Pisa is home to theonly public work in Italy by Keith Haring (Reading, 1958 - New York, 1990) designed to remain permanent, as well as the last of his career: Tuttomondo, the mural that the American considered among the artists to whom we owe the birth of street art created in 1989 on one of the walls of the convent attached to the church of Sant’Antonio Abate. Pure coincidence is due to the presence in the Tuscan city of the large work characterized by the artist’s iconic colorful and tangled figures: two years earlier Keith Haring met a Pisan student, Piergiorgio Castellani, in New York and the two became friends; when the American visited his friend in Pisa, the idea was born in both of them to create a work that would remain forever visible precisely in the Tuscan city. The project, unique in Italy, attracted many citizens of all ages and resulted in the large 180-square-meter mural that everyone can still admire today. What more suitable city then than Pisa to host a major retrospective dedicated to Keith Haring’s short but important career? Until April 17, 2022, in fact, Palazzo Blu presents in its exhibition halls the exhibition with the concise title Keith Haring, which, however, echoes in the ears and minds of the general public, certainly attracting many visitors because of the importance of the great name, among the leading artists and writers of the second half of the twentieth century. Curated by Kaoru Yanase, Chief Curator of the Nakamura Keith Haring Collection, and produced by the Pisa Foundation in collaboration with MondoMostre, the exhibition enjoys the extraordinary participation of the Nakamura Keith Haring Collection, the personal collection that Haring-loving entrepreneur Kazuo Nakamura began to assemble in 1987 and is housed in the museum dedicated to the artist in Japan. Thus, more than one hundred and seventy works from the significant collection have been brought together for the first time in Europe for the Pisa exhibition.

If the intent of the exhibition is solely to retrace in its main stages the short life of Keith Haring, who died in 1990 at the young age of thirty-one in Greenwich Village from complications related to AIDS, the retrospective gives the visitor a complete overview of the famous writer’s artistic activity, from hisbeginnings to his last series of drawings (The Blueprint Draw ings), which he made a month before his death. Through the nine sections of which the exhibition is composed, the public is in fact given a smattering, en passant and without any particular depth, of the themes and different expressive techniques he used throughout his production, from painting to drawing, from public and commercial art to murals and sculpture.

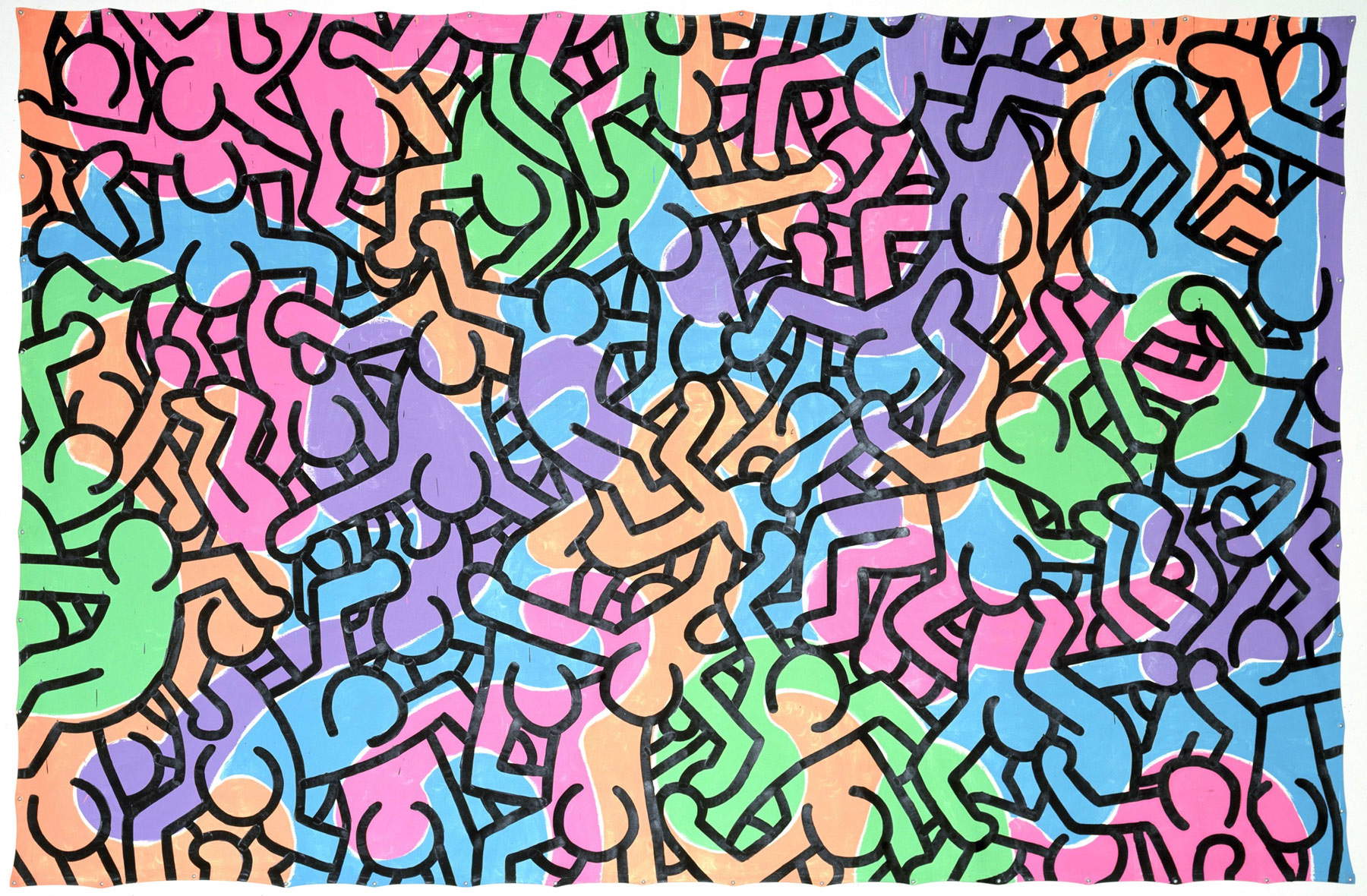

The works in the exhibition are mostly lithographs and silkscreens on paper, with the exception of a few cases, if you don’t count the painted aluminum sculptures: Untitled (People), a large acrylic on muslin from 1985 on which Keith Haring’s little men with marked outlines are entangled amidst ringing colors; Untitled (Medusa), the artist’s largest print made in 1986 depicting the mythological creature with a head full of snakes that Haring reinterprets with seven long necks entangled and to whose ends bodies are attached; 1986’s Untitled , an acrylic on canvas that harks back to Picasso’s primitivism andAfrican art, with which the artist shares the idea of giving form to the power of fear, much like the sculptures of African tribes that take on a role as protective talismans against the invisible powers that surround humans; and 1984’s Secret pastures , also an acrylic on canvas.

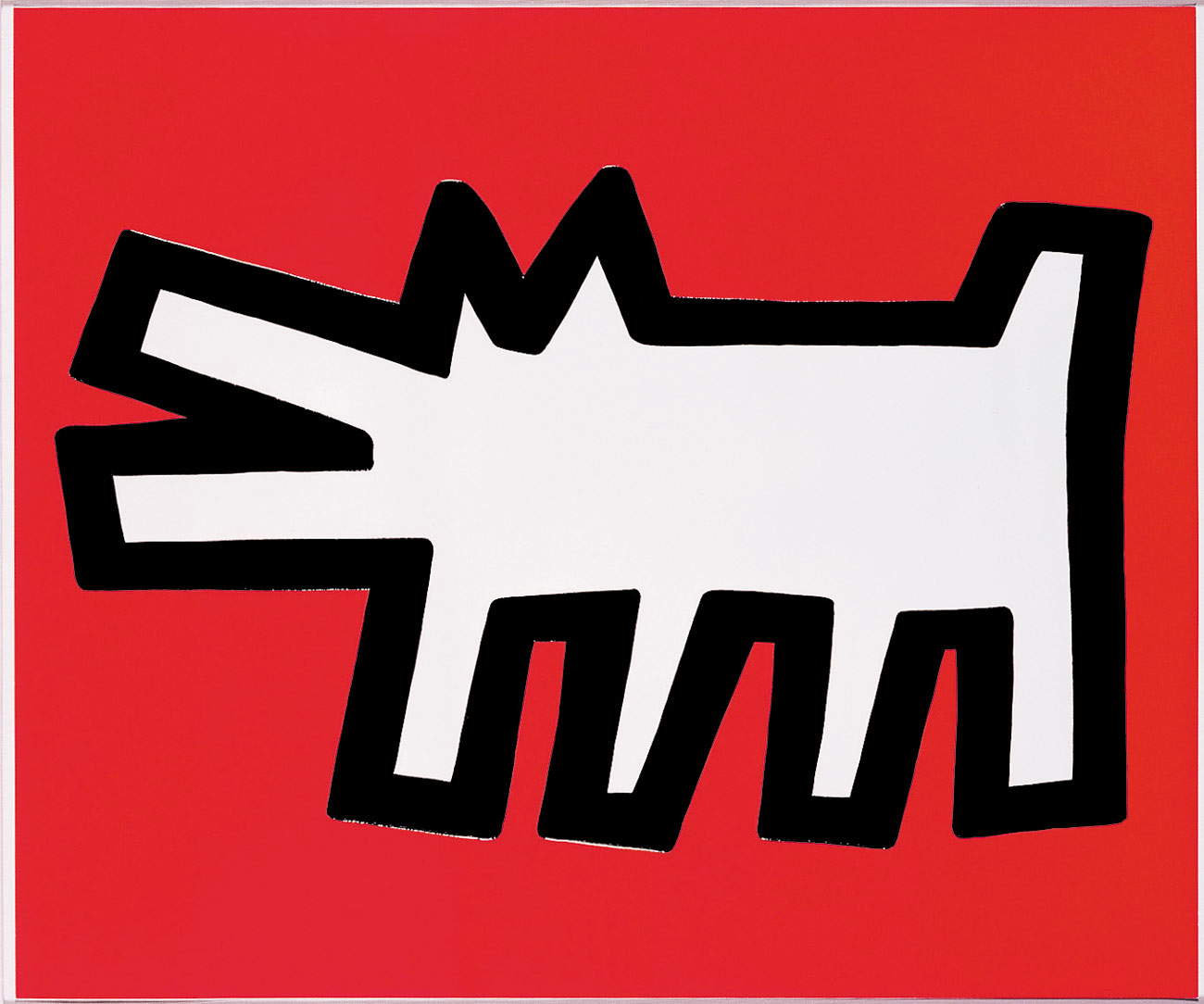

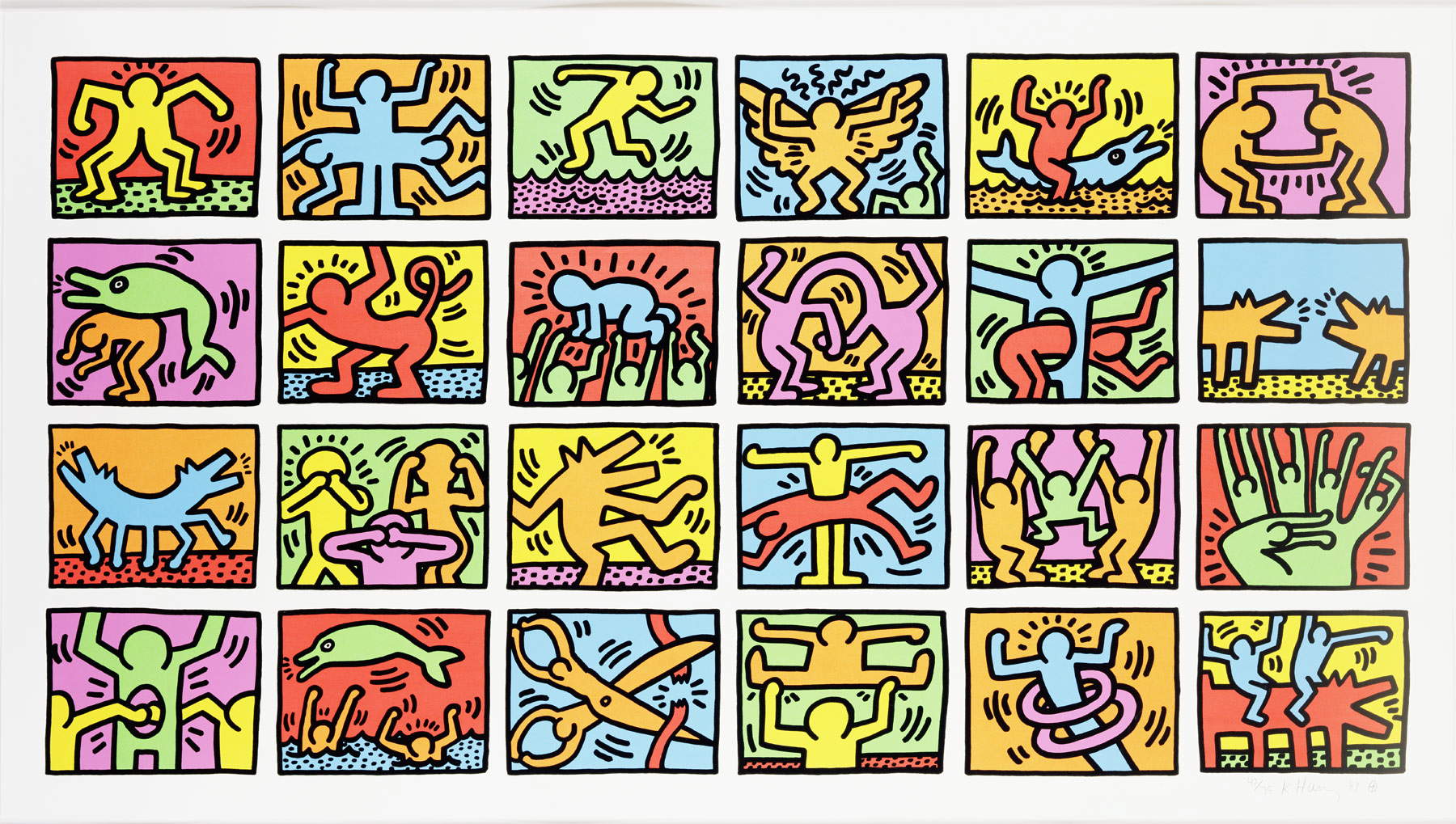

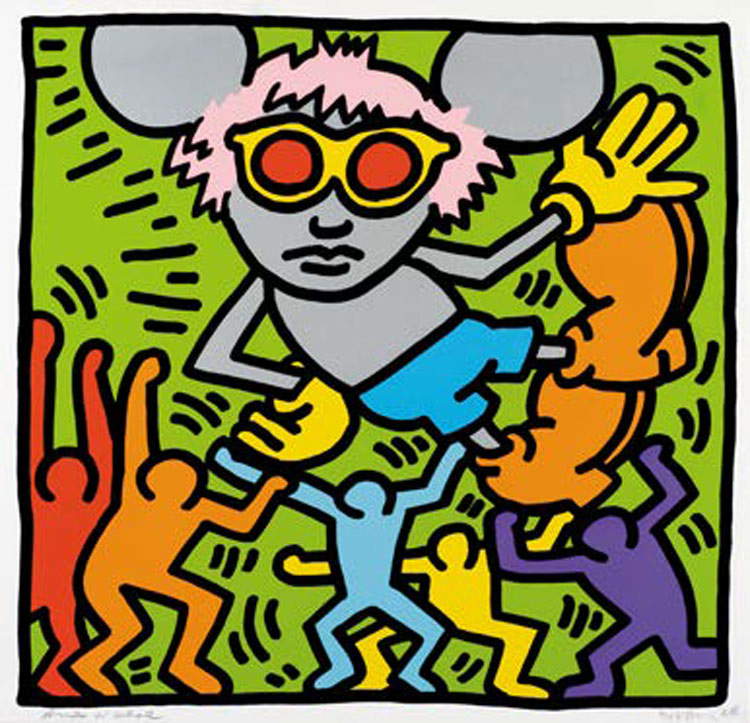

Above all, however, the retrospective has on its side the fact that it has brought to Pisa lesser-known and more widespread works that go beyond the iconic symbols created by Haring himself and that today can be seen as the predecessors of emoji, such as the smiley faces, the radiant child, the angel, the barking dog, the dancing figures, and the three-eyed face, through which he addresses important themes such as life, love, and death. The most “iconic” of the exhibition rooms is the one that brings together the Icons series, published in 1990, which includes his most typical characters: the radiant child represents innocence, purity, Haring’s own alter ego; the barking dog often indicates suspicion and if depicted in a standing position can represent authoritarian government, abuse of power, oppressive regime; theangel refers to the presence of spiritual creatures or guardians of human beings but also to the complexity of life, power and chaos, and if it has an X on its chest it may be a sacred symbol or may allude to mating; finally, the three-eyed face is often associated with greed and excess. In the same room is the aforementioned Untitled (People), the 1989 Retrospect series consisting of twenty-four images from Keith Haring’s Pop Shop series, of which each can be seen as a precise moment in his life, always in motion, and the series Andy Mouse (1986), a synthesis of Mickey Mouse, Walt Disney’s character always loved by Haring, and Andy Warhol, his friend and one of the leading exponents of pop art, in which Andy Mouse with dollar bills become an ironic representation of capitalist society and ultimately America.

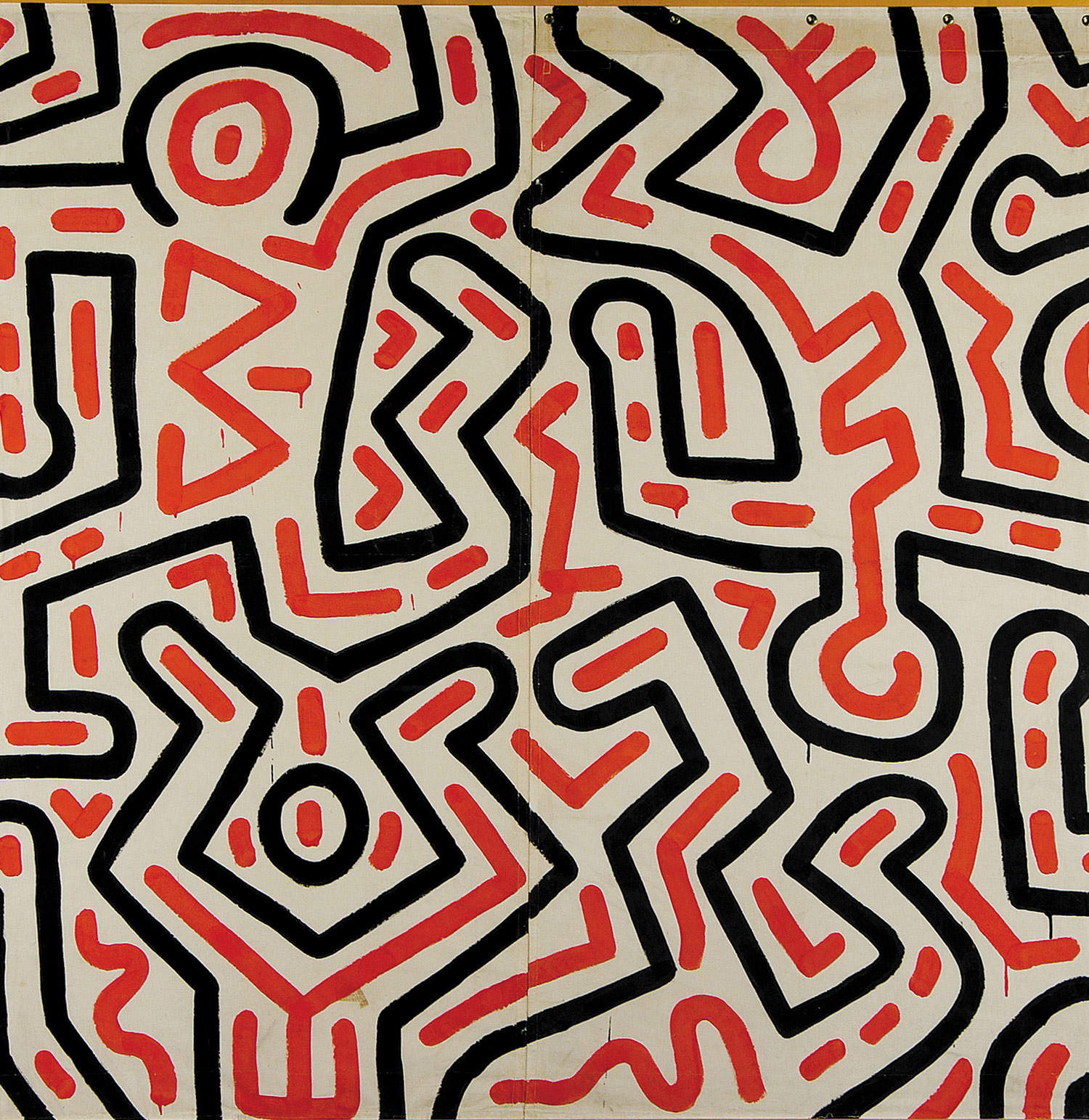

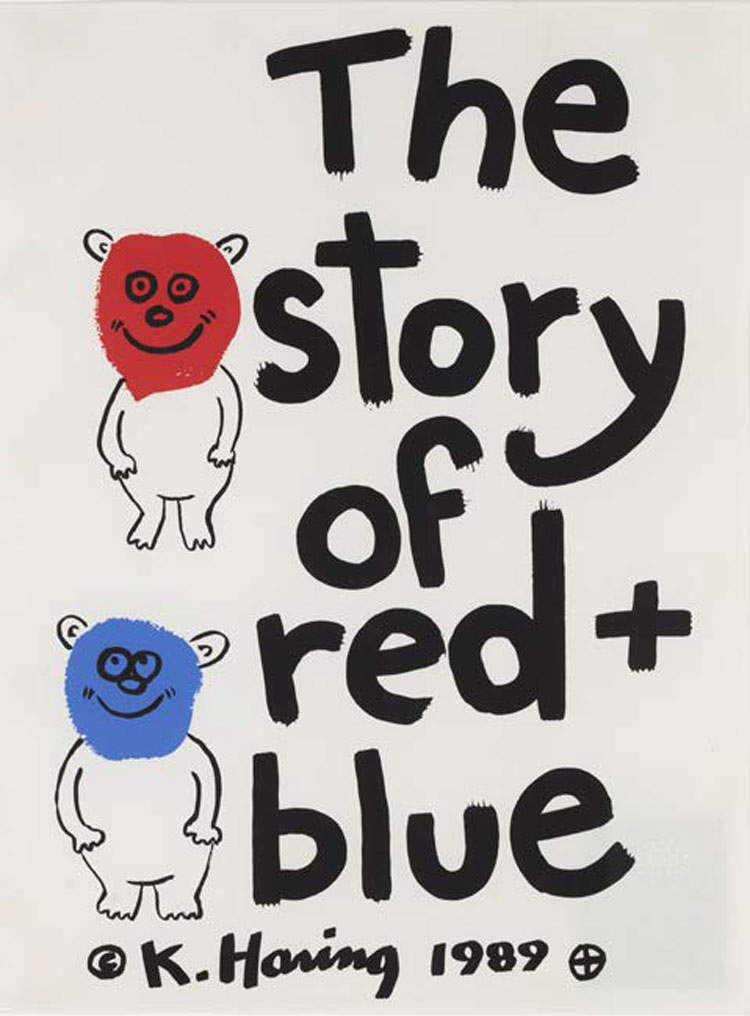

Beyond these icons of his, we said, the exhibition presents the public with lesser-known series, such as The Story of Red and Blue, made especially for children in 1989: Haring paints red and blue shapes around which he then builds with black lines figures and objects of all kinds, such as animals, portraits of people, cars, baby toys and so on. Each image gives the viewer the opportunity to invent his or her own story, or even better using all of them; in fact, it is no coincidence that many schools and museums in the United States have introduced this particular series into their educational programs. Throughout his existence Keith Haring worked with children of all ages and backgrounds, published various books for them, and initiated various projects involving them. It is the radiant, crawling child who never stops that is one of his universal symbols: it releases rays of power, possesses infinite energy, defies all danger; it is a pure message of joy.

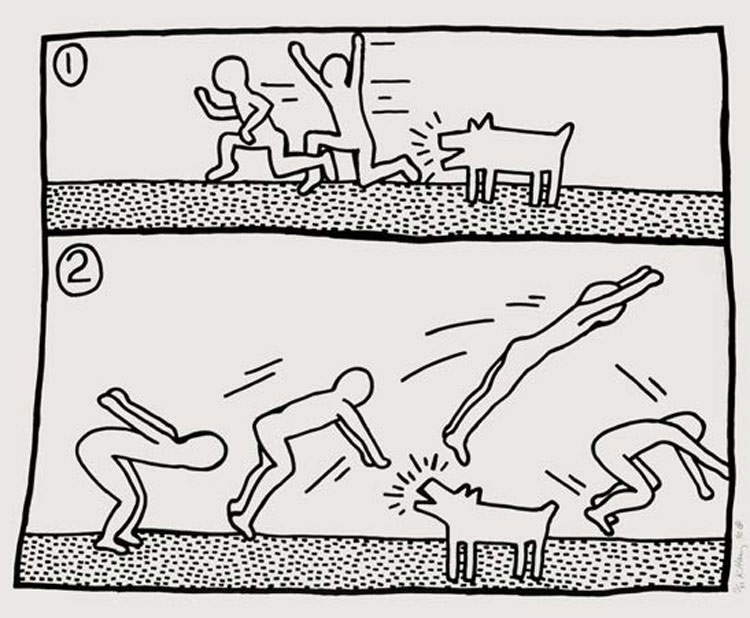

Then there is Apocalypse, which Keith Haring completed in collaboration with William S. Boroughs, an important exponent of the Beat Generation, a movement that developed in the United States in the 1950s against capitalism and power and was based on freedom of expression in all literary and artistic fields. It consists of ten prose pieces composed by Boroughs on the theme of chaos destroying the world; Haring interprets the writer’s texts through illustrations: each image is a collage in which advertisements, references to famous works of art (including the Mona Lisa) and references to Catholic theology are combined. The series is created after the artist discovers that he is HIV positive, after he is diagnosed with AIDS, and lives with it. From this point on, themes such as fear or political messages related to AIDS and drugs become much more frequent, and Apocalypse offers the audience just a first demonstration of thepersonal hell he is experiencing. And finally, interesting are the seventeen drawings with which the retrospective closes (and also his artistic activity, since the artist made them just a month before his death). They are images that summarize, sometimes with comic strips, his most typical symbols and figures combined in surreal scenes: dogs, crawling children, snakes, pyramids, flying saucers, extraterrestrials, through which the dark sides of society are addressed and where the male sexual organ often becomes the protagonist. Three series that are unknown to most and that the Pisan exhibition gives the opportunity to get to know.

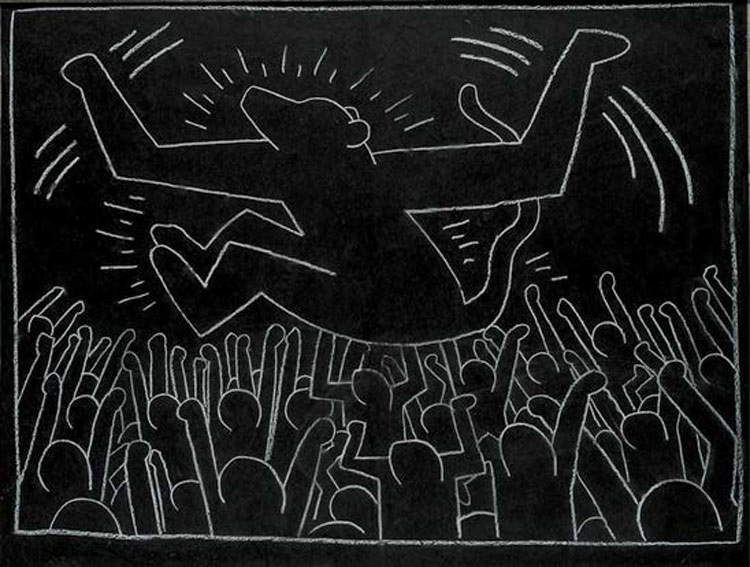

The themes of his art follow one another room after room, in a set-up that becomes at times evocative and immersive, such as the first exhibition room that catapults the visitor into the tunnel of a New York subway, amid neon lights and graffiti made with white chalk on the layer of black paper covering unused advertising panels: this is in fact the context in which Keith Haring’s drawings first appeared in the 1980s. Works that become part of the Untitled (Subway Drawing) series. His intention is to create art that is accessible to all, in busy public spaces that are easily accessible. “My hope is that one day, kids who spend their time on the street will get used to being surrounded by art and that they can feel comfortable if they go to a museum,” he said. He did not want to define the art he created because it meant “destroying its purpose”; “Art has no meaning because it has many, it has infinite meanings.” He expresses universal concepts such as birth, death, love, sex, and war through his world of radiant children, animals, and faceless figures because they are universal.

In the 1980s black light is the usual light inside clubs: so he begins to use fluorescent colors that glow and seem to come out of surfaces; he is interested in seeing what psychedelic effects can be created from his images. These are dancing figures, flying saucers hitting pyramids, bodies that refer to fertility with pregnant figures.

Photographs and posters recount the Pisan adventure of creating Tuttomondo, which opened in June 1989. Some works then draw inspiration from Aztec, African and African American art, with pyramids, totems, masks, body painting, to represent mysterious powers and mythological symbols. An entire section is then devoted to music: his poster images dealing with important issues such as AIDS prevention, gay rights, apartheid, racism, war, violence, and many others are often used to publicize musical events and concerts. He also collaborates with musicians and singers to create covers for music albums: one example is the cover for David Bowie’s Without you, which depicts two figures joined in an embrace.

The audience thus has the opportunity to retrace in its milestones and most significant themes the life and art of the U.S. artist who, starting from New York subway stations, achieved worldwide fame, giving birth to urban art and street art. A universal art, understandable and accessible to all. Not very useful, however, is the catalog that accompanies the exhibition, which re-proposes the tour but with cuts (such as the Apocalypse series that has been drastically summarized) and without the addition of in-depth texts or essays, except for a contribution by the curator. Exhibition therefore promoted, but with some reservations.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.