Perfume is an enveloping, intoxicating, fragrant, full, hypnotic work. A disruptive cascade of adjectives could go on to overwhelm Luigi Russolo’s masterpiece, a painting that can be seen and smelled, heard and admired, which aims to evoke in the viewer sensory experiences capable of involving not only sight but also smell. Of the Futurists, Russolo was among the most stubborn and constant in the search for a multisensory art, a synesthesia between forms, colors, sounds, and scents. Russolo is remembered for being the most innovative experimenter in musical futurism: it was April 21, 1914, when the Venetian artist presented his Spirali di rumori in Milan, a concert written for his “intonarumori,” curious musical instruments that he himself invented. They were sound generators consisting of a wooden case and a cardboard or metal loudspeaker, created with the aim of evoking the sounds of a city in motion, of a battle, of a racing automobile: rumbles, thunders, buzzes, gurgles, bursts, hisses, howls, voices, laughter, crackles, rustles. To each of the intonarumors, a different sound, and a name derived accordingly: rumblers, buzzers, and so on. “Our ear demands ever broader acoustic emotions,” Russolo had written in his manifesto The Art of Noises. Symphonies of noises to express “the rotating noise of the African sun and the orange weight of the sky,” Marinetti would have said, to create “sensations of weight, heat, color, smell, and noise.” These are the foundations on which Russolo based his multi-sensory poetics.

And he had anticipated them in 1910, when, as a 25-year-old, he painted his Profumo, shortly after meeting for the first time Umberto Boccioni, who was 27 years old, in December the year before. Two painters fascinated by Marinetti’s manifesto, two young men who bonded in a deep friendship, two avant-gardists who intended to subvert Italian art by shaking its foundations. “We introduced ourselves to each other,” Russolo recalls in a manuscript preserved in the archives of the Mart in Rovereto, the museum that now preserves his Profumo. “Our ideas found themselves kindred, our artistic ideals very close, an equal hatred for the already done, the refried, the commonplaces in art put us immediately in intimate contact. We became friends.” It was precisely in 1910 that they met Marinetti and, together with him, Balla, Carrà and Severini, published the Manifesto of the Futurist Painters on February 11. And from that text deflagrates another explosion of devastating and devastating, violent and resounding energy, adding to that with which, the year before, Marinetti had caused great turmoil in an artistic environment that was preparing to welcome new, tumultuous, radical transformations.

“For other peoples, Italy is still a land of the dead, an immense Pompeii whitewashed with sepulchres.” “We declare war, resolutely, on all those artists and institutions that, while disguised in a garb of false modernity, remain entangled in tradition, in academicism, and above all in a repugnant cerebral laziness.” “We denounce to the contempt of youth all that reckless scoundrelry which in Rome applauds a stomacheble revival of softened classicism, which in Florence exalts neurotic devotees of’a hermaphroditic archaism, which in Milan enumerates a pedestrian and blind Forty-Eight manual dexterity, which in Turin inhales a painting of retired government officials, and in Venice glorifies a farrago patina of fossilized alchemists.” Every sentence is a tirade against academies and their teachers, against museums, against devotees of the classical, against official art. The new painting must magnify modern life, the magnificence of the future. “It is vital only that art which finds its own elements in its surroundings.”

|

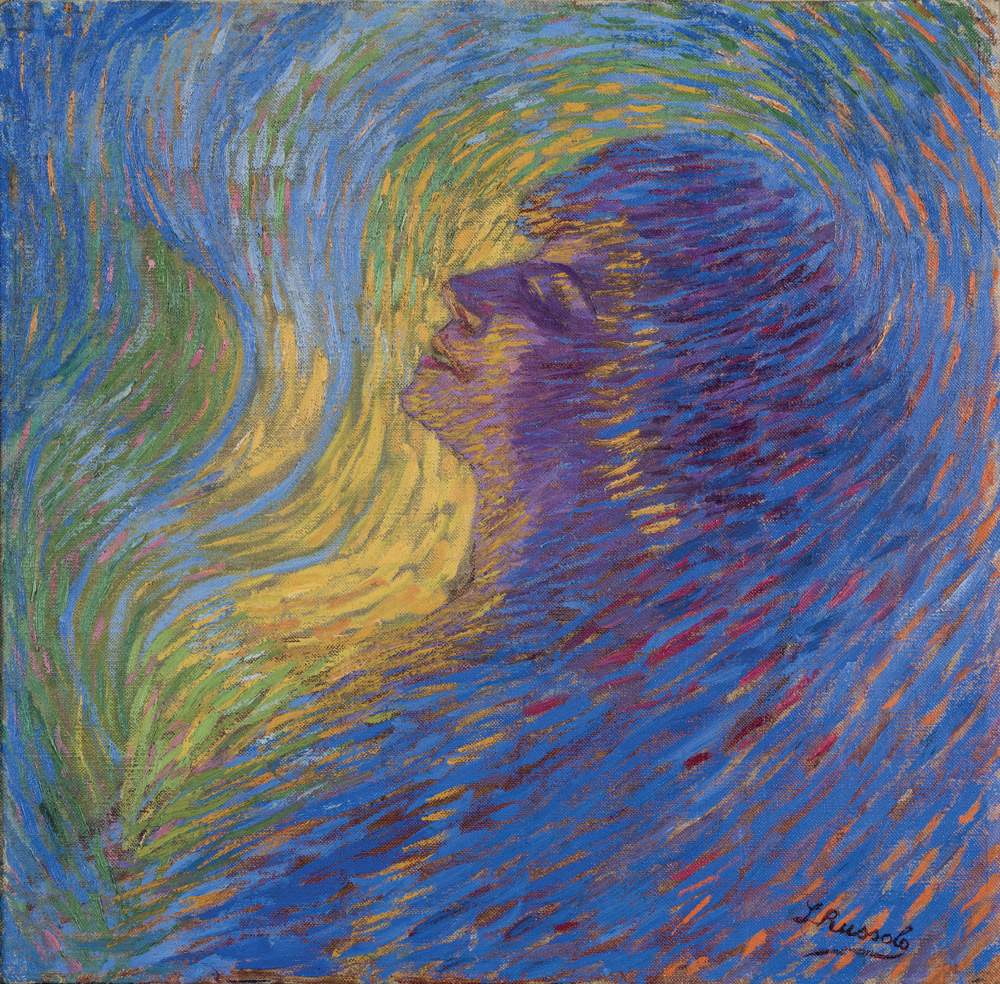

| Luigi Russolo, Perfume (1910; oil on canvas, 65.5 X 67.5 cm; Rovereto, Mart, Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Trento and Rovereto, VAF-Stiftung Collection) |

|

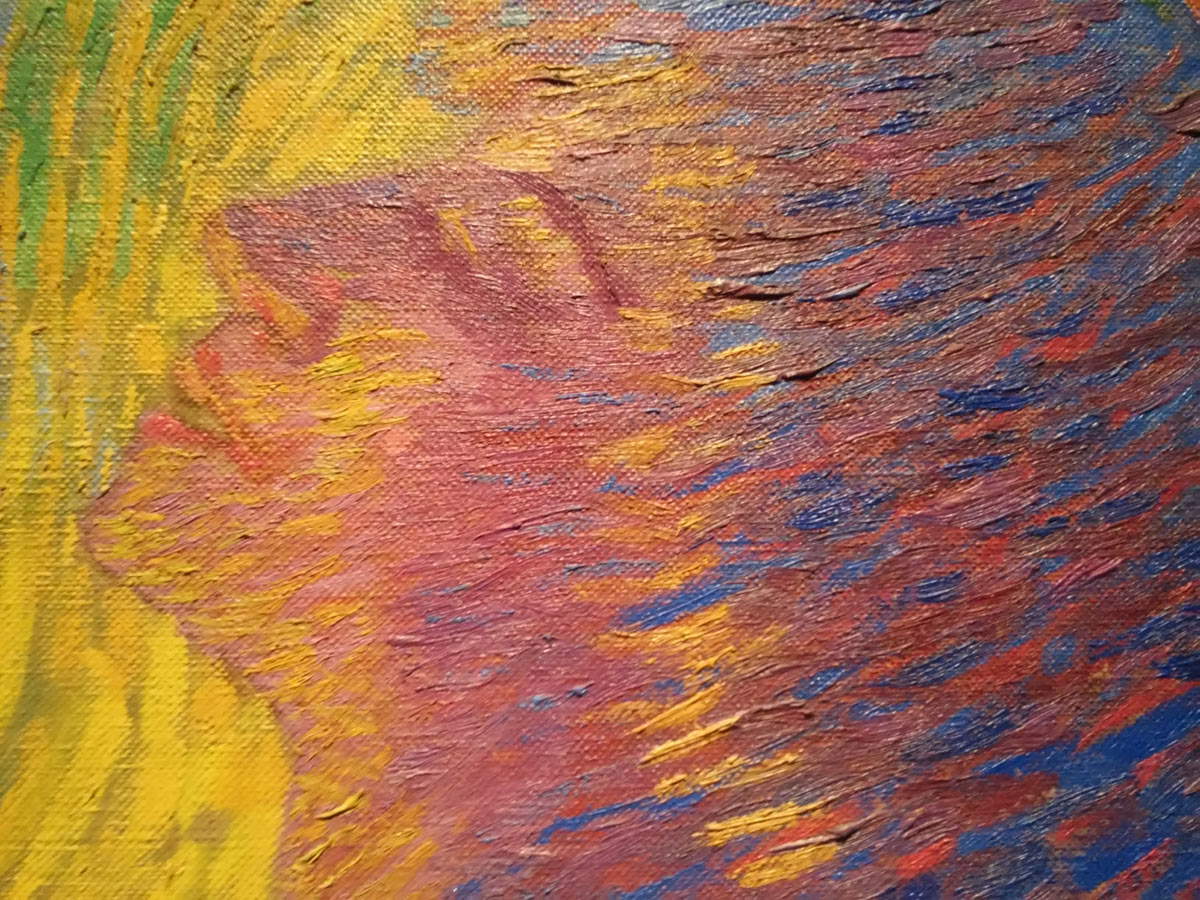

| Luigi Russolo, detail |

|

| Luigi Russolo, detail |

Luigi Russolo’s Perfume is one of the first concrete evidences of the Futurist painting manifesto. A woman, beautiful, with features at once sharp and delicate, is caught in profile, as she reclines her head slightly backward, her eyes closed and her mouth half-open, as if enraptured by the fragrance wafting through the air: the perfume takes on the appearance of a swirl of color that envelops her slender, elegant profile, and frays as it follows waves, rivulets, halos that diminish in chromatic intensity as they recede from the woman’s face. A golden wave laps her neck and chin as it rises to her nose, caressing her with essences we imagine fresh, sparkling, citrusy. Further away from her, sky-blue and violet tones dominate, punctuated here and there with touches of pink and orange: colors that do not pertain to the world of nature, but evoke the aromas that waft through the room with spicy effluvia. Like a perfume that first arrives with top notes, the most intense but the first to evaporate, then spreads with softer but more full-bodied heart notes and finally lingers with persistent base notes, so is Russolo’s painting: a stormy whirlwind when he is close to the woman, and calming and finding a more defined personality as he becomes more distant. A whirlwind that Russolo arranges on the canvas with a dense, stringy brushstroke, heir to Previati’s, which constitutes its most direct precedent, since Profumo is still a painting well rooted in the Divisionist experience: a brushstroke that is textural, that allows a glimpse of the grain of the canvas, which in the golden detonation that penetrates the young woman’s nostrils becomes thicker and heavier. An odorous cloud that evokes Huysmans’ Des Esseintes who, in the tenth chapter of À rebours, floods the room with perfumes to intoxicate himself: “hastily diffused exotic scents, emptied the vaporizers, lavished his concentrated spirits, left the bridle to all his balms and, in theexasperated sultriness of the room, exploded a demented, sublimated nature that took one’s breath away, that charged with delirious alcoholics on an artificial breeze, an unreal and fascinating nature, all paradoxical, that brought together the pimentos of the topicals, the peppery whiffs of the sandalwood of China and theediosmia of Jamaica to the French odors of jasmine, hawthorn and verbena, which made trees of different essences, flowers of the most opposite colors and fragrances appear in spite of the seasons and climates, which created with the fusion and with the collision of all these tones a general perfume, nameless, unforeseen, strange.”

Scholar Maria Elena Versari has traced a sort of formal archetype of Perfume in Gaetano Previati’s Marys at the Foot of the Cross , and others have related the Portogruaro painter’s work to a Portrait of a Futurist by Boccioni, also painted in 1910, as a response to a Marinetti text, Uccidiamo il chiaro di luna: Maurizio Calvesi had pointed out that both paintings, Boccioni’s and Russolo’s, would seem to have been inspired by that 1909 text, which speaks of “vaporous locks of countless swimmers sighingly opening the petals of their moist mouths and eyes”, and of an “intoxicating deluge of scents” where “we saw a fabulous forest growing expansively around us, whose arching foliage seemed to be blown out by a too-slow breeze.” Russolo, however, manages to be even more impetuous than Boccioni: in an article published in La Nazione on May 25, 1911, critic Carlo Cohen wrote that Profumo “gives precisely the sense of voluptuousness and abandonment.”

Fourteen years later, Fedele Azari penned the manifesto La flora futurista ed equivalenti plastici di odori artificiali. And those “suave scents of flowers” that for Azari were “insufficient to our nares,” already with Russolo found their own synthetic dimension, which materialized in his synaesthetic painting.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.