As of October 19, 2025, French radio stations are broadcasting Un mauvais rêve de SandroBotticelli (A Bad Dream of Botticelli https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceculture/podcasts/allons-y-voir/un-mauvais-reve-de-sandro-botticelli-6063000). The first five minutes of the broadcast set the tone, as they say in music. Medievalist Patrick Boucheron proclaims on air, “We have to deal with this culture of feminicide ... ” which would have originated exactly in 1483, and no earlier, in a cycle of four paintings by Botticelli telling the story of Nastagio degli Onesti. For Professor Boucheron, these Botticelli paintings openly promote “gynocide.” Just enough to astound connoisseurs of the Florentine painter who, after a lifetime of research, suddenly discover that their hero was none other than the sadistic inventor of pictorial femicide. Everyone is entitled to their own opinion, but quite different is the position of professors: their educational mission obliges them to righteousness and open-mindedness. A truly difficult synthesis. The privilege of fame does not abolish this duty: on the contrary, it doubles it. It is therefore legitimate to politely express our skepticism as specialists of the fifteenth century toward this nightmare that Sandro Botticelli does not deserve.

Already subjected to the unrestrained interpretation of Georges Didi-Huberman in Ouvrir Vénus (Paris 1999), an essay in phantasmagorical analysis, the fable in question depicts a well-known hero of Boccaccio’s Decameron, immersed despite himself in a terrifying hunting scene. Does the tempera on panel from the second episode of this fable, preserved in Madrid (Fig. 1), reflect Botticelli’s unbridled sadism? Before pronouncing, it would be better to know how to look at, question and understand a painting. Otherwise, as the irreplaceable Daniel Arasse used to say, “you can’t see anything in it.” Here is a demonstration of that.

Botticelli’s art stylizes Boccaccio as a horror movie in which Nastagio witnesses the agony of tragic love, which he experiences firsthand. Scorned by the beautiful Bianca Traversari, whom he loves in vain and who is causing his downfall, Nastagio wanders, consumed by grief, through a dark forest and stumbles, a supernatural vision, into an infernal hunt modeled on Dante Alighieri’s 13th canto ofInferno (109-129), in the circle of suicides, an absolutely crucial detail. Terrified, Nastagio sees a woman chased by a hunter and his dogs, thrown to the ground where her heart is ripped out, only to rise again, unharmed, and resume her desperate escape. The hunter and his prey are two damned spectres. Madly loved by the phantom hunter, the haughty woman belonged in life to a far nobler family, but after remorselessly driving her unworthy lover to suicide, she ends up atoning beyond death for the monstrous cruelty she had rejoiced in without feeling the slightest repentance. She is thus a “Beautiful Lady Without Pity.” She ripped out his heart on earth, out of class contempt, and he rips out hers in the afterlife, after piercing her with a sword, the instrument of his own suicide. In contrast, all ends well for Nastagio and Bianca: the ghostly example drives them to marriage.

The powerful initial motif of a difference in rank and fortune, fundamental in the Middle Ages, sets in motion the drama of contempt, then the tragedy of suicide, a mortal sin that in turn brings about supernatural compensation through the very weapon of suicide, as intended by Dante, who called this divine justice “contrapasso,” a kind of law of retribution. But in the work of the bourgeois Boccaccio, later than Dante, the socio-economic factor prevails. It is not sexual in the sense in which we understand it. Moreover, in the Middle Ages as in the Renaissance, the passionate love felt by Nastagio was often classified as a disease of the elite, in accordance with the Greco-Arabic medicine Latinized by Constantine the African (d. 1087) and Gerard of Cremona (d. 1187). It does not translate a romantic feeling, much less the great media emotion that is fashionable today. He who goes mad with love, does not cry on Facebook: he departs from the human consensus to die. Hence Nastagio’s sylvan isolation. What certainly recalls Eros in Boccaccio is this love death of the aristocrat, mesmerized by the female icon, a typical case of fatal melancholia with its visual delusions. It is not caused by the woman’s “sex” in the genital sense, but by hereos, the Latin equivalent of the Arabic term ilisci, this lovesickness that infects the imagination at the center of the brain and turns the hallucinated lover into a suicidal madman, ready to let himself starve to death. Boccaccio rightly points out that Nastagio “does not remember to eat or anything else.” Beginning with Rufus of Ephesus (150 B.C.), Rhazes (d. 925), Avicenna (d. 1037), Constantine the African (d. 1087), and Arnoldo da Villanova (d. 1311), physicians sought to understand and treat this self-destructive frenzy, which has been extensively studied by eminent specialists in France and Italy (see E. Ciavolella, La malattia d’amore dall’Antichità al Medioevo, Rome 1976; D. Jacquart and C. Thomasset, Sexualité et savoir médical au Moyen Âge, Paris 1985, pp. 115-120 and J.-Y. Tilliette, Les fous d’amour au Moyen Âge, de Tristan au Roland Furieux, “P0&SIE,” 159 / 1 (2017), pp. 134-42). All this is said for good measure, to provide a solid cultural antecedent to Boccaccio’s Nastagio, never offered by this strange rebroadcast of France Culture.

We give credit to Ms. Ana Debenedetti, director of the Bemberg Foundation, for attempting, during the first twenty minutes of the program, to contextualize and modulate, albeit timidly for our tastes, the denunciatory virulence of an inverifiable slogan: Botticelli was the first ever director of the patriarchal massacre of women. His “bad dream” was female subjugation, the “gynocide” taught in images during the Renaissance. The reasoning (if you want to call it that) makes no bones about it. Let us now subject it to a calm analysis.

First, how does the initial misunderstanding of this argument work, from which a series of factual errors and fallacious shortcuts flow? Suffice it to think about it: the painting in question was never the bad dream of Botticelli, who was simply the painter in charge of painting Boccaccio’s story, but rather the hallucination of a Nastagio destroyed by love melancholy. Let us keep in mind this absolutely crucial biographical distinction, which is too easily overlooked.

The only authentically autobiographical dream in which Botticelli was both actor and narrator is the one we found in Angelo Poliziano’s Pleasant Sayings and later studied in our essay in French Le Songe de Botticelli (Hazan 2022, pp. 17-19 / https://lunettesrouges1.wordpress.com/2023/02/03/mars-plutot-que-venus-botticelli/). In short, what does it tell us? Botticelli’s deep revulsion for marriage as he flees from the woman he is forced to marry against his will in a dream. This is exactly an inverted Hypnerotomachia. Indeed, handsome young men were always the marked preference of Lorenzo the Magnificent’s painter, and Lorenzo himself alluded to them with burlesque double entendres in his poem I beoni, a kind of Bacchic banquet completed two years after the Nastagio cycle (see Le Songe de Botticelli, pp. 124-127). The dates coincide. This element is particularly uncomfortable for Didi-Huberman’s thesis and its corollary of a painter forcing women to marry under the visual threat of dismemberment depicted in his Nastagio. It almost seems as if Botticelli himself would have been torn apart rather than marry a lady! Despite everything, will it continue to be argued that Botticelli is Boccaccio’s accomplice and thus co-responsible for the crime? But the layers of meaning in Boccaccio’s narrative refute the arbitrary postulate of libidinal violence triggered by males in heat. Is everyone guilty? Not really. Boccaccio is a fine author, his narrative is complex, undergirded by a theological moral, and Botticelli has depicted the horror and, above all, the courage of Nastagio who rushes to the aid of the spectre of the unfortunate victim. As Boccaccio relates, he desperately tries to prevent the murder, armed with a long branch in the guise of a stick against the molossi (Fig. 2). He still believes he is saving a real woman. There cannot be the slightest ambiguity.

Nastagio immediately accuses the hunter, whom he bravely confronts, of behaving as a vulgar murderer and not as a noble knight bound to respect a woman, a human being to be defended at all costs: “I don’t know who you are that you know me thus, but so much I tell you, that great cowardice it is of an armed knight to want to kill an unclothed femine and to have the dogs at her ribs as if she were a salvation fair; I for one will defend her as much as I can” (Boccaccio, Decameron, V 8, lines 50-52 ed. V. Branca, Turin 1992). Only after realizing that he is dreaming, and faced with the reaffirmed and unyielding divine will of the contrapasso, do we see Nastagio reluctantly resign himself to witnessing the mock execution, shivering with terror (Fig. 3). It is worth noting this stark physical and moral contrast, plastically translated by Botticelli. Moreover, the fantastic revelation confirms that the carnage, never really committed, is only an imaginary apparition. How is this possible? Nastagio is probably contemplating what Robert Klein, in La Forme et l’Intelligible (Paris 1970, pp. 89-124), called a “Ficinian hell,” a hallucinatory space of imaginary atonement in which the damned souls, according to the philosopher Marsilio Ficino, a true Laurentian Plato, repeat their sins and reproduce their vices ad infinitum, as we explained in 2017 in Voir l’Enfer (https://shs.hal.science/halshs-03844334/document).

But let us move on. The fact that the dismembered heroine in Boccaccio’s tale is not a Venus or a nymph at all, but an autonomous literary character, did not upset Didi-Huberman, nor does it upset his disciples, who are hardened to the master’s error, any more. What do they care, after all, that Botticelli’s Aphrodite is not a martyr, but the goddess of sumptuous flesh in the Birth of Venus that we admire in the Uffizi, as distinguished art historians have established? It is another evidence denied. Why is that? Because “not only beautiful things happen to Venus” (said Didi-Huberman). In such words, they try to convince us that the Renaissance, again he, invented the eternal ordeal of women, the same ordeal that is tragically displayed on the front page of our harrowing contemporary chronicles.

Let us begin with a basic observation: in fact, Boccaccio and Botticelli recycle the very old misogynistic tradition of medieval fabliaux, such as the very violent Dame écouillée of 1225 (ed. C. Debru, Paris 2009), a virago whose buttocks are slashed. So much for the invention of the 15th-century Florentine ! The transmission never mentions it and completely ignores iconographic investigation, as if, during the Renaissance, ancient and medieval literary texts had not wisely informed the images, designed to make us ponder and investigate what they conceal beneath the surface.

We must also lament this blatant methodological breakdown: the factual and temporal gap between pictorial fiction and contemporary murder is simply denied, and this denial is unfortunately hidden beneath the accusation. What good is historical distance, guarantor of accurate judgment? No, the 15th century would be worth as much as the 21st century, and the Renaissance painter would think like the murderer in our courts. At this degree zero of art history, and of history tout court, I regret to note that a brazen hermeneutic denial prevails among Botticelli’s detractors. As a result, his painting is arbitrarily divorced from its historical-aesthetic context. Vienne is crushed on bland topicality. Art now has only one level of meaning and one dimension: crime. To paint a literary fiction in the 15th century would be, in concrete terms, to instigate a pack of sadistic men in 2025 to punish a woman for sexual denial. Even, contemporary criminality would imitate Florentine painting. The fifteenth century thus finds itself relentlessly trapped in modern fantasmatology. Poor Warburg, poor Panofsky, poor Baxandall!

We are not falsifying any of these assertions. They are verifiable. They mix without discrimination news reports and ancient paintings to amplify a morbid emotion. It is a visual sophistry, an “emotionalization” of art that privileges romanticized emotionalism at the expense of iconographic elucidation. A counterexample should suffice.

What would we think of an art history if it claimed that the brilliant Domenico Ghirlandaio painted his bloody Massacre of the Innocents (Fig. 4) in the Tornabuoni Chapel in 1490, depicting mutilated, amputated, and decapitated infants to glorify mass infanticide, such as that perpetrated before our eyes in Gaza or elsewhere? We would think that this discipline has lost its mind, that it is irrational in the sense that an uncontrolled pathos brutally undermines its logic. It would seem that it teaches nothing, that it mistakes its audience for a people of mindless emotionalists, too stupid to merit explanation.

Consequently, no one ever tells us about aesthetics or iconology, but about evidence, albeit highly manipulated, certainly. A painter’s work is criminalized, but it is not just any painter: the beacon of Florentine cultured painting and Renaissance humanism, the black beast of the anti-humanists, is obscured. This kind of defamation, whether intentional or not, falls into the ranks of other, cruder and more aggressive forms of vandalism against art (which include soup-throwing and other similar acts), which nevertheless exploit the same principle of negative notoriety: attacking the very essence of art, stifling all forms of admiration with vengeance.

The media effectiveness of such cultural policing rests on its blindness. Dragged before the vice squad is the posthumous perpetrator of a pictorial crime he never committed, first of all because it was not his dream, and then because it belongs to the realm of the unreal, to the very essence of art. A fiction? Who cares! Botticelli, this criminal of the brush, whose artistic credentials are now worthless, has no right to a defense in such a court of law. Is this why the admirable scholarly work conducted by Alessandro Cecchi, Cristina Acidini and other specialists is deliberately ignored, along with Vittore Branca’s masterful studies(Boccaccio visualizzato, Turin 1999) and Monica Centanni’s(La Calunnia di Botticelli, Rome 2023) on the iconography of the Decameron, which is precisely the subject of this program? Similarly, the certainly uncomfortable teachings for the prosecution, of scholars like Gombrich and Panofsky are dismissed from a one-sided perspective that resembles a copy-paste of the theses of Didi-Huberman, a self-proclaimed opponent of Panofskian intellectual humanism in France (see his Devant l’image, Paris 1990, pp. 135-145).

To be exhaustive and not overlook anything, let us consider the additional clue offered by a guest, Ivan Jablonka, a modernist and novelist specializing in feminicide, who also firmly believes that “Botticelli participates in a gynocide culture.” What does “participates” mean? A mystery. The author of Laetitia, a novel about a horrific dismemberment that really happened-which he says “is not very different from Botticelli’s” (sic)-provides overwhelming evidence of the misappropriation of sources. Here it is : the Renaissance prints anatomy treatises full of flayed women, dissected wombs and female viscera. The “gynocide” painter obviously belongs to this sad lineage of mutilators. Yet, if we deign to remember, the great Vesalius also dissected many little boys, while 16th-century anatomists, accustomed to dissecting male organs, diligently plunged their blades into penises, testicles and virile bladders, as evidenced by a meticulous drawing by Leonardo da Vinci preserved at Windsor Castle (see R. L. 19098v). Incidentally, isn’t this Leonardo, this careful drawer of female dissections, also a vile “gynocide”? Ah! How to cut it short? It really has to be said. We see the price to be paid for confusing sexual delinquency, painting and scientific dissection in the name of an artistic moralism that Jacques Guillerme had already denounced in his Atelier du Temps (Paris 1964).

Speaking of delinquency, an investigation in the criminal archives would have been desirable to see if Botticelli ever mistreated any damsels. Is not life like art, and art like life, at least according to the artist’s radio accusers? Isn’t the program entitled Allons-y voir (“Let’s go and see”)? In fact, we had gone to see in 2022, in Le Songe de Botticelli, the factual accusations made against the painter, which we meticulously studied in Florence in the archives of the Ufficiali di Notte, the Florentine vice squad of the time : they reveal, on the contrary, his “sodomite” tendencies, that is, his exclusive love for ephebes. Such a precedent seems a bit weak for a self-styled obsessive of female flesh, who moreover certain critics, it is true, ill-informed imagine to have been the unlikely lover of Simonetta Vespucci.

We confess one final concern, which we feel is legitimate in light of recent events in the art and activist movements. Doesn’t the feminist cause, as important as education and culture, deserve better? By symbolically destroying the Florentine heritage, who can seriously believe that they are promoting the dignity of women worldwide? Who honestly thinks they are making a constructive contribution to 21st century feminism? Such excesses could backfire on the good intentions behind them. Reactionaries and male chauvinists of all kinds are just waiting for this opportunity. The same oversimplifications could also otherwise harm Botticelli and his paintings, still spared from vandals of all kinds, greedy for flimsy justifications.

Let us cheerfully steer clear of these dangers and instead commit ourselves to defending a lucid art history for an informed public. Since we are talking about sex, let us consider ancient sexuality, a category challenged by Michel Foucault, the luminary of the Collège de France, as an object independent of our modernity, untethered from our norms and sex education. Hence the improbability of any cause-and-effect relationship between the 15th and 21st centuries. Clearly, gender roles were so porous in the 15th century, especially in Florence, that a purely criminalistic interpretation of Venus images is highly misleading. Therefore, Florentine chests depicting Venus or Helen of Troy are not necessarily, as the program negatively states, “sex education lessons that inculcate the total submission of women.” Were Florentine women really sex slaves to their husbands? This does not seem to be the opinion of our colleague Rebekah Compton(Venus and the Arts of Love in Renaissance Florence, Cambridge 2021, pp. 61-73) when she insists, rightly in our view, on the exaltation of female flesh and fertility, socially positive values in the Medici era and triumphantly embodied by Botticelli’s Venus. If further proof is needed, one need only visit the Louvre to admire a birthing table (Fig. 5), where a glorious haloed Venus beams down on kneeling knights, from Paris to Lancelot, completely submissive to their goddess. So many chivalrous lovers gathered in the courtly dream of a garden filled with the presence of Eros (see the two red angels, endowed with passion-like claws, on either side of the almond), are not there to perform a “knee-jerk,” but to surrender. They capitulate by mutual agreement at the feet of their sovereign. Will this also be a sex education manual? But for the use of men kneeling in peaceful adoration of the queen of women!

And as far as it pertains to so-called macho sadism, which they say is typical of the Renaissance, if it really exists, perhaps that it never meets its opposite, which is the overthrow of woman over man? This question is worth asking. And its answer is known only to the “workers of the spirit,” as Alfred Weber, brother of the great Max, liked to call them, i.e., the intellectuals who still daily frequent museums and libraries for their obscure and silent research, far from an increasingly ignorant and inept media sphere.

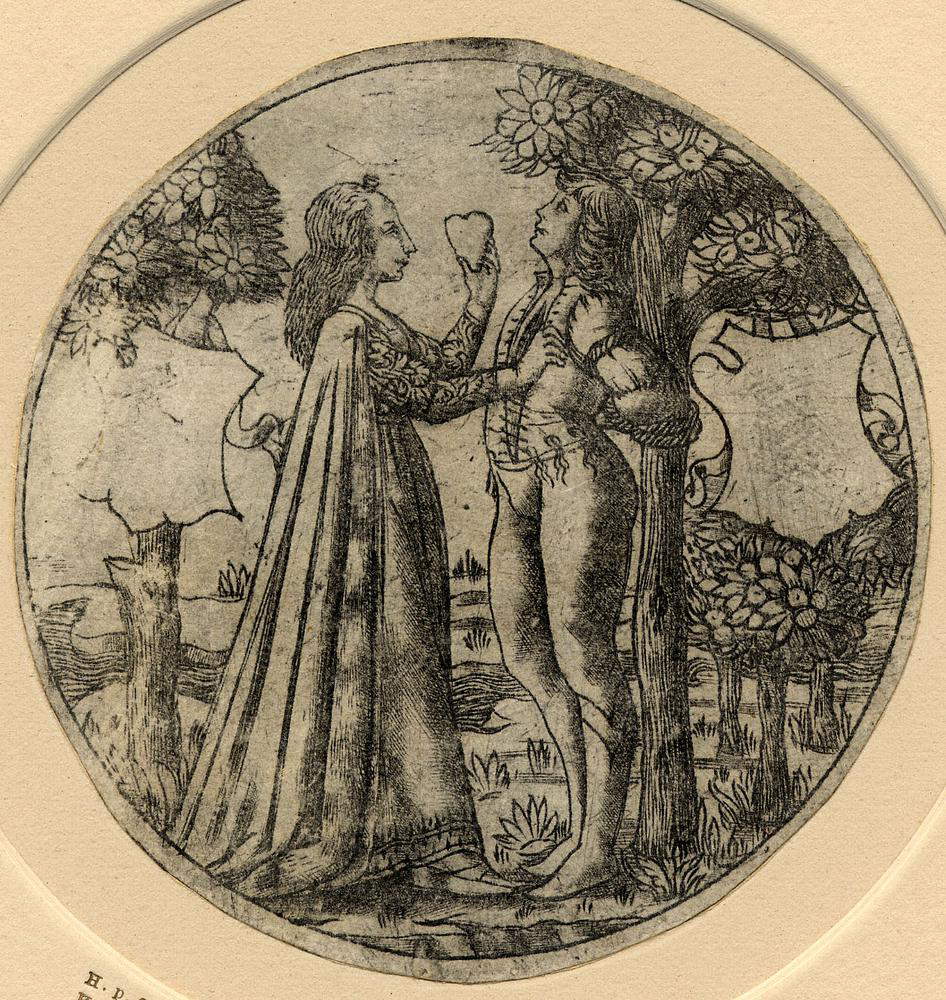

So let us now consider this Florentine engraving entitled Cruelty of Love. We have chosen it among the famous Otto Prints (Fig. 6) from the workshop of Baccio Baldini, Botticelli’s contemporary. It really deserves to be discussed. What can we see in it? A noble lady is tearing out the heart of a lovesick page, captured and tied to the tree against which she is undergoing her erotic cardiotomy. Are we not in a forest, like Nastagio degli Onesti? Surprisingly, the victim this time is a handsome young man. This is how the cruel medieval law of mutual love works, which we wish to emphasize and which no lover could break without paying the price. The lady ripped deeply into his chest to grasp the male heart, which she wields with pride. Then would a woman dismembering a man be any less horrible? Here is a good question.

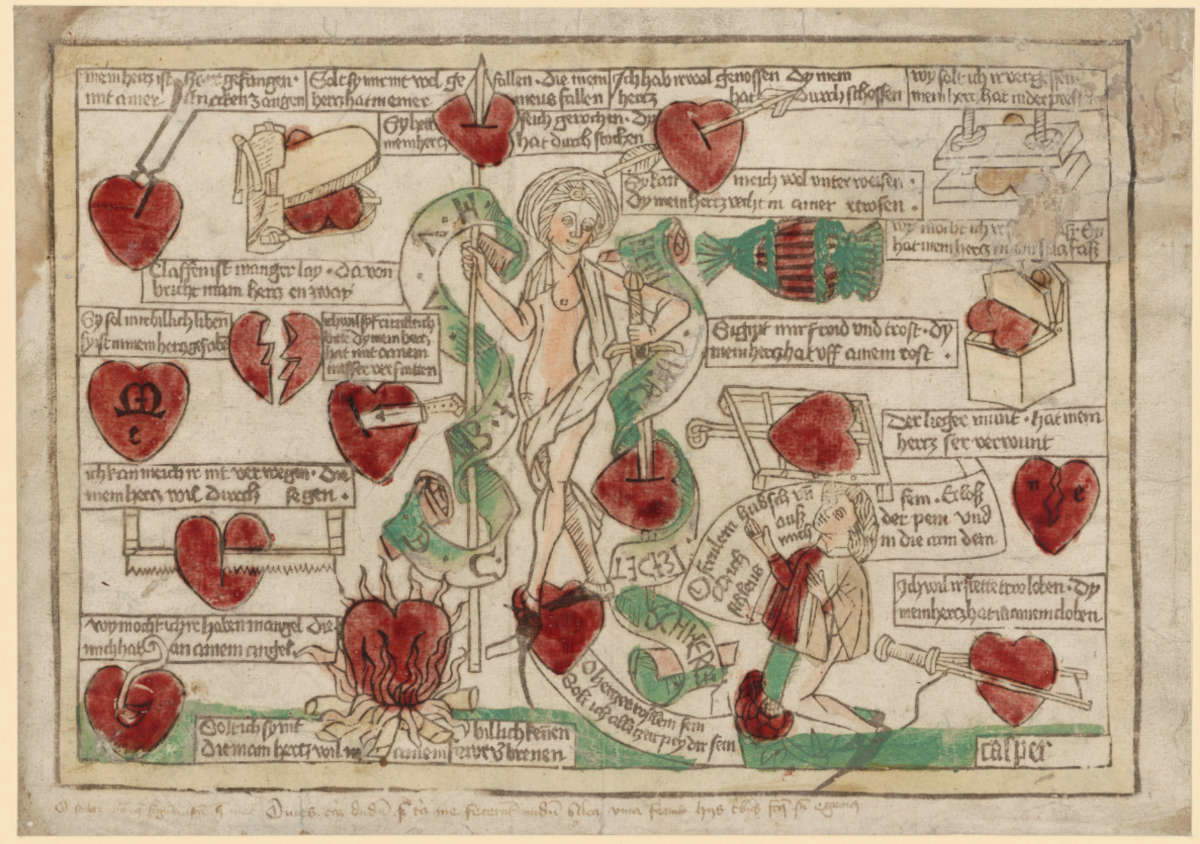

Finally, consider the ruthless Frau Venus und der Verliebte, or Lady Venus and her lover (Fig. 7), in German Casper’s engraving around 1485, right around the time of Botticelli’s Nastagio. Observe closely this murderous Venus, armed to the teeth, as she extracts, stabs, crushes, slashes, saws and burns the huge and multiplied red heart of the poor, overwrought young man, ready to face for his beloved the harshest trials of an undeniably medieval BDSM prison. For the edification of the audience, we gladly translate from Old German excerpts from the monologue that the condemned man devoutly addresses in cartouches, as in an amusing comic strip, to each instrument of his martyrdom:

"She took care to pierce my heart (the spear of Venus)....

I loved so much the one who pierced my heart (the arrow of Venus)....

I have to thank her for breaking my heart with one stroke of her blade (the dagger of Venus)....

I cannot resist her who sawed my heart in two (the Venus saw)."

With a dash of humor and paraphrasing Didi-Huberman, who will surely forgive us, we conclude by observing with a smile that “not only good things happen to the lover of Venus.” Eh, no! And we hope that so many contradictions and calmly explained counterexamples will restore a clear truth: history is a meticulous hermeneutic devoid of dogma, whose judgments must be calibrated and recalibrated with infinite precision. Its vocation is neither to condemn nor to argue, but to incite us to reflection and, above all, to make us understand facts, documents and images with perfect freedom of spirit. Somewhat like painting itself, which, according to Charles Baudelaire in his 1846 Salon, always remains “an art of deep reasoning.”

The author of this article: Stéphane Toussaint

Stéphane Toussaint (Saint-Germain-en-Laye, 1960) è direttore delle ricerche presso il CNRS - Università La Sorbona, Centre André-Chastel, Parigi. Laureato alla École Normale Supérieure di Parigi Rue d'Ulm, ha studiato filosofia e letteratura rinascimentale presso le Università della Sorbona e di Parigi-Nanterre. Entrato al CNRS nel 1992, ha poi conseguito nel 2002 l’Habilitation à diriger les recherches all’EHESS, con un lavoro sul Neoplatonismo e il Rinascimento, incentrato su Marsilio Ficino e il suo ambiente intellettuale. Il suo percorso accademico e scientifico è stato coronato nel 2009 dal prestigioso Prix Monseigneur Marcel dell’Académie Française, e nel 2011 ha ottenuto il grado di Directeur de recherche (DR1).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.