Ninth stage of our journey to discover animals and fantastic places in Italian museums: let’s find out today what is hidden in Umbria. The project is led by Finestre Sull’Arte in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture to bring the public to know and attend museums, safe places suitable for everyone, from a different point of view than usual. Enjoy your trip!

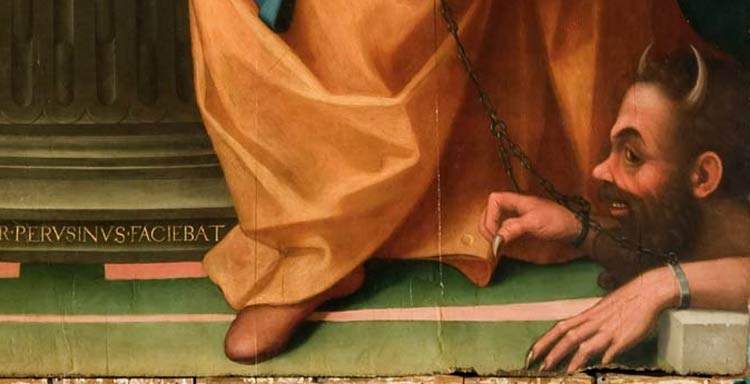

The devil, depicted as a satyr with an eerie expression and long claws, now lies harmless and chained: he has in fact been defeated by Saint Juliana, the titular saint of the church for whom this altarpiece by Domenico Alfani, now in the collection of the National Gallery of Umbria, was intended when it was painted in 1532. The panel, which depicts the Madonna and Child together with Saints John the Baptist and Juliana, with two little angels in the act of adoration, remained in the church of Santa Giuliana in Perugia until 1812, the time of the Napoleonic suppressions: that year it was taken to Rome and was able to return to Umbira with the restoration, in 1815. It was finally moved to the gallery in 1863. Legend has it that Juliana of Nicomedia, a martyred saint who lived in third-century AD Turkey, was betrothed to a pagan named Eulogius. She, steadfast in her Christian faith, refused to marry him unless he converted to Christianity. Her father, also a pagan, would not comply with his daughter’s demands and had her imprisoned with the intention of making her renounce her faith. Hagiography relates that while Juliana was in prison, the devil tried to tempt her, and she repulsed him by beating him with her chains: hence the reason for this depiction. Despite her imprisonment, Giuliana did not deny her faith, and for this reason she had to suffer martyrdom, by beheading.

The griffin, it is well known, is the symbolic animal of Perugia: a legendary winged creature with the body of a lion and the head of an eagle, the griffin stands out, white on a red field, in the city’s coat of arms. And it is griffins in the company of lions that are seen in this bronze sculpture, made in the last two decades of the thirteenth century, perhaps by a sculptor known as “Rubeus,” i.e., “Red” (although critics are debating the author of the sculpture): the griffin, as mentioned, was the symbol of Perugia, while the lion was the symbol of the Guelph side (Perugia was a Guelph city). This group was probably employed on the top of the Fontana Maggiore, which is located right in front of the Palazzo dei Priori that houses the National Gallery of Umbria, where the work is preserved (and where, at the entrance, we find just a griffin and a lion): perhaps it was an automaton designed to give life to water games and gushes, but given the very high quality of the artifact it is also possible that it was employed as a decoration of a pilo, a flagpole. In any case, Giorgio Vasari and other witnesses who lived between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries testify that at that time the bronze group had a hydraulic function, but we do not know if that was its origin.

The Bufalini Castle is located in San Giustino (Perugia) and its present form dates back to the late 15th century, when the new owner, Niccolò di Manno Bufalini, who came into possession in 1487 of the land on which stood an ancient fortress that had been destroyed shortly before by the Florentines, took charge of the reconstruction, and called the architect Mariano Savelli to carry out the work. The Bufalini family held ownership for centuries, and the descendants of Niccolò di Manno, in time, transformed the castle into a sumptuous frescoed residence. Cristofano Gherardi known as the Doceno (Sansepolcro, 1508 - 1556) is responsible for the frescoes in the Hall of the Gods, with stories inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses that so inspired painters between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries: a way of giving form, on the walls of the hall, to fantastic stories that unfold in the panels beneath the lunettes. However, fantastic creatures also populate the ceiling: it is in fact entirely decorated with grotesques, with animals of all kinds, real or fictional, that make up one of the most original decorations in all of Umbria.

Mermaids abound in Etruscan art, but those who think of fabulous half-woman, half-fish creatures would be wrong: the mermaid in the National Archaeological Museum of Umbria is that of Greek myth, that is, a creature with the body of a bird and the face of a woman. The mermaid that spread more easily in the collective imagination, the creature with the tail of a fish precisely, became established only from the 8th-9th centuries AD, thanks mainly to a bestiary known as Liber Monstrorum. The mermaid in the National Archaeological Museum is a small bronze sculpture that decorated the lid of a situla, also made of bronze: a “situla” refers to a particular type of vase, in use by various ancient civilizations, which was used to hold water or wine and was used mainly in the religious sphere, for ritual purposes. The siren in question was found in a necropolis located near the monastery of Santa Caterina, along the road to the hill of Monte Ripido, just above Perugia.

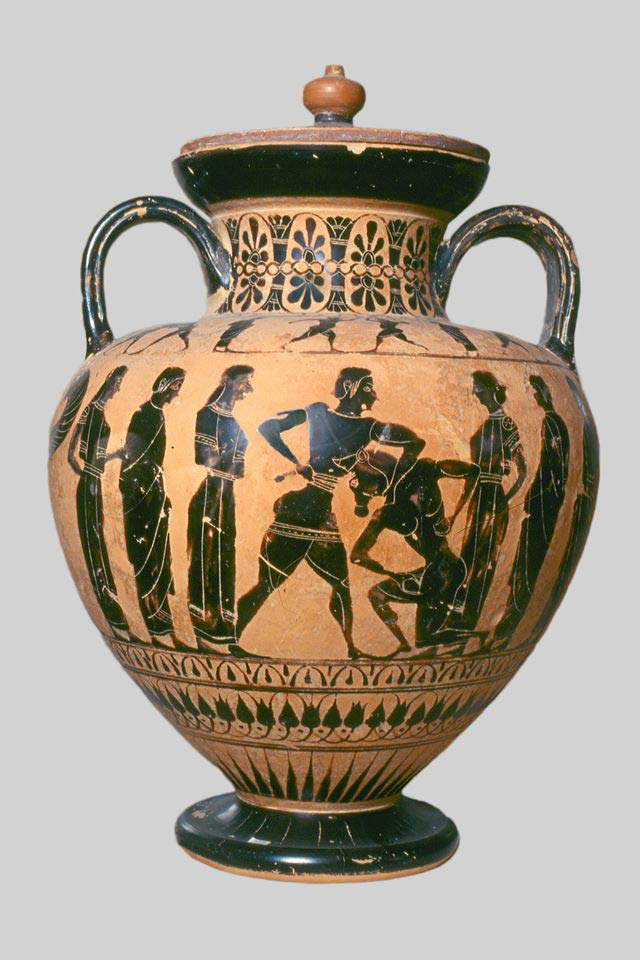

Legend has it that the queen of Crete, Pasiphae, the wife of King Minos, fell madly in love with a bull sent by Poseidon to Minos to be sacrificed in his honor: it was the sea god’s revenge on the king, who considered the animal too beautiful to sacrifice and therefore decided to keep it and offer another beast to the god. Thus, Poseidon, in order to punish Minos drove Pasiphae mad with love for the bull, so much so that she united with the animal and from this bestial union a monster was born, the Minotaur, half man and half bull. Minos had the dangerous animal imprisoned in a Labyrinth designed by Daedalus: however, the fierce creature required a meal of seven girls and seven boys each year, a tribute that Minos demanded from Athens. One year, the young men arriving at Knossos, the capital of Minos’s kingdom, included Theseus, the hero who would later slay the monster: the black-figure Attic amphora in the National Archaeological Museum of Umbria depicts precisely the moment when Theseus, watched by the other young men who were to end up in the beast’s jaws, grabs the minotaur by the neck and prepares to deal him the fatal blow. The work comes from a settlement, in the area of Marsciano and more specifically in the locality of San Valentino, inhabited since the third millennium before Christ and where there was an Etruscan settlement in ancient times.

This object is a kyathos, that is, an ancient vessel with a large ring handle, which served as a drawing bowl. And it is, in particular, a bucchero, that is, a pottery obtained through a process that made it black and shiny: bucchero was particularly widespread in Etruria, especially in the Chiusi area, where this kyathos with gorgon comes from. Or rather: with the gorgoneion, or Gorgon’s head, which has the appearance of a monster with snake hair and huge, frightening eyes, since gorgons were able to petrify with their gaze. In the ancient world, gorgonians were also reproduced on everyday objects, such as a kyathos in fact, in an apotropaic function, that is, to ward off evil: the face of the jellyfish assumed, in essence, a defensive role. The gorgoneion in question, the museum explains, is a Gorgone/pothniatheron (“lady of the animals”): the apotropaic value is here added to “the concept of dominion over nature and the reference to the birth, from the severed head, of Pegasus and his brother, the giant Chrysochor (conceived in union with Poseidon), in this case replaced by a second horse.”

We do not know the author of this winged ox, a 13th-century marble sculpture that comes from the Cathedral of Spoleto (and specifically from the right buttress) and is now preserved pressa the National Museum of the Duchy of Spoleto, located on the premises of the Albornoz Fortress overlooking the city. In medieval churches it was common to encounter sculptures depicting the symbols of the four evangelists, and Spoleto Cathedral is no exception: the winged ox is symbolic of St. Luke. In fact, the Gospel of Luke opens with the episode of the announcement to Zechariah, husband of St. Elizabeth and father of John the Baptist, with the angel arriving to bring him the news of his wife’s impending pregnancy. Zechariah was the priest of the temple in Jerusalem, and St. Luke’s ox therefore recalls the bulls that were sacrificed on the altars. But the ox was also an animal endowed with great patience, a sentiment often associated with St. Luke, who is also the patron saint of artists. And creating works of art, it is known, takes a lot of patience.

This colored dragon, now housed at the Orvieto Archaeological Museum, is a fragment of the decoration of Orvieto’s ancient Etruscan temple, called “del Belvedere” because of its location in the center of the city on the cliff, near the Pozzo di San Patrizio and in a panoramic position. Of the temple, the staircase and some portions of the foundations are visible in situ, and also the ground plan can be clearly distinguished. Everything else was lost, but some decorative fragments, such as the dragon, were saved and are preserved in museums in the area. The temple was discovered in 1828 and was dedicated to the god Tinia, the Jupiter of the Romans. The dragon in question follows the typical Etruscan representation of this fantastic animal: a kind of snake with a sinuous body and a very elongated snout, almost as if it had a beak.

It’s really appropriate to call it. Madonna del Soccorso: the singular panel by Tiberio d’Assisi (Tiberio Ranieri di Diotallevi; Assisi, c. 1470 - 1524), one of the main protagonists of the Umbrian Renaissance, depicts a Madonna about to come down with a club on the devil, represented as a hideous being with a goat’s face, bat-like wings, a snake knotted at the waist like a belt and equine legs, caught as he is trying to kidnap a blond child, visibly frightened. The Virgin comes to the rescue, pleaded by the prayers of the young mother on the left, ready to hurl her staff at the evil one. The iconography has many precedents, especially in central Italy where stories of the Madonna interceding to deliver possessed children from the devil abounded in the Middle Ages, but the vernacular and almost grotesque way in which Tiberio d’Assisi resolves it is very peculiar. The work, painted around 1510, was commissioned by a certain Griseida di ser Bastiano (it is the inscription running along the lower border that reveals the name of the commissioner), and for a time was attributed to Francesco Melanzio. The work is now kept at the Museum of St. Francis in Montefalco.

One of the most fantastic places in Umbria is definitely the Cosmic Magn et of Foligno: this is the name of the work created in 1988 by Gino De Dominicis (Ancona, 1947 - Rome, 1998) and preserved in the Italian Center for Contemporary Art whose headquarters is in the former church of the Holy Trinity. The Cosmic Magnet is a huge human skeleton (24 meters long, 9 meters wide and almost 4 meters high) that occupies the entire length of the former church building: it is lying down, and its peculiarity lies in the fact that instead of a nose it has a kind of long bird beak. In his right hand he holds a long golden rod: the key to the interpretation is precisely the golden rod, which represents the means that connects the skeleton with the cosmos (and hence the name by which the work is known). A one-of-a-kind work made of fiberglass, iron, and polystyrene, created by the artist in secret, it is not known for what reasons De Dominicis made it, but it certainly contributes to the fantastic nature of this place!

|

| Animals and fantastic places in Italy's museums: Umbria |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.