There is no virus for Donatello’s putti wiggling on the pulpit panels of Prato Cathedral: their festive dance has been going on for nearly six hundred years, heedless of any traversal, ready to mock wars and epidemics to the sound of trumpets and tambourines, indifferent to people’s stares, unwilling to any rule of “distancing,” a term to which some obtuse mind has thought of coupling the adjective “social,” creating one of the most devastating, despicable and rogue-like expressions ever to come out of human mouths. That the distancing is physical is evidenced, in a sleepy Prato awakening from the sad torpor of two and a half months of confinement, by the measures that everyone maintains from their neighbors, and that it is not social was evidenced by our desire to talk, to confront each other, to discuss even through virtual means, and now we see it in the eyes and smiles of the many people who, in order and little by little day by day, have begun to frequent the places of sociality again. It is a matter of respect: I stay away from you, because I do not want to infect you, and because you do not want to infect me. But not for a second would I dream (and it’s the same for you) of avoiding social contact.

That’s what, for sure, the many people taking laps on Via Mazzoni, from Piazza del Duomo to Piazza San Francesco and back, on this late May afternoon that feels like late July are thinking: stopping on street corners, lingering on a bench, having an aperitif at the bar. In Prato, as in so many other cities, the inhabitants are composed, they follow the rules, they do not crowd, they respect the queues at the entrance to the shops (and you, who see such orderly lines, wonder if it really needed a worldwide pandemic to teach Italians how to stand in line), they even greet each other by touching elbows. The museums are not entirely empty, as we would have expected: some people take advantage of the free admission that the City Council has arranged until June 3 to browse, still others enter to see an exhibition that they had not made it in time to visit before the government decreed the lockout of all the country’s institutions, there are those who simply wanted to see their city’s cultural sites again. The tourists are still not there: free movement within the regional borders was restored about ten days ago, but there is not all that much desire to move, on the contrary: there are many people who do not feel like it at all, to leave home.

|

| Donatello’s putti at the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Prato |

|

| Life in Prato from the windows of Palazzo Pretorio |

Prato is perhaps the most D’Annunzian of cities of silence. In Electra, the poet dedicates fourteen sonnets to it, an honor reserved only for this city, in which he had spent his adolescence: he was fascinated by the dense pages of its history, its ancient trades, the tabernacle of Mercatale ché today D’Annunzio would be horrified to know it is preserved in Palazzo Pretorio, the love between Filippo Lippi and Lucrezia Buti, portrayed by the painter in the Salome of the Stories of the Baptist that adorn the major chapel of the Duomo. Today, residents see the square on which the Cathedral stands mainly as a crossing point between the Porta al Serraglio station and the downtown streets. Especially in this season: it is all sunny, and the rays beating relentlessly on the pavement in this first bite of summer hardly entice people to pause. Those who are not from Prato, however, love its square shape, the duck fountain thrown in the middle there in the nineteenth century because it looks like a huge placeholder watched by the statue of Giuseppe Mazzoni on the opposite side, and that Cathedral that looks like a spaceship, white and green, tall and narrow, with those bizarre four-lobed salients, the clock in place of the rose window, and the unmistakable pulpit by Michelozzo that looks like a flying saucer stuck on the edge of the facade. For reasons unknown, Donatello decorated it with his dancing putti: today, however, the “pergamo rich with naked garlands” no longer stands “in the sun and wind like a great nest,” as the Vate saw it. To admire the originals, one must enter the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, the first stop on this first tour among the museums that have returned to the public after the end of confinement.

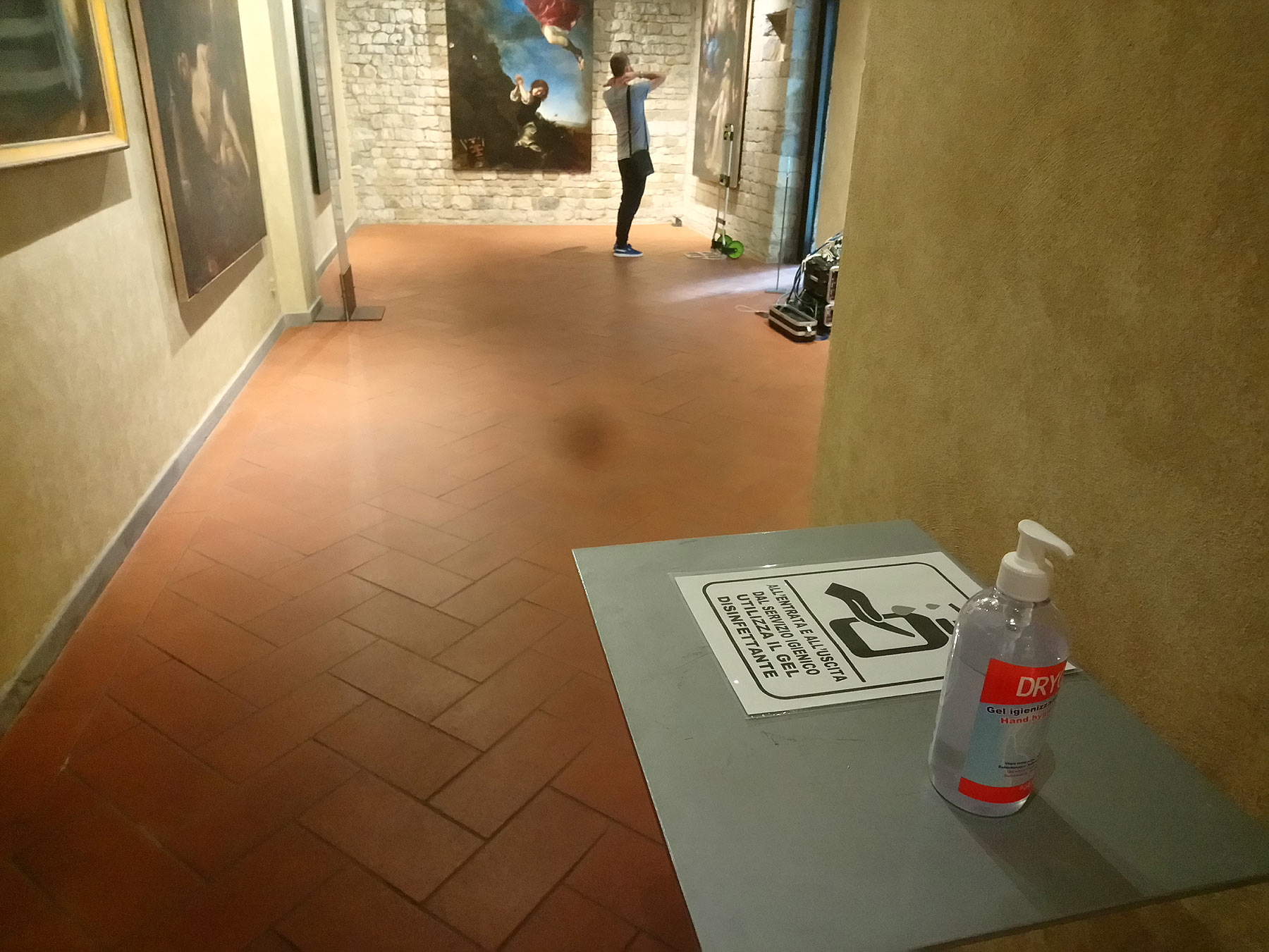

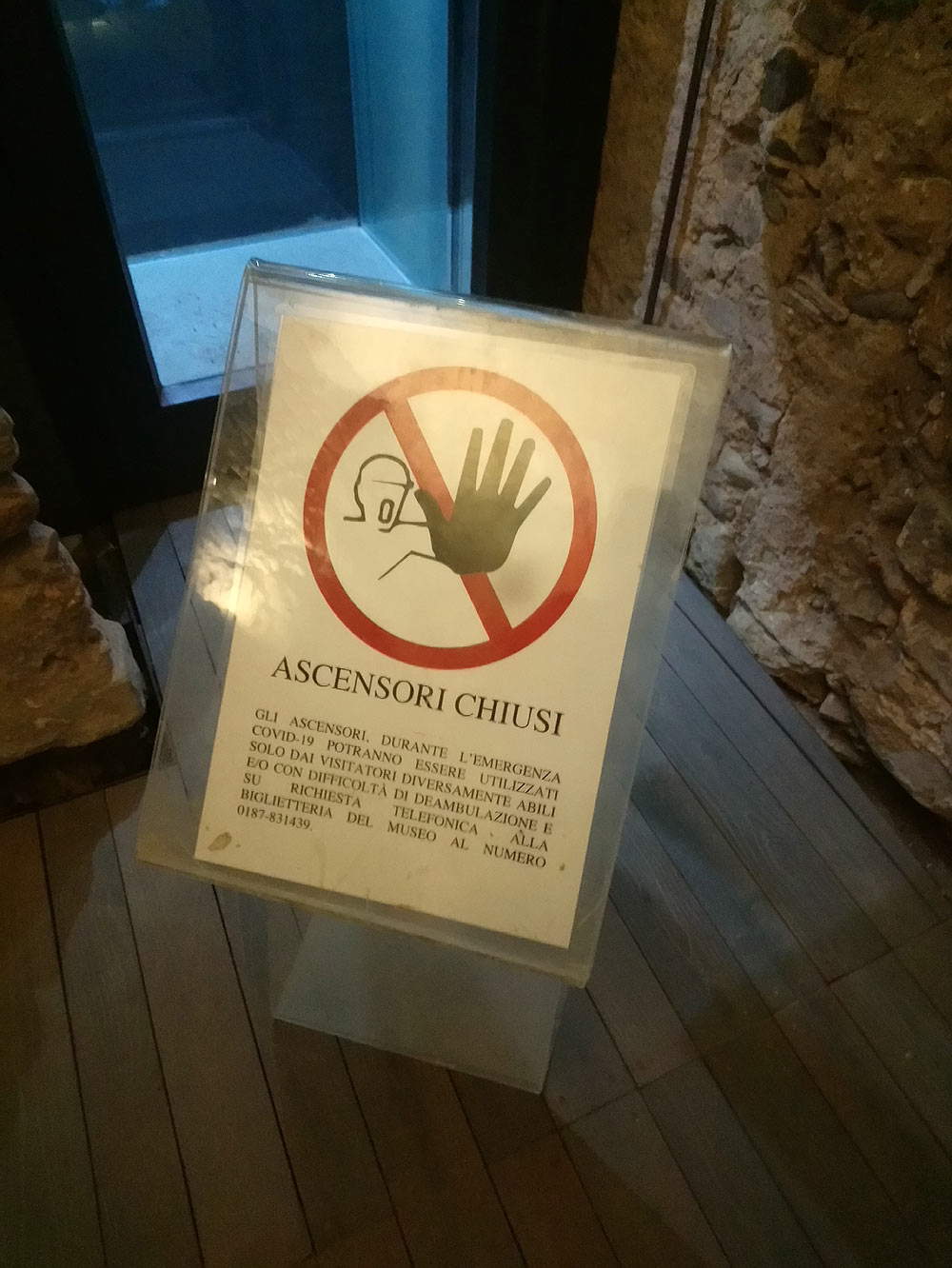

Visiting a museum, at this stage of timid exit from contagion containment measures, is a new experience, to be prepared more carefully than before: not all museums open at the usual times, there are some portions that remain closed, entrances are restricted, there are rules to follow (although, basically, they are always the same: obligation to keep your distance, obligation to wear a mask, obligation to sanitize your hands when entering and often also during the tour, or when using the services or when handling the objects on display in the book and souvenir selling areas). One notices right away that the museums are not the same as before: at the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, visitors are divided by the ticket clerks by means of a Plexiglas barrier, and then there is the ever-present one-way path, which here forces you to see the museum upside down. This is a condition that has existed since they opened the single ticket office under the bell tower of the Cathedral: before, however, it was at least granted the faculty to quickly walk through all the rooms to begin the tour, in chronological order, from where it once began, that is, from the small courtyard of the Bishop’s Palace, which has now become the obligatory exit. Now, on the contrary, the Covid forces one to make a journey back in time, starting from the frescoed vaults under the transept of the Cathedral: a corridor takes us to where the visit once ended, in the Romanesque cloister, from which one enters, first, the Hall of the Seventeenth Century. We then come to the Hall of the Pulpit, continue to the Halls of the Renaissance, pass through the archaeological excavation, and reach first the Hall of the Girdle, then the Hall of the Wall hangings, and finally the Hall of the Two and Three Hundreds, which once constituted the beginning of the visit, and is now the last room that welcomes us.

Impossible not to follow the rules, impossible not to understand where you are going, impossible to become infected. The whole museum is littered with bottles of hydroalcoholic gel (an attendant invites me to use it even as I am about to leave), it is filled with arrows showing the direction to follow, and with red signs urging us not to touch anything and to keep a distance of one meter: they are attached near the works, on doors, under windows, they even pop up on the illustration panels. It may be the obsessive presence of these signs, it may be the one-way paths, it may be that keeping the mask on, needless to hide it, is bothersome, it may be that this constant distancing and our all gagging around the halls is a disincentive to interaction, but the fact is that one undoubtedly feels less free. The company, however, is sparse: in an hour’s visit I pass three people, one lady, two peers in their 30s. There is no one else contemplating Donatello’s ignudi, nor do others linger beside me as I stare at Paolo Uccello’s blessed Jacopone in his sunken eyes; the room that houses Niccolò di Cecco del Mercia’s fourteenth-century slabs is empty; one admires in the most bewitching silence that masterpiece of eroticism that is Livio Mehus’s Communion of Saint Theresa. Many might even enjoy this solitude. It is like having the privilege of a private visit.

|

| Prato, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

|

| Prato, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

|

| Prato, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

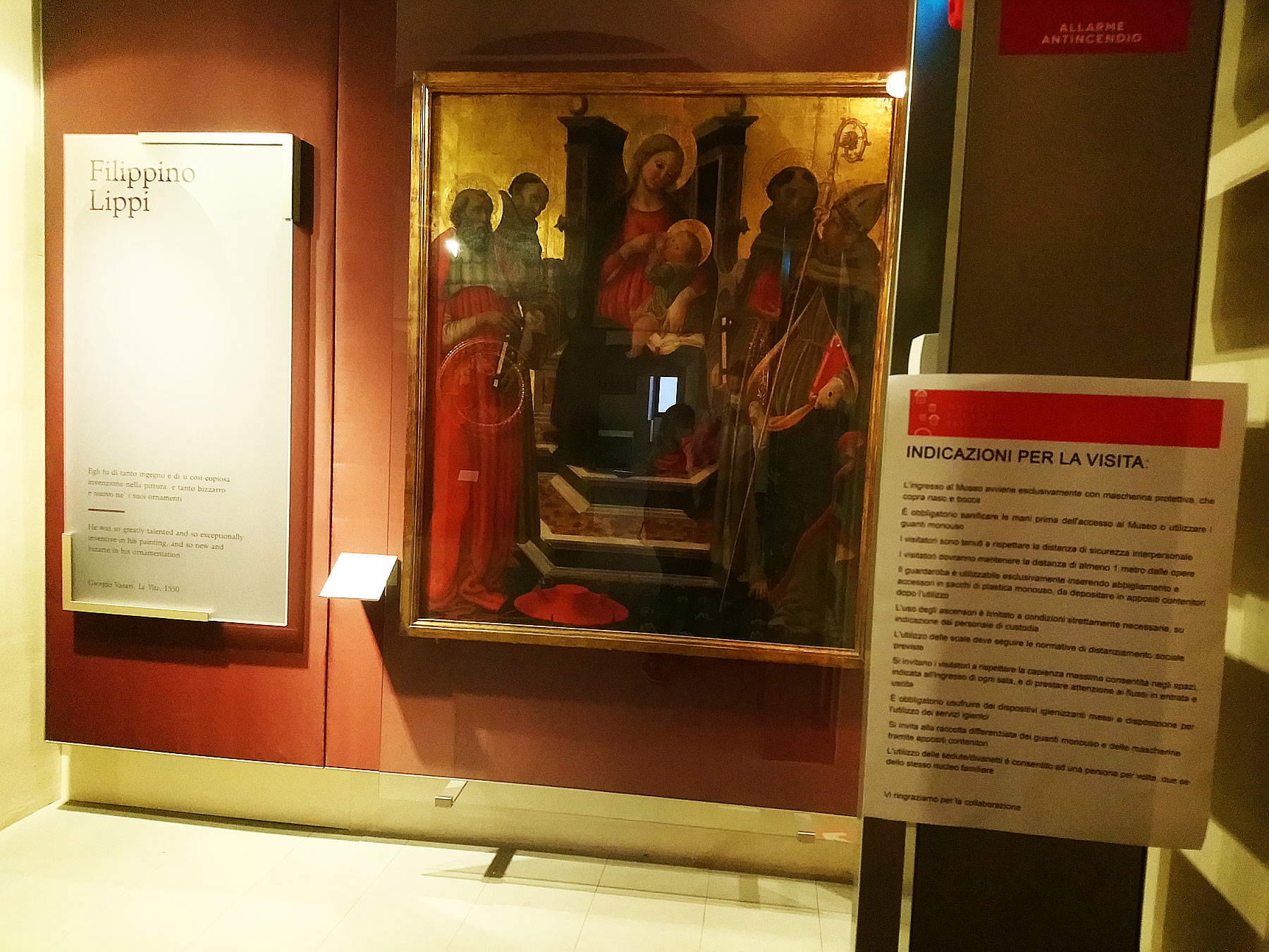

However, the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo is already little visited in its own right, and one could object by asserting that it is not difficult to walk through its halls in absolute quiet. The situation might be different at the Museo Civico di Palazzo Pretorio, where the long-awaited exhibition on the Caravaggesque painters in Prato’s collections has had to endure, like everyone else, two months of forced closure: and indeed, among these rooms, attendance is more plentiful. One enters by crossing the Piazza del Comune: the aperitif hour begins and the bar in front of the Palazzo is filled, especially with young people, but there is no crowding, the tables are spaced apart, and one strongly senses the desire to restart social life, even in the normal circumspection that naturally follows two difficult months. The museum, as is to be expected and obvious, is less populated than the bar in front of it. At the entrance one undergoes the ritual of measuring one’s body temperature, and here it would be interesting to make some small talk with those who think that a person with a fever of thirty-eight would want to visit a museum or that this tracking succeeds in detecting even those who, while contagious, have no symptoms: one is content, however, to know that this is also part of the show, one easily glosses over the few fractions of a second that the operation requires, the attendant who approaches me emphasizes, with his eyes narrowing to reveal a smile under his mask, that it is his duty, and one presents oneself in front of the transparent barricade of the ticket office to enter the museum.

The municipality has been very diligent: here, in the Praetorian Palace, each room is even preceded by a sign indicating how many people can enter. Ten, four, three, two, depending on the size. For the checkroom, one must use disposable bags. In the store, the use of plastic gloves is mandated (and it is not clear why: sanitizing gel is everywhere and the items for sale stand right in front of the ticket counter). On each floor, one or two receptionists follow the few visitors and carefully watch for compliance with anti-counterfeiting rules, but without nagging and rather showing benevolence in explaining the rules.

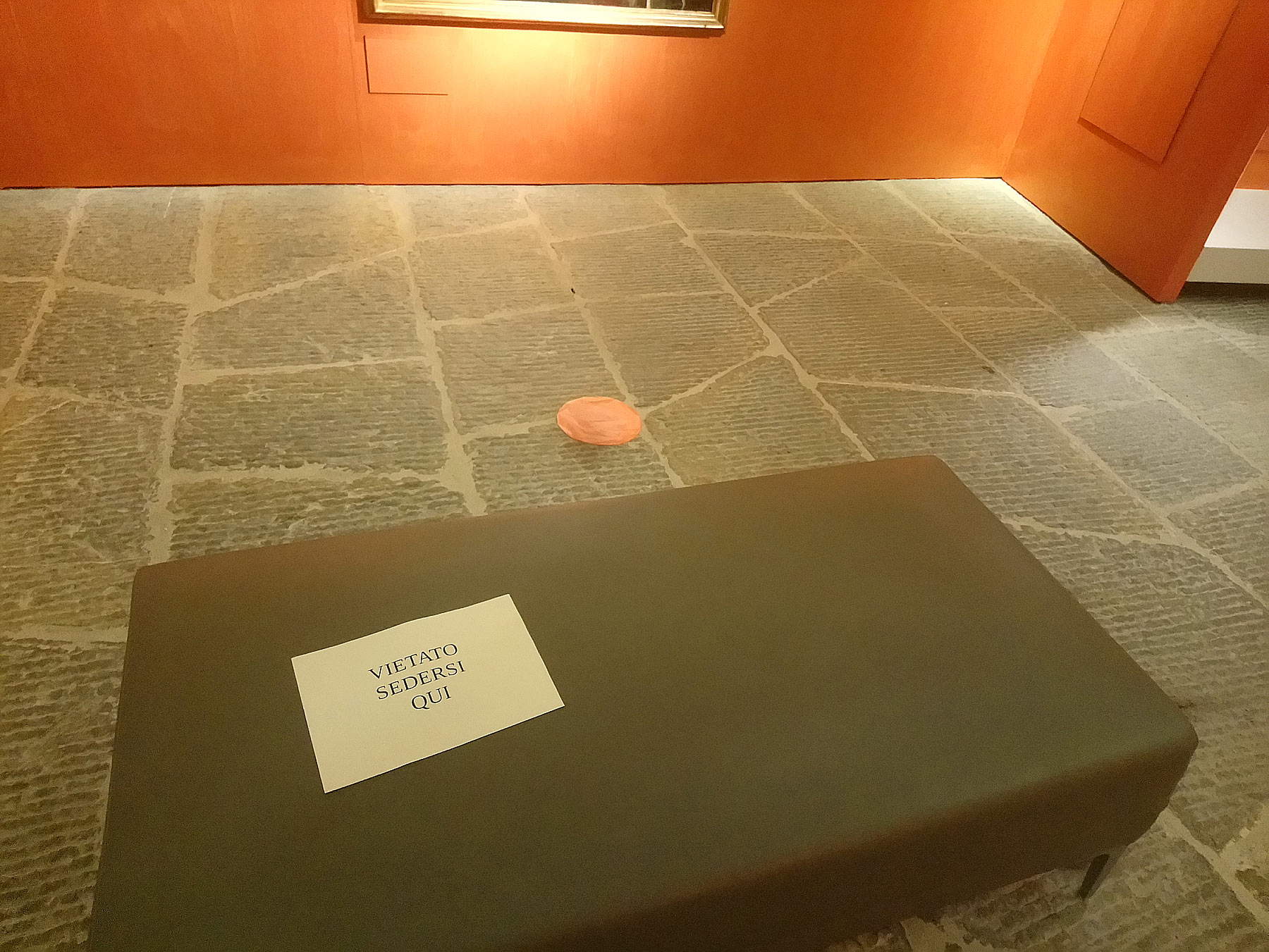

Today there are not so many people. They are all from Prato: there is the same lady I passed at the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, there is a couple of friends or colleagues in their fifties who evidently decided to visit the Praetorian Palace at the end of the workday, there are a couple of young people, there is a mother with two children. When different visitors are about to make contact in a room where the capacity is small, the attendants invite them to delay entering the room for a few moments. And one inevitably ends up staying a few minutes longer in the large central halls. There is one on each floor: the visit is lengthened, there is more time to admire the sumptuous late Gothic polyptychs by Lorenzo Monaco, Andrea di Giusto and the other greats of the 14th and 15th centuries, to learn about the history of the city through Filippo Lippi’s Madonna of the Girdle, and to delve into the story of the great 17th-century altarpieces of the Riblet donation, once the ornament of the chapel of Villa Spini at Peretola. The tabernacle that aroused the deep admiration of Gabriele D’Annunzio is in one of the small rooms on the second floor: here, too, you enter a few at a time. By contrast, the spacing is more relaxed on the top floor, where Bartolini’s plaster casts and early 20th-century works are housed, and in the rooms of the Caravaggio exhibition at Palazzo Pretorio and the De Vito Foundation: the rooms are larger and it is easier to keep measure from the others. There is also to be careful where to sit: in the benches placed in front of the masterpieces on display, some seats are occupied by sheets urging to leave a space of at least one meter free.

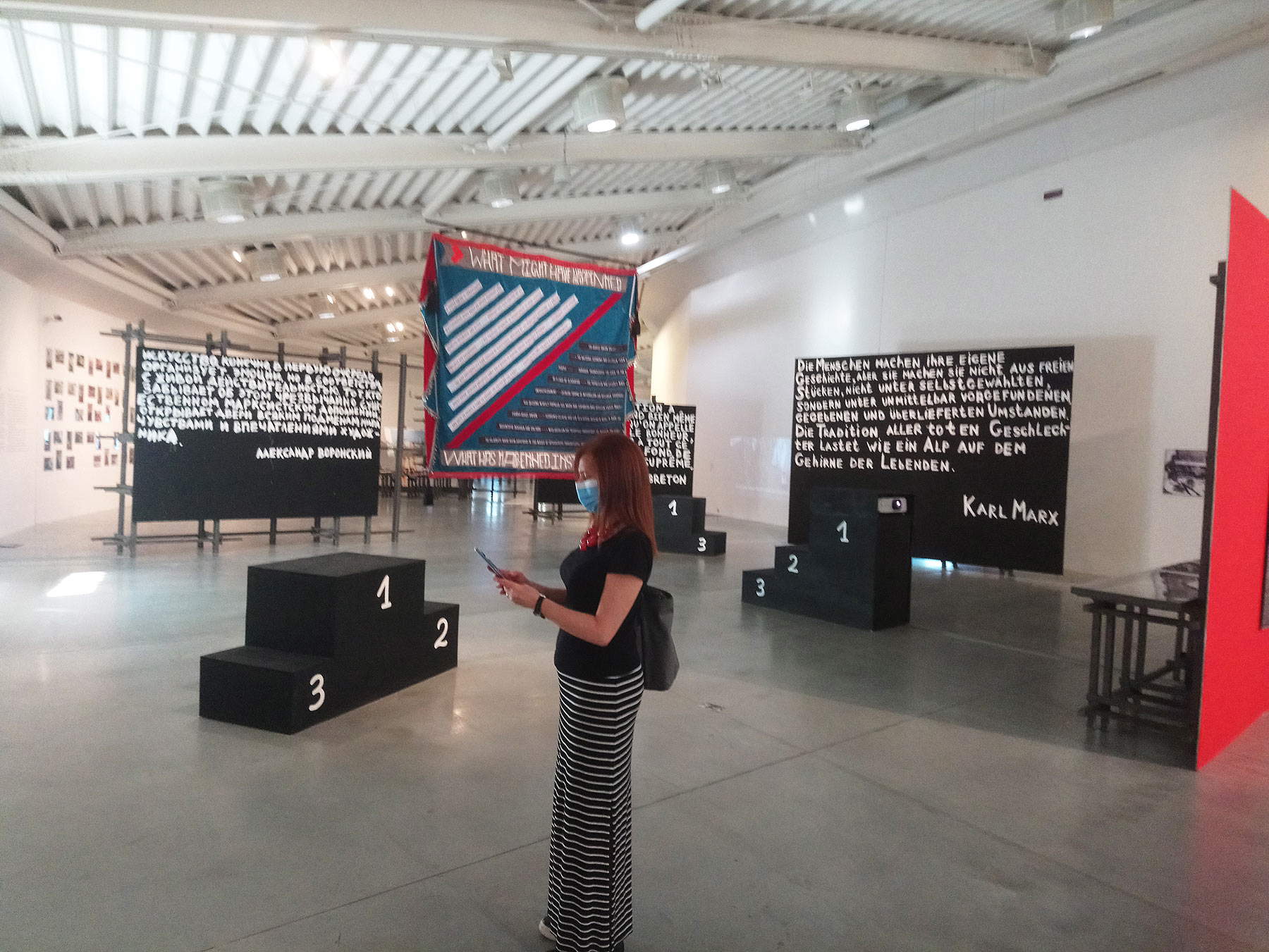

“In the first days of opening there were many visitors,” one of the attendants tells me. “We are not, of course, at the usual numbers, because there is a lack of tourists, and the people from Prato who are already familiar with the museum are not very likely to return at this time.” And this is despite the free admission, which may have encouraged a few more visitors, but was not decisive, nor did it create long lines at the entrance. What everyone is hoping is that this renewed way of experiencing the museum will also be a way to bring citizens closer to their heritage again, to attend museums in a different, more thoughtful and more participatory way. That’s what I begin to think when I move to the Pecci Center, which remains free until the end of July and until the last days of August hosts The Missing Planet, an exhibition on post-Soviet art that closes a trilogy begun in 1990. Here, the rooms are spacious, the distancing comes naturally, and the atmosphere is very relaxed. I enter together with a couple, everyone is measured for temperature, the two staff members, both very young, hand us flyers of the current exhibitions and explain in detail all the security measures the institute has taken. It is just over an hour before closing time, the museum is far from deserted, the average age is low: there are young people alone, a couple of couples, a family, there is a group of four friends, all harnessed as per the regulations to see, with an interest and curiosity that overcome even the harassing barrier of the mask and are perceived by the looks, gestures and words, this piece of the USSR transported to Tuscany, among constructivist reminiscences, gigantic installations that evoke Russia’s past through its symbols, ironic paintings, photographs of a world that was and another that would have liked to be.

|

| Prato, Civic Museum of Palazzo Pretorio |

|

| Prato, Museo Civico di Palazzo Pretorio |

|

| Prato, Museo Civico di Palazzo Pretorio |

|

| Prato, Museo Civico di Palazzo Pretorio |

|

| Prato, Civic Museum of Pretorio Palace |

|

| Prato, Civic Museum of Palazzo Pretorio |

|

| Prato, Pecci Centre |

|

| Prato, Pecci Centre |

|

| Prato, Pecci Center |

I decide to reserve the end of this first reconnaissance among museums for Lunigiana, which in the region has been among the areas most battered by the disease: in Pontremoli, on June 1, the Museum of Stele Statues at Piagnaro Castle reopened, albeit with reduced hours, and I resolve to visit there the next day, for Republic Day. The city streets are empty, businesses are closed: only a couple of bars in the two central squares are open. People here have preferred to flock to the countryside or to the mountains for long walks in the open air: in Lunigiana people shy away from any situation that might remind them of confinement, which has been harsh here because this area, a borderland between Emilia, Tuscany and Liguria where people speak a mixture of Ligurian and Emilian and where no one feels Tuscan, has paid the pathogen a high bill, with an incidence in relation to population among the highest in Italy, higher than in Milan, Turin, Monza, and all the provinces of the Veneto. It is hard to feel like going back to a closed place, especially if then at the museum, as in this period, there are no exhibitions or events can be organized. So I stay for an hour and a half alone in the halls, where the most important nucleus of the stele statues are kept, the strange and mysterious prehistoric sculptures of the Apuan Ligurians, perhaps erected as monuments to exalt the most eminent members of the communities, or perhaps to celebrate ancestors, or perhaps again to invoke a deity. Only two more visitors arrive as I am about to finish the path, which has been repurposed for the virus: the corridors and halls have all been bisected with chains and red and white sign posts to create two lanes of travel. Kind of like on the highway: it’s to prevent crossing and it’s to create a one-way route. If before you could move freely through the halls, now you have to follow the long two-color strip. Then the elevators were blocked, and not only the ones that transport visitors between the floors of the Castle: the ones leading from the city to the museum were also closed. Those who cannot face the ascent on foot must make reservations by calling the museum reasonably in advance. There is no reservation, but it is strongly recommended. Although attendance is low even today that it is a holiday.

Where, on the other hand, reservations are required is at the National Archaeological Museum in Luni: it is not even five kilometers from my home, but since I live in Tuscany and the museum is in Liguria, I have to wait until inter-regional circulation reopens to visit it. I take advantage of it on the first useful Saturday afternoon, in an unusually cool beginning of June: the air blowing in from the sea and heralding a storm does not prompt me to go to the beach, and I expect to find the Luni excavations packed. In fact, removed a family with mother, father and child, I am the only visitor for the last two hours of opening. The ticket clerk good-naturedly scolds me for not having booked access (I had not informed myself beforehand: a mistake that can be paid for by staying outside the door, in museums revolutionized by Covid), and it doesn’t matter that I am a journalist, the category seems to be given no exceptions. However, since the museum is empty at the moment, I am still allowed entry. The National Archaeological Museum in Luni is so far the only one that asks me to register personal data: it will be useful, in case of contagion, to understand who might have come into contact with whom. As I go through the formalities, I ask the attendant if there has been an enthusiastic response from the public in these first few days of opening (the museum reopened on June 2): they are moderately satisfied, because in the first week several dozen visitors wanted to return to the ruins of the ancient port city from which ships loaded with the white Apuan marbles that would bring luster to Rome sailed. The watchword in the City of the Moon and in Liguria’s archaeological parks is “safe culture”: the message the regional directorate wants to get across is that visiting a museum does not risk contagion, especially if it is outdoors, as here in Luni.

However, there is also to point out that the museum is largely closed: partly because the transfer of the collections to a new location, set up according to modern museological criteria, is in progress, and partly because not everything has been reopened, or it opens according to modalities and times to be verified at the ticket office. During my visit, for example, it is not possible to access the museum section of the domus and the amphitheater. It is said that a new course has begun for museums: perhaps, but certain is that the problems are the same as before. Indeed: at this stage they are exacerbated, since the presence of staff, which suffers from heavy shortages in most Italian museums, is essential to ensure public compliance. And where sight-seeing is not possible, one-way paths are invented to avoid encounters between visitors proceeding in opposite directions. Where even this is not possible, they close. And there are already many museums that close larger or smaller portions in the impossibility of “securing.” This is the locution suggested by the directives: and one wonders whether any fleeting encounter, of a few fractions of a second, between two people is really so harmful, and whether we are really dealing with a virus so powerful that it overcomes the obstacle of the mask to attack two passers-by at the very moment they accidentally cross each other, in the space of a quick moment. Or if the virus changes according to the institutes: at the Museum of Palazzo Pretorio in Prato, for example, the monumental staircase, the only way to reach the floors following the closure of the elevator, is not demarcated. Still, one would continue to get the impression that museums are very safe places even if there were not the unpleasant one-way forcing.

|

| Pontremoli, Museum of the Stele Statues of Lunigiana |

|

| Pontremoli, Museum of the Stele Statues of Lunigiana |

|

| Pontremoli, Museum of the Stele Statues of Lunigiana |

|

| Luni, National Archaeological Museum |

|

| Luni, National Archaeological Museum |

|

| Luni, National Archaeological Museum |

So many people these days have said or written that, from this experience, a new awareness about museums could be born, and new ways of visiting could spread, calmer, more thoughtful, more connected to the territory, less rushed and hurried, less driven by purely consumerist logic. Undoubtedly, without the crush, visiting a museum is much more enjoyable. Seeing it frequented only by locals is a beautiful and fulfilling experience because there is a stronger sense of community, but I fear we will only be able to take advantage of that, likely, in these weeks. But I also believe that the underlying truth goes back the other way, as if upside down: certainly not because there is no need for a new way of conceiving museum visitation, but because this calm, this relaxation, this slowness in going through museums is the result of obligations and impositions and does not come from a real and thoughtful discussion of the problem, which has not even begun. On the contrary: for much politics, museums are not yet necessary cultural bastions, essential presides for the social and economic progress of their communities, fundamental places of discussion that admit and promote confrontation and diversity, indispensable centers for the development of critical thinking, but still remain the handmaidens of tourism. Only when politics sees museums in this way, only when revitalization plans manage to contemplate the multiple roles of museums, only when a profound revision of our concept of “museum” is initiated, then yes, we will really be able to speak of a renewed awareness.

For now, we can be content to visit a museum without taking any chances. At most, we can ask that we avoid talking about the “new normal”: a shrill, detestable, hateful and repugnant expression. There is nothing normal about not being able to see one’s neighbor’s lips concealed by a muzzle; it is not normal to have to stand at a distance from others by forgoing a handshake, a hug, or any physical contact, since contact is one of the oldest and most intimate ways we have of communicating; it is not normal to suspend indefinitely that sociality made up of meetings in places where one is squeezed in, it is not normal to think of Plexiglas as the solution for everything, it is not normal to think of the tide of plastic we are producing and consuming to cope with the state of things, it is not normal to consider life in its bare biological dimension, it is not normal to consider that health securitarianism that has reached the paroxysms we have all witnessed, such as pursuing solitary physical activity with great deployment of effort, and which could return at any moment. Instead, it is fair and honest to say that we are still in an emergency, and that we are accepting and following these rules with a great sense of responsibility not because it is normal, but because we understand that we are in a situation that is still exceptional, and we want to protect ourselves and others: some people may not like to hear the word emergency again, but it responds better to the state of things and does not give us the idea that this emergency may in the future become a permanent state of exception.

It goes without saying, however, that we are all happy to have returned to take back almost all the small daily freedoms, the lack of which we felt during the oppressive weeks of confinement. At the beginning of May, Claudio Magris recalled that for many the best hours of the day were those of the authorized walks to the workplace, especially if the distance was great, but also that now the time has come to reflect on the fact that what we have before us will have to contemn life as a whole, and that a life humiliated in its most basic needs is a misfortune of no lesser proportions than a serious illness. Wanting to be rhetorical, it could be said that reconnecting more closely with culture, in whatever form it may manifest itself (museums, exhibitions, books, films, music, experiences of any kind) might also mean a more careful consideration of the problems that await us in the future. Remembering that human beings are not made not to be open to others. This was reminded, in the first of his Microcosms, again by Claudio Magris. “For a long time one has done nothing but close the doors, it is a real tic; for a while one draws one’s breath, then anxiety grips one’s heart again and one would like to bolt everything up, even the windows, only to realize that in this way the air is lacking and that the migraine, in that suffocation, hammers one’s temples more and more, little by little one ends up hearing only the sound of one’s own headache.”

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.