Browsing through the ever-expanding bibliography devoted to Antonio Ligabue, it will not be uncommon to come across comparisons with Vincent van Gogh, a painter with whom Ligabue shared part of the personal story (both experienced loneliness, marginalization, and poverty) and several traits of artistic personality: both lived painting first and foremost as a necessity, both entrusted to the power of the paintbrush the powerful, lofty and visionary expression of what they evidently could not or did not express by other means, both felt, with concrete awareness, their condition as artists, an awareness that in Van Gogh was manifested through the lucid theory poured into the many letters written to friends and family, and in Ligabue through the idea that, in a not even too distant tomorrow, the originality of his language would be able to reach the widest possible audience. In the catalog of the commendable exhibition Antonio Ligabue. L’ora senz’ombra, which the BPER Banca Gallery in Modena set up with the knowledge that long and troubled was, and still is, the path toward Ligabue’s recognition, an article that Grazia Livi signed for Epoca in March 1961, on the aftermath of the exhibition held at the Galleria La Barcaccia in Rome (it was the first opportunity to make Ligabue’s inspiration known outside the Emilian lowlands), has been recovered: the talented journalist perhaps first spoke of Ligabue as the “Van Gogh with the red motorcycle.” Although we move into the terrain of hyperbole, the reference to the Dutch painter is perhaps more fitting than the undoubted exaggeration might make it appear.

It is all a matter of correct placements. For years, Ligabue has been saddled with the label of naïf, and there are those who still insist on considering him a “naïf painter,” despite the fact that the most astute critics have long since resolved this prejudice that still surrounds the figure of Ligabue (a “violence,” as Ezio Aldoni and Giuseppe Caleffi, authors of one of the most interesting and informed biographies of the artist), the result of choices and juxtapositions of yesteryear, which nevertheless pertained more to the logic of commerce than to that of art. To render the idea, it will be useful to return to an article that Giancarlo Marmori published in 1974 in L’espresso, dedicated to the explosion of the naïf fashion: “The vogue for naïf, puerile or crazy, true or false as it may be,” Marmori wrote, “has broken the banks of elite amateurism to burst in everywhere. In fact, for some years there have been turbs of naïfs and their consumers, everywhere in the world. There are some in capitalist and communist Europe, in the two Americas and Japan, in Haiti and the Lower Po Valley. So that, as if part of humanity had been seized by infantile regression or schizophrenia, this strange figuration has ended up imposing itself in countless areas.” Marmori also wondered why it was so successful: “on the one hand, one can venture that the praise of the instinctive and of madness is an essential carryover of the anti-culture of today and yesterday, on the other hand, it should be remembered that these aesthetic products turn out to be easy to read, sometimes pleasant.” It was a fashion that raged to the point that many galleries dedicated to naïf sprang up, there were events and fairs dedicated to this type of painting and sculpture, and a number of dedicated museums also sprang up. Ligabue was considered, along with Henri Rousseau, to be a kind of progenitor of the genre, a source of inspiration for hordes of sincere or interested imitators, and he also turned out to be the most expensive.

One is perhaps not too far from the truth in believing that the silence of much of the criticism on Ligabue is due to the fact that this fashion saw him as a protagonist in spite of himself, and for a long time he was considered more a matter for the history of costume (or at most for the history of taste) than for the history of art. An artist moved by a sincere passion and inner need and yet exploited, willy-nilly, for reasons that had nothing to do with his art. A troubled personal history also conveyed to convey the cliché of the mad yet brilliant artist. And it certainly did not help too many exhibitions set up, even recently, more to pander to the preferences of the public, which has never abandoned its interest in Ligabue’s art, than to critically and philologically order his art, and to find it an appropriate collocation. Perhaps, however, a reversal is discernible. With the naïf fad dead and buried, with a critical debate that in recent years has dealt more appropriately with the art of so-called outsiders, with a history of Ligabue studies within which it is now possible to establish fixed points, the time is ripe to begin to consider an adequate critical recognition for Ligabue’s production. Of course, important pieces are still missing: for example, few major museums have works by Ligabue. Except for the collection of the Ligabue Foundation in Gualtieri, the most substantial nuclei are those found in the rooms of the Labirinto della Masone in Parma, the Magi ’900 Museum in Pieve di Cento, and, indeed, in the collection of the BPER Banca Gallery in Modena. This is still too little: important as they are, they are all private collections or originate from private collections, and they are all located in the region where Ligabue worked. However, there has been no shortage of important study opportunities.

One of the merits of the BPER Banca Gallery exhibition, which moreover picks up on some of the themes and motifs of the recent exhibition at the Reggia di Monza, lies in the fact that the curator, Sandro Parmiggiani, has imagined a review capable of building on what has been produced so far on Ligabue in order to set a sort of milestone. Modena, rather than a point of arrival, is a point of departure. Of the series: we take the critical contributions that have best defined the figure of Antonio Ligabue, and we start from there. This also explains the title of the BPER Gallery exhibition: “shadowless hour,” the title of a novel by Argentine writer Osvaldo Soriano, aims to convey the idea of the sun that, in the midday sky, cancels all shadows. The hour when, Parmiggiani writes, “authentic deep truths come to the surface.” Among the milestones, it is necessary to record the opinion of one of the finest art critics of the second half of the twentieth century, Roberto Tassi, who in 1975, as the fashion for naïf was spreading, recalled that, looking at Ligabue’s paintings, this definition would have to be abandoned: "what naïf,“ he wondered, ”would know how to give us such precise, subtle drawings of snappy line, of learned line? What naïf would know how to etch such expressive and refined etchings or model clay with such skill?" It might seem paradoxical that, in order to go in search of interesting and disinterested opinions on Ligabue, it is necessary to peruse literature, from Cesare Zavattini to Attilio Bertolucci, from Giancarlo Vigorelli to Renato Martinoni. Evidently, the immediacy of Ligabue’s art was able to reach first and best those who do not deal with art by trade and are therefore naturally less circumspect, but no less able to grasp the originality of a language that expresses itself through images: many who have dealt with letters have been able to write memorable pages on the figurative arts. Nor was there any lack of appreciation from other artists, above all from Maurizio Cattelan, mentioned by Parmiggiani in that sort of brief anthology on Ligabue that is the first of his two essays in the exhibition catalog: a sign that those who share Ligabue’s sensibility have no difficulty in recognizing the value and originality of his work.

The exhibition is constructed with the usual minimalist slant that characterizes BPER Gallery’s reviews, but in that concentration of twenty-one works that makes up the exhibition itinerary, arranged along the deserving open layout by young architect Andrea Isola, a substantial fragment of Ligabue’s soul is contained. The iteration of the exhibition unfolds chronologically and covers the entire known span of Ligabue’s career, beginning with a 1929 work, Caccia grossa, thus executed when the artist was only 30 years old: beyond the rare, probably unique, self-portrait in the guise of an explorer that Ligabue includes in the composition, it is noteworthy how stroke and color are still far from becoming violent, scratchy, textural as they will be in the much more celebrated works of the mature Ligabue. The flat, muted backgrounds, the stylized line and the almost fairy-tale-like atmosphere are reminiscent, if anything, of the paintings of that Henri Rousseau to whom Ligabue has often been compared because of proximity of theme and similarity of experience. And by immediately displaying this work at the opening, the exhibition poses one of the most fascinating questions about Ligabue’s art: was his alleged ignorance really such? Was Ligabue really ignorant of painting, and was everything he spilled on his works seriously moved solely by what the artist had inside? Could it be that he had never seen a painting, even only reproduced in a book, could it be that he did not know the production of those who had preceded him? Parmiggiani addresses this node as well, recalling a passage from the aforementioned Bertolucci, when he wrote that Ligabue was a painter “also capable, from who knows what distant cultural imprests, of a visionary but real painting to the point of exhaustion.”

Moreover, in the very article by Grazia Livi, Ligabue, whom she interviewed, declared that he knew Rousseau well, although he did not appreciate him as he found him “too childish.” It might therefore be natural to consider the Doganiere an early point of reference for a painter who harbored the same passion for exotic animals and could not count on many other exemplars who had tackled the same subject. Certainly, Ligabue must have seen ferocious animals, such as the lions and tigers that constitute one of the most constant in his work, in some circus (such as the one depicted in a powerful painting from 1941-1942, in which we see two tamers, one intent on making a lion jump through a hoop, and the other putting his mouth inside the beast’s jaws) or at the St. Gallen Zoo in Switzerland, where he spent the early part of his life, but the proximity of these early paintings to Rousseau’s experiences is such that it suggests that he somehow retained the memory of some painting by the Frenchman. And even looking at the same circus-themed painting, with the shadows of the bars of the cage creating a geometric pattern on the runway and causing our attention to converge on the fulcrum of the scene, one cannot help but notice how this expedient presupposes some form of meditation on the composition and the attitude to be taken toward the subject matter: Ligabue’s painting, in essence, is much less instinctive than one might think.

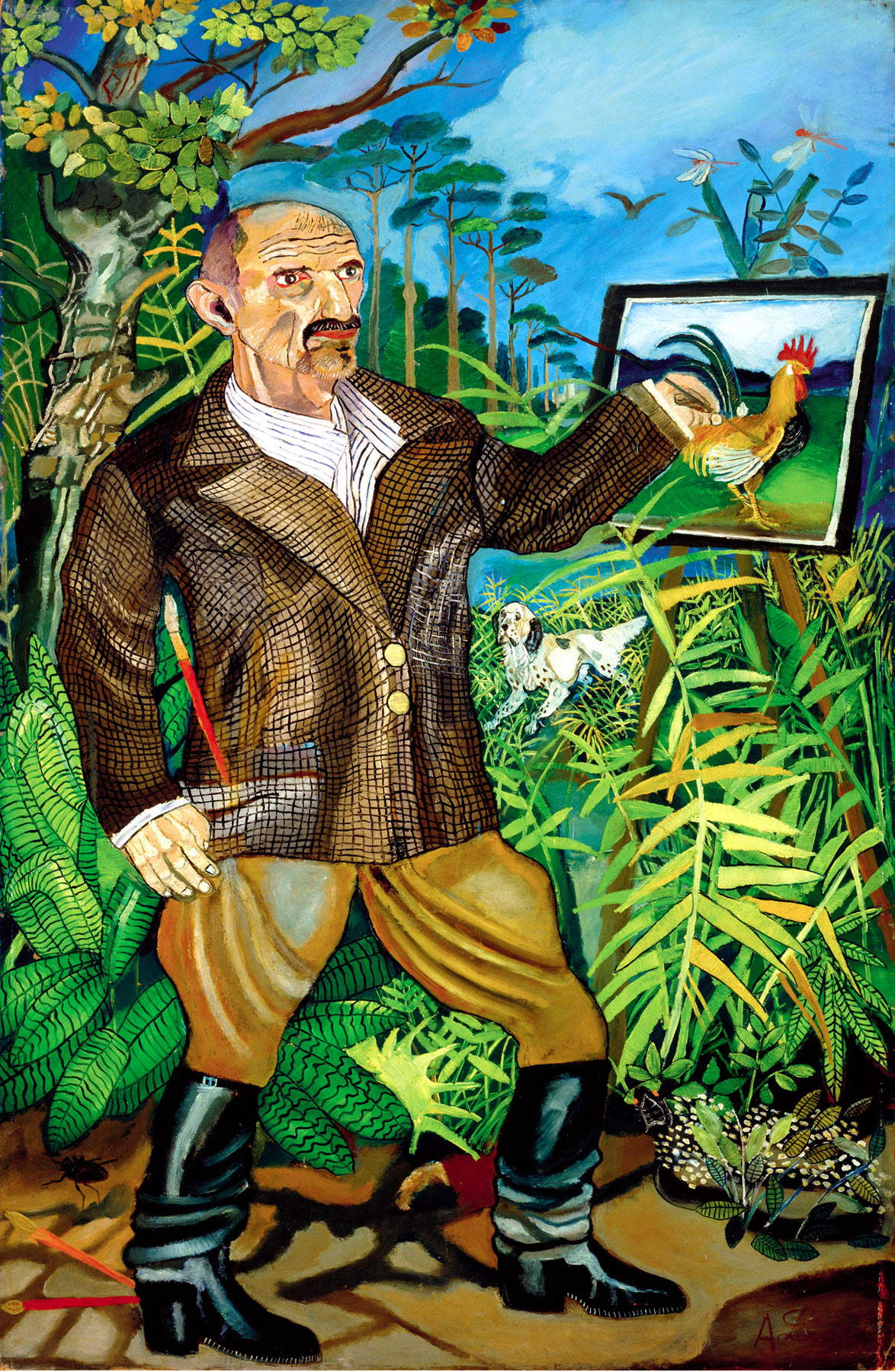

It is difficult then to believe that the mania for self-portraiture was completely autonomous and that having observed Van Gogh’s self-portraits did not have some influence on this obsessive inclination: already Tassi thought it plausible that Rousseau and Van Gogh were the artists who most inspired Ligabue. The Modena exhibition aligns as many as four self-portraits, from 1940 until the late 1950s, respecting the proportions that this significant strand takes within Ligabue’s production: more than one hundred and seventy out of about nine hundred archived paintings. In one of these paintings, the artist depicts himself with a few flies tormenting his face, a typical presence in his self-portraits and an allusion to his torment, and in others, such as theSelf-portrait of 1956-1957 or the large-format one, Self-portrait with easel of 1954-1955, belonging to the collection of BPER Banca and where he portrays himself full-length, intent on painting the image of a rooster, the emphasis is on the idyllic nature in which the painter is immersed, making clear the contrast between the world he longed for, the world he felt closest to, the world he most felt as welcoming and familiar, namely that of the fields, woods and animals, and his condition as an individual trapped in his suffering existential isolation.

Then there is no shortage of bucolic landscapes, which always retain a trace of the childhood he spent in Switzerland: in the two paintings ofPlowing with Oxen by BPER we can see in the distance the steeple bell towers typical of churches in the German area, the same ones we see, surrounded by their villages, in Landscape with Animals from a private collection or again in Return from the Fields with Castle by BPER. Observing these saturated colors, these uniform backgrounds, these lines so simple but robust, this ability to transfigure nature into visions that have more to do with memory than with the view from life, it is hard not to think of the alpine landscapes of Ferdinand Hodler, a painter well represented at the Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, and what is more, with landscapes of the hues that would later return in Ligabue: the possibility that Ligabue, who had visited the museum in St. Gallen as a boy, must have received a strong impression from the landscapes of Hodler, a key painter in the sphere of that expressionism to which Ligabue’s art often tends to be juxtaposed, has perhaps not yet been considered. Juxtapositions that, although also fitting for landscapes, were mostly inspired by the paintings with animal fights, which can also be admired in the Modena exhibition, starting with the Lioness with zebra or the Fleeing Fox (“He caught the stealthy red fox between the terror of death and the amazement of the timeless sunset,” Zavattini wrote, probably having this painting in mind). Animals with which Ligabue identified, as much in the domestic ones, which animate tranquil scenes of rural life, as in the ferocious ones, which in their furious battles reveal to the observer the violence, expressed on canvas, with which the artist responded to his own condition. Ligabue, wrote Maurizio Calvesi in an article published in Corriere della Sera in 1977, "made his choices in the expressionist vein, and in particular from Van Gogh. In this sense he has a definite merit, that of having deviated at least in part from the example of the great Henri Rousseau, the Doganer, godfather of naïveté. [...] Ligabue has instead clung to a reality and avoided choosing evasion. His lions are not the inhabitants of a distant world, but the haunting personifications of a roaring energy, personifications of the earth, the same earth in which his feet are planted, with the trees and the spade."

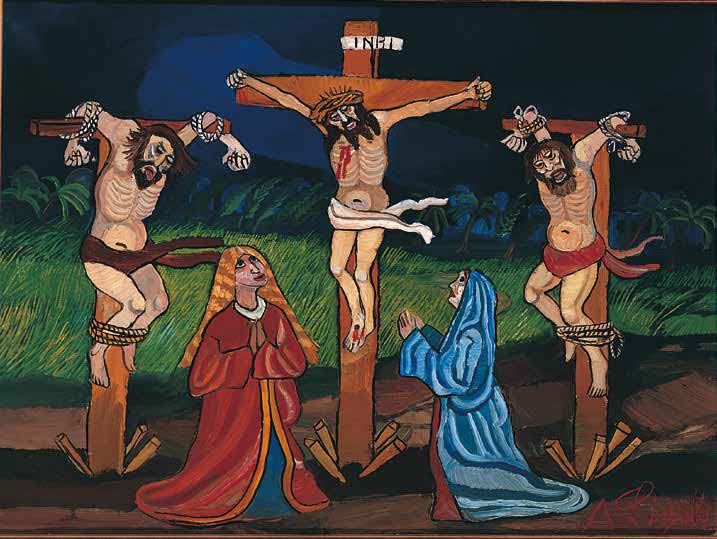

The same reasoning could be made, finally, for a Crucifixion with which the exhibition concludes, although the exhibition itinerary is organized in such a way that the public can decide for itself whether to follow a chronological iteration or to proceed thematically: a rare image in Ligabue’s production, and exhibited alongside an engraving on the same iconographic subject (the fact that Ligabue had started a small graphic production is also a sign of his awareness of his means), is a striking expressionist translation of Grünewald’s Isenheim Altar Crucifixion, and stands as a further attestation of Ligabue’s culture, an aspect of his art that has been focused on for not long and will need to be further analyzed in the future.

Another key element that finally emerges from the exhibition is the study of Ligabue’s works in relation to his psychiatric history: in fact, November 2018 marked the 60th anniversary of the last of the three hospitalizations that the painter underwent at the former San Lazzaro psychiatric hospital in Reggio Emilia, and as a result it was possible to disclose his medical records. The exhibition catalog collects and publishes them, also benefiting from the point of view of psychiatrist Domenico Nano, chief emeritus of psychiatry at the Department of Mental Health at the Novara ASL. What emerges is a portrait of a man for whom art was not only a means of redemption but also “a possibility of communicating,” Nano writes, “in a language that is both tragic and very sweet, in the universal language of art, fear, despair, anger, weeping, anguish, invocation, and hope.” In light of the material that has been available for a few years, the reading of the animal paintings as a “struggle for survival” such as was was that of his life, that of a man “besieged and bitten,” Nano continues, “by ancestral terrors, by a world of violence and marginalization that rejected a madman and a stranger, who was able to give us stories of animals that become universal and that impose themselves on our gaze with close-ups that assault us, catapulting us into his (our) existential drama.”

Who, then, was Antonio Ligabue? How is it possible to situate his experience? What are the elements of novelty, of originality, such as to clamor for a place in art history? Having eliminated all legacies of the past, the Modena exhibition aims to reaffirm Ligabue’s place in the groove of expressionism: Parmiggiani, in particular, having in the past coined the phrase “tragic expressionist” for him (on the occasion of an exhibition held in 2005 in Reggio Emilia and Gualtieri, curated by him and Sergio Negri, who is responsible for cataloguing Ligabue’s work), intends to emphasize with this further exhibition occasion the definition that in his opinion best fits Antonio Ligabue. It will be necessary, however, to add a further food for thought: for some time now, comparisons have taken to be made between Ligabue and Giorgio Morandi, an artist who had known Ligabue’s art and appreciated it (so we read in Aldoni and Caleffi, and in several other biographical reconnaissances). Morandi, subject to the obvious differences, had in common with Ligabue the stature of a great isolated artist and, as Vittorio Sgarbi has noted, the fact that he devoted all his art to the narrative of his own life. If Lionello Venturi’s postulate is true, who in 1957, presenting an exhibition of Giorgio Morandi in New York, asserted that the secret of his art, “its charm, its uniqueness, its greatness” lies above all in “discovering the most refined subtleties of modern art rooted in the most modest and traditional way of feeling,” for Ligabue, one could imagine that his way of feeling, also modest and traditional, was the conscious medium for expressing a disorder that needed to find some form of order, for shaping the truth of a tragedy by offering everyone the chance to explore it.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.