This is the third part of aninvestigation of Pompeii, which comes at the conclusion of the Great Pompeii Project. After having dealt with the relationship between the archaeological area and the territory and the Park’s communication, in this last part we will deal more specifically with the Great Project costing 105 million euros, which was born within the framework of the European Regional Development Fund.

The “Grand Project for the Protection and Enhancement of the Archaeological Area of Pompeii” was created in 2013 as an “extraordinary plan of conservation intervention, protection, restoration and enhancement of the archaeological heritage of Pompeii.” On Feb. 18, Minister of Cultural Heritage Dario Franceschini could declare that “the 105 million euros earmarked for the Great Pompeii Project have all been spent and well. Now we have allocated another 50 million euros to continue the work because in Pompeii the work will never end, there are 22 hectares still to be excavatedand the city requires continuous maintenance and research. The results of these years are there for all to see.” The project with which the funds were obtained, however, did not plan to use them in excavation operations, because, as we saw in the second part of the investigation, money for maintenance is never enough. There is also more, however, which the minister rarely talked about.

|

| Pompeii, via delle Scuole. Ph. Credit Carlo Pelagalli |

|

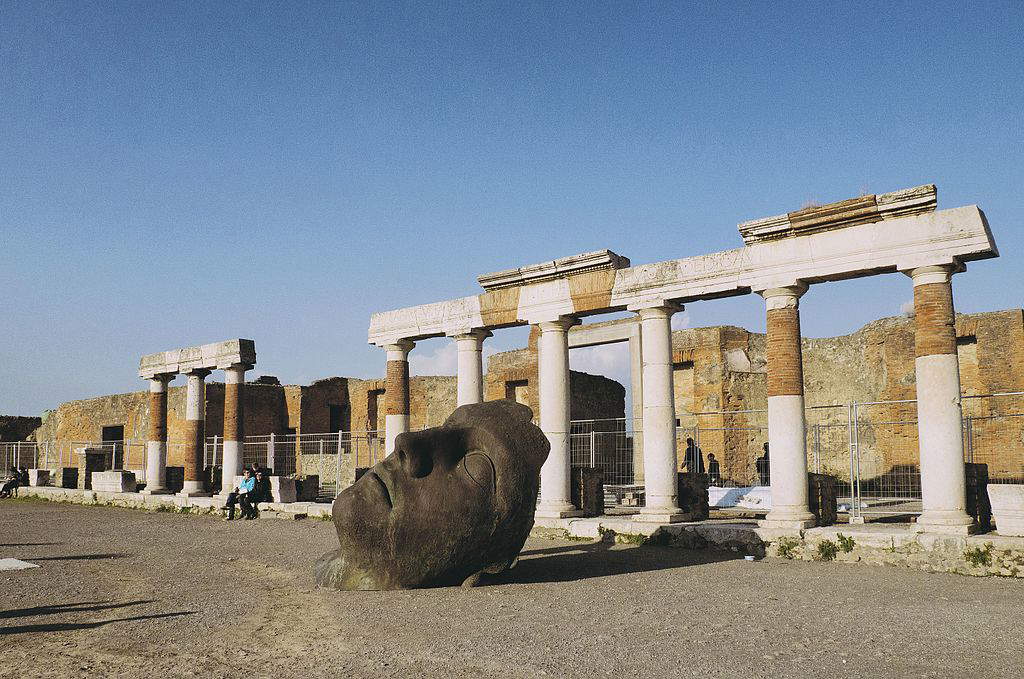

| Pompeii, the Forum. Ph. Credit Brunella Pastore |

|

| Pompeii, the Basilica |

|

| View of Pompeii. Ph. Credit Sébastien Amiet |

The Park of Pompeii

The Pompeii Archaeological Park, in spite of its name, includes not only the site of Pompeii but comprises nine different sites. Four of these (Longola, the Castle of Lettere, Villa Sora, and the Bourbon Powder Mill) are incorporated into the Pompeii Park the moment it ceases to be the Superintendency of Pompeii, Oplontis, Boscoreale, and Stabiae, in 2014. An operation that thus places Pompeii as the head of a grouping of very diverse sites, ranging from the Iron Age to modern times. The more than one hundred million of the Great Pompeii Project was intended to be invested in such a way as to enable the development of the entire Vesuvian area, in which the excavations of Pompeii were to be only the main driving force. For this very reason, the management committee of the Great Pompeii Project is composed of three ministers, the president of the region, the president of the province, and the mayors of nine municipalities in the Vesuvius area. The committee met three times in 2015, once in 2016, and once in 2018. On that occasion, regarding the Strategic Plan that had just been launched by the committee, Minister Franceschini stated, “In these four years, a remarkable work has been accomplished on the excavations of Pompeii, recognized worldwide. Now it is a matter of governing the impetuous growth of international tourism to make this work a lasting factor of development for the entire territory.” Since that day, the management committee has not met, and the funds have run out.

How are they, the other sites of the Pompeii Archaeological Park? The Longola Archaeological Park, which opened in 2018, was visited by volunteers for a few months and has since been “temporarily closed for maintenance.” The Polverificio Borbonico, which was to be used to “find new and more suitable spaces to be used for state-of-the-art storage, archives, laboratories, auditorium, exhibition spaces and offices,” is not visitable and no construction site appears to have started. Villa Sora is closed, or rather can be visited occasionally with the help of a group of volunteers. Boscoreale’s antiquarium was visitable until the March 2020 closure, but has never reopened since, for unknown reasons. Oplontis has always been visitable, albeit in need of urgent restoration. Villa Ariadne in Stabiae is visitable, although between 2018 and 2019 it was closed for six months after a roof collapsed due to bad weather. The Castle of Lettere is visitable, by the municipality. While the Reggia di Quisisana in Castellammare di Stabia has for the past few months become the local museum. In conclusion, of the nine sites pertaining to the Pompeii Park, four are not visitable at this time. Or rather, only Pompeii and the Stabia museum, the only ones to have reopened last Monday, in a hierarchy of reopenings that even in June had left the less famous sites behind, are visitable at this precise moment.

This hierarchical management has had consequences: in the Vesuvius area, the exponential growth of visitors to museums, due to a favorable international trend (+27 percent between 2014 and 2019, but part of a steady growth since the 1990s) has not led to widespread tourism growth in the area. As mentioned in the first part of the survey, tourists were concentrating in Pompeii and then leaving. The Pompeii archaeological area saw a 30 percent growth in visitors between 2014 and 2019, even higher than the national average, despite starting from the huge base of 2.7 million annual visitors. No other site pertaining to the Park has grown so much, percentage-wise, despite starting from infinitely lower numbers (Boscoreale went from 11 to 14 thousand visitors, for example). These are not problems related to the establishment of the Pompeii Park, nor to the current leadership, but it is striking that in recent years they have ended up getting worse, despite the creation of a unified institution and the availability of substantial funds. “Moving from the Superintendency to Pompeii Park has increased the hierarchy between sites,” one regular user explains. And indeed, even on the Park’s official website, pompeiisites.org, it is immensely easier for visitors to find information about their visit to the archaeological area of Pompeii than to every other site pertaining to the Park. The question then is, what is this new organization giving, and what have these 105 million given to the development of the area? It is unclear to the writer, and to those contacted to write this inquiry, what the concentration of media attention and visitors only on the archaeological area of Pompeii has brought to the territory.

Undoubtedly, however, among those who have gained a great deal from this exponential increase in visitors from 2.5 to 4 million in just a few years in Pompeii are the concessionaires of the additional services, who operate in the Park at very favorable rates, imposed when there were far fewer visitors twenty years ago, which have remained stable ever since, despite the change of contract, when change of contract there was: Opera Laboratori Fiorentini has been running ticketing and reception under an extension since 2004. In Pompeii, a curious fact, all services are contracted out to companies that are headquartered in the north-central part of the country. For catering and the cafeteria, Autogrill keeps 100 percent of the earnings for itself; for school tours, online presales, and the bookshop, respectively Coopculture, Ticketone, and Artem keep 90 percent of the revenue for themselves. What’s more, even the newly established Museum of Castellammare di Stabia, in the Reggia di Quisisana, was born with the online-only ticketing contracted out to Ticketone (heavily fined last Tuesday for abuse of dominant position): an unusual fact for a small local museum. This means that the money visitors spend at Pompeii’s excavations goes only in part to site maintenance and the salaries of workers employed there, and the move of online ticketing will further widen this vulnus.

“For 20 years we have been working for an oligopoly of cooperatives and private companies,” say workers organized in the COBAS-Private Labor union. With the increase in tourism and ticket sales, their salaries have not increased. They have been asking for months for a meeting with park management and internalization, “why is MiBACT thinking of hiring longtime unemployed through employment centers instead of solving our situation?” With the site closed, for months they were all on layoff, miserable, and constantly three or four months behind, but now things have not changed: they work in a few, for a few hours, while services are forcibly reduced precisely to save on them. There are more than a hundred workers employed in Pompeii as outsourcers and who have been working in Pompeii for decades, continuing to risk their jobs with each change of contract.

If there is no talk of stabilization for them, it has come instead for the Park’s technical secretariat and employees hired on a temporary basis in 2013, stabilized through an ad hoc competition announced in 2018. And here Pompeii finds itself equipped with what most Italian cultural sites do not have: enough internal technical staff. Why such a competition was planned specifically for Pompeii instead of for the entire public administration is unknown.

|

| The Castle of Lettere. Ph. Credit Tito Abbagnale |

|

| Palace of Quisisana. Ph. Credit |

|

| Antiquarium of Boscoreale. Ph. Credit |

|

| Antiquarium of Boscoreale. Ph. Credit |

Pompeii as an end or as a means?

270 years after its discovery, Pompeii continues to give so much to Italy and the world. This is beyond doubt. For Minister Franceschini today it is a “management model and an international reference point”(July 4, 2020) as well as a “virtuous example for recovery”(Dec. 26, 2020). However, Pompeii in recent years, moving radically away from the "state of siege" of 15 years ago (using an expression from Repubblica) has also taken a lot, from the unique and extraordinary site that it is: a lot of funds, a lot of media space, extraordinary hires and revenues related to mass tourism. Is a virtuous circle of research, enhancement, conservation and cooperation with the local area, as envisioned by the 105 million European investment, emerging in Pompeii, such as to justify the additional ministerial allocation of 50 million?

With eight out of nine Park sites blacked out in the media (also curiously: the RAI documentary Tonight in Pompeii was filmed in the entire Vesuvian area, for example, but without stating so in the title), four never opened, services contracted out to distant companies, a surrounding area that does not frequent the site, workers earning 7 euros an hour, large parts of the site excavated but not visitable, at great risk of degradation, the Park reopening the sites hierarchically, and the money from the Great Pompeii Project that has run out, it is legitimate to ask. The question then is: Can Pompeii give more? Does it give to the territory, to global archaeology and to Italian taxpayers more than it takes? At the end of this inquiry, it is the reflection we leave open.

The author of this article: Leonardo Bison

Dottore di ricerca in archeologia all'Università di Bristol (Regno Unito), collabora con Il Fatto Quotidiano ed è attivista dell'associazione Mi Riconosci.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.