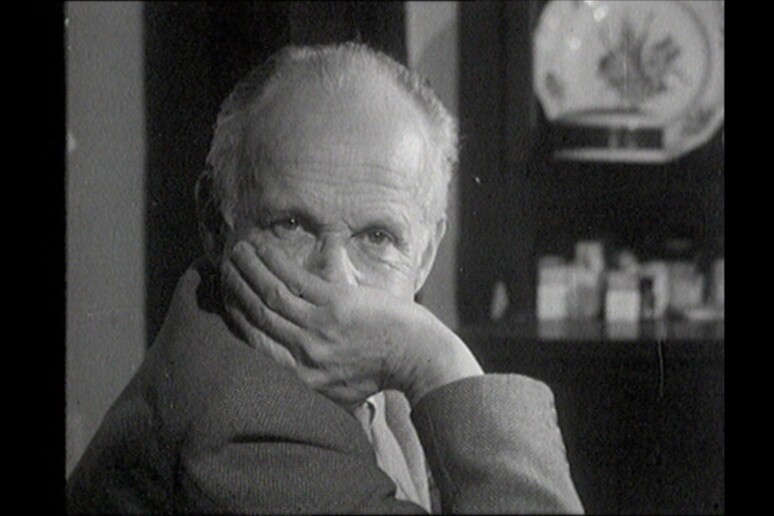

Undisputed master of modern photography, portraitist, narrator of the entire history of the twentieth century, called “the eye of the century,” theorist of the decisive instant, founder of the world’s most famous photo agency, Magnum: definitions are given of Henri Cartier-Bresson as diverse as the facets of his extraordinary path, but never before had we heard him called “the shady and touchy Norman photographer.”

After all, the pen is that of Giorgio Bocca, who in 1964 authored the documentary First Floor. Henri Cartier-Bresson and the World of Images made under the direction of Nelo Risi, and with Romeo Martinez, the man who from 1954 to 1964 was the architect of the revival of Camera magazine, the most important in Europe for the promotion of photography. An exceptional team for a document that has become a legend for photography enthusiasts and that today, after sixty years, emerges from the Rai Teche thanks to a project by Rai Cultura and Rai Teche entitled Dorian. Art Doesn’t Age that will bring it back to air next May 27 on Rai 5 and then on Rai Play.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, who died 20 years ago, left an indelible mark on the world of visual art through his ability to capture the essence of a moment with a unique skill and sensitivity. His was the era of Leicas, lightweight and silent cameras that allowed him to move with agility and capture scenes of everyday life with spontaneity and immediacy. He is distinguished by his ability to capture the decisive instant, that fleeting moment when all the visual elements combine perfectly to create a powerful and meaningful image.

“To photograph is to put the head, the eye and the heart on the same line of sight” is a statement of his that reflects the deep emotional connection the photographer sought to establish with the subjects of his images, conveying emotions and meanings beyond mere visual representation. Cartier-Bresson was not only a master of photographic technique; he was also a philosopher of the image, a silent storyteller of human lives and their complex interactions with the world around them. Pierre Gassmann, the only craftsman to whom Cartier-Bresson entrusted the printing of his photos says, “In Cartier Bresson’s art there is a whole historical and social situation that he knows how to express with a single photograph, whether the subject is an Indian beggar or the owner of a stable of racehorses in Ireland, it is not just the portrait of a guy.”

Theorist yes, but not prolific with words: his texts are few, short, interviews rare. Enthusiasts squeeze a few quotes from his biographers. He entrusted everything he had to say to his pictures. It is clear, then, what an exceptional event it is to be able to hear and see him. “To see” for what little he shows himself, staging an original minuet with the camera, from which he hides himself with stratagems, movements and choice of positions, from behind, behind a column or against the light, returning an ability to converse by images that goes beyond his own words: “The public will excuse me if I do not look him in the face, but the work I do forces me to preserve anonymity. It is a craft that is practiced point-blank, catching people off guard and where they are not allowed to show off.”

With Romeo Martinez he confronts, as equals, the role of photography, the responsibility of those who deal with images, and respect for the subject photographed. They talk about forgery and publicity, recounting an era that although sixty years distant from us, seems the same, “an era that violates nature and disintegrates the image,” adds the narrator.

Cartier-Bresson, recounts the great photographers of the twentieth century as friend and collaborator: André Kertesz, Man Ray and Robert Capa. Of the latter, who died a few years earlier during a reportage on the front lines of the Indochina War, he says; “Capa is the photographer who pays in person, in order to see reality as it is in dramatic and decisive moments, in order to free it from the false trappings of rhetoric. Capa represents the tough and generous breed of photographers who die. Of course one can die to photograph and still remain a bad photographer, but if one is like Capa also a very good photographer, one has the right to be considered as the best possible witnesses of difficult times.”

Together they helped redefine the concept of photojournalism, bringing the public’s attention to crucial social and political issues through emotionally powerful images. With him and David Seymour, he founded the Magnum photo agency in 1947, creating a new agency model that granted photographers creative control and copyright over their images. This approach helped redefine the role of the photographer as an independent visual storyteller and influenced the way images are produced, distributed, and consumed in the contemporary era.

Giorgio Bocca’s words take us to the theme of travel: “one travels not to see, but to photograph,” he says, which seems to be written today, “one is certain to have traveled to have enjoyed one’s vacation only when one possesses the images of travel and vacation. In this world where man lives among images often confusing reality with images.”

But Cartier-Bresson was a true traveler and an incredible storyteller of the world. As a correspondent for several magazines, he was one of the greatest witnesses of history between the 1930s and the 1960s: he photographed China in 1948 at the arrival of Mao Zedong and later in 1958, he was one of the last reporters to meet and photograph Gandhi, Mexico, Cuba, but also the Italian province of the early postwar period, of which his photos of Scanno are famous, which paved the way for a pilgrimage of many later photographers to the same places. Of his travels, he says, “First come the intellectual baggage, the preconceived ideas that one must have before going to the place, after that there is the surprise sharpened by curiosity. You need flair, to have an intuitive and spontaneous sensibility, then you need luck, backed by knowledge.”

But first it takes Cartier-Bresson’s recipe for photography: “For me it takes rigor, a certain control, a discipline, of spirit, a culture, finally intuition and sensitivity. It also takes a certain respect for the camera and its limitations. It takes eye, heart and brain.”

The author of this article: Silvia De Felice

Da venti anni si occupa di produzione di contenuti televisivi per Rai in ambito culturale e ha ideato Art Night, programma di documentari d'arte di Rai 5. L'arte e la cultura in tutte le sue forme la appassionano, ma tra le pagine di Finestre sull'Arte può confessare il suo debole per la fotografia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.