The masterpieces of the Torlonia Collection, the largest private collection of ancient sculpture preserved to the present day, assembled by the Torlonia princes during the 19th century in Rome, are unveiled in a series of exhibitions-events. The Louvre is hosting, from June 26 to Nov. 11, 2024, the first exhibition of Torlonia marbles outside Italy, with a display inside the newly restored summer apartments of Anne of Austria, home to the permanent collections of ancient sculpture since the Louvre Museum’s inception in the 18th century. The exhibition, titled Masterpieces from the Torlonia Collection and curated by Cécile Giroire and Martin Szewczyk, aims to highlight some of the masterpieces of ancient sculpture and invites visitors to admire the undisputed jewels of Roman art, but also to discover the beginnings of the history of museums in Enlightenment and 19th century Europe.

Sprung from the passion for ancient art of the Torlonia princes, heirs to the aristocratic practices of papal Rome, the Torlonia collection aspired, particularly with the opening of the Torlonia Museum in the 1870s, to rival the great public museums: the Vatican Museums, the Capitoline Museums and the Louvre Museum. Since 2020, the collection has been the subject of a series of exhibitions-events that offer the public a chance to rediscover, after a long eclipse, the exceptional collection of sculpture in the museum established by Alessandro Torlonia in 1876 and closed in the mid-20th century.

The two stages of the exhibition, in Rome and Milan, under the curatorship of Salvatore Settis and Carlo Gasparri with the high supervision of the Special Superintendence of Rome, reconstructed the history of the collection backwards. The Paris exhibition, on the other hand, stems from the desire to present to the public, in a place charged with history, this little-known collection in France and invites an aesthetic and archaeological journey among its works, establishing a dialogue with the Louvre collections.

The presentation to the public of a collection of ancient sculpture of the highest artistic level, accessible confidentially until recently, in a space traditionally devoted to the exhibition of sculpture since the early days of the Louvre Museum, and therefore with a significance of ’importance in the history of museums, thus constitutes a triple event in 2024.

Articulated around masterpieces from the Torlonia collection, the exhibition also aims to reveal the emblematic genres of Roman sculpture, as well as the heterogeneity of its themes and stylistic formulas. Portraits, funerary sculptures, copies of famous Greek originals, works inspired by Greek models from the Archaic and Classical periods: figures of the Dionysian thiasos and allegories reveal a repertoire of images and forms that are the strength of Roman art while establishing a dialogue between two sister collections, the sculptures of the Louvre and those of the Torlonia Museum, from the point of view of the history of the collections.

At the center of the exhibition is the history of the collection once displayed at the Torlonia Museum, and the special characteristics dictated by the circumstances of its origin. Consisting of marbles found underground in Rome, the epicenter of power and artistic production in the Roman West, or its immediate surroundings, the collection brings together sculptures pertaining to cultured art, of high quality of execution. It also includes works from older collections, unearthed since the 15th or 16th century, and, because of their long history, transformed and adapted to the taste of the time. The specificity of the Torlonia collection, at once the last princely collection in Rome and a museum turned to the future, is represented by an extraordinary work, which enjoyed great notoriety as early as the 18th century: the Caprone restored by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

A treasure chest of masterpieces of Roman sculpture, the Torlonia Museum, founded according to the principle of critical selection and scientific arrangement of the collections, preserves the centuries-old imprint of the collector’s affair. The origins of the collection led Alexander Torlonia, in the second half of the 19th century, to make it a museum open to small groups of visitors. Distancing itself from old-fashioned collecting, Alessandro Torlonia’s museum remains profoundly influenced by it, the result of the meeting of two historical dynamics: the aristocratic passion for antiquities, on the one hand, and the birth of the discipline of archaeology, on the other.

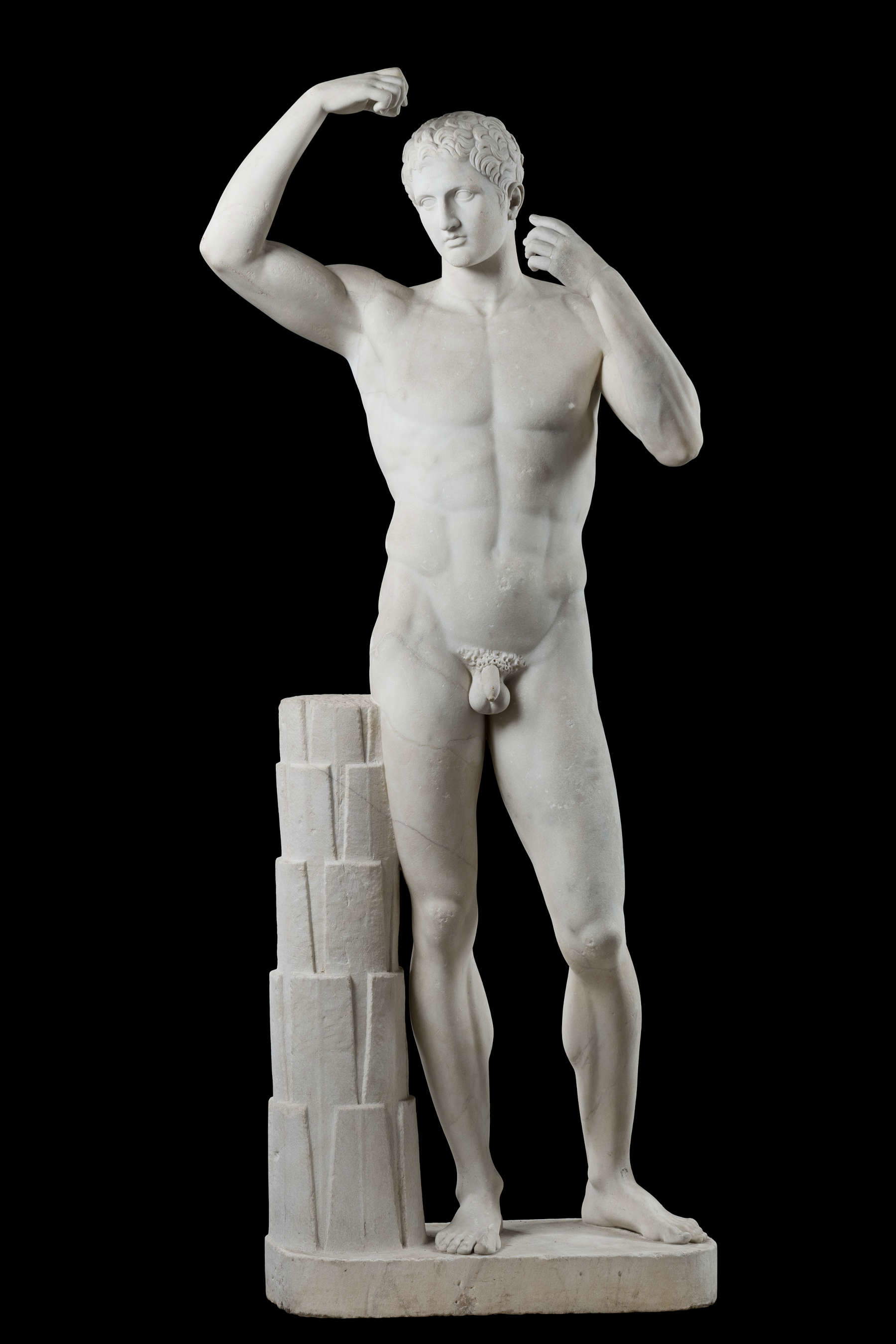

The exhibition tour begins with the section Opera nobilia. The Art of Copying. The practice of copying famous Greek sculptures began to develop in the second century B.C., and in Roman imperial times it became an art form in its own right. Replication of the originals is done by bringing back measurements to guide the sculptor, while dissemination of the models is ensured by the production of plaster casts (some of which have been found in archaeological excavations). Copying the opera nobilia of Greek sculpture became a characteristic and emblematic practice in Roman art, reflecting the formation of a canon of artistically exemplary works. The Torlonia Museum is coeval with the great academic movement that, from the mid-19th century, developed the method of cross-referencing ancient sources and the corpus of Roman copies to study Greek art. The restoration of the sculptures incorporates the progress of this research. The collection includes a number of Roman copies that provide insight into this practice, which originated in the Hellenistic world and reached its peak in the early centuries of the Roman Empire. The artistic quality of the celebrated Greek originals can also be felt beneath the copyist’s chisel. A comparison of two replicas of the original Satyr at rest highlights the problem of copying, which is crucial to understanding Roman artistic practice. While theHestia Giustiniani, whose prototype can be attributed to a master of the early classical age (470-460 BCE) is a sculpture whose quality of execution suggests its provenance from a workshop of the highest level, it is not the only copy to testify to the influence of the originals admired in the imperial era. All the replicas illustrate a fact essential to understanding so-called “cultured” Roman art: the art of the sculptors and the desires of the patrons turn out to be profoundly influenced by an aesthetic culture that looks to Greek models and, more particularly, to Greek masterpieces of the past.

Cultured Art. Styles of the Greek Past is the title of the second section. Pliny the Elder testified in his writings that the preparatory models of the Greek sculptor Arcesilaus, active in Rome in the mid-1st century BCE, sold more expensively than the finished works of other artists. Greek sculptors active in Rome from the 2nd century and especially the 1st century BCE offered Roman customers an eclectic repertoire of forms drawn from the artistic experiences of Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic Greece. They would elaborate new models from these ancient forms, and the activity of the so-called “neo-Attic” workshops would have consequences for Roman art in general that went beyond the field of sculpture: all Roman artists and craftsmen would use these models in numerous areas of figurative production. The Torlonia collection, formed at the epicenter of such flourishing and eclectic activity, bears the imprint of this artistic phenomenon. Figures of maenads from the work of the Attic sculptor Callimachus (late 5th century BCE) are reproduced to decorate luxury marble furnishings, such as the crater in the Torlonia collection. The Albani Cup, decorated externally with scenes depicting the Labors of Hercules, fits into the same vein: artistic researches that have all the characteristics of neoclassicism. The individual decorative scenes testify to the reproduction in the late 1st century B.C., on a different support, of prototypes executed in the second half of the 4th century. The juxtaposition of figures elaborated from stylistically different prototypes is evident on the altar with three deities: Zeus and Athena, with the design of the draperies, the ornamental stylization of the beards and hair, and the almost rigid pose of the figures, are contrasted with the female figure, who is advancing in the opposite direction, characterized by deep, plastic drapery and the natural shape of the hair. As a direct consequence of this cultured art steeped in references, sculptors revisit and mix Greek models, often in an eclectic manner. This proliferation of styles and images underlies one of the most significant characteristics of Roman art:eclecticism.

It continues with the section Entering the Dance. Hellenistic Modernity. The restrospective approach adopted by late Hellenistic sculptors to meet the tastes and demands of Roman patrons profoundly structures the relationship between Greek and Roman art (as evidenced by the works of art found in the Villas of the Roman aristocracy). Nevertheless, the Roman reception of Greek art sees the assimilation of styles and motifs from Hellenistic modernity. Dionysian iconography, as picturesque as the genre subjects, was intended to decorate the domestic spaces of patricians. The exceptionalInvitation to Dance group, found at the archaeological site of the Villa of the Lower Seven, depicting a dancing satyr and a seated nymph, is usually attested in monetary iconography. Images of the Dionysian procession and its ecstasy, used extensively by Neo-Attic artists, offered sculptors an opportunity to develop a Baroque art form, rich in expressiveness and bodily sensuality. The magnificent copy, restored as a bust, of the type of the Drunken Satyr from Herculaneum, whose expressiveness and accentuated movement are characteristic of the researches of the Parchment sculptors of the 2nd century B.C., and the fascinating Silenus type Cesi represent two declinations belonging to the same artistic current of genre subjects. Also traceable to Hellenistic experiences is the development of Egyptizing iconography, allegorical or related to the widespread dissemination of the Alexandrian cults of Isis, Serapis and Harpocrates. Such Hellenistic modernity constitutes another aspect of the considerable influence exerted by Greek forms in Roman artistic culture. Chosen by wealthy patrons, especially to decorate their sumptuous residences, these works of modern taste from the Hellenistic period were found in large numbers in Rome and thus figure in the collection of the Torlonia princes.

The next section is entitled Life of Forms. Originality of Roman Sculpture. Inspired by Greek art, from which it drew most of its artistic and figurative resources, Roman sculpture demonstrates a vitality that results in an entirely new expression: new needs, new genres, new aesthetic and iconographic orientations proclaim the originality of Roman sculpture, as the works in this section testify. The “heraldic” repertoire, the result of reworkings of Greek models by Neo-Attic workshops, is of considerable importance for the development of Roman art. Combining in symmetrical compositions characters in action, it consists of a collection of motifs to be declined at will, where the image, full of generic meanings , acquires a symbolic dimension instead of realistically transcribing the gesture. This compositional principle will be used in the creation of new mythical images, such as the tauroctonia of Mithras, a cult of Persian origin whose image is both narrative and deeply symbolic. The freedom with which the principles of perspective and realistic construction of figuration are used is put at the service of the symbolic function of the image. The relief with a view of the Portus Augusti is unique in Roman art, and with the topographical and symbolic registers mingling vividly, without respecting any rational perspective, it testifies to the lability of the boundary between scholarly and popular art. The iconographic genres and invented typologies adopted to meet the new demands are among the original aspects of Roman art. Images of defeated barbarians, inspired by Hellenistic art, proclaim in a monumental form the power and invincibility of the emperor, and express imperial art in its essence. Finally, the large sarcophagi used for the burial of the dead from the second century CE onward foster the development of the art of relief. Continuous narratives, mythological scenes of a “heraldic” character, allegories portraying the deceased as one of the Seven Sages of ancient Greece, or “biographical” compositions extolling the private or public undertakings of the patron enrich a repertoire of images of surprising vitality, symptomatic of that Roman art that draws inspiration from diverse sources but comes to produce a wholly distinctive expression.

A Common History. Two Sister Collections compares the marbles of the Torlonia Collection and those of the Louvre, which in many cases share a common history; there are numerous works attested in the same collection, in the Renaissance period or in later centuries. From these common origins comes the fact that both collections concretely translate the evolution of the taste for antiquity and the way it is expressed. The antiquities of the Louvre and those of the Via della Lungara thus trace a long history of collecting practices. The collection of the Torlonia Museum and those of Greek and Roman sculpture in the Louvre Museum (until the mid-nineteenth century) seem to be reflected as two sister collections. Some works were found at the same site, albeit under different circumstances, such as the marbles from Herod Atticus’ villa on the Appian Way. Herod Atticus, a great Athenian notable, Roman senator, friend of emperors, philosopher and orator, is one of the most influential figures of the second century CE. Archaeological excavations have revealed several of his residences, both in Greece and in Rome, where he owned a sumptuous villa southeast of the city along the Appian Way. During excavations at the site as early as the 17th century, sculptures and inscriptions were found, which were transferred from the Borghese collection to the Louvre in 1807. In the first half of the 19th century the Torlonia family also undertook excavations in the area that uncovered sculptures from the Athenian senator’s villa. The exhibition at the Louvre is an opportunity to bring together a small collection of works evocative of the personality of Herod Atticus, scattered throughout the history of collections. These fragments hint at the personality of a patron and collector of great cultural depth, close to the imperial court and a central figure in the intellectual circles of the Empire. The sculptures assembled in this section, which constitute a rare record of what archaeology has revealed about Herod Atticus’ holdings and collections, in Rome and Greece, testify to the common topographical origin of the collections. Another link that unites the two collections, according to the expression coined by Salvatore Settis, is the fact that they are both "collections of collections." Before being enriched by the works found in excavations conducted in Greece, Asia Minor, North Africa and the Near East, in the first half century of its life as a public collection the Louvre’s Antiquities galleries-that is, rooms in which sculptures are displayed almost exclusively, according to a pattern that will be taken up in the museum of Alessandro Torlonia-present pieces from the royal collections (purchased largely in Rome from the noble and cardinal collections) and with important contributions from the Borghese and Albani collections. The presentation (on a monumental scale) brings together sculptures that were at the same time in the collections of the illustrious Savelli, Cesi and Medici families in the 16th century, and in the Albani collection in the 18th century, revealing a multiplicity of paths that write the rich and complex history of antiquities collections between the Renaissance and the 19th century. The ancient work as an object of aesthetic delight and prestige, a model for artists, a symbol of an ideal of civilization, and an object of knowledge, is at the heart of European culture and the idea of the museum that gave rise to the Louvre.

The passion for Antiquity in early Humanist Rome long preceded the idea that these ruined fragments of ancient Rome should be restored and completed. Early descriptions of Roman palaces, such as those of the courtyard of the Palazzo Savelli at the Teatro Marcello, but especially the drawings of Martin van Heemskerck and Pierre Jacques, reveal how these collections were generally presented in the fifteenth century: fragments of sculpture, arranged in no apparent order, appreciated as ancient ruins. In the first decades of the sixteenth century, a new aesthetic model takes hold: the antique piece becomes an aesthetic object somewhere between Antiquity and the modern era. Completing fragmented statues becomes a subject for artists, primarily for sculptors, who see in it an opportunity to grapple with the ancient style; but it is also a subject for patrons, who seek to create harmonious compositions within suburban palaces and villas that play the role of a palatial decoration. The history of the restoration of antiquities is thus one of transforming the expectations of collectors, on the one hand, and the approach taken by sculptors, on the other: from the virtuosic polychrome marble restorations of the seventeenth century to the archaeological restoration practiced at the Torlonia Museum in the 1870s, via the literary approach inherited from the Renaissance, the main trends that characterized the assimilation of ancient sculpture by moderns will be traced in general lines, through concrete examples, until the advent, in the nineteenth century, of the archaeological object in its dignity as a fragment.

|

| Masterpieces from the Torlonia Collection go on display at the Louvre |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.