When he moved to Italy after World War II, landscape architect Russell Page (Tattershall, 1906 - London, 1985) found, in the gardens he had the opportunity to visit, an old-fashioned and unfashionable country. At a time when labor in large gardens was excessively expensive, a tendency to create gardens with a nineteenth-century romantic character, enhanced by seasonal plantings, had prevailed. Botanical knowledge, moreover, was rather limited, and decisions about what plants to grow rested primarily with the home gardener, and so the figure of the landscape gardener was virtually unknown, making the impact that a sophisticated and knowledgeable gardener like Page could have in this context all the more significant. His presence was, therefore, crucial for those who could afford to create gardens of the highest standard.

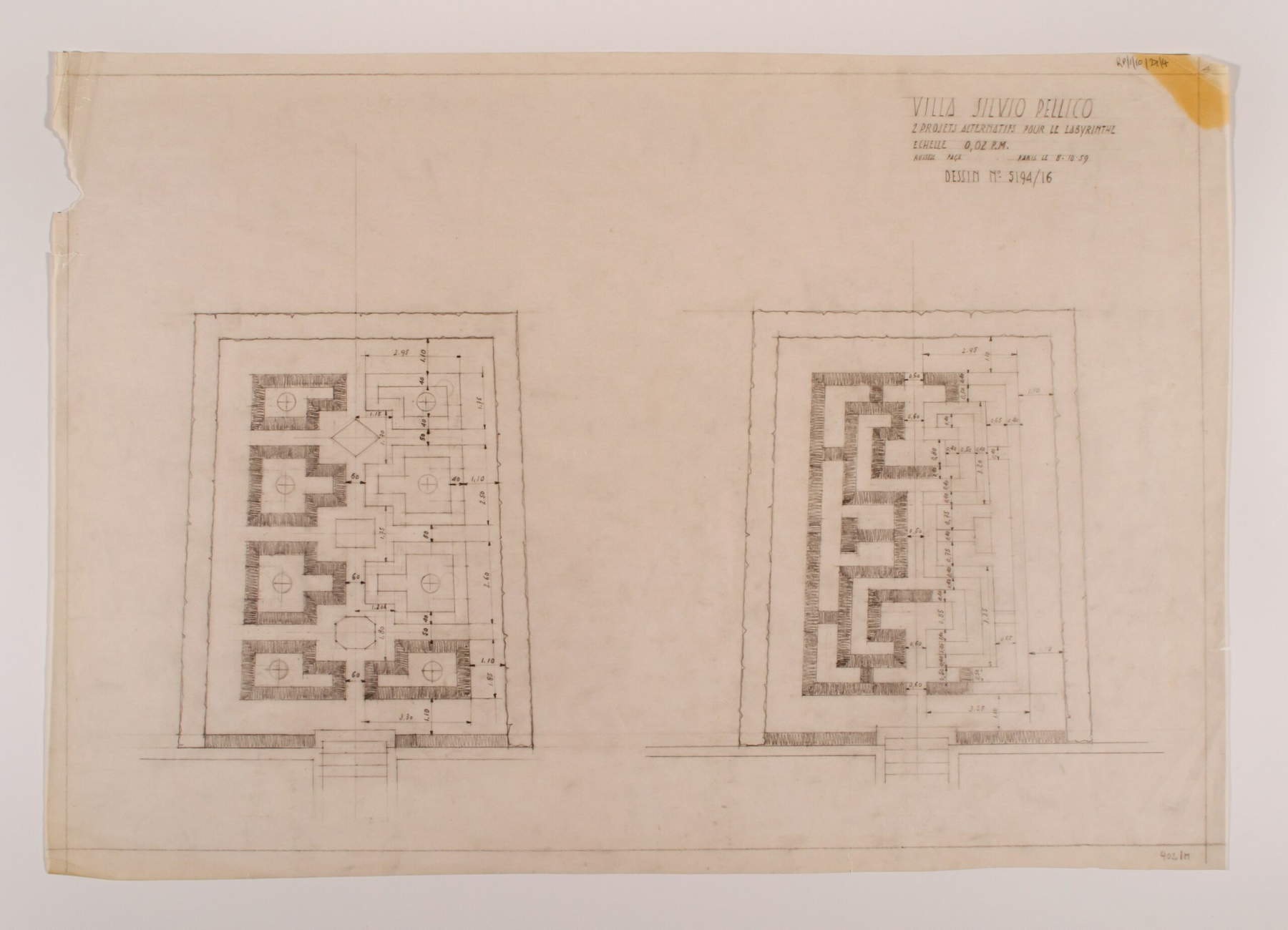

Thus Russell Page, through an enlightened vision outside the traditionally imposed box, created in Moncalieri, just outside Turin, the Barolo Vineyard Park, also known as "Villa Silvio Pellico,“ which stands out today as one of the most internationally renowned gardens. It is considered a masterful synthesis of the Italian tradition and the Anglo-Saxon school in the art of gardens, and its fame is due not only to its historic nobility, but also to its reserved aura that preserves an unspoiled grace over time. Between 1820 and 1850, the so-called ”Italianate Style" became popular in Britain, marking a revival of interest in the architecture of 16th-century Italian villas, with a neo-Renaissance style that influenced English taste, including that in ’garden art. This cultural movement also marked the rediscovery of the labyrinth as a distinctive element of Italian gardens, giving rise to a series of paths that today constitute the historic heritage of the United Kingdom. Famous examples of this trend, Ettore Selli recalls in his book Italian Labyrinths, are the Chevening House of 1820, Woburn Abbey of 1831, Shrubland Hall of 1848, and many, many others. This style was later taken up in the famous Capel Manor Maze of 1989, which embodied all the principles of this school of thought and contributed to the great revival of the Victorian age, making Britain the world’s cradle of mazes.

Just after World War II, Russell Page, who was called the “Mozart of gardens,” dedicated his mastery to the Moncalieri garden, where he created what he called his most successful work. A love so deep, perfect and infinite that he also described it with transport in his 1962 book The Education of a Gardener. The residence, initially owned by the Marquis Falletti di Barolo, saw many prominent personalities pass through, such as Silvio Pellico, author of Le mie prigioni (My Prisons) in 1832, and from whom the villa derives its name. Pellico was housed when the villa was inhabited by Julie Colbert, daughter of Louis XIV’s finance minister, who had married Carlo Tancredi Falletti di Barolo: it was she who hired Silvio Pellico as her personal secretary, and tradition has it that My Prisons was written there. When Marquise Julie passed away, the villa became an orphanage run by the Barolo Foundation, after which it was sold to Baron Milius (who named it “Villa Silvio Pellico”), had the gardens restored, and for some time lived there. Later, the villa returned to the Barolo Foundation, and then was again sold to private owners. It was in 1948 that a young heiress bought it, deciding to save it from decay, and to commission Russell Page to redo the garden.

In 2007 it was acquired by Raimonda Lanza di Trabia and her husband Emanuele Gamna, who are credited with preserving and telling the story of this historic home. As one walks down the winding avenue, the secrets hidden by the garden gradually reveal themselves, dancing. The view is immediately captured by the majesty of the great hanging foliage of a Fagus sylvatica pendula (hanging beech), with its pungent scent whose fruits are always scattered along the slope.

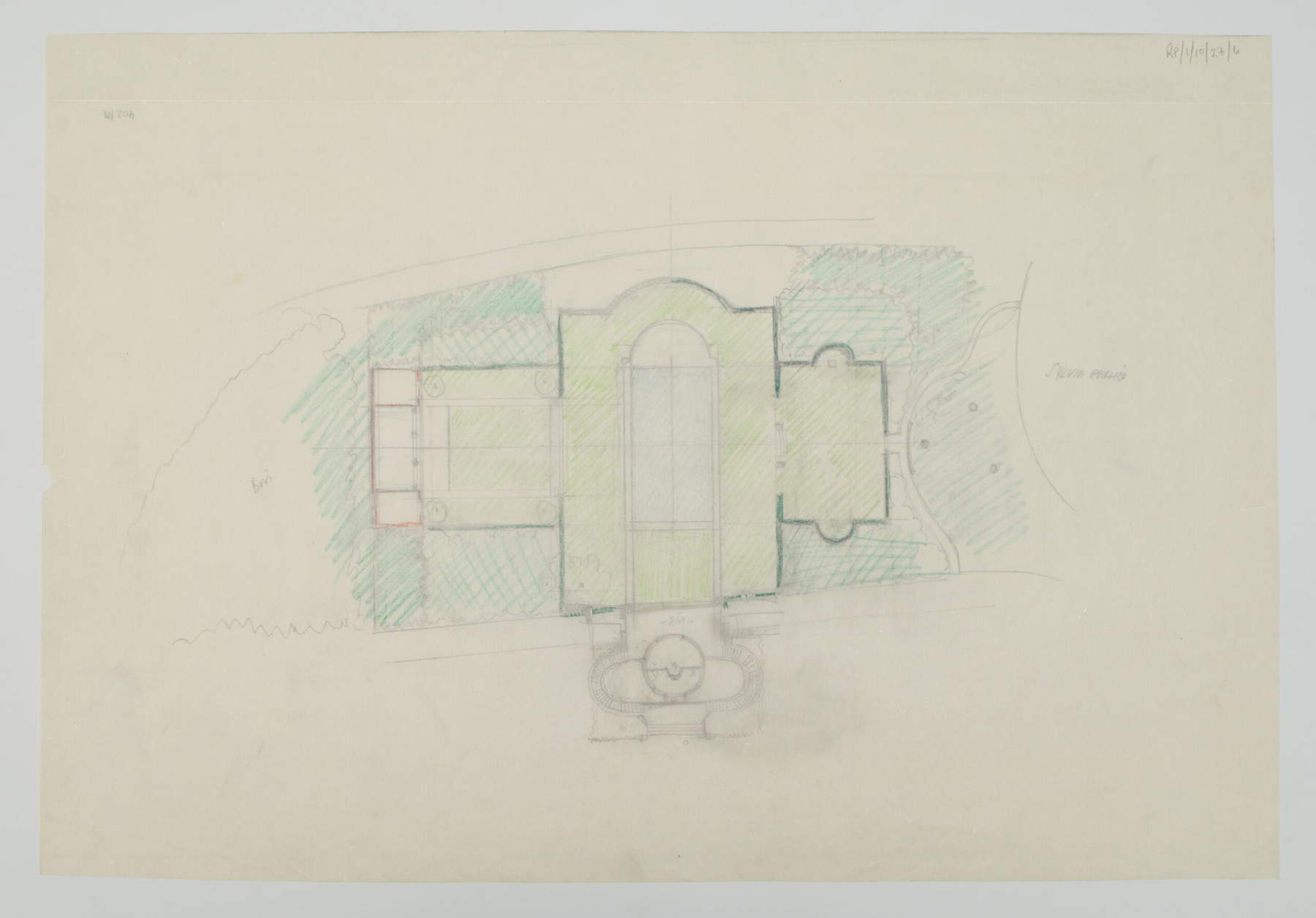

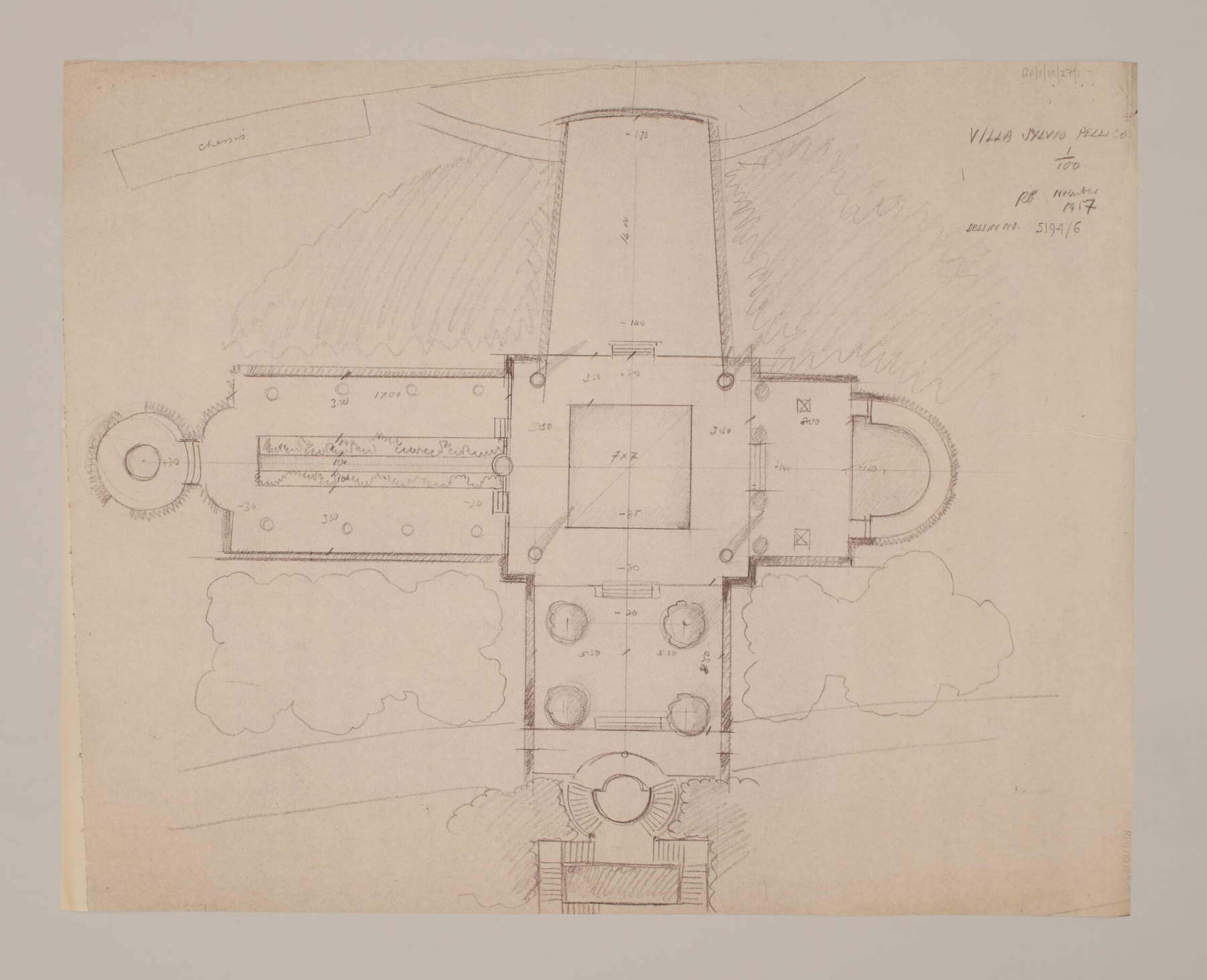

Continuing along the path, the boxwood “clouds” described by Ettore Selli thin out and among the centuries-old plane trees, probably donated by Napoleon, a triumphant panorama of two huge cedars, recently declared a national monument, and a little further on an emerald lawn is slowly revealed. Passing through the gate of the villa, one is confronted with a Renaissance-inspired garden with labyrinths, staircases, terraces, pools with spouts, nymphaeums, and topiary boxwood and yew hedges. The two ideal axes create an evocative perspective picture, in which the view is lost among hedges and pools of water, paving the way for the "Mock Labyrinth," a weave that, although not walkable, represents centuries of garden art.

Russell Page,

Russell Page,

Page’s envisioned solution for Villa Silvio Pellico, write Marina Schinz and Gabrielle van Zuylen in their 1991 book The Gardens of Russell Page, “was to build a new garden on a series of horizontal levels, framing each section with hornbeam hedges and connecting them with stone edged pools. With this general scheme in mind, Page had the land leveled, the steps built, and the pools excavated before he even figured out what he would do with the steep bank and how he would connect the garden to the upper level of the property. Eventually he designed a double staircase in three flights to connect the two. In front of the mansion he had a lawn cut in two by a brick driveway. Square borders of roses supported by camellias on either side of the path serve as a quiet introduction to the neoclassical formality of the garden below. Looking down from the level of the house, the view along the main axis is the first of two rectangular parterres, each edged with boxwood and outlined in diamond patterns. The interior spaces are filled with santolina, cut slightly higher than the boxwood. The second section contains a square reflecting pool, while the third is composed of boxwood and white gravel with an arabesque pattern. Paths of pink brick arranged in a herringbone pattern join these levels.” Schinz and Van Zuylen identified one of the most interesting features of the garden in the “cross-axis extensions.” Indeed, to the left of the square central pool, accessed by a ramp of five steps, is a slightly raised canal garden, while to the right is another lower and smaller one. “No other classical garden created by Page in Europe,” the two scholars wrote, “better illustrates his extraordinary ability to interpret the nature of a site than Villa Silvio Pellico. The project demonstrates his mastery in turning a problematic case, in this case the hillside location, into an advantage. The garden with its green trees and shrubs, stone spaces and workings, and changes in level and perspective provides an oasis of calm and peace despite its proximity to a bustling city.”

The labyrinth, sphinxes, and allegorical statuary are mute reminders of a whispered message between revelation and awe in which the precise lines of boxwood hedges create an evocative rectangular pool of water, while the intricate labyrinth opens onto the city below. On either side are two more water gardens, adorned with elegant neoclassical stone statues. The more formal area is thus surrounded by a relaxed and informal atmosphere typical of English parks, with leafy groves, boxwood paths, majestic palms, lush ferns, acanthus and towering cedars of Lebanon. In this corner of romance, a bench rests around the trunk of a leaning beech tree, while the branches of the oldest beech tree house a small cottage. Enveloped in the history and melancholy beauty of its surroundings, this entangled plant maze enchants the eyes and soul of visitors .

|

| Villa Silvio Pellico, the garden and the labyrinth: Russell Page's Italian masterpiece |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.