It could have been titled Les Italiens de Paris the Belle Époque exhibition currently running at Palazzo Blu in Pisa until April 7, 2026, and indeed the subtitle reads “Italian Painters in Paris in the Age of Impressionism.” In fact, the protagonists of this long and articulated exhibition curated by Francesca Dini are mainly Giovanni Boldini, Giuseppe De Nittis and Federico Zandomeneghi, that is, the three artists considered among the greatest Italiens de Paris, who between the 1870s and the first decade of the 20th century elected the French capital as the ideal place to evolve their art and their way of painting toward modernity, for it was in Paris that in those years they began to breathe a new air, an air of elegance, the worldliness of a bourgeoisie that was increasingly urbanizing with the consequent improvement of their living standards. A bourgeoisie that frequented the salons, cafés, and theaters, strolled along the boulevards, and took an active part in the extraordinary cultural wave that had swept through the Ville Lumière of that time, during which Paris became the true nerve center of Europe. The pleasant and seemingly frivolous life of the bourgeois class was therefore welcomed among the subjects most depicted by these artists, who brought the spirit of the time into their canvases, but this choice was in the past seen as a kind of betrayal by the Italian artists in Paris to their cultural origins in order to meet the favor of the Parisian market. The stated objective of the exhibition in the introduction of the accompanying catalog is thus “to evaluate the stylistic mutations of Boldini, De Nittis and Zandomeneghi and the synergies that arose from their encounters with other eminent European artists dwelling in the French capital,” writes the curator, and “to historicize the role of our valiant painters, in the diversity of their aesthetic choices and path.” From the point of view of content, “are these painters of ours more myopic than the French Impressionists in preferring to portray the pleasant life of the metropolis and its contours?” Or was it perhaps convenient for France, after the disastrous defeat at Sedan, to centralize on itself this depiction of modern metropolis, pleasant life, Belle Époque, in order to regain its lost international prestige?

There would probably have been no Belle Époque without that ruinous French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. And so the Blue Palace exhibition, before letting us revel in the pleasantness and elegance of that happy time (albeit a bourgeois privilege only), lets us breathe in that heavy and tragic air that preceded it, through the nocturne by Carlo Ademollo, a Risorgimento artist-soldier, who depicts three nuns illuminated by lantern light among the bodies still lying on the battlefield on the evening of the Battle of Sedan, through the bodies of the fallen on the palms of martyrdom, with strongly characterized faces, in front of the personification of Paris, standing with the French tricolor in tatters, during the Siege depicted by Ernest Meissonier, and through the corpses lying on the ground in the foreground, including that of a woman, depicted with the greenish complexion of death in Maximilien Luce’s large painting in the Muséd’Orsay that refers to the victims of the Commune.

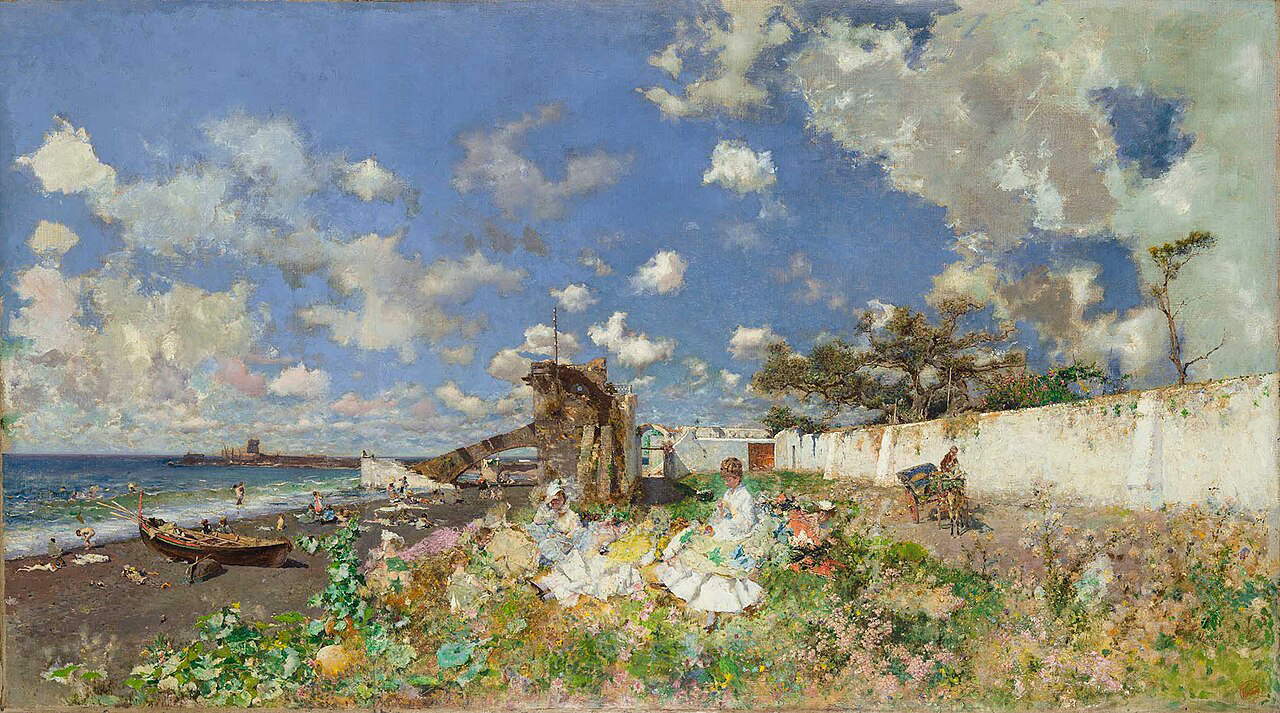

Therefore, the strong contrast between the first and second sections, between the tragic nature of death and the happy era of the Belle Époque, sharply highlighted by the graceful Berthe portrayed by Giovanni Boldini on a bench in a park in the French metropolis, dressed in the latest fashion, with her legs crossed, her gaze turned to the side and her small hand on her chin, whose little finger slips over her half-open mouth in a gesture between innocence and sensuality. A leap in atmosphere that continues with the Return from the Horse Races set on a sunny day at the Bois de Boulogne, a painting by Giuseppe de Nittis that also gives him a way to portray gentlewomen, gentlemen, and children all well-dressed and happy. Did they, therefore, both betray their Italian beginnings in order to “impregnate” themselves? No, they evidently adapted to the times, Francesca Dini points out, they intercepted the desire for lightness of Parisian society animated by joie de vivre and eager to forget the difficult years that had just passed, and each of them thus assumed the role of painter of modern life, or as Baudelaire would say, of the artist flâneur, the man who wanders idly through the city streets, contemplating the landscapes and people he sees in his wanderings and rejoicing in universal life. It is then surprising, as we continue through the exhibition, to see paintings by Boldini that are different from those usually shown in exhibitions, from his typically elegant female figures to wit: a pair of scenes in the Park of Versailles, gallant and leisurely encounters of tiny but detailed figurines, but above all an unusual landscape view of the Strada maestra at Combes-la-Ville, placed in dialogue to highlight its mutual proximity with Spiaggia a Portici by Mariano Fortuny y Marsal (the Catalan was considered in Paris to be the artist of the moment), shown for the first time in Italy on the occasion of this exhibition, and with Il mulino di Castellammare by De Nittis, which had not been seen on display for a long time. A closeness that immediately jumps out at you in the beautiful cloud-populated skies. Boldini’s painting was purchased by the American collector William Hood Stewart, among the most important points of reference in Paris for contemporary art along with the Maison Goupil (the latter a true talent scout for artists, particularly from southern Italy, to impose on the international market, including Alceste Campriani and Antonio Mancini, who are present in the exhibition), and it is therefore likely that Fortuny saw the work from life since Stewart was his patron and was so struck by the “Italian-ness of that Tiepolesco sky” that he reproposed it in his Spiaggia a Portici only a year later.

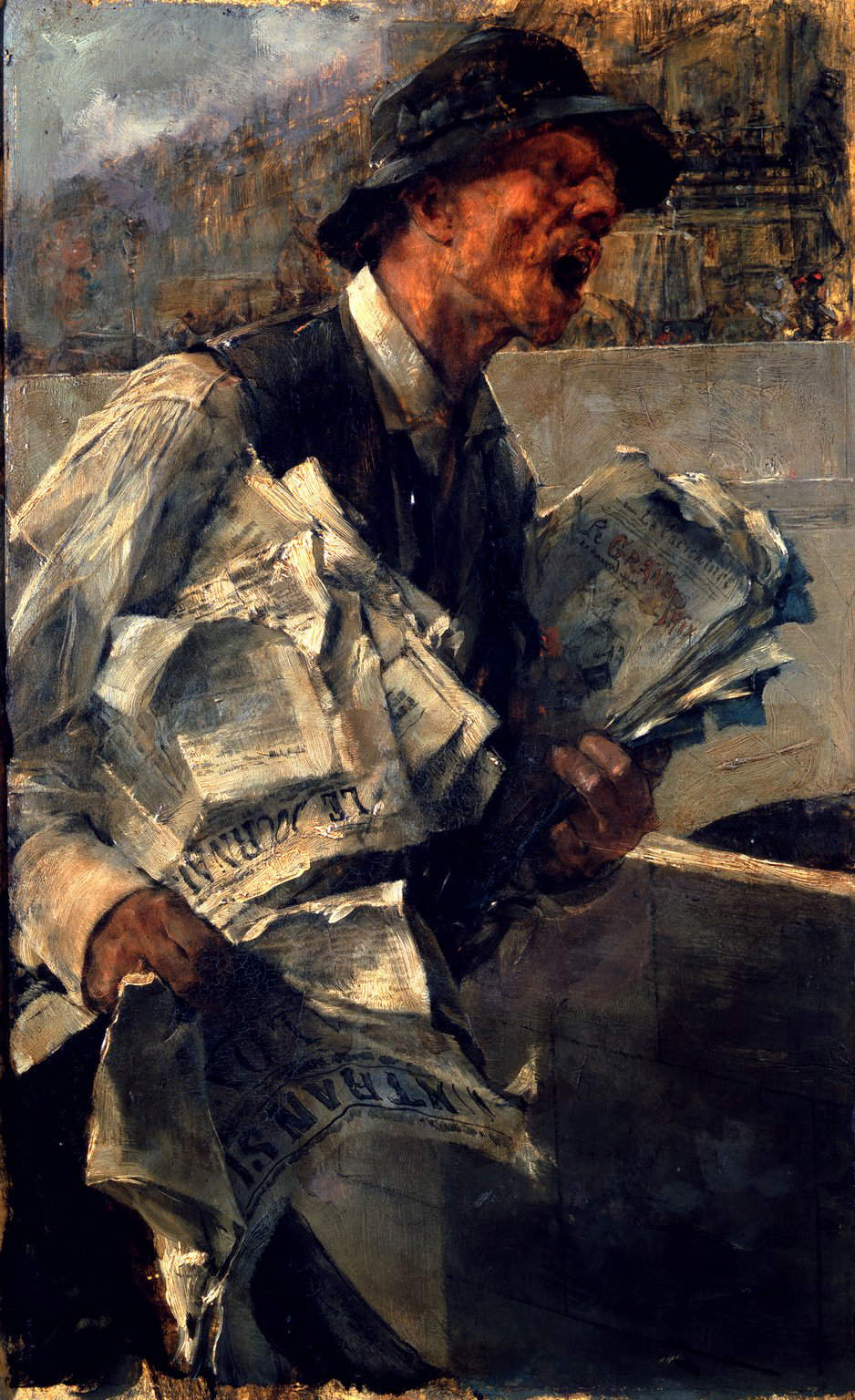

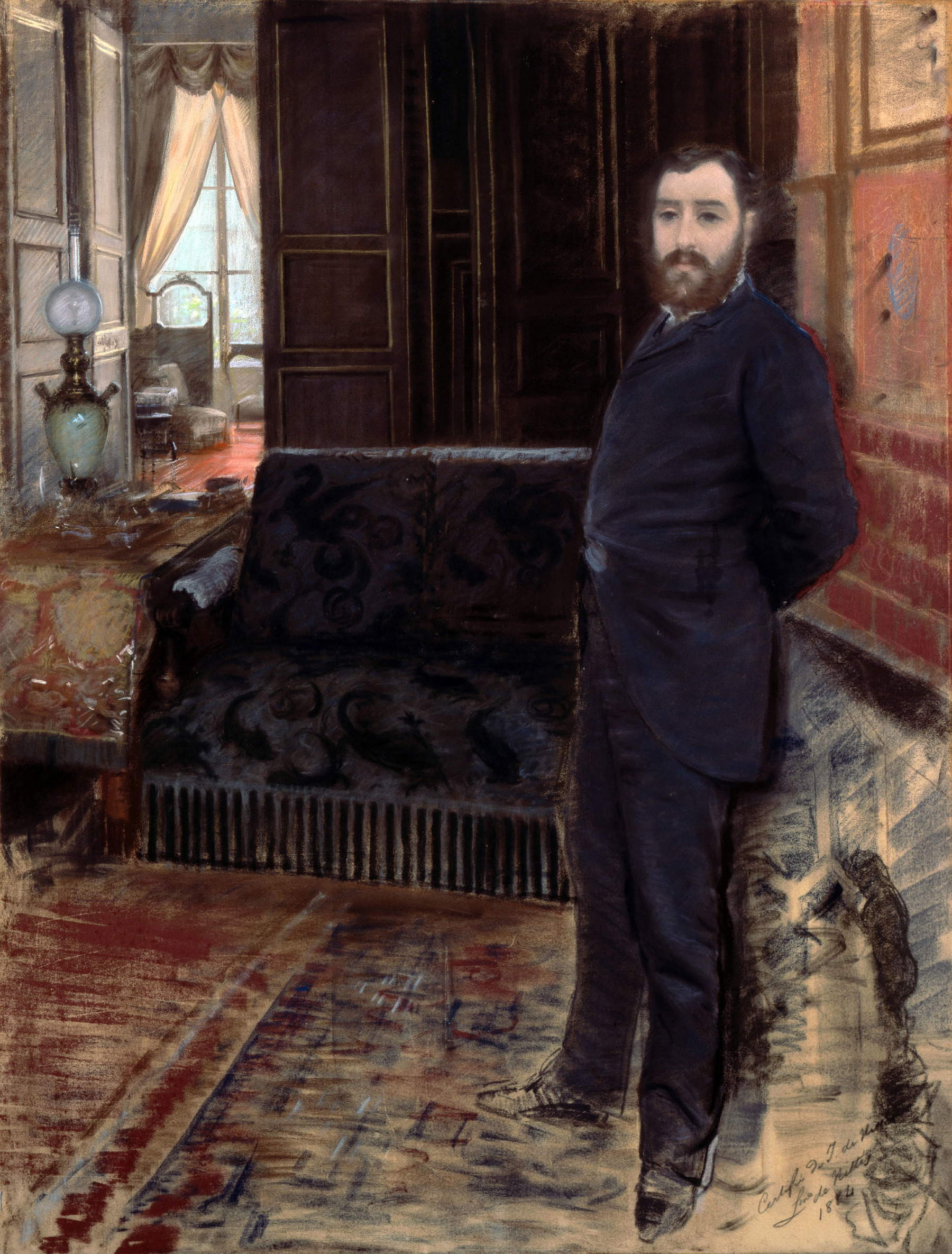

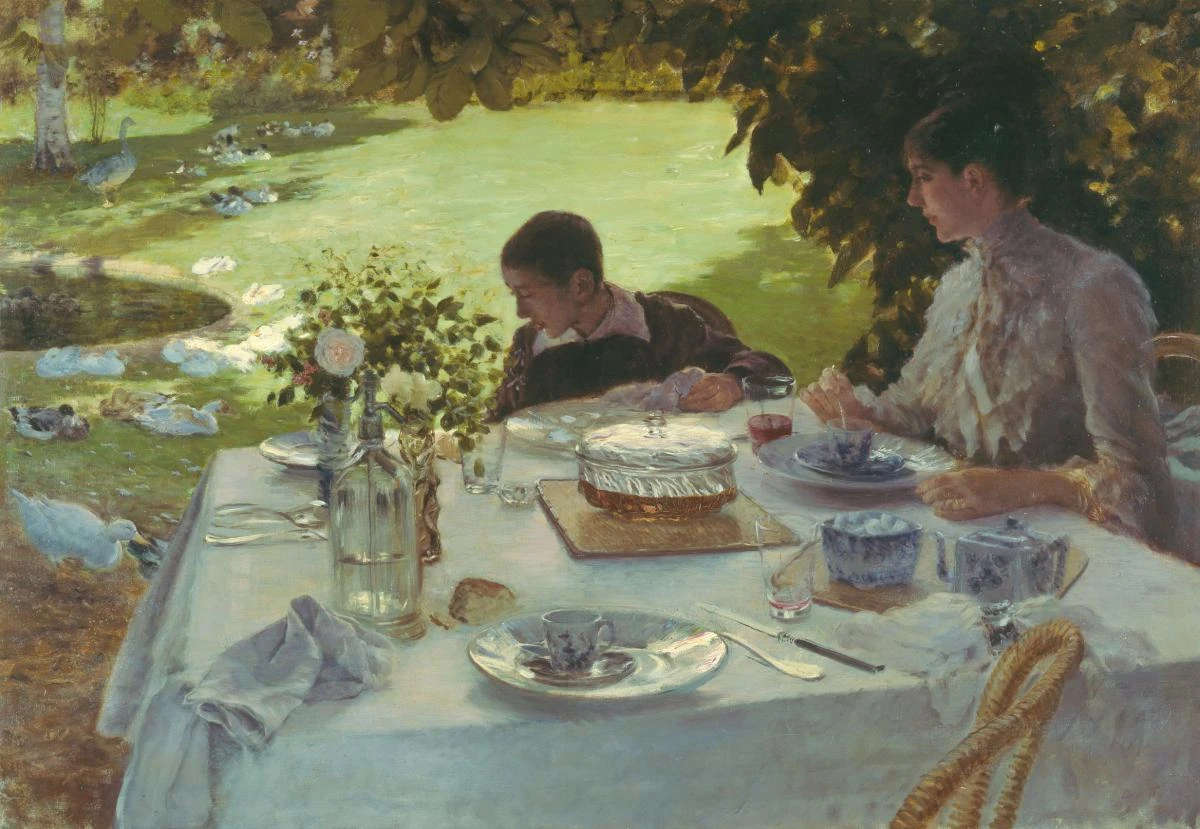

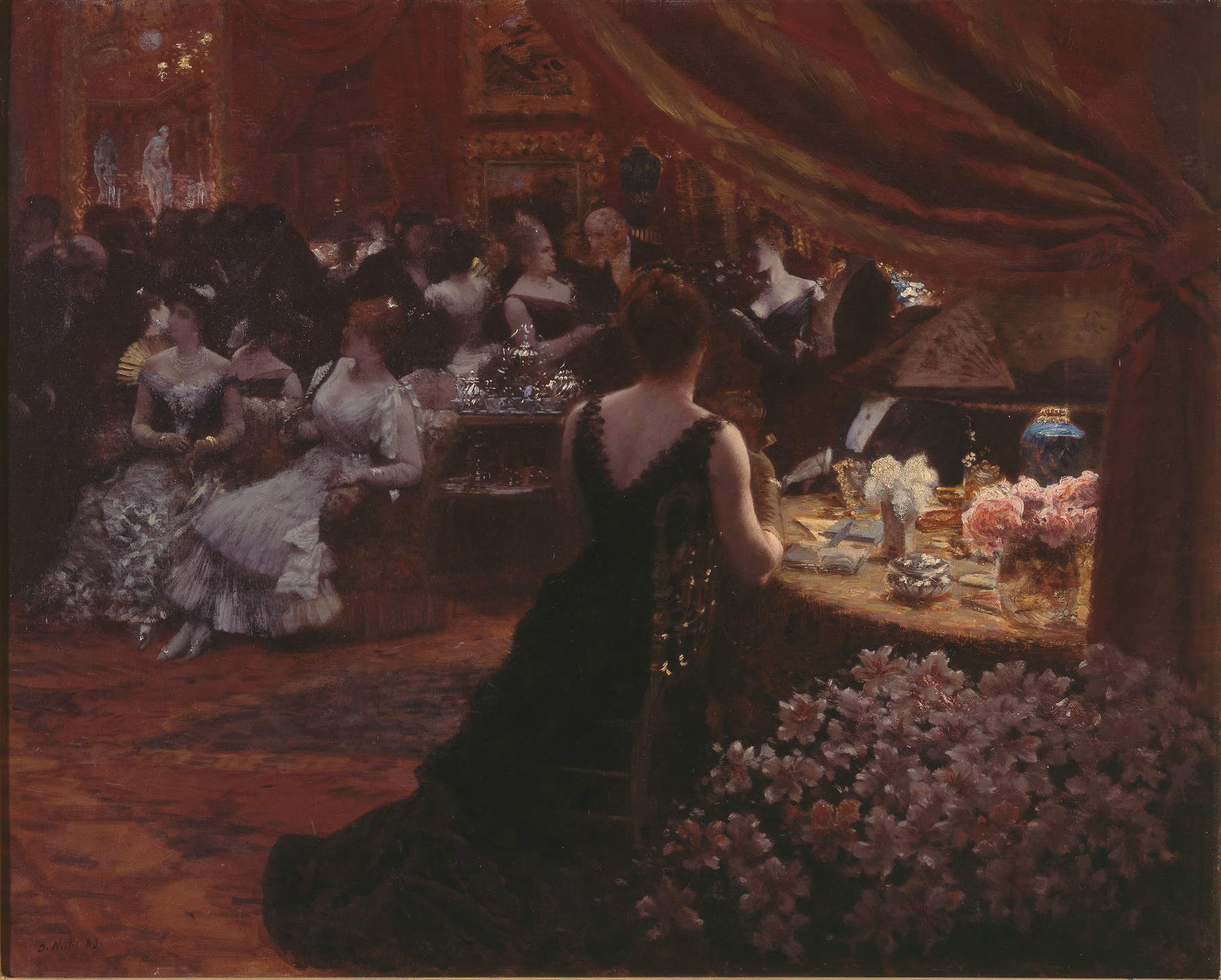

The protagonists of the next two sections are again Boldini and De Nittis: both find inspiration in the reality around them, in keeping with their being painters of modern life, focusing now on views of streets, squares and fields, now on details of everyday life. Examples are Boldini’s washerwomen along the Seine or Berthe walking in the countryside, with her parasol open and her little dog sniffing here and there, and De Nittis’s Al Bois and In the Fields Around London. Each with its own style and inclinations: the former toward the dynamism of the sign and a predilection for portraiture (particularly significant in this sense is Lo strillone of about 1880), the latter toward studies of light that would bring him ever closer toImpressionism (he would in fact participate in the first exhibition of 1874 in the Nadar photographic studio with two studies of Vesuvius), as is already evident from the painting Nei campi intorno a Londra, with its clear Impressionist brushstrokes. De Nittis’ house became a meeting place for many friends, artists, and intellectuals, thanks in part to the good-natured character of the Barletta-born painter and the extraordinary welcome and hospitality of his wife Léontine; it was filled with works of art by his Impressionist friends and japonies, which the artist loved to collect. A splendid selection of paintings from the Pinacoteca De Nittis in Barletta now introduces us to thepainter’s domestic and family universe, where he felt loved and surrounded by the affection of his loved ones, his dear wife Léontine and their son Jacques, from whom an untimely death at only thirty-eight years of age tore him away forever. Prominent among these paintings are a Self-Portrait of the artist, standing in the living room of his home, Léontine seated before a snowy landscape in Effect of Snow, At the Races of Auteuil - On the Chair in which the painter returns to his beloved theme of horse racing, Breakfast in the Garden and On the Hammock in which he focuses on the depiction of the everyday between Jacques and his mother and in which he also has the opportunity to work on the contrast between light and half-light, and The Drawing Room of Princess Mathilde, or Mathilde Bonaparte, a cousin of Napoleon III and niece of Bonaparte, whose salon at the Hotel on the rue de Berri, where the princess lived and received guests surrounded by her collection of artworks, was one of the most coveted drawing rooms in Paris. A painting, the latter, which is very scenic, both because of the wide drapery knotted on the right that opens the view of the elegant salon, at the center of which Princess Mathilde herself is depicted as she stands chatting with her elderly guest, and because of the light that illuminates the round table full of objects and flowers at which the elegant female figure seated with her back to the foreground is leaning.

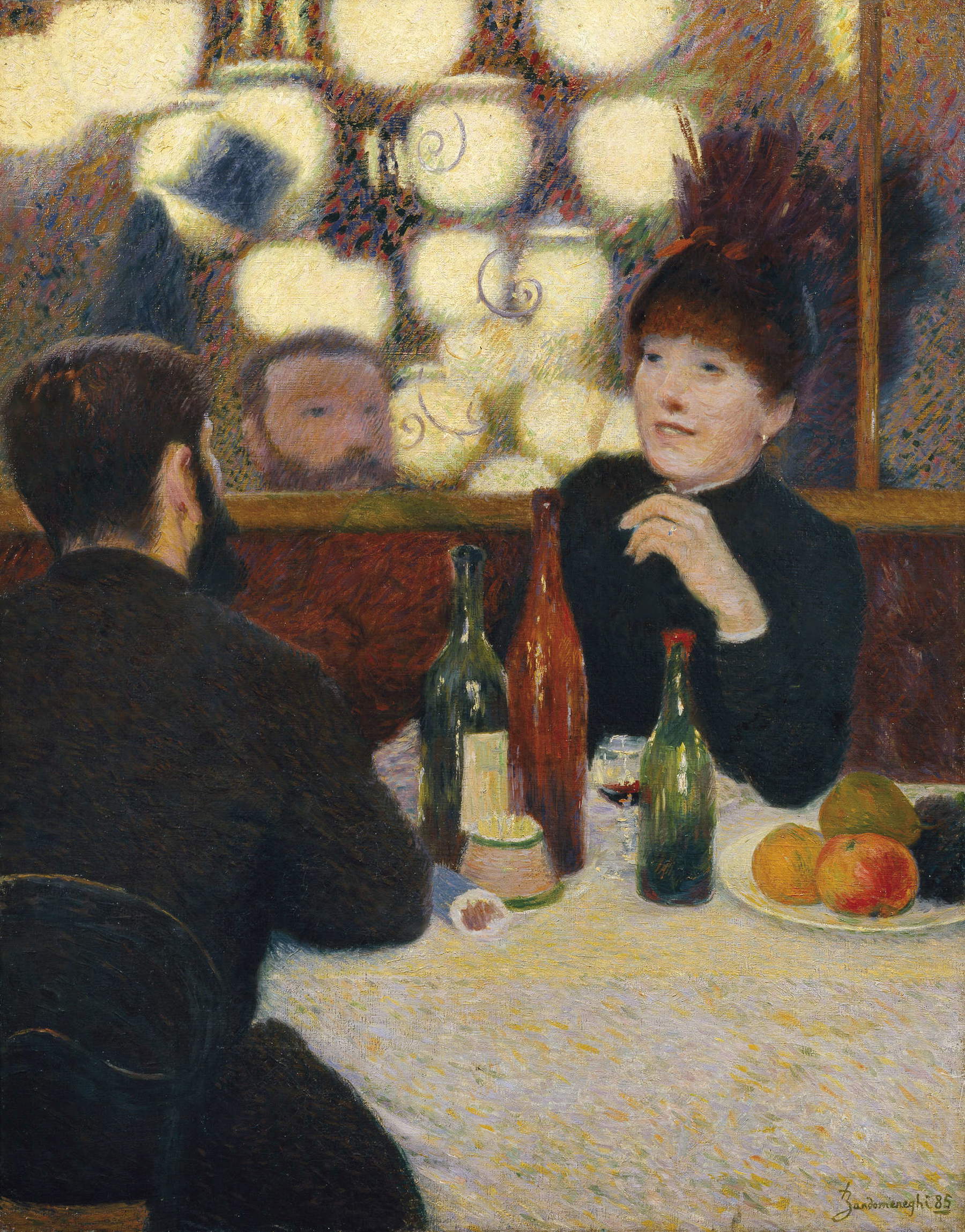

The dialogue of Italian painters with Impressionism, already mentioned in the subtitle of the Pisan exhibition, becomes even more evident in the section devoted to Federico Zandomeneghi and the Impressionists. The Venetian painter arrived in Paris the first week of June 1874, two to three weeks after the close of the first Impressionist exhibition, therefore. He was therefore affected by the great stir the event caused, but amid hesitations and a fluctuating attraction to this new painting, it was only from 1878 -1879 that his relationship with the Impressionists was affirmed and consolidated, thanks to Diego Martelli, the best-known patron of the Macchiaioli, who was present in Paris in those years. The critic had the opportunity to understand directly in the French capital the affinities between Impressionism and the painting of the Macchiaioli and, after having helped Zandomeneghi from a character point of view, since he was rather grumpy and grumpy, he succeeded in having two works of the painter’s Italian activity exhibited at the Impressionist exhibition of 1879, effectively bringing him into the movement. Out of all the Impressionists, Zandò felt closest to Degas (especially his pastels) and preferred to depict young middle-class maidens in particular, but with his own personal style, which mainly concerned coloristic choices close to his Venetian origins (note the mixing of colors in the backgrounds of the works exhibited). Prominent in this section, for the touches of color, the reflection of the round lamps on the mirror and the naturalness of the two characters, is the painting At the Café Nouvelle Athènes that the painter exhibited at the 1886 group show, but well noted here, through clear comparisons, is the artist’s affinity with certain Impressionist compositions: his Maiden with Yellow Flowers and Renoir’s Jeune fille au ruban bleu, his Bavardage and In the Garden of Mary Cassatt.

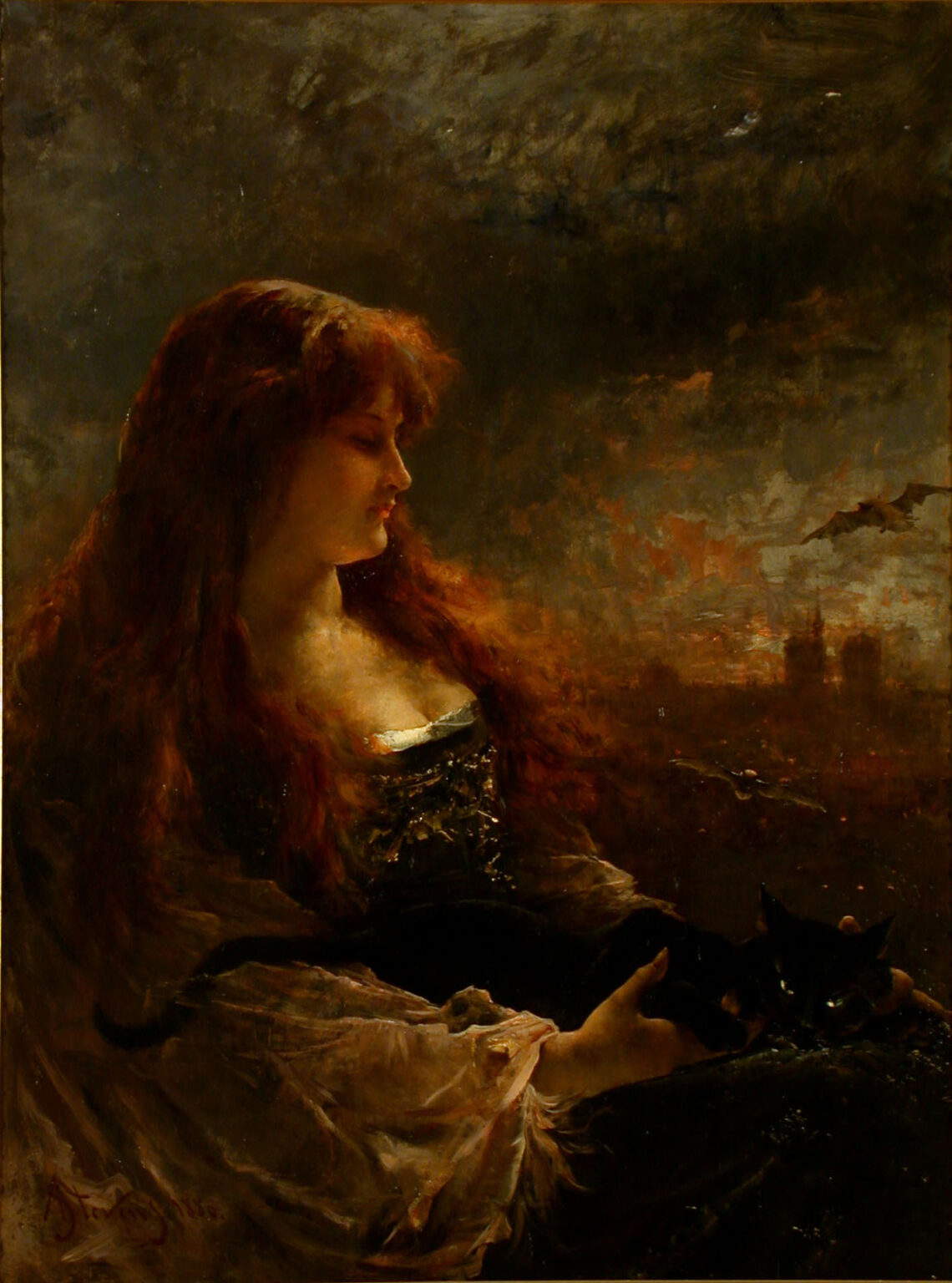

It is then with the choice to bring together in the next section, on the upper floor, the graceful Young Woman in deshabillé, Maiden with a black cat, Giovanni Boldini ’s Woman with bare breasts, and Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta ’s Le ruban rose that we wish to highlight the birth of a true cliché European cliché of elegance that found its center in the Parisian city and an obvious homologation of subjects inspired by life in the French metropolis by Italian and Spanish painters active in Paris in the late 1870s and 1880s: indeed, one notices a certain predilection for half-length depictions on united backgrounds of female figures, symbols of beauty and charm, characterized by mischievous smiles and lewd attitudes, which blur into the uninhibited (petticoats slipping, breasts being uncovered, bodies bending and transparencies). By contrast, another kind of fascination and mystery (evoked by the presence of bats and a black cat) envelops the woman in profile in the foreground with long, fluffy red hair down in Alfred Stevens’ L’Électricité, which brings to mind the seductive Pre-Raphaelite women and is instead meant to evoke the idea of progress. The exhibition is also an opportunity to restore Vicente Palmaroli ’s authorship of the Lady portrayed in his Parisian salon exhibited at the 1934 Venice Biennale with the apocryphal signature of Giovanni Boldini, a symptom of attributional turmoil in favor of the Ferrara master and to the detriment of Spanish painters of his contemporaries. The Leghorn-born Vittorio Matteo Corcos, another Italian fascinated by Paris, also embraced this European cliché of elegant modernity manifested in late 19th-century fashion, evidenced here by one of the painter’s masterpieces: the Istitutrici ai Campi Elisi, for him an expression of the universal idea of elegance and lightheartedness.

Still continuing in elegance is the penultimate section of the exhibition, but it is an elegance that is not set, but dynamic: not frontal and, so to speak, serious portraits, but more lively, more modern portraits, posed but not motionless and set in the everyday dimension. This was a new idea of portraiture for which Boldini was primarily the spokesman, but also his friends, such as Paul Helleu (whom Boldini portrayed in a work exhibited here while he was painting Madame Gautreau, Sargent’s famous Madame X ) and Jacques-Émile Blanche and John Singer Sargent himself. Prominent among these portraits is the one of little Subercaseaux, one of the sons of Chilean businessman and diplomat Ramon: dressed in an elegant marinet suit, the disheveled youngster, sitting on a small sofa with light and dark stripes, with one leg down and one leg up, seems to be slipping a little forward and a little to the side, and may not be sitting there much longer...

The exhibition that has taken us so far to Paris concludes... in Tuscany, with works by Luigi and Francesco Gioli, Michele Gordigiani, Angiolo Tommasi, Giorgio Kienerk, and that Vittorio Matteo Corcos of whom we had already had a glimpse, a little further back, with his beautiful Istitutrici. But why does this pictorial journey to the French capital among streets, boulevards, horse races, domestic interiors, fields and gardens end precisely in Tuscany? Because the Tuscan artistic society, through the frequent visits that various artists made to Paris, was influenced and updated more and more by following the figurative aspects in vogue in France. It was then mentioned how Diego Martelli had also sensed the points of contact between these two poles, and there is also to be considered how Boldini’s periodic returns to Tuscany helped to keep the Tuscan artistic milieu up to date with the changes in art taking place in the modern and elegant metropolis of Paris. Portraiture set both indoors and in front of urban and landscape views predominates, and here we are enchanted in front of Gordigiani’s evanescent Eleonora Duse, mesmerized in the direct gaze of the young woman in Corcos’s In Reading by the Sea, follow the sinuous lines of the backs of the three girls portrayed by Kienerk in Youth, and finally confront the enigmatic face of the girl sitting on the bench watching us with her legs crossed and her hand under her chin: where will she be with her mind the young woman depicted in Vittorio Corcos’ Dreams?

We leave the Palazzo Blu exhibition with this question. An exhibition that through its nine sections takes the visitor from one of the darkest moments for France to its happiest and most artistically and culturally active era . Which makes us understand how from defeat comes a bursting desire for rebirth, serenity, modernity, progress, and elegance that invests the entire bourgeoisie of the French capital and dictates the main trends in fashion and art in and outside the country. The frivolity and worldliness portrayed by the Italian painters of the Belle Époque is thus not superficiality or a betrayal of their homeland of origin, but the effect of the spirit of that era resulting from a desire for international redemption. And both the catalog that accompanies the exhibition project and the unraveling in the halls of the Pisan museum account for this. The exhibition design also turns out well (note the section panels that recall the thick, rounded signs still found in Paris today), and the international loans, including the Muséand d’Orsay in Paris, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Meadows Museum in Dallas (thanks to which it is possible to see Fortuny’s Spiaggia di Portici in Italy for the first time), and national, including a substantial body of works from the Pinacoteca De Nittis in Barletta. Most of the works on display are then from private collections, thus rarely seen by the public.

The exhibition at Palazzo Blu is thus a total immersion in the Parisian Belle Époque, made up of dialogues, comparisons, and human relationships among painters, through which a well historically framed era is told, bringing out a vibrant fresco, rich but never dispersive, that does not merely exhibit works, but invites an understanding of how a new idea of modernity took shape in Paris.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.