It is surprising that there is little or no talk in Italy about the muscular exhibition that the Louvre has organized to reconstruct the story of Jacques-Louis David exactly two hundred years after his death. In terms of completeness and volume of material, it is an exhibition that will be difficult to see again in the short- or medium-term future: it is then true that the bulk of David’s important works are already in the Louvre, but for the 200th anniversary exhibition the three curators, Sébastien Allard, Côme Fabre and Aude Gobet, gathered almost everything that could be brought to the halls of the Hall Napoléon. Of course: David is painter who, under the Alps, does not ignite enthusiasm. In our parts, he left nothing behind and is considered a sort of director of Napoleonic propaganda, the painter of the empire, the inventor of the iconographic apparatus of a regime that inflicted on Italy the trauma of spoliation: yet he is an artist who, one could say, almost single-handedly embodies a fundamental moment in European history. What’s more, the exhibition, titled simply Jacques-Louis David, aims to offer a substantially new, or at least different, perspective on what has been said about David so far: the underlying thesis is that his works are “imbued with feeling more than the imposing rigor of his canvases might suggest,” and on this basis an exhibition dedicated to bringing out David’s ideas and personality through the force of his paintings has been set up. An exhibition, then, of politics perhaps even before art, so much so that right from the introductory panel it is explained to the public that the visiting itinerary intends to dispense with the adjective “neoclassical” to qualify David’s art, in order to avoid any conditioning, any opening, even minimal, to the idea of a David caged in a rigid, repetitive, glacial formalism.

The thesis probably presupposes a pejorative and, in some ways, perhaps even a limiting conception of the term, if from the outset David’s ideas and his war on academicism are adduced as elements that clash with art-historical conventions, but it is nonetheless undeniable that David’s recovery of the classical would not have been possible without a convinced, strong, passionate adherence to the strict theory of’an art endowed with civic and moral functions, an art that eschewed any complacency and took upon itself the Enlightenment mission of transferring to the relative an ethical model that, after 1789, would become a revolutionary ideal of democratic edification of the public expressed by means of recourse to the antique. However, it would be extremely reductive to think that only one neoclassicism existed (and even more reductive to make it coincide with Enlightenment and pre-Revolutionary neoclassicism), and David himself, after all, embodied several souls of it, so much so that paradoxically one might come to the conclusion that this peintre engagé, as he is called in the exhibition, is perhaps the most neoclassical artist who ever existed. Or, alternatively, that the theoretical construction of so-called “neoclassicism” no longer responds to up-to-date reading criteria and is to be dismantled, razed to the ground, torn down to the foundations in order to replace it with something else. With what, however, it is not known, nor in any case is this the intent of the exhibition, which does not cultivate the aspiration of writing a new theory of neoclassicism, but merely subtracts David from the textbook categorizations that might deflect the reading offered by the exhibition.

To support it, the two curators have assembled a hundred or so works, divided along a dozen sections (in addition to the squares that have not been moved from the Salle Daru, namely The Brute, Leonidas at Thermopylae , and The Coronation of Napoleon, and which are to be considered integral parts of the exhibition, not least because the views are the same and in the Hall Napoléon there are precise signs inviting the public to continue the visit upstairs) that accompany visitors throughout Jacques-Louis David’s career, from his beginnings in Rome to his exile in Brussels: large rooms, almost always correct lighting, captions commenting on each work, and a large audience, especially in the first rooms, where uninterested tourists are concentrated (or who come to the exhibition to see the Oath of the Horatii) who start out concentrated and then, from halfway through, slip away toward the exit, leaving in the last rooms the visitors who entered the Louvre specifically to see the exhibition. And who, in any case, are many, and not only because the French are fond of David: the Louvre exhibition is the first monographic devoted to the painter since 1989, so it is fair to expect a particularly crowded show, despite the large, suitable, well-lit spaces. We are not at the levels of the gigantic exhibition that was held thirty-six years ago, part at the Louvre and part at the Palace of Versailles (and which was a once-in-a-lifetime occasion: there were more than two hundred works, and a catalog of nearly seven hundred pages was produced for the occasion), and yet, given the current lean exhibition times, the current show is among the best and biggest things that can now be seen in Europe.

Unlike the current one, the 1989 exhibition lingered much more on the youthful phase of David’s career, which was explored in two sections out of the six that made up the itinerary: now, however, everything is summarized in a single chapter that traces the story of David’s artistic debut. A difficult debut, the curators tell us, since the painter, who grew up at the time of the waning of the monarchy and the eclipse of great Rococo painting, struggled to find “a path congenial to him.” the main shortcoming of this section, which is perhaps the weakest in the exhibition, lies in its excessive speed, since we are hastily presented with a painter who was 25 years old, and therefore mature for the time, and who already appears routed on a recognizable path, while the paintings closest to those of his master Joseph-Marie Vien (who, moreover, is not represented in the exhibition, although there is no shortage of comparative works), that is, those where David’s fledgling classicism presents more points of contact with the rococo, are almost completely missing. The only exception is the painting that opens the exhibition, the Death of Seneca, which seems almost an equally theatrical but more controlled translation of Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s Coreso sacrificing himself to save Calliroe , a work from eight years earlier that is kept in the Louvre but was not brought to the exhibition (a pity, because it would have been a timely comparison). With the later Erasistratus discovers the cause of Antiochus’s illness, from 1774, a year after the Death of Seneca, we are already dealing with a more restrained David who is already working out a language close to that of his maturity, although there is no shortage, even in the following years, of intense moments of reflection on seventeenth-century art: St. Roch asking the intercession of the Virgin for the healing of the plague victims, a work from 1780, painted in Rome and on loan from the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Marseille, preserves a realism with a marked Caravaggesque imprint, here mixed with Poussinian and Guercinian cues, as does the coeval Saint Jerome that arrived on loan from Québec, mindful of the paintings of José de Ribera, whom David had met during his study stay in Rome between 1775 and 1780.

By the time he returned from the urbe, David was already a mature painter, a painter who was “burning the candle at the seams,” to use the title of the second section of the exhibition, which opens with the aforementioned San Rocco and continues with several works that attempt to mediate between Poussin’s composure and Caravaggio’s naturalism and return us to the more theatrical, more dramatic, more sentimental, such as the one we can admire in Belisarius begging for alms (a work from 1781, so successful that it was later replicated: a second, smaller version is also in the exhibition), which tells the story of the 6th-century Byzantine general who was the victim of an injustice by Emperor Justinian, who had him blinded and effectively condemned him to having to live by begging foralms, or in one of the most moving works of his production, the Sorrow of Andromache, a painting that sticks in the memory for the desperate gaze of Hector’s wife mourning her husband, killed in battle by Achilles, and for the gesture of her son Astianactes caressing her chest. The section culminates with the entire wall dedicated to the Oath of the Horatii, among David’s masterpieces, a work with which the artist positions himself as a renewer of painting, through a language of simple but rigorous compositions marked out according to clearly recognizable geometries (here, all visual directions converge on the hand of the father of the Horatii to emphasize the solemnity of the oath), horizontal progression in imitation of ancient bas-reliefs, uncrowded scenes, precise drawing and sharp modeling, ease of reading, restrained and well-smoothed coloring, and cool, crystalline light. Then there is in David a perfect adherence between form and content, between this icy geometry, warmed, however, by the determination of gestures, and its content of open political significance, an exaltation of civic virtues and of theattachment to the homeland in the context of a commission that David had received from the French crown through the Comte d’Angivillier, at the time director general of the Bâtiments du Roi, the body that presided over the works ordered by the king of France in his residences.

The Oath of the Horatii is the first work in which the artist does not try to latch onto an earlier tradition: here, David stops looking backward and begins to invent. And he invents a rigorous, severe painting that is easy to read but at the same time refuses to be illustrative, since David’s aim is not to narrate or explain, but to “invite reflection,” as the curators suggest. And as a reformer he was perceived, moreover, by his contemporaries: after the exhibition of the Oath of the Horatii, he was called the “regenerator of painting” at the Salon, an appellation he earned not only for the language he had coined and would impose (including in works for his private patrons, who from the Oath onward began to swarm to his atelier to obtain one of his paintings: the Loves of Helen and Paris, of which the exhibition displays two variants, are a demonstration of how David sought to apply the principles of his painting even to the most frivolous subjects), but also for his way of charging the antique with unprecedented meanings. Even the lunge on portraiture (there are masterpieces such as the Portrait of Doctor Alphonse Leroy and the Portrait of Geneviève Jacqueline Pécoul) is a way of connoting in a political sense theart of David, since the painter is presented in the exhibition as the artist of the “enlightened bourgeoisie,” of that social class favorable to the ideals of renewal that would light the fuse of the French Revolution. David’s portraits are, in some ways, minimalist: a neutral background, every frill eliminated, there is an emphasis above all on the pose and the gaze of the effigy.

David himself, who began to take an interest in active politics, adhered wholeheartedly to the French Revolution and even held political roles, anticipated by a certain activism, we would say today: in September 1789 he had placed himself at the head of the movement of the “Dissident Academicians” who intended to reform artistic institutions, and the following year he was at the head of the Commune des Arts, the group that was officially formed as a result of that movement’s experience (David would later succeed in obtaining, in 1793, the suppression of all academies: meanwhile, in 1791, he was among the signatories of the petition calling for the deposition of King Louis XVI, and that same year he ran for deputy, but failed to be elected). A couple of sections of the exhibition thus explore David’s contribution to the iconography of the Revolution: a significant space is devoted to the Oath of the Pallacord, of which both the large, almost seven-meter unfinished canvas, on loan from the National Museum in Versailles, and the drawing that served as a model for a print offered for sale in order to raise resources to be used for the creation of the large-scale work are on display. David’s drastic volte-face, who even in 1789, while still frequenting bourgeois circles pushing for instances of renewal, was nonetheless also close to the aristocracy and perfectly integrated into the institutions of the monarchy, is not explored in depth in the exhibition, especially since, as the Revolution deflagrated, the artist was busy on his Brutus, another painting commissioned by the Bâtiments du Roi. The point, Antoine Schnapper already noted in the 1989 major exhibition catalog, is that we do not know, nor will we ever know, what David’s views really were at the start of the Revolution. One of the few certain elements is that the artist would have tried to retroactively pad his paintings with meanings that conformed to revolutionary ideals: after the fall of Robespierre, of whom David had been a supporter, and the consequent end of the regime of the Terror, the painter was also put on trial, and in the speech he wrote to defend himself he invited the deputies of the Convention, from which, moreover, he had been expelled, to judge "whether he who must have been imbued with all the beauty and sublimity of virtue in painting the dying Socrates, of the heroic enthusiasm inspired by love of country to worthily express the generous dedication of the three Horatii, of the supernatural courage which the horror of tyranny bestows on free men [...] could have participated in a conspiracy that would have plunged his country back into the misfortunes of servitude." However, it is also true that, in all likelihood, this reading of his pre-revolutionary paintings was the result of calculation at a time when the artist was risking his life (he was eventually imprisoned but his case was dismissed: once again placed under surveillance, he was then finally amnestied and from 1795 onwards he abandoned active politics and devoted himself solely to art): David, however, had always been quite critical of artistic institutions even before the Revolution, so it is entirely likely that his political ideas had matured in a context of impatience with academia and then led him to a much more extensive engagement than perhaps he himself might have imagined.

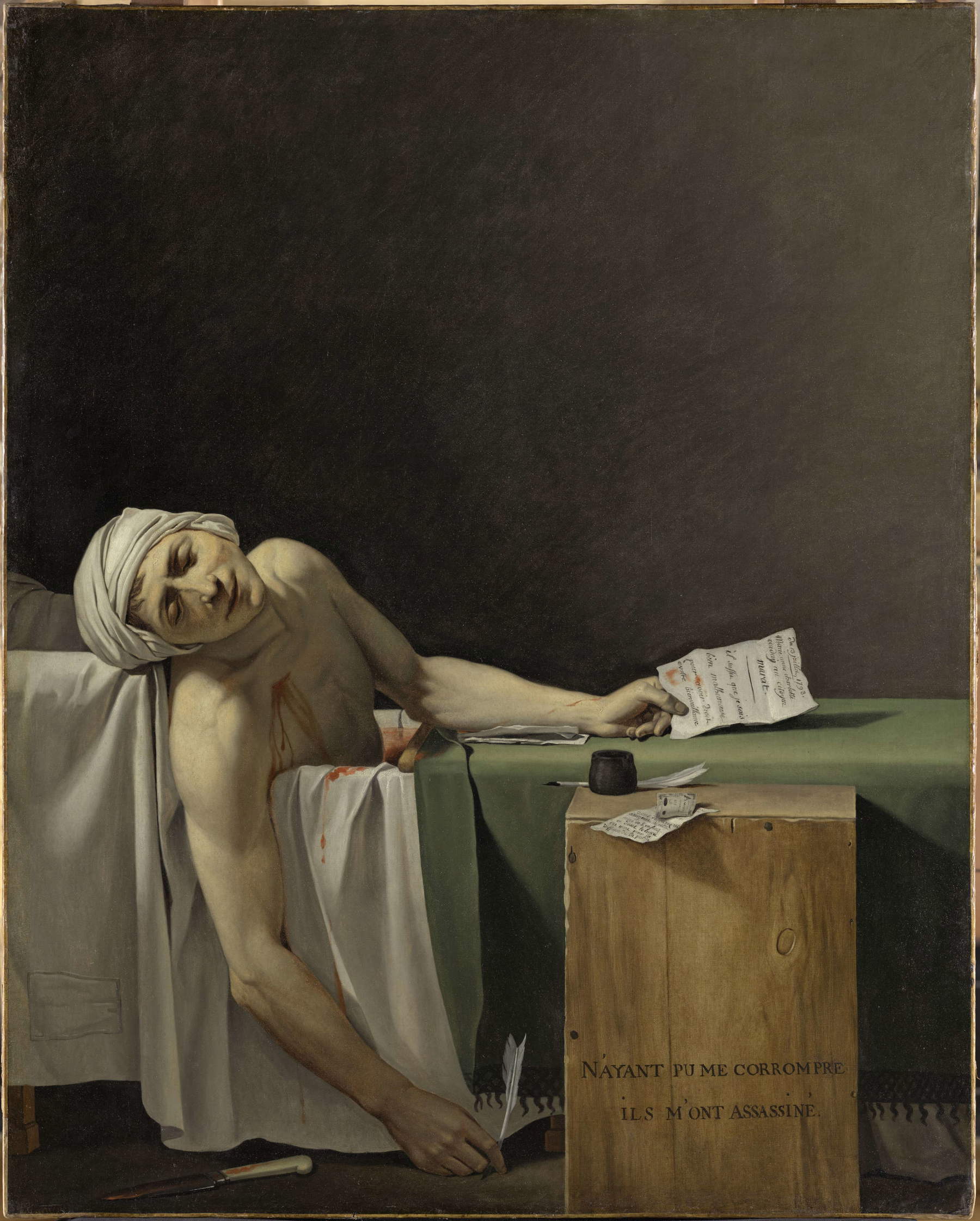

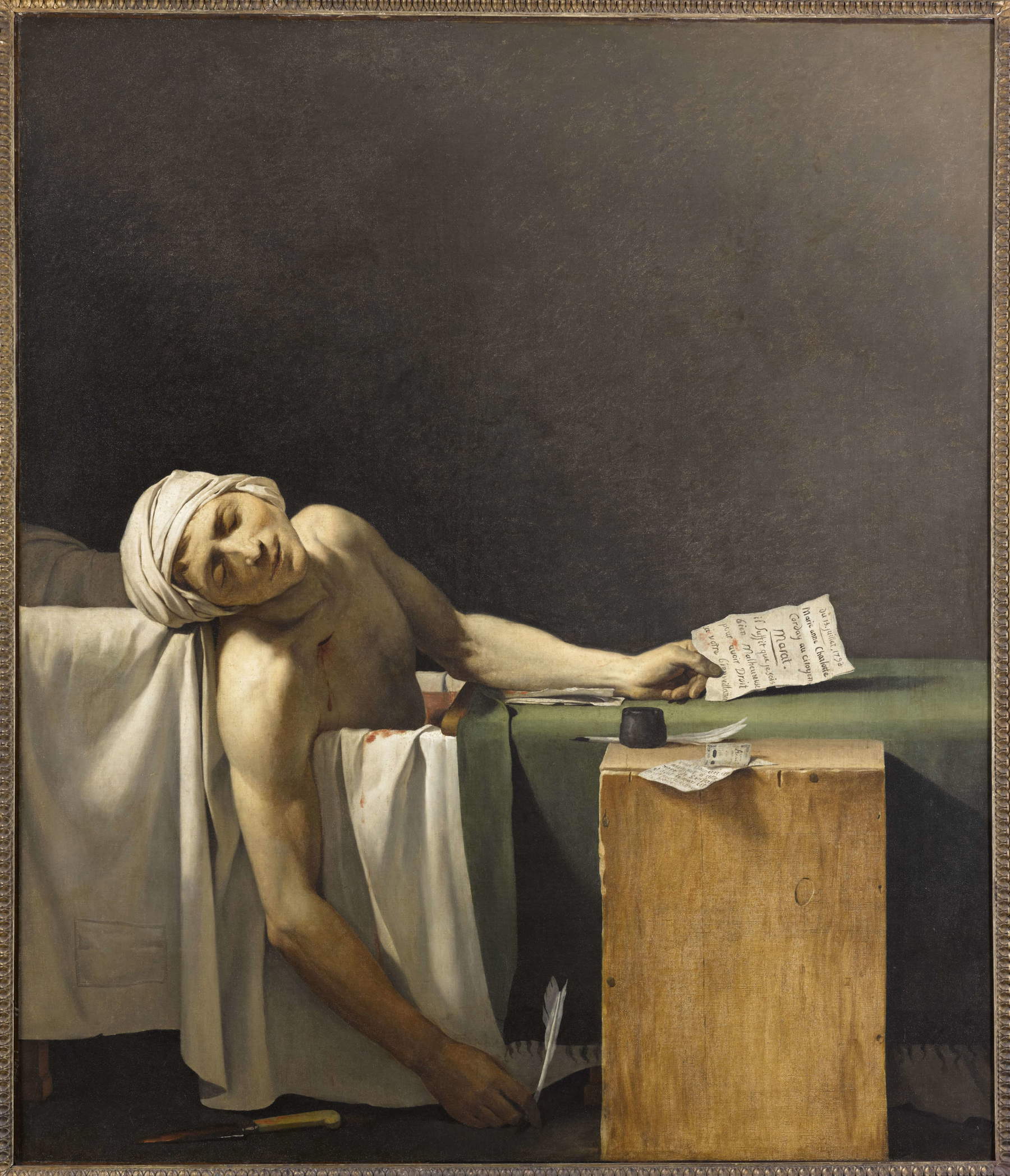

His manner, however, did not change: the Oath of the Pallacorda eloquently demonstrates how David used the same formal language as the Oath of the Horatii, thus of a painting commissioned by the monarchists, to show not only a topical fact, but a founding moment of the new national unity (the large canvas now in Versailles was, moreover, intended for the room in which the meetings of the Constituent Assembly were to be held). It is from this juncture that David is no longer just a painter of history but becomes a painter of the immediate. And it is also in his activity as an artist that his political commitment is substantiated. At the height of his career as a revolutionary, David had been appointed a member of the Committee of General Security (it was 1793 and the regime of the Terror was in force), and in this capacity he was a co-signer of dozens of arrest warrants that would later lead to the execution of many people also close to him, and in January 1794 he was, for a couple of weeks, also president of the National Convention, the legislative and executive body of the Revolution. He was also a member of the Committee of Public Instruction, was responsible for designing the uniforms of the public authorities and organizing the new festivities of republican France, and above all invented the symbols of a new “civic religion,” as it is called in the exhibition, which were constructed with the solemn language of history painting applied to episodes of close relevance. The Death of Marat, of which the original exhibited in Brussels and two replicas can be seen in the exhibition, is to be explained in this sense: David does not choose to depict the moment of Jean-Paul Marat’s assassination at the hands of Charlotte Corday, but prefers to show the relative the “Ami du peuple” already lifeless, lying inside his bathtub, like a Christ in the tomb (the artist had called to mind all the seventeenth-century he had seen in Italy, Caravaggio in the lead). And the same goes for the Death of the Young Coffin, caught in the last moment of life, naked like Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson’sEndymion to whom he is juxtaposed in the exhibition and from whom perhaps David was inspired to construct the image of the 14-year-old martyr killed by the royalists, destined, in the painter’s ideas, to become a symbol of the atrocities committed by the enemies of the Revolution.

Among the few supporters of Robespierre who survived the end of the Reign of Terror, David, while awaiting the final amnesty that would come in 1795, had meanwhile returned to portraiture (on display are the two magnificent portraits of his sister-in-law Émilie Pécoul and her husband Pierre Sériziat, both executed at that time, as well as the fascinating portrait of Henriette de Verninac, which is instead from 1798-1799), and would soon resume painting large history pictures: with the Sabine women, painted on his own initiative, David had sought to further renew the genre with the intention of returning to a history painting moved by the search for an ideal beauty that could rise to allegory, in this case of unity and reconciliation (the episode described by David is that of the Sabine women trying to stop the war between Romans and Sabines, that is, between husbands and brothers). It is only a moment, however, for throughout the early part of the nineteenth century the artist would return to the formula he had experimented with during the Revolution, to that mixture of classical language and contemporary subject matter, in order to construct the iconography of Napoleon, an iconography of which all the best-known examples are paraded in the exhibition: the Napoleon at the Great St. Bernard Pass, the Napoleon in the studio, the Napoleon in emperor’s robes. We are accustomed to thinking of David as Napoleon’s premier peintre , a rhetorical and triumphalist Bonapartean painter, a faithful glorifier of the emperor. In reality, the relationship between the two was far more ambiguous and difficult than images would suggest. A relationship, Schnapper wrote, “marked more by failures than triumphs, and the painter deserves some credit for showing such loyalty to the emperor.” The scholar had pointed out that some of David’s most important paintings, such as the Belisarius or the Sabine Women, were made outside of any commission, even though the artist hoped to sell them to the state: many paintings requested by Napoleon were instead executed without a formal engagement, without the price being set in writing. The history of David’s relations with the cumbersome imperial bureaucracy is marked by the frustrations of an artist who often struggled for recognition and gratification, to the point of leaving, as early as 1805, the role of Napoleon’s official portrait painter to his pupil François Gérard, after Napoleon had turned down the painting in the guise of the emperor that closes the section (so much so that, despite a working relationship that worked for fifteen years, and despite the fact that David had in fact become an instrument of Napoleonic propaganda, there are no official portraits of Napoleon executed by David). It is no accident that the exhibition suggests to the visitor that the relationship between David and Napoleon should be reread in light of the “question of the artist’s freedom in the face of power and its administration.”

After the fall of the empire, David suffered a new and final setback: with the Restoration he was condemned to exile, as he was among the revolutionaries who voted in favor of Louis XVI’s death sentence in 1793. Taking refuge in Brussels, where he died in 1825, the painter continued to defend his idea of an art in which ideal beauty was put at the service of a political project. Allard, Fabre and Godet, in the exhibition’s finale, offer an exquisitely political reading of all the works, even those seemingly furthest removed from politics, even those imbued with warm eroticism, such asCupid and Psyche on loan from the Cleveland Museum of Art, read in the light of a possible double warning (the first: since the world is corroded by flatness and vulgarity, we might as well go back to fairy tales; the second: even the fairy tale, in spite of everything, is after all a crude story of sex between two teenagers, and as such it is represented, without disguises and without pretenses), or like Mars disarmed by Venus and the Graces, a work of 1824 which is to be considered, according to the curators, not only an anticipation of kitsch (in the exhibition it is jupiter and Thetis by Ingres of 1811 to highlight the affinities of language), but also a kind of artistic testament, the protest of a painter who probably saw the political dimension of art disappearing in the name of an end in itself beauty that could not meet his ideas. The final conclusion is that David, even in his last works, is not “the cold star of scholastic manuals” but should rather be considered “a man who developed a language to address his age,” and that is why he is so profoundly relevant.

While the 1989 major exhibition had favored completeness, the current one prefers density: the visitor will find in the Hall Napoléon of the Louvre an exhibition not much larger than in many other recent exhibition occasions, but he will find an exhibition of a density difficult, rare, extreme, a density capable, despite the not even so high number of works on display (just over a hundred), of making him spend even an entire afternoon between the various rooms without him even noticing. The main problem with this exhibition lies, paradoxically, in its foundation: that is, one has to wonder whether the project of scrutinizing the political David actually says anything new. If one arrives at the exhibition without knowing its trajectory (both artistic and political), one will have material to leave the Louvre satisfied. If, however, one seeks to discover something that has never been said, then perhaps one will experience some disappointment, since the only results the exhibition can offer are just a few suggestions. It is true that David’s art is inseparable from his convictions, his ideas, his action as a politician: but this awareness is nothing new.

The programmatic intent of the exhibition was supposed to be to address the “question of the artist’s engagement in a time of crisis, of art’s capacity to act on society and the ways in which it can do so.” It remains, to be sure, an exhibition that is certainly impeccable, if you will, even courageous in its refusal to attach to David the label of “neoclassical” (a term that, moreover, is never used throughout the tour itinerary), scientifically sound and, given the quantity and quality of works on display, very difficult to repeat, at least on a predictable horizon. And yet, it is an exhibition that reveals some excessive timidity precisely in presenting the figure of Jacques-Louis David in the light of his political commitment, and the idea of imposing him as an artist “for our times” remains just a cue that can be read between the lines of a sequence of masterpieces ordered along a route that in the end will appear infinitely more formalist than the introduction suggested. David, if one wants to attribute to him a political role to be identified with a single word, was a filmmaker, and not an ideologue: then perhaps, in order to find a David to be read through the lens of “our times,” the exhibition should have insisted more on the implications of the intrusiveness, scope, and goals of his direction. In the end, probably the most interesting aspect of the whole thing are the doubts that remain with the visitor after probing the entire sampler of David’s contradictions, the contradictions of the man, even before the artist. Of the man who all his life had regarded his painting as a means of changing the world. And for a few years he really had a chance to change it, concretely. What did he achieve?

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.