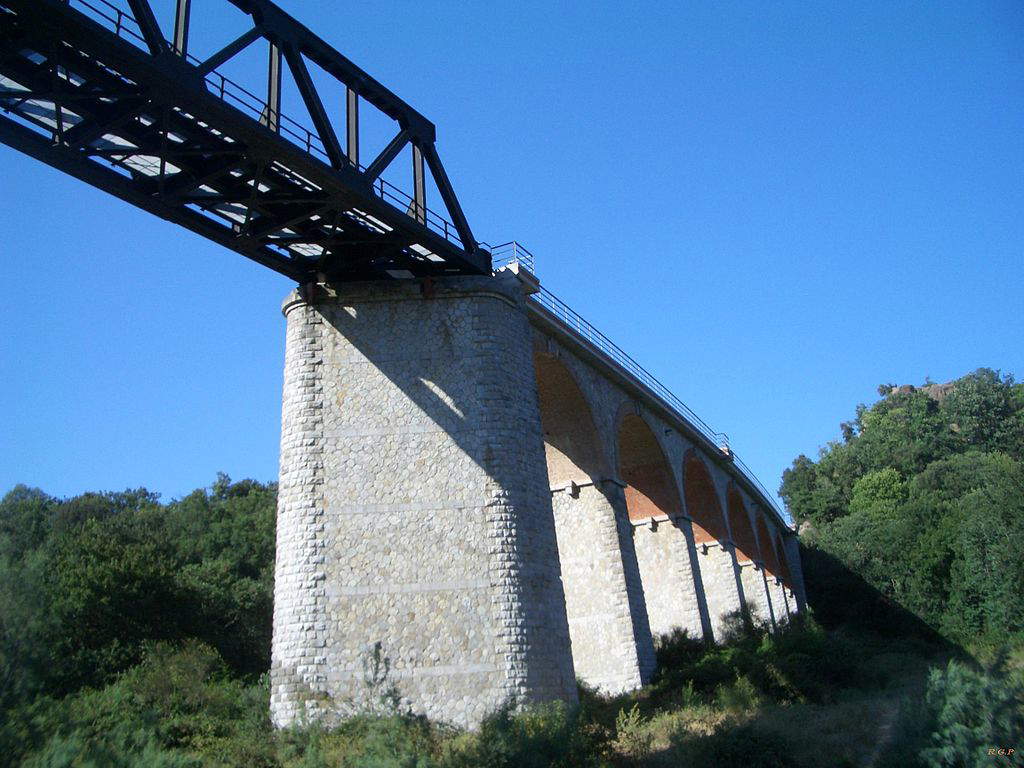

It was June 4, 1944 when, four months after the Anzio landings, the Allies began arriving in Rome to free the capital from the Nazi grip. During the dark years of World War II, the Capranica-Civitavecchia-Orte railroad continued its operations undaunted, although it was limited to a reduced flow of passengers and freight. The conflict involved the railroad in wartime actions by the Allies aimed at destroying bridges in order to hinder the retreat of German troops. The bridge that spanned the Mignone River suffered a devastating aerial bombardment that compromised one of the masonry arches, making it impossible for trains to pass through until 1947. From the 1950s the railways began to consider it as a marginal sector, reducing the number of daily runs and maintenance activities. And so, on the night of January 8, 1961, after three days of incessant rains, a landslide crossed the Civitavecchia-Capranica section, causing ten meters of soil destruction. From here, many were the proposals for a restoration that was never carried out.

Today, we can only imagine that journey, or retrace it along a very popular trekking route, to be traveled on foot or on a mountain bike, which runs along the route of the old railroad and has become something of a hiking classic for locals. We can imagine boarding a tired train, traveling with difficulty and exploring the world from the window, admiring centuries-old olive trees and getting off from time to time. The railway ran through one of the richest areas from an archaeological point of view in the entire region of Latium. The most significant historical evidence belongs to the Etruscan civilization, but there are also traces of life during the Roman and medieval eras. You will discover, first, the Scaglia: an Etruscan necropolis dating from the 6th-5th centuries B.C. in which simple single-chamber burial tombs show structures fashioned to house beds and funerary objects.

Continuing for another fifteen kilometers we would arrive at Palano - Ripa Maiale. The Palano area has revealed a rich collection of artifacts dating back to the Middle Paleolithic, testifying to the presence of ancient populations between 200,000 and 35,000 years ago. These artifacts, preserved mainly at the Allumiere Civic Museum, include tools made by chipping siliceous limestone, and near Ripa Maiale, one can observe cave shelters and under rock shelters that were probably adapted and used by archaic populations. It will then open up, to the traveler’s gaze, Cencelle. A town, this one, of relevant importance, founded by Pope Leo IV in 853 to offer refuge to the inhabitants who fled Centumcellae after the Saracen invasion. Situated on the top of a strategic hill, it dominated the Mignone valley to the sea. It was probably an inhabited center even in Roman times. In 1200, it had about 800 inhabitants and relied on agriculture, animal husbandry and to a small extent fishing. However, the construction of the Civitavecchia - Capranica - Orte railway in 1928 destroyed one of its churches and left signs of its fortified towers and walls.

Pre-Unitarian Italy had a railway history characterized by significant delays compared to industrialized nations such as France and England. The Unstoppable Industrial Revolution exerted pressure for accelerated modernization of states, promoting the adoption of liberal structures and technological progress. However, the railway network, a tangible symbol of this progress, remained largely confined to the former Lombardy-Venetia Kingdom when the Unification of Italy was achieved. A close look at the political and economic landscape of the time reveals the contrast between Risorgimento ideals and conservative forces, represented in particular by the Papal States, and in this context, the railroad not only symbolized technological progress but also embodied the ideals of national unity and independence, key elements of the Risorgimento movement. As early as 1846, proposals for the establishment of a railroad network in the ecclesiastical state had been submitted to Pope Gregory XVI, with the aim of connecting important cities such as Rome and Civitavecchia. However, these proposals met with hostility from conservative clergy, who saw modernization as a threat to their traditions and power.

Things changed significantly with the ascension to the papacy of Pius IX in 1849. His willingness to explore new frontiers and embrace change was manifested when he accepted King Ferdinand II of Bourbon’s invitation to personally experience the train on the Naples-Portici line. This symbolic gesture not only marked a turning point in relations between the Church and technological progress, but also laid the groundwork for a significant change in attitudes toward the railroad as an engine of modernization. Pius IX’s trip aboard the train and his visit to the locomotive factory at Pietrarsa represented a bold step toward the adoption of railway technology, and the event marked the beginning of a process of slow but necessary open-mindedness and adaptation to the demands of modernity, paving the way for new opportunities for connection, economic development and social transformation.

It was in this context, in 1870, that the idea was born to build a transversal line that would connect the ports of Civitavecchia and Ancona, passing through Terni. The project that saw its actual birth, however, was not presented until 1907 by Valentino Peggion and Nicola Petrucci with the help of engineer Carlo Carega, and the line would have grafted onto the pre-existing Capranica- Ronciglione line. Construction work on the Civitavecchia - Capranica - Orte began in 1922 and from the very beginning there were endless problems about the accidentality and quality of the terrain to be crossed, which led to its closure after World War II.

It was noticed from its inauguration in 1929 that this would not be a railway line destined for greatness, and it was precisely because of the terrain so uneven and clayey that it was preferred to handle only local passenger and freight traffic, but in 1935, given the absence of travelers, it was decided to discontinue First Class travel. By 1939, the flow of passengers was mainly delineated as a fabric of rural commuting, arising from the railroad’s inescapable need to cross and join isolated regions where the lack of roads was an undeniable fact. It took a full 10 years after the operational start of the railway line for work to finally get underway to give shape to the much-needed electrification project, which had already been envisioned in the 1917 alternative plan. However, the implementation of these works resulted only in the creation of a high-voltage power line connecting Civitavecchia to Orte. This power line, even today, runs parallel and often a short distance from the railroad, along with local facilities designed to accommodate the electrical substations at Monteromano and Capranica. The aspiration for modern rail electrification, unfortunately, resulted in a limited reality that only highlighted the challenges and complexities involved in implementing an advanced and sustainable transportation system.

Following its intricate historical patterns will now make it easier to continue the journey and get back on that train. We could imagine getting off at Allumiere station where, nestled in the woods, we would find a small hermitage. It is the oldest sanctuary in the Tolfa Mountains, built on an earlier Roman villa. Tradition holds that St. Augustine stayed here for a long time during the period when he composed his second Rule and began writing “De Trinitate.”

A little further on our route will open up La Farnesiana, a hamlet developed around a water mill built in the 16th century in the Campaccio valley. Along with a small church, it was inhabited by religious men who also ran the mill. In 1754, the hamlet and mill were abandoned and later became a farm to produce grain and raise livestock for miners working in the nearby quarries. The church of Santa Maria della Farnesiana was built in 1836 and then dedicated to the Immaculate Conception in 1877. The village has retained its original appearance, but the church is now in ruins and in danger of collapse.

One will have to continue for another long kilometers, precisely 23 from the first station of departure, to find oneself in Luni sul Mignone. Located on a tuffaceous stronghold overlooking the Mignone River, this site has evidence dating back to the Neolithic and continuing into the Bronze Age. The settlement was abandoned around 1300 because of the plague. Luni was the subject of systematic excavations by the Swedish Institute in the 1960s and includes finds such as a hut carved into the tuff and ancient graffiti on a cave. It also offers an extraordinary panoramic view of the Mignone River valley. Further on we would discover, Blera, which began as an Etruscan town and became a Roman municipality that played a very important role between Longobard Tuscia and Rome. It continued to have relevance in the Middle Ages, despite a slight loss of importance. Here stands, majestically, the Roman Devil’s Bridge, which crossed the Via Clodia over the Biedano ditch. A monument, this one, dating back 2,500 years and built of dry-walled peperino blocks, and it is precisely because of this millennia-old solidity that it would seem to have been built by the devil himself.

Climbing back into our now friendly wagon, we would soon find ourselves in Barbarano Romano, which has a medieval settlement enclosed between the Biedano ditch and one of its tributaries and retains its original urban appearance, while an ancient fortification protects its undefended side. Here our journey, among different histories and places connected thanks to this stretch of railroad ends, the explorer may think of actually carrying it out, walking along the trail.

|

| Along the former Capranica-Civitavecchia railway, among archaeological sites and abandoned stations |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.