The urge to know our origins and to cherish the memory of the past has accompanied man since his earliest days. From the earliest burials enriched by objects belonging to ancestors to the recovery of vestiges and monuments, every civilization has sought a link to its own history. AncientEgypt, with its millennia-old culture represents one of the most powerful expressions of this link. The same impulse animates today’s Roman exhibition Treasures of the Pharaohs dedicated to the rulers of Egypt and set up inside the Scuderie del Quirinale, with more than one hundred artifacts from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo collected in a project curated by Egyptologist Tarek El Awady, former director of the Egyptian capital’s museum. Some questions arise, however: why dedicate an exhibition to Ancient Egypt again? How does the Rome exhibition differ from the many others that display blindfolded mummies and canopic jars?

In fact, one only has to step through the entrance of the Scuderie to immediately understand that the Rome exhibition is unlike any other. Treasures of the Pharaohs leads the visitor to question the origins of the relationship with Mnemosyne, mother of the Greek muses and personification of Memory. At the heart of the exhibition, composed of works from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and the Luxor Museum, there are no artifacts intended to trace a defined historical chronology. Rather, there are treasures that speak of splendor and eternity; there are gilded treasures that capture the light, the gaze and that restore, by their magnificence, the impression of being inside Tutankhamun’s burial chambers. Thus, from the works emerges the refinement that made Egypt the epitome of harmony and beauty. It is an elegance that blends with the dual nature of the pharaohs: the spiritual and the earthly. Spiritual because their power was nourished by a deep connection with the divine; human, on the other hand, because the rulers knew how to preserve the traces of the past and cherish their legacy as a gift for future generations. As early as the New Kingdom (1550 - 1069 BCE), the first forms of archaeological consciousness adopted by the pharaohs can be traced. Thutmosi IV, eighth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty, is one example. According to one tale, also cited by archaeologist Zahi Hawass, when he was still a prince Thutmosi fell asleep in the shadow of the Great Sphinx (then half-buried by the desert) and dreamed that the deity would grant him the throne of Egypt if he would release the monument. Once he became pharaoh, the man recovered the colossal-sized statue, restoring it to its original grandeur. A gesture that, according to the archaeologist, can therefore be read as one of the first actions to protect historical heritage.

About a century later, Prince Khaemuaset, son of Ramesses II, continued toward the same mission, devoting himself to the restoration of temples and burials in the necropolis of Memphis. His recoveries include the pyramid of Unas at Saqqara, where he had some blocks replaced and engraved an inscription documenting his commitment to preserving the memory of the past. It must wait many centuries, however, for interest in ancient Egypt to develop into a true scientific approach. Until the eighteenth century, research was dominated by antiquarian collecting more inclined to treasure hunting than to the study of historical contexts. The turning point then came with the Napoleonic expedition of 1798. We are talking about a military enterprise that soon turned into a giant laboratory of knowledge. The scholars in Napoleon’s retinue documented local flora, fauna, monuments and customs, resulting in the monumental Description de l’Égypte (1809-1829), a work that definitely opened Europe’s eyes to the pharaonic civilization.

Millennia later, the same impulse that first drove ruler Thutmosi IV still drives us to search the traces of ancient Egypt for something that speaks of us. What? The will to understand, to cherish what time tries to jealously keep for itself. The exhibition Treasures of the Pharaohs therefore stems from the same desire for knowledge and wonder. The pharaohs, earthly embodiments of the divine, sought in eternity proof of their greatness. Indeed, gold, an incorruptible metal sacred to the sun, enveloped their bodies as a promise of immortality. From all this the exhibition comes to life.

The exhibition is divided into tenthematic rooms. In the deliberately dark environment conceived by curator Tarek El Awady, objects emerge illuminated by the glow of gold, just as, presumably, the gods would have wished too. Opening the exhibition and dominating the scene is the colossal lid of the sarcophagus of Queen Ahhotep II (c. 1560-1530 BCE), the protagonist of one of the most fascinating finds in Egyptian archaeology. The cover, made of wood and gilded stucco, comes from the queen’s own treasure, discovered in 1859 by workers at Dra Abu el-Naga (on the west bank of the Nile), near Luxor. In fact, there are no official documents that accurately describe the location of her tomb, the original structure, or a complete inventory of the artifacts. All that is known is that Auguste Mariette, then director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, managed to recover the treasure from the hands of the mayor of Luxor. The latter, in an attempt to appropriate part of the trousseau, destroyed the queen’s mummy by unrolling its bandages. The lid of the magnificent “rishi” sarcophagus bears an inscription with the name and titles of the sovereign, Daughter of the King, Sister of the King and Great Royal Bride, without actually mentioning that of Mother of Pharaoh.

In any case, among the sands and mines of the Eastern Desert, the pharaohs knew how to extract gold, the element that more than any other embodies eternity. As early as around 3200 B.C.E., between the Neolithic and Predynastic periods, the Egyptians developed advanced techniques for prospecting and processing the metal. We also know that the oldest known mining map, the Mines Papyrus preserved at the Egyptian Museum in Turin, documents their knowledge of the land and its resources. Gold, abundant in the hills bordering the Red Sea and in the south of the country, soon became a measure of value and a symbol of power. An incorruptible metal, immune to decay and time, it was associated with the very body of the gods. Divine statues had to be forged from pure gold, just as gold was used in mummification rituals to protect the remains of rulers and nobles. Funerary masks, sarcophagi and amulets restored sunlight, an earthly reflection of rebirth and promise of eternity.

The goldsmiths of ancient Egypt, masters in the art of detail and symbolism, thus knew how to transform metal into language. The jewelry, collars and bracelets, thus told of hierarchies, divine ties and aspirations to immortality. More than forty gold artifacts in the exhibition restore this same immortality. Among the works on display in the first room is the large collar of Psusennes I. Made of gold, lapis lazuli, carnelian and feldspar, it dates from the time of the XXI Dynasty (Third Intermediate Period) and is composed of seven strands interwoven from more than six thousand gold discs. It is considered one of the most impressive pieces of jewelry of antiquity that has come down to us, a symbol of the technical perfection and refined taste of the Egyptian court. Alongside the collar, other royal jewels complement its magnificence: the bracelet of King Ahmose I, the five gold bracelets of Sekhemkhet, and the delicate bracelet of a princess.

What awaited the Egyptians after death? The answer is revealed in rooms 2 through 5, rooms enveloped in a solemn and rarefied atmosphere. Here each artifact occupies its own space with royalty. As soon as one enters the second room, one’s gaze is caught by a monumental presence: the outer anthropoid sarcophagus of Tuya, made of wood covered completely with gilded stucco, with fine inlays of blue glass, obsidian and colored stones, and belonging to the 18th Dynasty (the time of the reign of Amenhotep III). In fact, the room dominated by the central sarcophagus is flanked by the grave goods that belonged to Tuya and a number of objects documenting his close association with the royal family.

The discovery of Tuya and Yuya’s burial in the Valley of the Kings on Feb. 5, 1905, marked a turning point in the history of archaeology. Egyptologist James Quibell, under the patronage of Theodore Davis, unearthed an almost intact tomb, an unprecedented event for a couple outside the royal family. The couple were in fact honored with a tomb in the necropolis of the pharaohs for their connection to Queen Tiye, daughter of the couple and Great Royal Bride of Amenhotep III, the first ruler to proclaim himself god incarnate, calling himself “Aton dazzling” in the 11th year of his reign. Yuya was a high dignitary, “Father of the god” and “Commander of the royal cavalry”; Tuya, on the other hand, was a priestess and “Singer of Hathor” (the same goddess depicted in the gold and lapis lazuli pendant displayed in one of the later rooms), guarding roles of great prestige.

In this regard, we know that Egypt’s conception of the afterlife reflected a cyclical view of existence. As the sun rises and sets, as the Nile recedes and returns, human life was also a continuous passage marked by birth, death, and rebirth. To access eternity, however, burial was not enough: it was necessary to preserve the mummy, donate offerings to the deceased, and keep his or her name alive through inscriptions and images. The artifacts in the rooms thus include ushabti, small figurines that prodigiously replaced the deceased in the workings of the Fields of Iaru. One of these, depicting Yuya himself, comes from his tomb and documents the ancient belief that life in the afterlife was a symbolic continuation of life on earth. Also in the room is Yuya’s canopic casket with a lid carved with a stern, hieratic face.

The next section introduces us to the everyday objects of the deceased. A stone headrest and an elegant wooden bed by Yuya and Tuya. The headrest also had a sacred function: its shape recalled the horizon from which the sun rises, a promise of awakening and eternal life. The path then leads to the hall of treasures belonging to Pharaoh Psusennes I: the gold and silver covering of his mummy and the headrests, also made of gold. There are also gold bracelets, breastplates and anklets from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo of various rulers. Alongside, the Papyrus of Djedkhonsuiusankh, Amun’s chanter and a document from the Third Intermediate Period, shows us the intensity of faith and the connection to the afterlife. Indeed, the Egyptians feared that the true death came only when a man’s name was forgotten. Therefore, to face the unknown, the deceased carried amulets and sacred texts: from the Pyramid Texts and Sarcophagi Texts to the Book of the Dead, a collection of formulas that guided the soul on its journey to immortality.

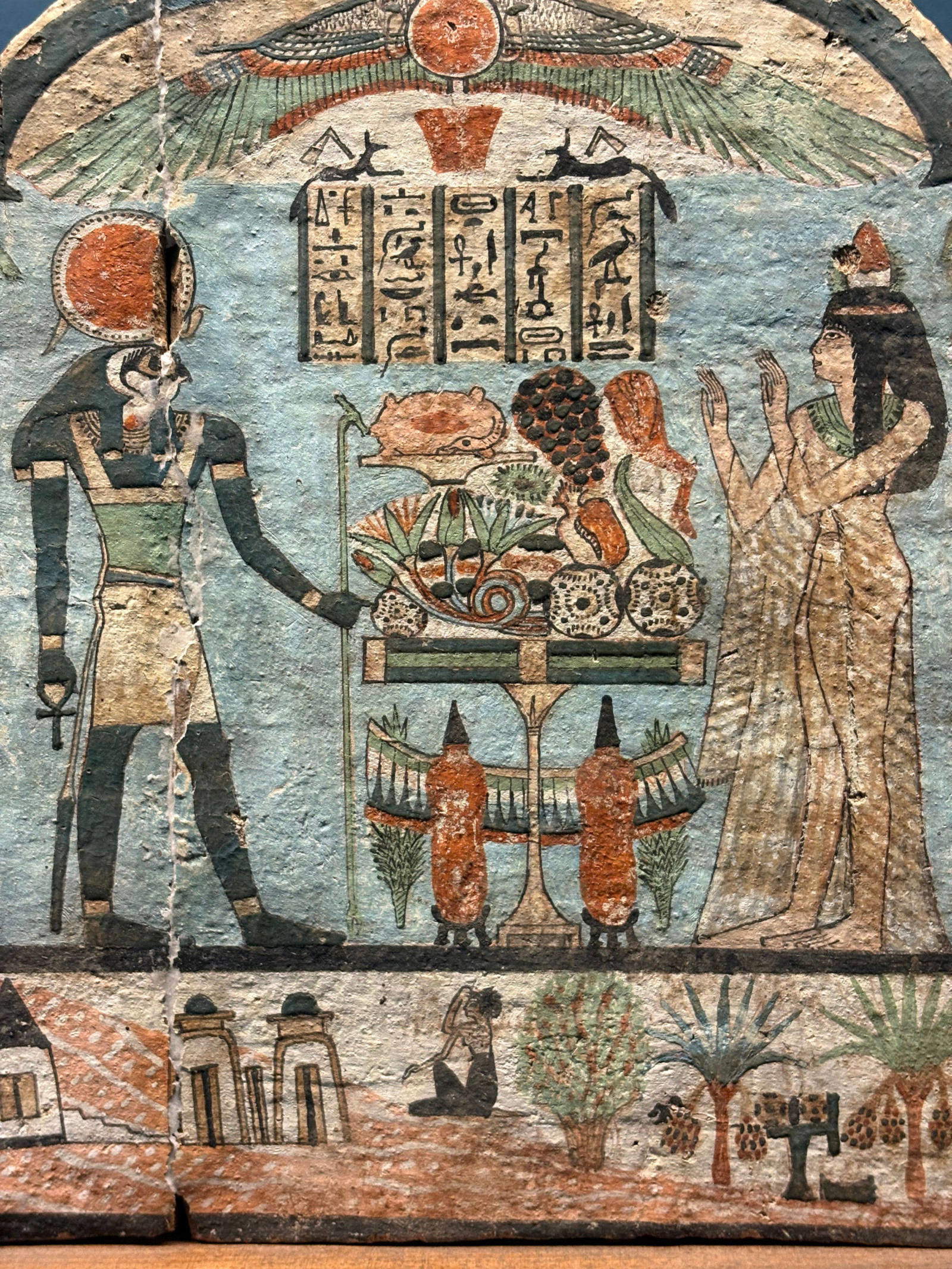

The soul was judged in the Hall of Osiris, where the heart was weighed against the feather of Maat, a symbol of justice and truth. Only those found to be pure could reach the Fields of Iaru. The hall’s path ends before the lid of the inner sarcophagus of Ankhefenmut, dating back to the 21st Dynasty, and five funerary stelae from Abydos, a sacred site dedicated to Osiris. On each stele, the deceased is portrayed in front of the offering table, surrounded by family members, in a gesture of deep devotion. A key element of each Egyptian stele was also the inscription that stated the name of the deceased and contained the ritual formula for the presentation of offerings, handed down since antiquity. All the inscriptions began with the words “An offering that the king grants, an offering presented by Osiris, lord of Abydos...,” indicating how, for the Egyptians, pronouncing the name of the deceased was tantamount to granting his immortality.

Rooms 6 and 7, on the other hand, introduce a new chapter in the itinerary. Here the atmosphere changes. The light becomes barely brighter and the material more solid, more concrete. The gold that previously evoked the immortality of the spirit and the divine grandeur of the pharaohs gives way to stone, a symbol of earthly reality, everydayness, andhuman order. There are no longer the splendors of absolute power, but rather carved faces, seated scribes, families of rulers. Instead, we are shown the world of the men who built and sustained the Egypt of rulers. Who supported the pharaoh. At the origins of Egyptian civilization, around 3200 BCE, pharaohs were called shemsu Hor, “followers of Horus.” Kingship was perceived as a divine gift, and the whole society found harmony in it.

The pharaoh was the balance point between heaven and earth; he was the guarantor of order and justice. Over the centuries, however, the Egyptian hierarchy opened up and personal merit became the gateway to prestige and power. Egypt was not a static world, and architects, scribes, and officials such as Imhotep or Senenmut were proof of this. They were indeed men of the people who, through talent, reached the highest positions in the kingdom. In this part of the tour, the eye encounters the reserve head of Prince Seneferuseneb, one of the most fascinating finds of the Fourth Dynasty. But what is a reserve head? According to some scholars, the limestone reserve heads served as a symbolic guide for the soul, pointing the way to burial; others speculate that the visible fractures in the head were intentionally inflicted, representing the earthly death of the deceased and the liberation of his spirit in the afterlife, a necessary moment in the process of rebirth.

The setting of the seventh room then adds a scenic touch. In front of the visitor is a statue of Mayor Sennefer, shown with his wife Senetnay and daughter Mutnefret. Behind them, a panel decorated with floral motifs creates an optical effect that isolates and enhances the family group. Finally, a small object concentrates in itself the power of all Egypt: the famous Udjat Eye, molded in wax, an emblem of healing and rebirth. According to legend, it was in fact the lost and then found eye of the god Horus, a symbol of the victory of order over chaos. In ancient Egypt it was laid between the bandages of mummies to protect them, but also worn by the living as an amulet against evil.

Continuing along the path, we come to the section devoted to daily life. The atmosphere changes again. Here the tones turn to red, the color of fertile land and labor, a direct reminder of Egypt’s vital rhythm. The civilization’s crafts and buildings were a reminder of its geography and deep connection to the Nile, an artery that fed the country, made the countryside lush and fostered trade and commerce. We understand from the section that the day began at dawn. Farmers drove their livestock into the fields, fishermen lowered their nets, artisans fashioned wood, gold and stone, while scribes, in temples and schools, transcribed knowledge of the stars, medicine and calculus. Women, pillars of society, contributed in the fields, kilns, breweries and shrines, guardians of an ancient balance. When the sun went down, life retreated to homes: simple dwellings with inner courtyards for the people, sumptuous palaces for the elite, where the walls told painted stories and banquets came alive with music, scents and song.

A leap in time then leads back to the City of Gold, the incredible archaeological discovery announced in 2021 by Zahi Hawass. In an effort to find Tutankhamun’s funerary temple, archaeologists unearthed a perfectly preserved city dating back to the reign of Amenhotep III, dubbed “the domain of the dazzling Aton.” Located on the west bank of the Nile near Luxor, the city proved to be a bustling center of artisans and workers. Workshops of potters, weavers, goldsmiths and leatherworkers alternated with kilns and amulet workshops, while administrative buildings regulated production. Dwellings, courtyards and a large artificial lake returned the image of an industrious and orderly place, suddenly abandoned, perhaps during Akhenaten’s religious reform. Thus, a gilded wooden chair belonging to Princess Sitamon emerges in the center of the room, around which small models, molds and jewelry are arranged along the walls in display cases. Tangible demonstrations of everyday life, work, but also the grace and elegance that permeated every aspect of Egyptian life.

The ninth room is dedicated to religion in Ancient Egypt, a theme that emerges in a space with dark and solemn tones, evoking the sacredness of the relationship between man and the divine. Egyptian religion, among the oldest and most complex in history, was based on a deep connection with nature and the country’s geography. All natural elements-the sun, the wind, the flood of the Nile, the desert-were perceived as manifestations of a divine force. From the vision arose a polytheistic system populated by countless deities, each guardian of an aspect of human life and values such as justice, loyalty, love and truth.

Worship was expressed in temples, the spiritual and political centers of Egyptian civilization, where priests and priestesses offered rites, offered gifts and marked the days with sacred ceremonies. The size and magnificence of the shrines varied according to the importance of the deity to whom they were dedicated. Major figures in the pantheon, such as Ra, god of the sun, or Ptah, protector of craftsmen, embodied the principles of creation, while the myths of Osiris, Isis, and Horus shaped the Egyptian conception of kingship and rebirth. Religion was moral and social order: the performance of rituals guaranteed prosperity, health and protection for individuals and the community.

This is the context for the section on cube statues, commemorative sculptures that originated in the Middle Kingdom and spread throughout the Pharaonic civilization. The depictions show the worshipper seated on the ground, arms wrapping around the knees, in a collected pose that expresses submission and piety. In addition, the polished surfaces of the statues present space for inscriptions and offering formulas. In 1903, French archaeologist Georges Legrain unearthed more than three hundred of them in the cachette (a secret hiding place) of the Karnak temple, including the statue of Ankhunnefer, wrapped in a monolithic robe and inscribed with funerary texts. Standing out in the center of the room is the lid of Senqed’s sarcophagus, made of black granite and dating from the end of the 18th Dynasty. The layout follows the same principle as the first rooms: the works breathe, illuminated in a way that enhances the strength of the forms and materials. Notable exhibits include a painted limestone slab depicting Akhenaten and his family worshipping the god Aton, a kneeling statue of Queen Hatshepsut in red granite, and a statue of Ramesses VI next to the god Amun.

We approach the last room, where the tour concludes with a reflection on the concept of kingship, expressed through one of the most intriguing works in the entire exhibition: the funerary mask of Amenemope, made of gold and cartonnage during the 21st Dynasty, in the Third Intermediate Period. Its golden splendor sums up the very essence of the sacred power of the pharaoh, a figure at once divine and earthly.

From the very origins of Egyptian civilization, around 3200 BCE, kingship was understood as a direct emanation of the divine. The ruler embodied Horus, the god who had regained the throne from his father Osiris, and as such was guardian of the cosmic order and defender of Egypt. His power was based on the principle of maat, truth, justice and universal harmony, and at the moment of death he assumed the nature of Osiris, thus perpetuating the cycle of rebirth. The son of the solar god Ra, the pharaoh had to prove his greatness by incredible feats: the building of temples for example, but also pyramids and canals, or expeditions to distant lands such as Punt, from which came precious and symbolic goods. Here, everything he accomplished was honored as a miraculous act, a sign of his divine nature. Pharaoh thus combined in himself every form of authority, religious, political, military and administrative, and even the fertility of the land or the floods of the Nile were seen as reflections of his life force. Kingship, therefore, was seen as a cosmic principle that regulated the entire world order, capable of influencing art, architecture, literature and religion.

Amenemope, son of Psusennes I, reigned for a short period devoid of major monumental achievements. During his rule, the growing influence of Amun’s priests in the south led to a gradual fragmentation of power, a prelude to the political crisis that would mark the later XXII Dynasty. In any case, the discovery of his intact tomb by archaeologist Pierre Montet in 1940 restored the ruler to a prominent place in Egyptian history, thanks to the incredibly beautiful funerary equipment. Next to the mask of Amenemope stand two presences that complete the scene: a triad of Mycerinus, a demonstration of the Old Kingdom and its balanced and solemn art, and a granite statue of Pharaoh Thutmosi III next to the god Amun, a symbol of the regal force that binds man to the divine. Together, the three works create a silent sanctuary of power and immortality, a prelude to thefinal chapter of the exhibition itinerary.

A short distance away, a singular work closes the exhibition. It is the Isiac Canteen, a bronze table documenting Egypt’s fortunes in the Western imagination, which came on loan from the Egyptian Museum in Turin. Dating from between the first century B.C. and the fifth century A.D., and probably coming from Rome’s Iseum Campense (the Temple of Isis in Campo Marzio), the table reproduces Egyptian religious motifs reinterpreted in a Greco-Roman key. Pseudo-geroglyphic columns divide the surface into registers populated by divine figures, including Isis seated on a throne, surrounded by symbols of the union between Upper and Lower Egypt and scenes of votive offerings. It was purchased in the 16th century by humanist Pietro Bembo, who saved it after the sack of Rome in 1527.

The exhibition Treasures of the Pharaohs thus unfolds as an endless cycle. The journey starts from above, amid images of the death and afterlife of the ruler, then descends into the earthly world of the king’s daily life and people, and finally ascends to the religious dimension that seals the tale. What can be felt in the halls is the Egyptians’ desire to go beyond time and make their existence immortal. The Egypt of the pharaohs continues to speak to us because of its incredible ability to transform memory into material objects and, at the same time, to imprint matter with memory itself. And it is precisely in that gold that does not corrupt, in the light that vibrates on the masks, that it is possible to express a question: what remains of us when time expires? The exhibition is sublime, solemn, seductive because it knows how to speak to the most intimate part of the human being, to the regal and noble part that has always belonged to us. Treasures of the Pharaohs thus speaks to the soul and does so through the body and voice of the gods.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.