A digital campaign of the Ministry of Culture dedicated to the creative processes of the great artists and literary masters of Italian history, from Caravaggio to Grazia Deledda, from Raphael to Giovanni Pascoli, from Sandro Botticelli to Ugo Foscolo. The new voyage of discovery of the state’s cultural heritage is titled Artist’s Second Thoughts and chronicles the uncertainties and doubts that accompanied the tormented creative processes of the masters and masters of Italian art and literature, from the initial inspiration to the final result.

Each week, on MiC’s social channels, the campaign will be declined in two different narrative strands: one dedicated to the visual arts, the other to the world of writing. The first, in particular, will unveil what lies beneath the pictorial layers of the most famous masterpieces housed in the state’s museums, galleries and art galleries: a narrative that talks about the difficulties of the creative process and how, at the end of it, the artist was often left dissatisfied with the work created. The second column of the digital campaign, on the other hand, tells of the many revisions behind the “paper masterpieces” kept in archives and libraries, such as pencil marks, margin notes, notes and erasures, all clearly evident in the margins of typescripts or autograph manuscripts: evidence of the frequent reworking to which the texts of novels, essays, articles, tragedies and poems were subjected before being consigned, with their publication, to the dimension of eternity.

Of these perplexities, repentances and corrections we preserve the traces: the changes imagined by artists and literary figures remained on canvases, boards and worksheets. There are, for example, corrective brush touches, scribbles, accidental ink stains, and stanzas entirely removed or replaced. The campaign thus aims to bring the public into theintimacy of the work of artists and writers, extracting parts edited by the authors themselves out of a heartfelt necessity: it will thus be like getting to know the soul of the authors, because observing the regrets allows one to discover not only the dynamics related to the conception of the work, but also hidden traits of their personality.

In works of art, many of the artists’ second thoughts can be appreciated with the naked eye, while others can only be seen through restoration procedures and the most advanced analytical and diagnostic investigation techniques applicable to works of art. Still, additional campaign documents unveil drawings and preparatory studies of sculptures and monuments, report architectural plans of buildings and neighborhoods, decorations of bookcases and ceilings, all conceived in a different mode than executed. Then, with a special magnifying glass, the masterpieces of some of the masters of the Italian Renaissance and Mannerism will be explored in depth through dedicated articles.

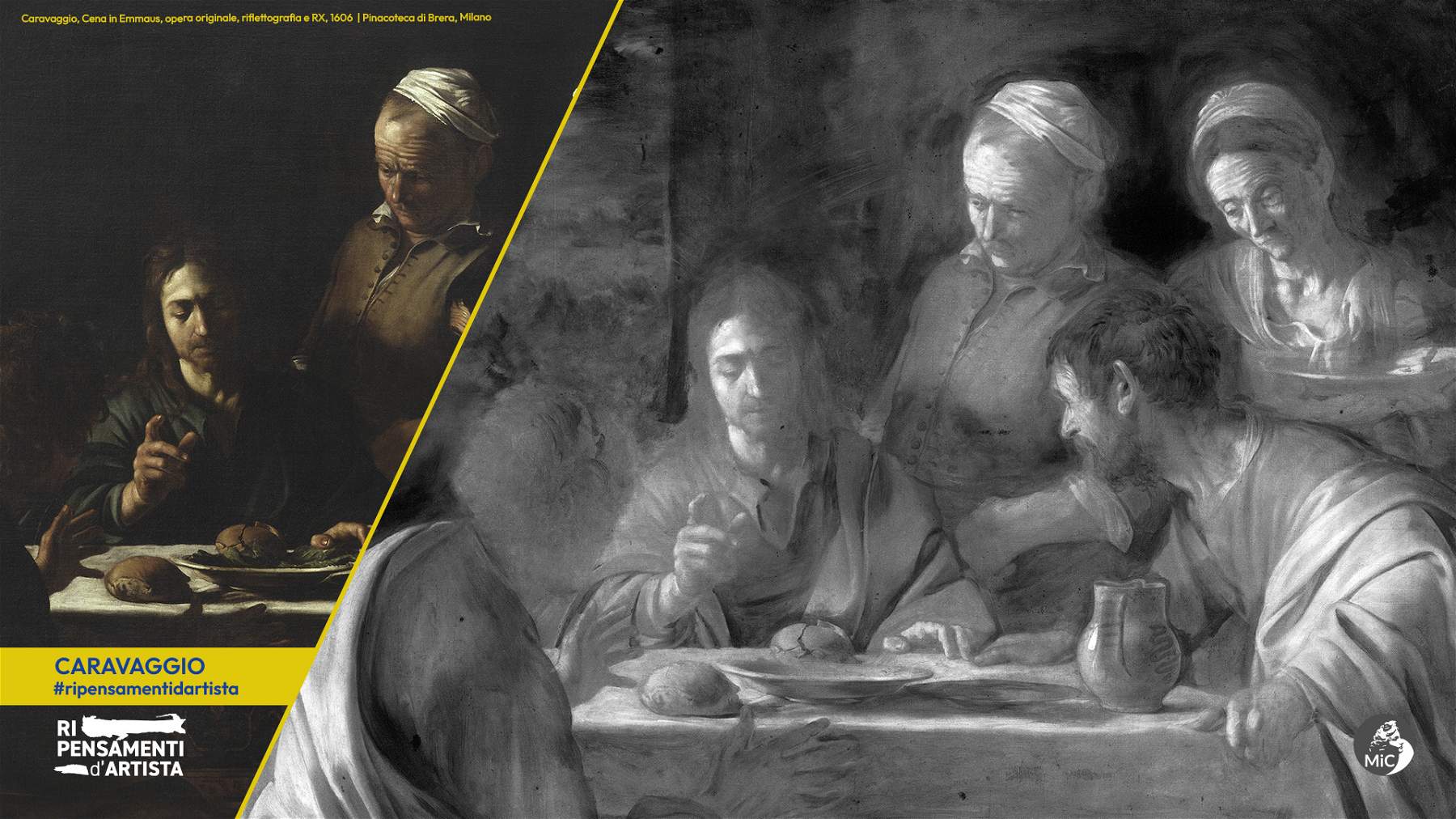

There are, for example, strange eyes hiding between the folds of Saint Catherine of Alexandria’s dress in Botticelli’s Saint Ambrose Altarpiece preserved in the Uffizi Galleries. Or again, the face of a Saint Joseph appears on the white cloth that the other Saint Joseph of the Zingarello Nativity in the National Gallery of Apulia holds in his hands. The great Domenico Beccafumi originally designed his Madonna in the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena while holding the child on the left side, not the right side as we see it today. Rethinking even on well-known masterpieces: the Museo Real Bosco in Capodimonte preserves, among many other masterpieces, the Crucifixion by Masaccio, one of the initiators of the Renaissance, whose work underwent a restoration in the mid-1950s that allowed the recovery of the iconographic detail of the Tree of Life, hidden by a 17th-century repainting. From the fifteenth to the sixteenth century, analyses performed on Titian’s Danae, also in Capodimonte, indicate that the reclining maiden was initially a Venus, the goddess of eros. And again: the mythological animal that holds Raphael’s Lady with the Unicorn in the Galleria Borghese, was previously a small dog; the Hippogriff in Giovanni Lanfranco’s work housed in the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche originally had outstretched wings; the Rython preserved in the Gioia del Colle Museum, now in the shape of a deer, once had the configuration of a horse’s head; infrared reflectography performed on Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus in the Pinacoteca di Brera revealed the presence of a landscape background, which was never realized. It is precisely from this work that the campaign logo takes its cue, which reworks a small detail of the painting: a brushstroke discovered thanks to diagnostic analysis that showed that in an early version of the painting, on the left side of the canvas, where there is now a brown wall, a window, or part of a loggia, had been made that opened onto a landscape. Finally, in an original animation, some digital erasures will bring out the name of the countryside from a written composition.

As for literature, we know, for example, that the famous novel L’Edera by Grazia Deledda, Nobel Prize winner for literature, was originally supposed to be called “Romanzo Sardo,” as evidenced by the author’s originals preserved at the National Library in Sassari. And again, one of Giovanni Pascoli’s most prized poems, Il poeta solitario (The Lonely Poet), was conceived differently, as evidenced by the drafts of the poem in the Mario Novaro Foundation Archives in Genoa, replete with deleted lines and new stanzas written in the margins. Many times the octaves of Canto 46 of Ludovico Ariosto’sOrlando Furioso in the National Library in Naples have also been corrected and revised. And the first prints of the Zanardelli Code, kept by the State Archives in Brescia, reveal the modernity of the new penal code that first abolished capital punishment throughout Italy, while most European countries still used it.

The state’s museums, libraries, archives, and places of culture, adhering to the initiative, have carried out painstaking research work in their collections, bringing to light a considerable amount of documents and evidence. For the figurative arts, a significant contribution has come from the Opificio delle Pietre dure of Florence, one of the most important institutes in the field of restoration at the international level, which, thanks to its activity in this field, has built up over the years an archive rich in images resulting from diagnostic research techniques, such as infrared reflectography, imaging spectroscopy and digital radiography, applied to those works kept in the most important museums of the State and arrived at the Institute for restoration purposes.

To discover these stories, therefore, it will be enough to connect to the MiC’s social channels: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Youtube, and Tiktok.

|

| Artist's second thoughts: a MiC campaign to uncover authors' regrets |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.