Francesco Guzzetti, born in Lecco, Italy, in 1988, is a young Italian scholar who has been undertaking in-depth and original research on Arte Povera for some time. After receiving his doctorate from the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, he moved to America, where he worked at the Italian Center for Modern Art, Harvard University, and then at the Magazzino Italian Art foundation, for which he curated the exhibition Paper media: Boetti, Calzolari, Kounellis at the Samuel Dorsky Museum in New Paltz (New York). Francesco Guzzetti is currently a Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Drawing Institute of the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, where he will remain until summer 2020. He has been in the United States for four years and has gained significant experience in his field of study.We spoke with him about his research on Arte Povera and tried to understand what are the differences between studying art in Italy and doing it in the United States. The interview is edited by Ilaria Baratta.

|

| Francesco Guzzetti. Ph. Credit Marco Anelli, 2019 |

IB. Until July 2019, you were the first “Scholar-in-Residence” of Magazzino Italian Art, based in Cold Spring, New York, and are curator of the current exhibition Paper media: Boetti, Calzolari, Kounellis at the Samuel Dorsky Museum. How do you experience these highly relevant roles?

FG. It’s a great privilege and it’s a great opportunity: the curatorship of the Dorsky exhibition came about as a consequence of my fellowship at Magazzino, which lasted a year and came about at the suggestion of director Vittorio Calabrese and founders Nancy Olnick and Giorgio Spanu. However, I was already in the United States from before, with a fellowship at Harvard, in the context of which I met director Calabrese, and from this proposal this extraordinary experience was born: this one at Magazzino was a great opportunity both for my research work (from my doctoral thesis onward I have always dealt with Arte Povera), and from the human point of view. As a conclusion of this fellowship year of mine at Magazzino, during which I assisted Nancy and Giorgio in the creation of a research center (moreover, a structure was created that over the years will be increasingly effective and efficient, as well as ready for the needs of future fellows), came the proposal to curate this exhibition: the project also stems from Nancy and Giorgio’s desire to create a network of collaborative relationships between Magazzino and institutions in the Hudson Valley, which is a treasure trove of cultural centers, museums, institutions and private initiatives (even I had no idea before I got here!). Magazzino has had a pretty amazing response from the community: amazing because Magazzino is an Italian art museum, so there is no direct link to the cultural background of this area, however the response from the local communities has been really fantastic, and by virtue of that Magazzino is trying, and will try over the years, to create collaborations. Also for this reason, a collaboration has come about with the Dorsky Museum, which is the museum of SUNY - State University of New York, a very large network of universities involving the Manhattan area and other centers in upstate New York including New Paltz, a city in the Hudson Valley on whose campus this museum is located, which is also very important from a collection point of view. In trying to find a theme that would draw from Nancy and Giorgio’s extraordinary collection, I thought, partly because of my specific current research themes, that drawing might be an interesting topic, and that’s where the exhibition project came from, based on the fact that there are particularly significant cores of works on paper in the collection by the three artists in the exhibition. We could have done this with other artists as well, but I have to say that the nuclei of works on paper by Boetti, Calzolari, and Kounellis in the Olnick Spanu Collection are really of very high quality.

What are the most important pieces among those on display?

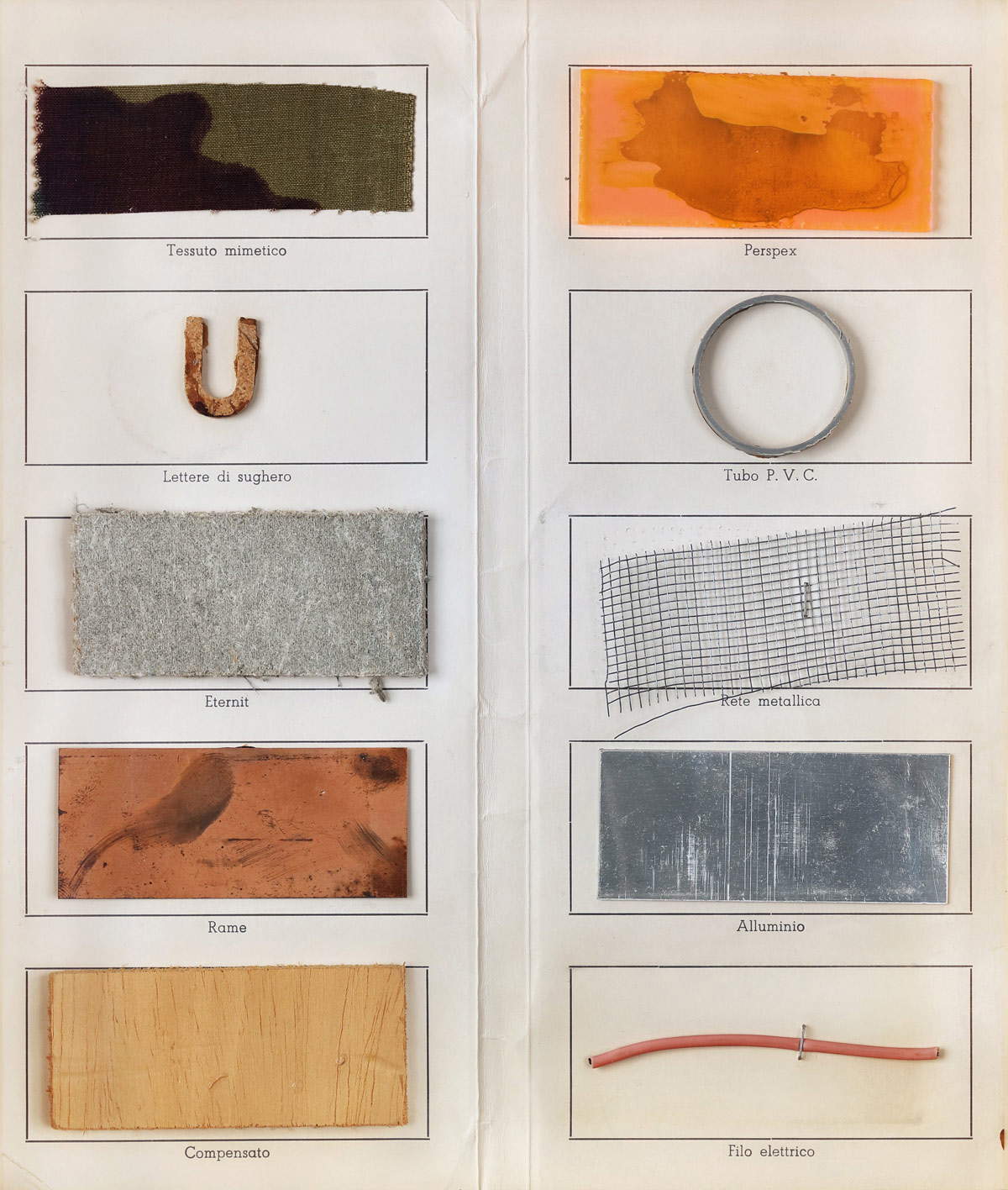

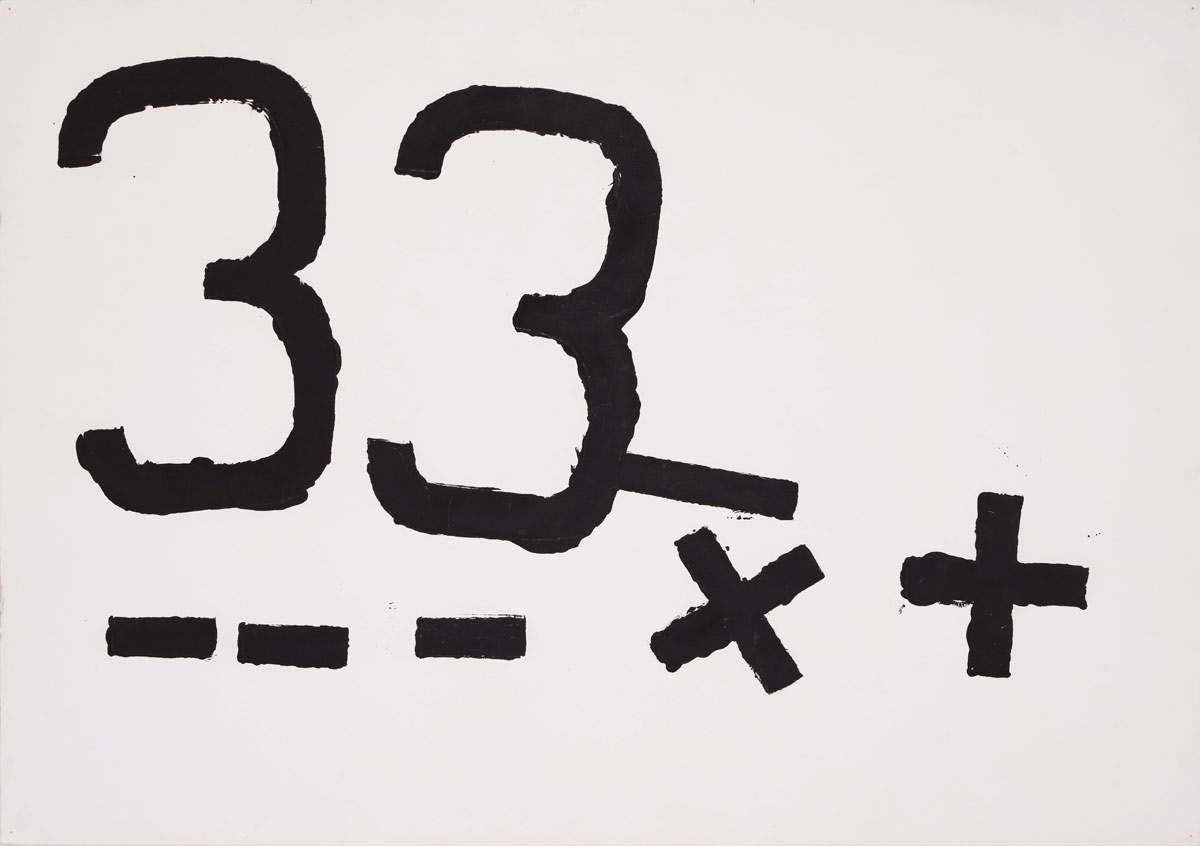

It must first be premised that, to my knowledge, this is the first exhibition devoted exclusively to Arte Povera works on paper in the United States. In general, that of drawing in the practice of the artists of those years is a topic that is still not well studied. Actually, in recent years there have been several occasions, several studies, monographs, articles that have thrown some light also on the practices of some artists in particular, from Paolini to Penone, and some insights have been made in recent years, however an organic reconnaissance is still lacking. I think only one group exhibition has been done so far, dedicated only to Arte Povera drawings: an exhibition that Gianfranco Maraniello curated in Porto Alegre, Brazil in 2014, and that was the only occasion where some point was made about the practice of drawing in Arte Povera in general. There have then been studies of individual artists and there have been previous anthologies of drawing, but there has not yet been an organic and in-depth study of drawing practice in Arte Povera: the exhibition would like to shed some light on this topic, particularly in the United States, where I think this is the first time that such an exhibition has been done, which also has to do with my current research themes and which now, having finished the fellowship at Magazzino, I will continue at the Morgan Library in New York precisely with a project on drawing in Arte Povera. There are some very important pieces, and if I have to mention some of the significant ones I could mention, for example, a work on paper from Kounellis’ Alphabets series from 1960, three works by Calzolari from the historical years not only of the artist but also of Arte Povera (1967, 1968, 1969: and by the way now in Naples there is also the exhibition on drawing and painting in Calzolari’s work), and again by Boetti there are resounding things, such as a specimen of the famous invitation to Boetti’s first solo show in 1967 at the Christian Stein Gallery in Turin (invitations in which Boetti had glued pieces of each of the materials of which the works shown in the exhibition were made), there is a very nice print run of the portfolio dedicated to the twelve forms from June 10, 1967. There is a large sheet from 1980 by Kounellis, populated with ink heads reminiscent of Munch. The exhibition is not very big, in fact it is quite small in terms of numbers, but we tried to select quality works that could restore (even to an audience that is not necessarily familiar with either Arte Povera, these artists, or drawing in Italy in those years) the importance of this practice and give the sense of this work even going beyond the historical chronology of Arte Povera (because we start in 1960 with Kounellis and go to 1987 with Boetti). So the idea is also to focus, within the limits of a small exhibition, on the premises and continuation of these artists’ work even after the three to four historical years of Arte Povera.

|

| Exhibition Paper Media: Boetti, Calzolari, Kounellis, curated by Francesco Guzzetti at The Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, New Paltz, through Dec. 8, 2019. Ph. Credit Alexa Hoyer |

|

| Alighiero Boetti, Untitled (Stein Invitation) (1966-1967; paper, camouflage fabric, Plexiglas, cork, P.V.C. tube, eternit, wire mesh, copper, aluminum, plywood, electrical wire). Courtesy Olnick Spanu Collection |

|

| Pier Paolo Calzolari, Untitled (1968; rock salt, painted cardboard). Courtesy Olnick Spanu Collection |

|

| Jannis Kounellis, Signs (1960; tempera, glue on paper). Courtesy Olnick Spanu Collection |

The Magazzino Italian Art Foundation is a Center for Research on Postwar and Contemporary Italian Art and also provides an annual grant program for funding emerging scholars pursuing independent research projects. Through your current exhibition, the first in America on this movement, you are introducing Arte Povera to the United States, particularly the works on paper by Boetti, Calzolari and Kounellis. So can it be said that America has discovered an interest in Arte povera and in Italian art from the postwar period onward? From what was this interest generated?

Certainly on the one hand, there is a tradition of exhibitions in America devoted to Italian art of the Postwar period and also to Arte Povera artists: think of the Young Italians exhibition curated in 1968 by Alan Solomon (who had also curated the infamous U.S. pavilion of the 1964 Biennial) at the Jewish Museum in New York, and there were Kounellis, Pascali, Castellani, Bonalumi, Ceroli, Pistoletto and many others. They constituted the new generation of Italian artists then, and it was a very epochal exhibition. Then there were some individual museums that did monographic exhibitions on some important artists: for example, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis did exhibitions on Pistoletto, Fontana, Mario Merz. Galleries do so much: the Sonnabend Gallery has been organizing exhibitions of Arte Povera artists in New York since the late 1960s, and so then does John Weber. Then consider a further pivotal moment, namely The Knot exhibition devoted to Arte Povera and the Italian art of that generation, which Germano Celant curated at PS1 in New York in 1985 (then Celant would curate, a few years later, the major Mario Merz exhibition at the Guggenheim). In short, there are various moments of interest, both for individual figures and in general for Italian art and Arte Povera in particular in the United States. It is true that, also in my opinion, there has been a consistent upswing in recent years, which on the one hand has to do with a whole area that I know very little about and that is the market: consider that in 2017 alone there were, more or less at the same time, in three of the most important galleries in New York, three exhibitions dedicated to Arte Povera (Hauser & Wirth was presenting the exhibition of the Goetz collection, an extraordinary collection, of very high quality, of Arte Povera, at Levy Gorvy there was the exhibition Ileana Sonnabend and Arte Povera, curated by Germano Celant, with the works of Arte Povera artists presented by the Sonnabend Gallery between Paris and New York in the 1960s and 1970s, and then Luxembourg & Dayan, which often deals with things Italian, organized an exhibition on the legacy and fortune of Arte Povera artists, who were compared with artists of later generations). Then of course there are the galleries representing Arte Povera artists, for example Marian Goodman, Marianne Boesky, or Gagosian representing Penone (last year, moreover, an important summary volume on all of Penone’s work, edited by Carlos Basualdo, curator of the Contemporary Art Department of the Philadelphia Art Museum, came out for Gagosian). At this moment there is a strong interest in Arte Povera, for market reasons and for reasons of cultural interest: it is a particularly good moment, and on this Magazzino is in a dual position, in the sense that on the one hand it is a mirror of the situation of the time at this moment, but on the other hand it has also anticipated a great deal, anticipating an interest that is developing in these years. Even the exhibition that there was on Lucio Fontana at the Met Breuer (as much as it also tried to find Latin American roots in Fontana’s work), or the Burri exhibition at the Guggenheim curated by Emily Braun, are other traces of this interest. An interest that then, moreover, also extends to figures like Vincenzo Agnetti or Fabio Mauri, who played a fundamental role in those years even though they were not part of Arte Povera. Let’s not forget that today we tend to make the art of those years coincide with Arte Povera, but there were nevertheless very relevant figures who remained outside of it.

You have curated exhibitions both in Italy (in Lecco, Milan) and in the United States. How does it change, if at all, in your opinion, the role of the curator in Italy and America?

I can say that, for this last experience of mine, the fact of being able to rely on a very strong team like Magazzino and on a team of great professionals like Dorsky’s (the exhibition is co-produced) has also allowed me to be able to devote myself more to the work of choosing the works, setting up the exhibition, and the catalog (the exhibition will have a challenging catalog, in the sense that a lot of research work has been done on the individual pieces, which are largely unpublished). In short, the fact that I had time to devote myself fully and freely to this work (especially to the writing of the catalog, which for me is fundamental) is a great advantage, which I did not find in my experiences in Italy: in Italy one had to be ready to intervene on any front of the enormous machine that an exhibition moves (from bureaucratic to organizational aspects). Here, maybe in Italy we need to be a little more present at 360 degrees.

|

| The headquarters of Magazzino Italian Art. Ph. Credit Marco Anelli |

|

| The Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art |

In addition, you have studied and taught at prestigious universities, such as the Scuola Normale in Pisa and Harvard University. What prompted you to head to America? How different do you think the educational offerings in education in Italy and America are?

I more than anything else have been doing research, and personally, until a few years ago, I didn’t know that I would like to experience the United States so much: it all started because I made anapplication when I was still a doctoral student at Normale for a foundation in New York, the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA) created by Laura Mattioli. I have to say that it was a beautiful, unforgettable and fundamental experience for me: beyond the very nice memories related to CIMA, it was the opportunity to live in New York for a long period (a year), such that you realize that the size of this city is totally different from ours, from the point of view of liveliness and vitality (even too much perhaps, in the sense that it comes back difficult to follow everything). In the United States, however, there are so many opportunities, especially when you are a first-time visitor, because the enthusiasm is general. From there I decided that I would like to try to stay in the U.S. a little longer and therefore began to make more applications. The nice thing that America offers is just the applications: there are a lot of them, both at universities and research centers, which have many semester-long or year-long fellowship programs. Usually you go for quantity, meaning that you try to do as many as possible and hope that at least one will go well. And another interesting aspect is that within fellowships you make relationships that then open up other possibilities. The differences with Italy are there but they are not always positive: it is true that there are many opportunities, but it is also true that the competition is very strong, in the sense that there are thousands of people trying to compete for the same opportunity. However, the idea of absorbing the work of scholars from abroad in the research centers of American universities is very strong, here it is a tradition: Italy does not have this tradition, beyond a few centers (I am thinking for example of the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence, the Hertziana in Rome, the American Academy in Rome, the Academy of France in Villa Medici: all centers that moreover have foreign affiliations, proving that Italy, on its own, hardly does things of this kind).

Do you advise young Italian scholars to go to the United States, or at any rate abroad, to get more satisfaction?

In my opinion, beyond the satisfaction it can give, an experience abroad is useful in general. I for one also think back to the possibility of returning to Italy differently than I did a few years ago. After the experience at the Center for Italian Modern Art, my dream was to stay in the United States. Now I also think back to the idea that maybe at some point it would not be bad to return to Italy: it is true that the academic structures are very different (for example, American doctoral students teach, Italian ones do not), but in general even an experience of only a year, if not a few months, could be useful, because it opens the mind. You get a sense of another dimension, and it’s a cultural background that is good for you even when you go back to Italy, in case you want to do that. So it’s advice I definitely give.

In conclusion, what are your future plans?

I now have a one-year research fellowship at the Morgan Library with a project on drawing in the practice of Arte Povera artists, especially in the 1970s, in dialogue with American postminimalist and conceptual art. I am also trying to work on a book idea on these topics, which I will start on next year. In the meantime I will do more applications to do another year of U.S. after Morgan, and then I would like to start getting teaching experience-that’s the perspective I like. Right now, though, I’m staying focused on current projects!

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.