we will simply state that there are no obstacles to considering the catalog as a fundamental contribution offered to studies on this brief but convulsive period of art history.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.