Writing about that splendid strip of land between the banks of the Upper Tiber, known as the Valtiberina, Antonio Paolucci argued, “In this part of Italy, Beauty is ubiquitous and pervasive. Ubiquitous because you encounter it everywhere, pervasive because it enters everywhere: in the civic museums guardians of celebrated masterpieces, in the historic villages and rural hamlets where the stones and bricks have the color of sun and bread [...].” There is no doubt that although by now Sansepolcro no longer has the scale of a village (in fact, it is now a town of just over 15,000 souls), this definition fully describes it. In the province of Arezzo, Sansepolcro is known for being the birthplace of Piero della Francesca, significant evidence of whom is still preserved there, but its charming historic center boasts numerous other masterpieces, including painting, sculpture and architecture.

There is no artistic itinerary or short visit to Sansepolcro that does not have the obligation to start from the Museo Civico, not only because it holds some of the most important masterpieces of the “monarch of painting,” the title by which the mathematician and intellectual Luca Pacioli called Piero della Francesca, but also because so many other treasures are found inside. This important museum finds its home in what was once the Palazzo dei Conservatori del Popolo in the center of the city. Here Piero della Francesca created the wall painting of the Resurrection, for some, including Paolucci, “the most beautiful resurrection in the History of Art.” Also located there is the Polyptych of Our Lady of Mercy, on which the Biturgese artist worked on several occasions between 1445 and 1462. The grandiose polyptych, though deprived of its original woodwork, is a work of rare beauty, dominated by the central panel with the Madonna opening her cloak to welcome the faithful and assuming the features of a “Bramantean niche,” as Roberto Longhi wrote of it. Completing the nucleus of works by Pierofrancesco are the two fragments of frescoes of St. Ludovico and St. Giuliano, which, although in precarious condition, still show that volumetric rendering and clarity typical of Piero.

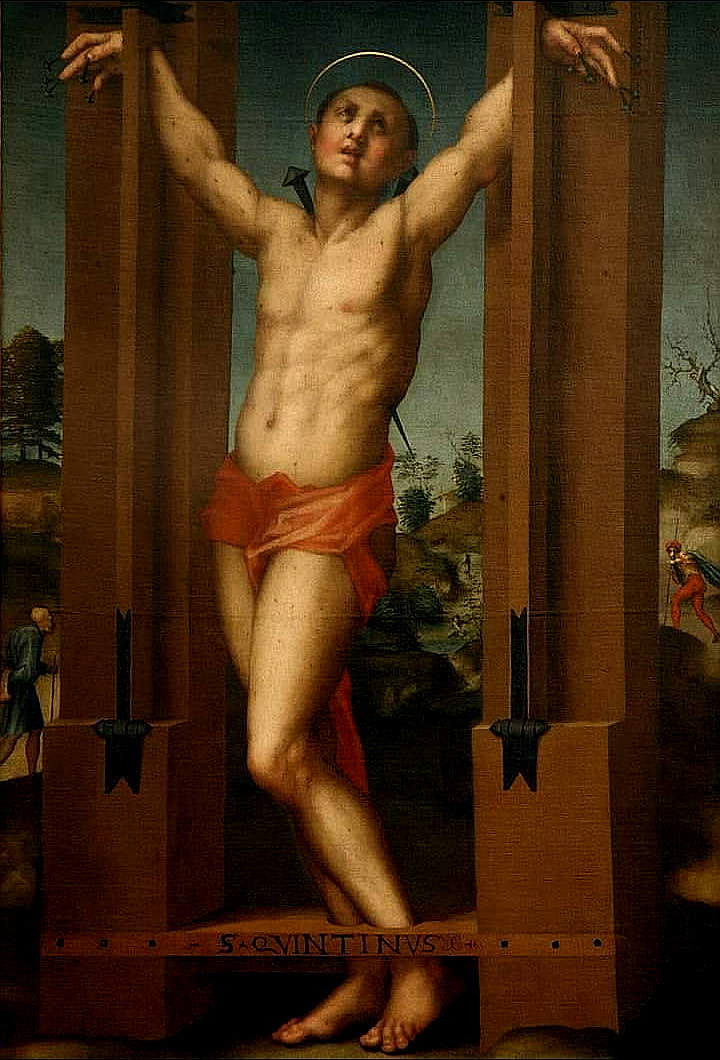

In addition to a selection of frescoes and sinopias from the city’s churches, the museum displays important works such as the panel of San Quintino, painted by Pontormo around 1517. The painting is also described by Vasari, who recalls how it was initially commissioned from Gianmaria Pichi, a pupil of the Empoli-born painter, but was eventually made by the master willing to help his disciple. The martyred saint is mindful in his slightly twisting pose of the classical sculptures of Praxiteles, studied by Pontormo, while the natural landscape behind him shows suggestions poised between the lesson of Fra Bartolomeo and that of Piero di Cosimo. Also of great quality is the complex glazed ceramic dossal with the Nativity by Andrea della Robbia, one of the highest examples of the Della Robbia spreads found in these lands. Other works by artists native to Sansepolcro, including Santi di Tito, Raffaellino del Colle, Matteo di Giovanni and Angelo Tricca, should be mentioned as being of no small interest.

Another artistic treasure trove is the Cathedral of Sansepolcro, with Roman-Gothic features to which it was restored by an arbitrary restoration perpetuated in the first half of the 20th century by erasing its Baroque elements.

The building began as an abbey in the complex of a Benedictine settlement that arose in the 10th century, perhaps to house the relics of the Holy Sepulcher, which according to ancient tradition were brought by two pilgrims from the Holy Land. The temple was enlarged when it became part of the Camaldolese congregation and then again in the 14th century, before rising to the role of bishopric in the 16th century.

Although in the course of time it was impoverished of some works, the most famous of which is Piero della Francesca’s Baptism of Christ , which was unhappily sold and after several changes of ownership came to the National Gallery in London, very important masterpieces of art history are still preserved there. The oldest is the Holy Face: a polychrome wooden statue of Christ Crucified, which shows remarkable affinities with the Holy Face of Lucca. The work, of uncertain date, for some it can be dated to the 8th-9th century while some lean toward the 11th century, and exhibits exceptional coloring (probably applied in the 12th century), both in the flesh of Christ and in the heavenly priestly robe. Like its counterpart preserved in Lucca, it is believed to be an acheropite icon, that is, not made by human hand but by divine intervention.

On the high altar, on the other hand, is arranged the sumptuous polyptych by the Sienese Niccolò di Segna in which the central panel depicts the Risen Christ, which was probably also a model for the work of Piero della Francesca. Instead, it was perhaps the artist from Biturg that suggested the motif of the curtain opened by angels, used in his Madonna del Parto (as reported in an article dedicated to it in this newspaper by Giannini and Baratta), to Andrea della Robbia, who took it up again in the delicate tabernacle kept here. Also by the della Robbia school are two ceramic sculptures of Saints Benedict and Romualdo on the counter façade.

Raphael del Colle also certainly could not have been unaware of comparing himself with Piero when he painted his Resurrection for the Cathedral, one of the earliest known works by the painter who was a pupil of Raphael, denoted, however, by a much more animated composition.

Other important works arranged in the aisles of the Cathedral are Perugino’sAscension of Christ , which repeats a model he had already made for the church of the Abbey of St. Peter in Perugia; thefresco with the Crucifixion by Bartolomeo della Gatta, rediscovered during the 20th-century rearrangement of the church; theIncredulity of St. Thomas painted by Santi di Tito; and theAssumption of the Virgin by Jacopo Palma the Younger.

A side door leads to the Cloister, with 16th-century frescoes, and the Chapel of the Monastery, where Piero della Francesca is said to have been buried.

If you still want to delve deeper into the history of Sansepolcro’s most illustrious painter, you can also visit his house, which stands in front of the garden dedicated to him, where the statue depicting him sculpted by Arnaldo Zocchi towers. The building, with its sober but fascinating architecture, formerly owned by the Franceschi family before Piero’s birth, was perhaps reorganized by the artist himself, as would be inferred from similarities with an architectural panel in his treatise, De prospectiva pingendi. In the house, now home to the center for studies on the artist and intellectual, there is a museum tour that allows visitors to discover his life and works.

But many other treasures of significant quality are preserved in the many sacred places scattered throughout the historic center of Sansepolcro, churches and oratories of great beauty not only for the works they preserve but also for their architecture.

The church of San Lorenzo holds one of the most important masterpieces of Mannerism. The facade of the temple is punctuated by an arched portico, just as the bulging body of Christ in Rosso Fiorentino ’s dossal is marked by the pronounced ribs of the rib cage. The work, known as the Deposition, is perhaps more correctly to be recognized as a Lamentation over the Dead Christ, since Jesus’ bruised body has already been laid down by the Cross. The cross in fact unlike Rosso’s other famous work in Volterra, parades in the background, leaving onlookers to gather around the body of the Messiah. The mournful drama that the Florentine painter infuses the scene with is the result of his tragic experiences with the Sack of Rome and an orientation toward Savonarola’s sermons. Vasari recalls that the work was originally commissioned from Raffaellino del Colle, who instead created the lunette above with God the Father blessing, but the latter decided to sacrifice his interests so that Sansepolcro would be enriched with a painting by the Florentine painter. The panel is currently in Florence where it has been restored by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, and will soon return to its original location.

In the beautiful church of San Francesco, with an exterior in 14th-century Gothic style but the interior renovated in the 18th century, there is an interesting canvas of the titular saint receiving the stigmata in a setting of lively naturalistic brio and a work by Passignano depicting the Dispute of Jesus among the Doctors. The church and adjoining convent were also frequented by the humanist Luca Pacioli.

The sober church of Santa Maria delle Grazie, denoted by a prestigious wooden ceiling, houses in a sumptuous tabernacle on the high altar the Madonna delle Grazie by Raffaellino del Colle painted for the confraternity to which the painter belonged. The oratory is decorated with a cycle of frescoes painted around the second half of the 16th century with stories from the life of the Virgin.

A few steps from Piero della Francesca’s house, on the other hand, is the church of San Rocco, where the large altar is a majestic work of carving by the Binoni brothers, from the first half of the 17th century, which houses a wooden statue of a 13th-century deposed Christ , probably originally part of a dispersed sculptural group. Facing the church is theoratory of the Company of the Crucifix, embellished with frescoes depicting Scenes from the Passion of Christ, executed by Alessandro, Cherubino and Giovanni Alberti, who belonged to a prolific dynasty of artists and intellectuals. A sandstone model of the Holy Sepulcher, taken from Leon Battista Alberti ’s design for Giovanni Rucellai’s tomb in San Pancrazio in Florence, can also be seen in a chapel.

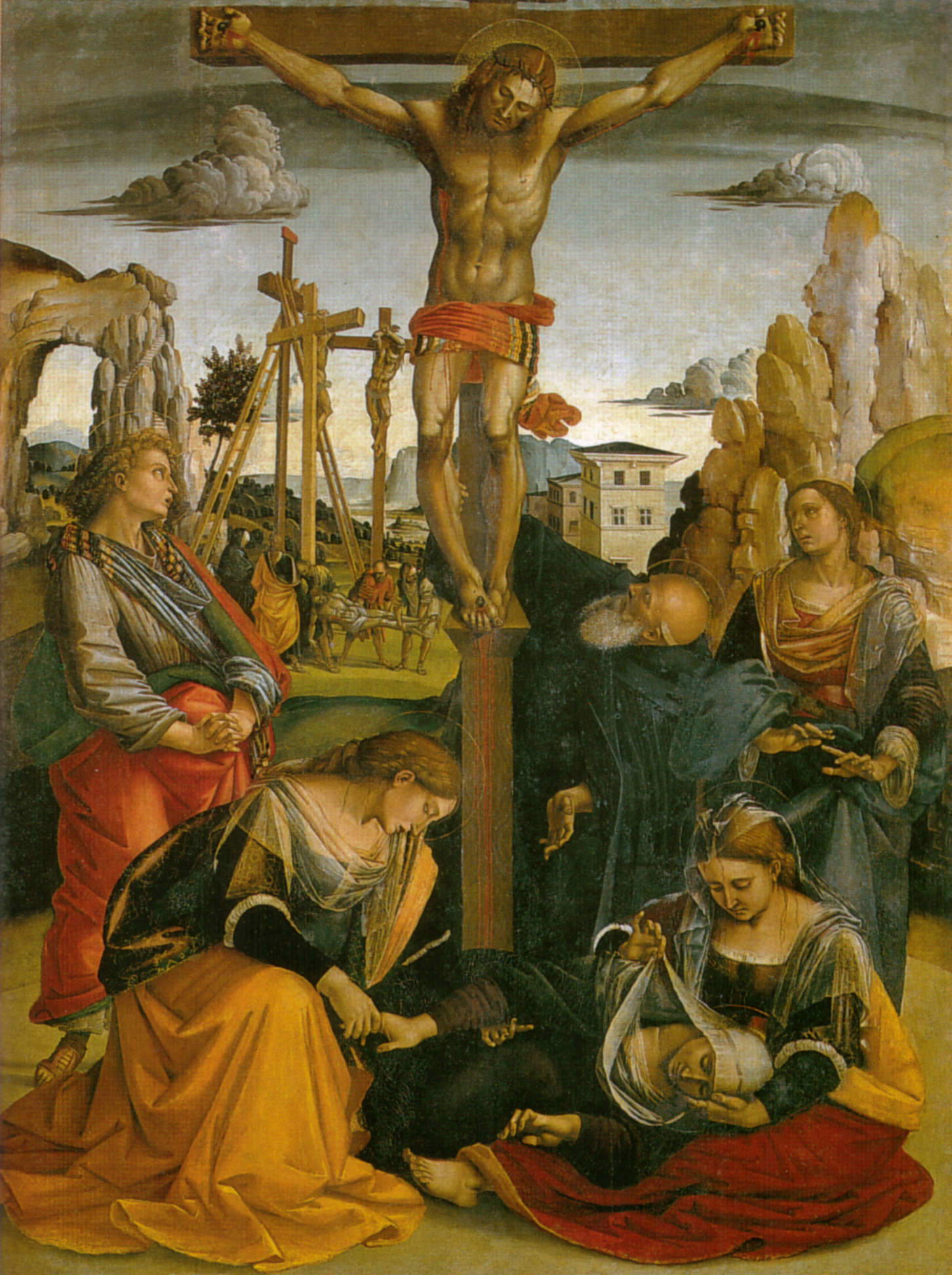

The ancient church of Sant’Antonio Abate, in whose façade is set a lunette with a 14th-century bas-relief depicting Christ Blessing between Saints Anthony and Eligius, preserves Luca Signorelli’s Stendardo della Crocifissione (Standard of the Crucifixion ) inside. It is painted on both sides, and is the late work of the Cortona-born artist: on the recto it bears the Crucifixion while on the verso St. Eligius and St. Anthony with the kneeling confreres. The first depiction is characterized by vibrant color rendering and a crowded but harmonious composition, and although the figure of Christ has some weaknesses of proportion, the scene is offset by the lively naturalistic setting that connotes the background of the sacred event. On the other hand, the other side shows the two monumental saints, characterized by their attributes and plastic bodies, while still in an archaic conception, the genuflected patrons of small features are arranged with hierarchical perspective.

Visitors still not satisfied can also push on to the church of St. John the Baptist, among the oldest in the historic center, where Piero’s Baptism of Christ once stood, now home to the “Bernardini - Fatti” Museum of Stained Glass. Here, 23 stained-glass windows of different sizes are on display, by artists active between the 19th and 20th centuries, and marked by the most diverse tastes: from the sober Neo-Renaissance, through the bizarre electric lines of Art Nouveau, to chromatic accents and freer forms.

The church of Santa Maria dei Servi also constitutes a stop of definite interest for the art lover, thanks to its remarkable paintings; in fact, there is a Mannerist work there by Cristoforo Roncalli known as the Pomarancio and Giovanni Ventura Borghesi, who was educated under Pietro da Cortona, master of the Baroque. Also on view are the surviving elements of an altarpiece with theAssumption of the Virgin and four saints by Matteo di Giovanni, executed in the late 15th century. In particular, the central panel, although damaged by a heavy fall of color, shows a fair rhythm between the opposing groups occupying the different registers of the work.

Slightly further from the center is the church of St. Michael the Archangel, built in the 17th century along with the Capuchin convent. An unexpected work is preserved inside, the dossal with Paradise painted by the mannerist painter, Capuchin friar Paolo Piazza, connoted by a brilliant palette and a moving composition overflowing with characters. Note, the very modern urban view, compressed at the lower end of the canvas.

Obviously, still numerous are the sacred places that the enterprising traveler will be able to discover in the city, as well as in the surroundings, such as the hermitageof Montecasale, and no less interesting are also the secular buildings, including towers and stately palaces. And certainly this article does not pretend to exhaust the subject, which is still surprisingly vast, testifying to how Sansepolcro can boast a cultural heritage of the highest order.

|

| What to see in Sansepolcro: a historical-artistic itinerary through the streets of the center |

The author of this article: Jacopo Suggi

Nato a Livorno nel 1989, dopo gli studi in storia dell'arte prima a Pisa e poi a Bologna ho avuto svariate esperienze in musei e mostre, dall'arte contemporanea alle grandi tele di Fattori, passando per le stampe giapponesi e toccando fossili e minerali, cercando sempre la maniera migliore di comunicare il nostro straordinario patrimonio. Cresciuto giornalisticamente dentro Finestre sull'Arte, nel 2025 ha vinto il Premio Margutta54 come miglior giornalista d'arte under 40 in Italia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.