From May 17 to September 22, 2019, the Rietberg Museum in Zurich is hosting the exhibition Mirror. The Reflection of the Self, an exhibition tracing the millennia-long cultural history of the mirror: from ancient Egypt to the Maya in Mexico, Japan, Venice, or spanning film and contemporary art, civilizations around the globe have made mirrors, ascribing different meanings and powers to them. Through a selection of 220 works of art from 95 museums and collections around the world, the many craft and technological developments of this reflective medium, as well as its cultural and social significance, are illustrated. Protagonists of the exhibition are mirrors as artifacts, but it also discusses the mirror as a symbol of self-awareness, vanity, wisdom, beauty, mysticism, magic and, last but not least, what is the mirror of our times: the selfie, which has become a mass phenomenon of gigantic proportions, with millions of self-portraits, taken at arm’s length and posted under every possible hashtag.

The exhibition, curated by Albert Lutz, begins with the myth of Narcissus: the story of the young man who falls in love with his own image reflected in a pool of water and dies consumed by despair that his love was hopeless, has nourished the imagination of creative spirits for centuries: the myth of Narcissus has thus become a recurring theme in literature, philosophy, art and psychology, called into question whenever it is a matter of self-love, life and death or self-esteem. It continues with the Renaissance, a time when the study of one’s face in the mirror aimed at its transposition into a self-portrait became established throughout Europe as a genre of art in its own right. In more recent times, photography has multiplied the possibilities of artistically staging oneself, whether through the self-timer or through the reflection of a mirror. On the theme of self-portraiture, the exhibition brings together a women’s selection of work by twenty female artists and photographers from four continents from the 1920s to the present. The selection includes photographs ranging from Claude Cahun to Florence Henri to Amalia Ulman and Zanele Muholi via Cindy Sherman and Nan Goldin, and the works offer glimpses of the artists’ ateliers, illustrate their artistic practices and provide a glimpse into their daily lives between family and work to the intimate sphere of their private lives. And again, film clips (featuring men talking to themselves in mirrors and gunmen shooting mirrors instead) aim to serve as a witty counterpoint to the women’s portraits.

In Zurich it is then possible to take a trip around the world on the trail of the history of the mirror as a physical object: obsidian mirrors (a black-colored volcanic glass) produced seven thousand years ago and found in the Neolithic tombs of Catalhöyük in Turkish Anatolia are now considered the oldest archaeologically documented mirrors in the world. These polished mirrors were part of grave goods, but it is unknown for what purpose. In pre-Columbian America, in addition to obsidian, other minerals such as pyrite or hematite were used in the manufacture of mirrors, while with the flourishing of bronze cultures in Mesopotamia, Egypt and China polished metal mirrors, mostly round in shape, became widespread from the third millennium B.C. These mirrors served not only for ritual or funerary purposes, but also for cosmetic care of the face. The exhibition begins its journey through history on the trail of the mirror’s history with an Egyptian bronze specimen dating back to the 19th century B.C., which a father specially commissioned for his daughter “for the observation of the vis” (as the inscription reads). The journey then takes the audience to Greece, Rome, Etruria and the Celts, as well as Iran, India, China and Japan. Singular pieces from the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City hint at the arcane power the Maya and Aztecs attributed to the mirror. Artistic depictions of women looking at themselves in a hand mirror at the bath or while combing their hair adorn the backs of Greek, Roman and Etruscan mirrors. Also on display are masterpieces from the Louvre in Paris and the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The transformation of glass into mirrors began in Europe, if we exclude the earliest examples from Roman times, in the 13th century in Central European and Italian glassworks. The Murano/Venice glass mirrors that dominated the world market and the mirrors created for the French palace at Versailles by the Saint-Gobain workshops constitute the pinnacle of European production from the 16th to the 18th century. The manufacture of these mirrors silvered on the back by an amalgam of tin and mercury often led artisans to an early death from exposure to toxic vapors. German chemist Justus von Liebig’s invention of a process for silvering glass without the use of harmful substances led, beginning in the 1860s, to the large-scale production of the mirror, made by depositing a thin layer of silver or, especially today, aluminum on a sheet of glass. The journey through the history of the mirror culminates, finally, in works by Fernand Léger, Roy Lichtenstein, Monir Farmanfarmaian, Anish Kapoor and Gerhard Richter, all of whom share the title Mirror, undoubtedly proving the constant predilection accorded to this shimmering surface in modern and contemporary art, both as a motif and as a working tool.

The exhibition also explores the concept of the mirror as a symbol of virtue, sin, wisdom, vanity, magic, protection, defense, with representations of the mirror from all eras: in European art of the Middle Ages and the modern age, personifications of wisdom were often depicted holding a mirror, for wise is he who recognizes himself and with shrewd prudence reflects on the way forward. However, the attribute of the mirror also recalls one of the seven deadly sins, pride, for proud and vain is he who often looks at himself in the mirror self-satisfied and lives listlessly thinking neither of the past nor of the future. But the mirror, also hints at an image of fragility, and faithfully reflects details but can also be dark and mysterious, so it is commonly seen not only as a harmless reflective medium but also as a powerful tool that interacts with our lives by advising us or revealing secrets, something that can protect but also pose a threat. It is no wonder, then, that surrealist art has resorted to the mirror (think of the works of Salvador Dalí or Paul Delvaux), to symbolize abyssal depths, unknown or arcane dimensions. The protective function of the mirror is evidenced in the eighteenth-century robe of a Siberian shaman, the oldest in the world, littered with brass mirrors, but fetishes equipped with mirrors from the Congo also testify to how, according to beliefs, these “reflectors” warded off evil forces, thus protecting the wearer. And again, in almost every major religion, whether in Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam or Christianity, one finds texts describing mirrors as metaphors for the soul, emphasizing how the latter must always be thoroughly polished so that not even a speck of dust can tarnish it.

The mirror then also embodies the theme of beauty and seduction, illustrated at the Rietberg Museum by Indian and Japanese paintings, prints and photographs, as well as European paintings dating from the 16th and 17th centuries. These are women caught putting on makeup, adorning themselves, bathing while looking in the mirror while waiting for their beloved or, in turn, being watched by men. Although in European plays there was a primary tendency to place women in the mirror in a moralizing context (they were in fact supposed to visualize sinful vanitas) the purpose for which they were created is evident. They are mainly scripts designed by painters or photographers for the benefit of male observers. In fact, women usually appear in them nude or unclothed. The images allow the man to penetrate the environments reserved for women, places where he was mostly forbidden access. In some depictions we see reflected in the mirror the face of the woman portrayed: the very one we believe we are spying on peers back at us and consciously condescends to our presence.

The exhibition concludes with the story of Alice, who wanders into a wonderland beyond the mirror, as well as with a significant work by Michelangelo Pistoletto and a clip from Jean Cocteau’s film Orphée in which French actor Jean Marais in the guise of Orpheus accesses the underworld through a mirror. The exhibition then extends outside the museum: on the plaza in front of the museum, visitors discover a park of mirrors, a pavilion made of colored, reflective glass. The location, an interweaving of reflected visual perceptions and acoustic experiences, serves almost as “selfie land,” an ideal backdrop for self-portraits and group photos. In addition, lenticular mirrors, the work of German artist Adolf Luther, float in the pond at Villa Wesendonck, and next door, on the lawn, is placed a work by Silvie Fleury entitled Eternity Now, an oversized rearview mirror in which both the park and the villa are reflected.

Finally, of note, with Mirror. Reflection of the Self, curator Albert Lutz bids farewell to the museum he has managed since 1998: the exhibition, in which all of the Rietberg’s curators and curators collaborated, thus represents a kind of “rearview mirror” for the outgoing director. More than twenty outside experts were also involved, who as co-curators and authors joined the museum’s curators and contributed to the catalog. For more info you can visit the Rietberg Museum website (in German, French, and English).

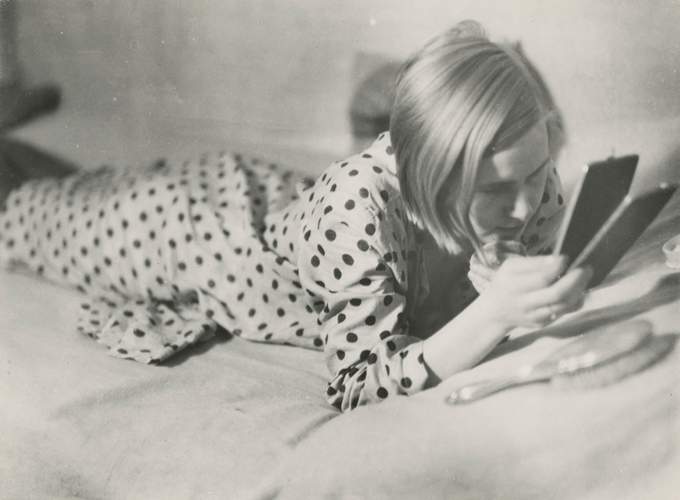

Pictured: Marianne Breslauer, Girl in her spare time, Berlin 1933 (1933-1934; gelatin silver print, 17 x 23.5 cm)

|

| The history of the mirror, from ancient Egypt to the present, on display in Zurich with 220 works |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.