by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 10/11/2018

Categories:

Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

Andrea Chiesi, one of the most interesting contemporary painters, transfigures reality in his suburban views and contemporary ruins, between Caspar David Friedrich and CCCP.

The studio of Andrea Chiesi (Modena, 1966) is in a farmhouse on the outskirts of Modena, just after leaving the city, on the edge of a countryside that loses itself between the Secchia on one side and the provincial road that leads to Carpi on the other: a place as if suspended, between the continuous clanking of the ring road not far away and the rustle of the wind that stirs the elms along the river and that, little by little, replaces the din of the road as one enters the fields. Already the very act of arriving at Andrea Chiesi’s studio is a kind of journey within a journey, dense with lyricism, especially when made on the threshold of autumn and in the early evening, when the first chill shakes the air and a slight mist descends to make the moonlight even more flickering. Behind it, there seems almost to be the direction of a Giovanni Lindo Ferretti sounding a dirge of his own: “the city vanishes, the traffic fades, poetry imposes itself, the moon rises, takes off.” The frescoes that begin to make their way into our imagination then end up materializing as soon as we cross the studio door: On the entrance wall hangs a 2016 painting, number 32 in the Karma series (Chiesi has always been used to working by series), which depicts, with the sparse palette typical of the Emilian artist (in most of his paintings it is difficult to count more than four or five colors), a corridor of an abandoned building, and on the tiles that cover the lower portion of the wall we catch a glimpse of what is perhaps Ferretti’s most famous couplet: “io sto bene / io sto male.” The condition of a generation enclosed in two verses, the reversal of the image of a decade in a synthesis of only six words, the existential substratum of a culture that those of my generation could only know by reading a few books, listening to records or at most the stories of those who were there: this is the basis from which Andrea Chiesi’s art was born and developed.

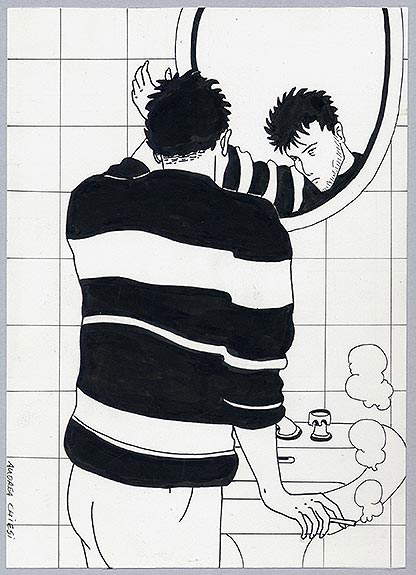

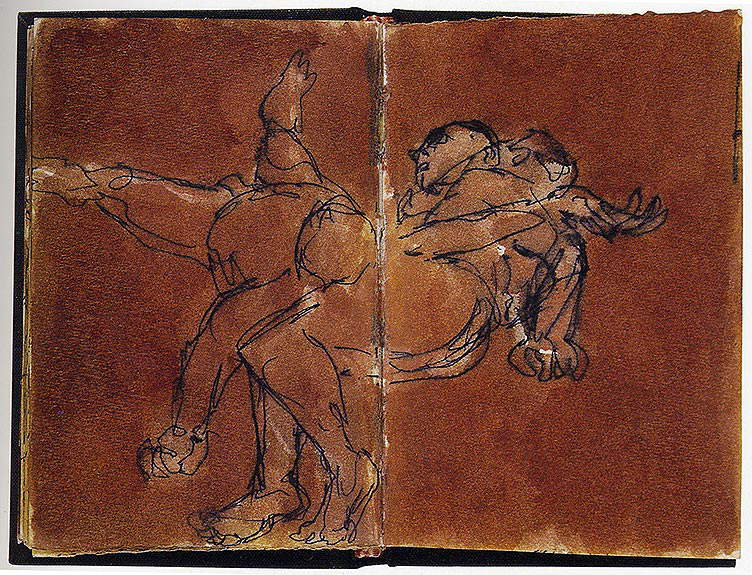

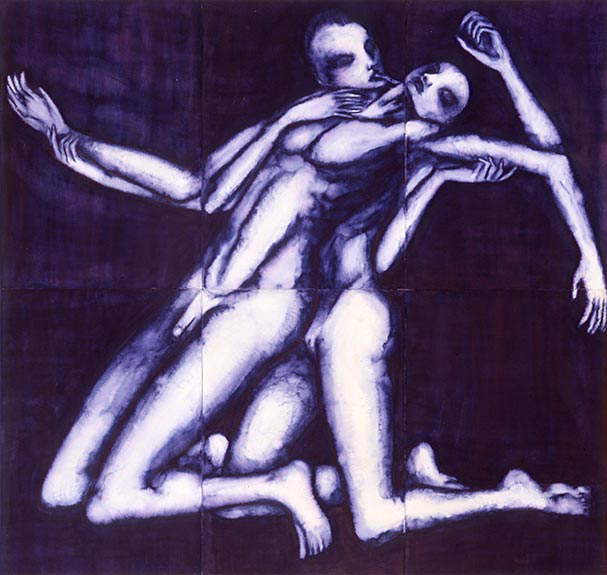

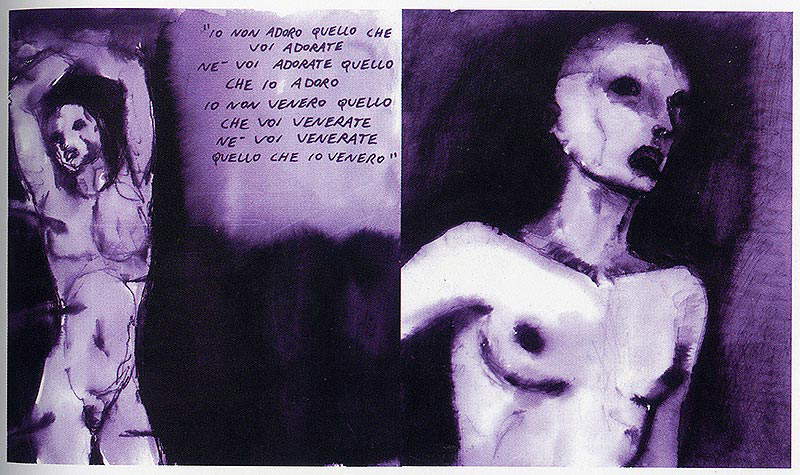

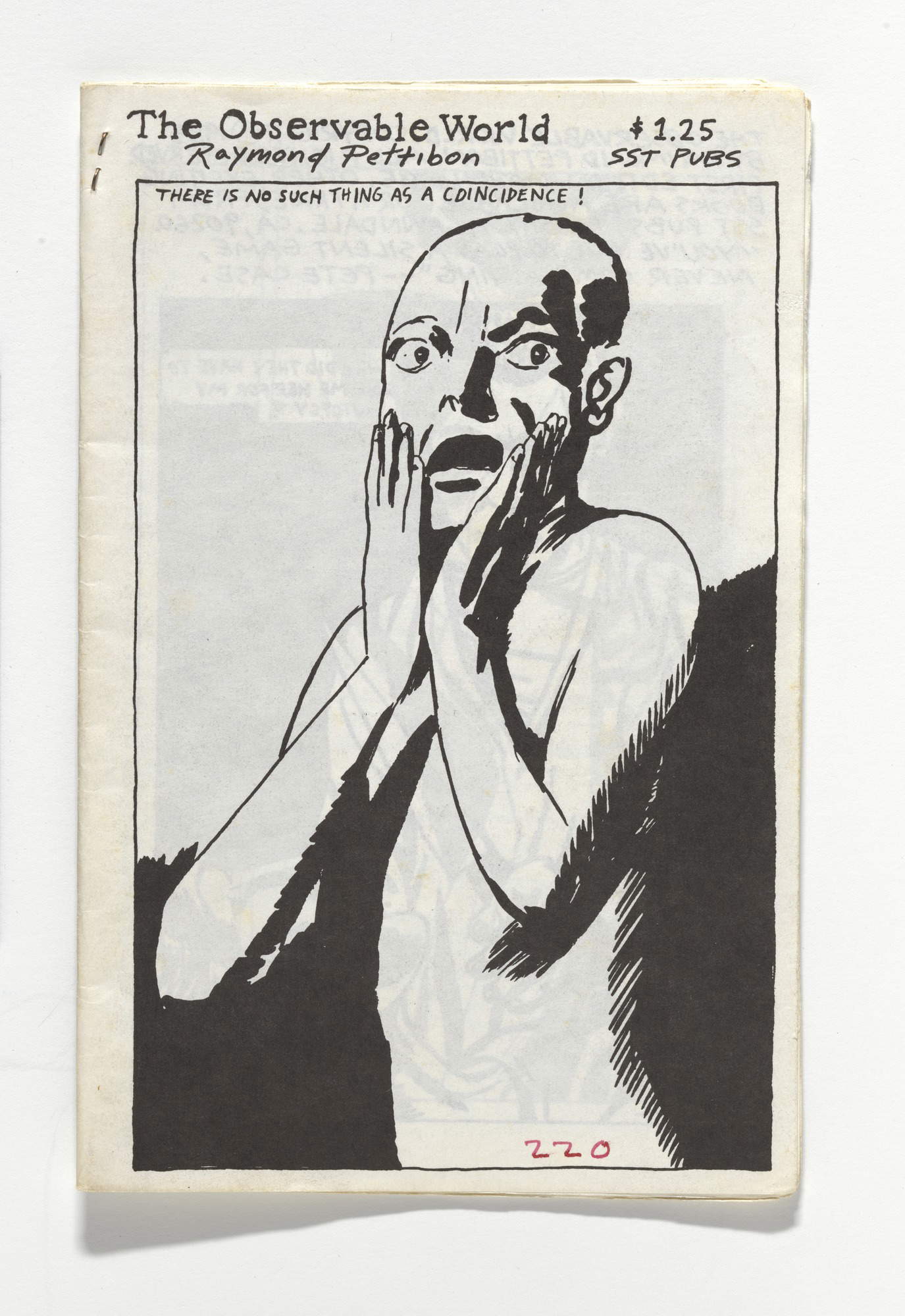

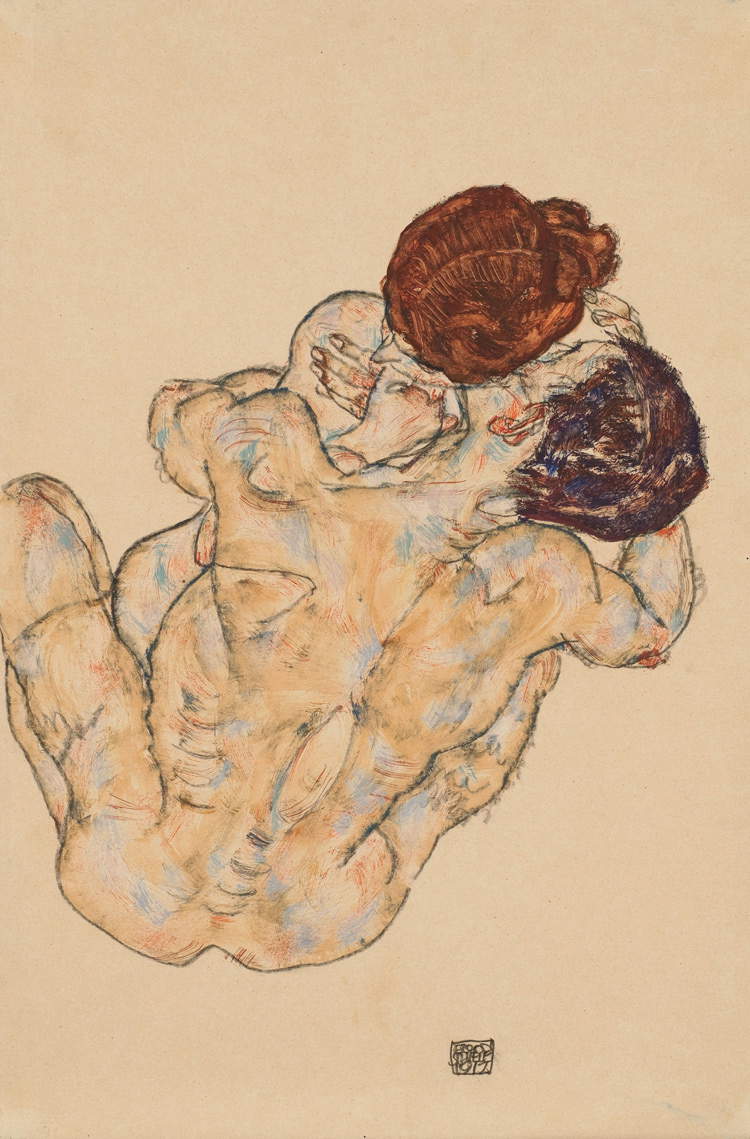

In all his biographies we read that he was self-taught, frequenting the punk scene and the social centers of the paranoid Emilia of the 1980s (it is impossible not to mention the Tuwat in Carpi), working in close contact with independent musicians, and making his debut as a draftsman and illustrator, telling on paper, with fluid but animated, strong and almost brutal signs, the feelings, myths and anxieties of that counterculture. The beginnings of his artistic career are filled with black-and-white figures à la Raymond Pettibon, which, however, as was typical of many Italian punk artists, are often cloaked in strongly expressionist accents that look to the German avant-garde, but also to earlier periods (some of his figures from the early stages of his career bring to mind the bodies of Schiele): it is no mystery that the Emilia of the 1980s was fascinated by the aesthetics of Eastern Europe. Thus, soon, those figures traced by sharp contours begin to lose their individuality, almost begin to float in the void, take on an unnatural purplish hue, are pervaded by a palpable eroticism even where it is not made explicit, and continue to populate Chiesi’s art even years later, albeit within a more intimate and private dimension, on notebooks. They are figures that fall, get up, pair up, sail over a gloomy void, sometimes they convey the impression that they are the result of long meditations, sometimes they seem almost drawn on the spur of the moment, here and there a text to accompany the image (unfailing quotes from CCCP), the composition is always happy, The composition is always happy, well balanced and organized according to solidly disciplined rules, the gaze seems more like that of a director than that of a painter, given Chiesi’s propensity to play with framing, experimenting with new cuts, capturing the subject with abrupt changes of perspective, zooms and tracking shots.

It would be all too easy to stress that this is a painting strongly imbued with humanity (as well as love) and that it questions the condition of our existence. In part perhaps this is true, but Andrea Chiesi’s painting is beyond complex and takes on multiple levels of interpretation, and this used to happen even in his early works. The very relationship between solids and voids transcends the mere technical element. Emptiness in Chiesi’s works, from his earliest achievements in the 1980s to his latest works, has a value, it refers to the unconscious, the esoteric, the mystical. But his painting is also inextricably linked to reality: in a text published in 2003, Sarah Cosulich Canarutto, speaking about some works of that period, wrote that Chiesi’s works are at the same time pervaded by a certain religious sense and yet anchored to reality, albeit through a process of distillation and sublimation. The summa of these early experiences was theApocalypse of John, a 1998 project that Chiesi put on in Reggio Emilia, in the company of the then CSI, an evolution of CCCP: in the cloisters of San Pietro, the artist arranged his sheets made for the occasion, and on the evening of the inauguration the CSI, led by the usual Ferretti (and on that occasion, however, without Massimo Zamboni) staged a sort of performance during which Ferretti declaimed verses moving from one room to another, in front of Chiesi’s works. And perhaps the meaning of those figures can be summed up in some of those verses: “wandering nomads, and the more we wander, the farther we are from the truth. So are we, wandering nomads, and we shepherd our flock of thoughts on the plateaus of the soul, taking them from the wolves of the night.” And again, “one must burn or stay away, consult the authorities, enlist in the fire brigade, stay away.”

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Karma 32 (2016; oil on linen, 50 x 70 cm) |

|

| Andrea Chiesi, one of the first drawings |

|

| Andrea Chiesi, one of the first drawings |

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Everything Remains in the Mind of God (1995; ink on paper, 36-page notebook, 16 x 11 cm) |

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Cure Me (1998; ink on paper, 200 x 210 cm) |

|

| Andrea Chiesi, The Apocalypse of John III (1998; ink on paper, 36-page notebook, 24 x 21 cm) |

|

| Raymond Pettibon, The Observable World (1985; lithographic print artist’s book, 21.6 x 14 cm; New York, MoMA) |

|

| Egon Schiele, Mann und Frau (Umarmung) (1917; gouache and black pencil on paper, 48.9 x 28.9 cm; Private collection) |

After that experience, Andrea Chiesi’s painting took other paths, but the desire to continue to use the painting as a means of representation of the self and of the sublimated real, and the desire to continue the search for a kind of contemporary Gesamtkunstwerk, sincere, urban, still punk-tinged (because after all, punk, although now swallowed up by fashion and marketing, is first and foremost a way of life), never failed. Only that the Apocalypse no longer takes the form of human beings floating in the void, but manifests itself in the abandoned architecture, in the lonely places, in the ruined buildings delineated with the cleanest clarity, with the perspective rigor of a Renaissance master, after a careful work performed from the photographic medium and leading to the transfiguration of the objective datum: human presence is set aside (and survives, if anything, in the notebooks), because those desolate places already speak for themselves, with no need for figures to add anything, to transform the picture into a narrative. This is not the goal. If anything, some narrative (assuming one necessarily wants to find it, assuming it is so necessary to want to discern a plot rather than a meaning in Chiesi’s painting) is rather contained within the ruins. Man was present in these landscapes, and his absence now heightens the sense of ruin of these places. The attitude is that of the Romantic painter who visits ruins (and Chiesi has always done so: since the 1980s his sources of inspiration have been abandoned factories, rundown suburbs, disused industrial buildings, and dilapidated gas stations, even before so-called urban exploration became a kind of empty and frivolous fashion) and who, in this attraction to ruins, becomes an accomplice of nature, as Georg Simmel had written, because his mode of operation becomes opposed to that which characterizes the very essence of man.

However, the tragic, moving component is missing, and the political one takes over (obviously in the highest sense of the term), since many of the places Chiesi chooses to transfigure with his painting are places charged with a social experience that, in a certain way and under certain forms, is still strong and pulsating. Look at the works in the Kali Yuga series, for example: they depict glimpses of the former steel mills of Cornigliano, a western suburb of Genoa. Disused industrial structures where workers’ lives have passed, frenetic centers of production, places of struggle and claims. Chiesi’s painting, however, is not mere documentation; his is not a photographic work. Painting cages time, slows its course (even in the concreteness of daily practice: when I visited his studio, and saw a work still in progress, Andrea explained to me that it can take up to several months before he completes a single painting), it allows the identity of the place to emerge (the former Cornigliano steel mill is not just any steel mill, but it is thatsteel mill, with its history, its vicissitudes, the pasts of the individuals who worked there), and often the abandoned places are as if pervaded by a metaphysical light that offers a new possibility of life. In essence: not documents, but visions. The title Kali Yuga itself, after all, contains in itself the germ of expectation, of rebirth: the artist has repeatedly explained that Kali Yuga, the age of Kali, in the Hindu religion is the current era, “a dark and gloomy era,” to use Andrea Chiesi’s own words, "characterized by numerous conflicts and widespread spiritual ignorance. There is a development of material technology set against a huge spiritual regression and a general spread of false gods, idols and masters. Kali Yuga is the last of the four Yugas and ends with the end of the world as we know it. It will be followed by a new Satya Yuga, or Golden Age, and the return of Earth to an earthly paradise." Abandonment translates into poetry and, through those somber hues on the dark blue, invites introspection and meditation: blue, Kandinsky argued, is the color of deep meanings, and its propensity for depth is all the more vivid the more intense its hue.

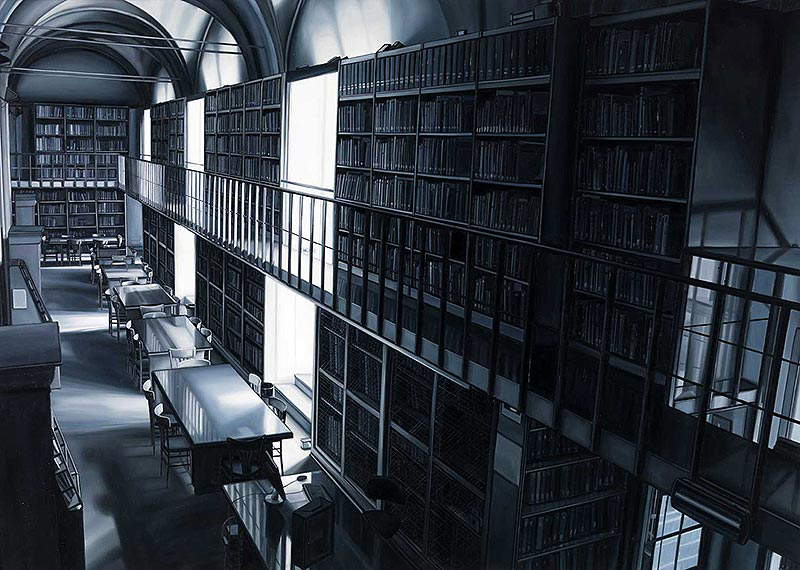

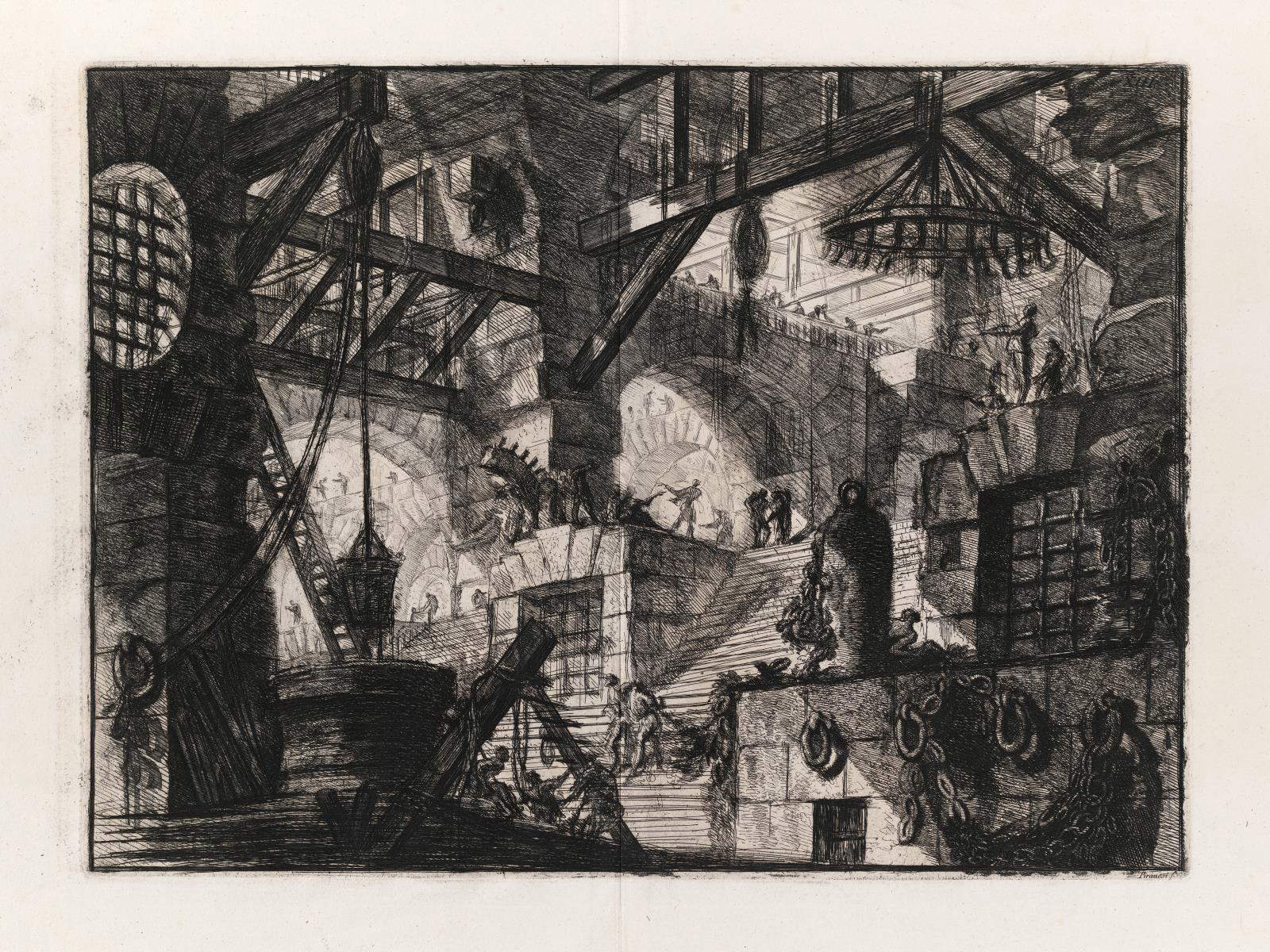

But Andrea Chiesi’s imposing architectural structures also glow with dense and sometimes unexpected symbolic meanings. There is a sense of precariousness when one wonders what the end to which the objects Chiesi depicts in his paintings will be destined. There is a certain degree of melancholy, if it is true that melancholy is that “signpost of an erased geography” of which Luigi Ghirri, a photographer also from Emilia and equally fascinated by desolate landscapes, spoke. There is the same relationship of man with the ruins, which take on epic contours, as it was in Anselm Kiefer, whom Chiesi cites among his cultural references (“in Kiefer,” the artist pointed out in an interview with Simone Menegoi, “the theme of solemnity returns, of epicness, which I feel when I paint what was a gas station and which becomes a suspended monolith, a dark deity, linked to our technological time, but also - perhaps because it is black - to something archaic, tribal”). There is the complexity of the present, to which the dense geometric textures of a steel tower, a colonnade, the skeleton of a shed refer, and whose formal perfection bordering on abstraction (and on which Andrea Chiesi’s lenticular attention is focused) becomes a metaphor for the many textures that animate the world, as well as our minds: certain of his works almost bring us back to Piranesi’s Carceri d’invenzione, although there is only a glimmer of that sense of helplessness that transpired in the Venetian’s reveries, and although in Andrea Chiesi the possibility of an order is configured (or at least this is the perception). There is the reflection on memory, which is then a constant in the Modenese painter’s art, and it is not uncommon for it to take on the guise of the many views of interiors of libraries or archives that in his exhibitions (as well as in his studio) alternate with urban landscapes: memory, which in archives and libraries accumulates and settles, is the means that blocks total desolation, restores life to things and nails the observer to the present forcing him to think about the future. “Sieh zu wie die Zeit zerfällt vor unseren Augen,” screamed Blixa Bargeld’s voice in a piece by Einstürzende Neubauten (which incidentally, translated literally, means “new buildings collapsing”). “See how time is crumbling before our eyes”: also in Andrea Chiesi’s works there is this sort of invitation to look at the ruins, the emotional tension that transpires from his works is absolute and tangible, and the contemplative dimension is sought and wanted since it is inherent in the pictorial medium itself. But contemplation has positive connotations, emphasized by many of those who have dealt with Andrea Chiesi’s art. Because it imposes reflection, forces questions, spurs the viewer to imagine a future beyond the ruins.

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Sidereal 26 (2000; oil on canvas, 100 x 150 cm) |

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Time 52 (2005; oil on linen, 100 x 140 cm) |

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Kali Yuga 13 (2006; oil on linen, 25 x 35 cm) |

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Kali Yuga 29 (2006; oil on canvas, 100 x 70 cm) |

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Ombra 13 (2009; oil on linen, 100 x 140 cm) |

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Perpetuum 17 (2011; oil on linen, 35 x 50 cm) |

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Uchronies 26 (2013; oil on linen, 35 x 50 cm) |

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Eschatos 9 (2018; oil on linen, 100 x 140 cm) |

|

| Anselm Kiefer, Interior (Innerraum) (1981; oil, acrylic, and paper on canvas, 287.5 x 311 cm; Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum) |

|

| Giovanni Battista Piranesi, The Well, from the series Carceri d’invenzione, second edition, plate XIII (1761; etching, 56.5 x 80.3 cm; Boston, Museum of Fine Arts) |

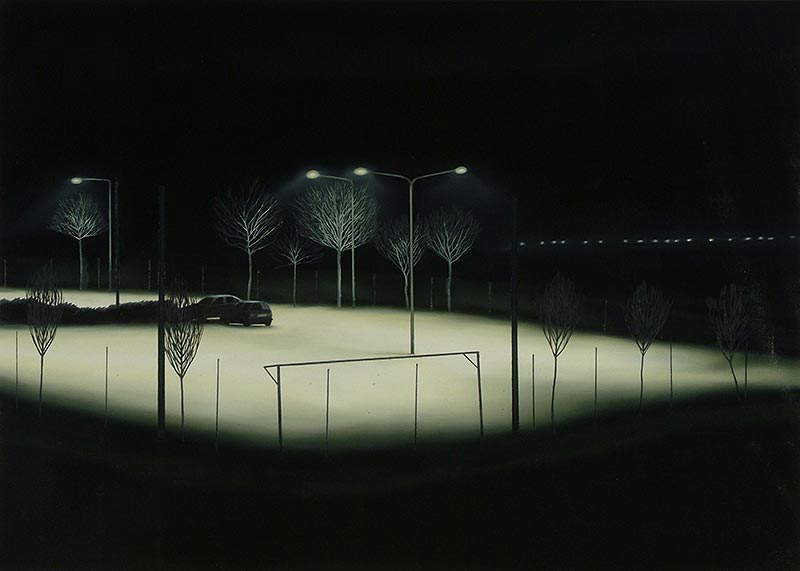

In more recent works, nature has returned to take possession of architecture: that complicity of which Simmel wrote still takes place in some of Andrea Chiesi’s newer works. It is not that there had been a lack of natural landscapes before, or landscapes where human traces (albeit banal and everyday) and the scenery of nature were in balanced coexistence: in 2003, those familiar Modenese countryside, so seemingly banal but in reality so deeply linked to a sense of the passage of time that the artist wants to capture on canvas, were the protagonists of a cycle, The House, created from a video that Chiesi had shot in the summer of that year just outside his home (hence the title of the series). The result was paintings that were also dense with a poignant poetry that elevates the everyday, synthesizes time, and weaves a dense web of simple emotions that are still capable of transfiguring reality, even if only in a memory, in an experience: a parking lot among fields illuminated by the dazzling light of a streetlamp, Turner-esque cloud plays that thicken over high-tension pylons or engulf a blurred horizon, lightning that rips through a seemingly quiet night, a grove that acts as a somber backdrop to a playground shrouded in the glow of electric lights. The natural component, it was said, has here and there punctuated Andrea Chiesi’s production: now, however, he appropriates it in ways that return with renewed vigor, or that are proposed tout court as novel.

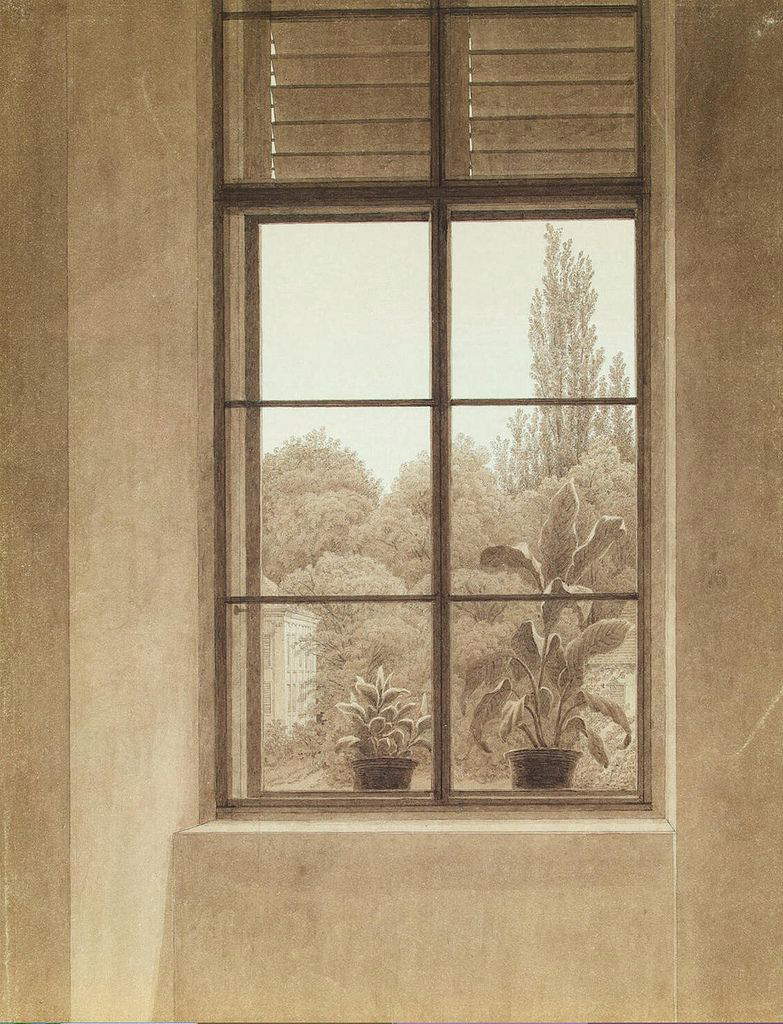

First of all, the reappropriation of space by nature takes place through reflections: in painting number 7 of the 2018 Eschatos series, a vast puddle of water reflects the uncovered steel roof of a shed, with the result that, to invoke Ferretti again, “the sky is above and below” and the water is transformed into a mirror, with all that this entails on a symbolic level. And then, it is nature itself that enters the architecture: in Eschatos the element of the window open to a garden invaded by weeds that sometimes climb the glass, the jambs, the walls is recurrent. The need to return to nature after the fumes of civilization was characteristic of the Romantic artist, and it seems to be delineated also in the art of Andrea Chiesi (who, after all, lives and works in nature). And exactly as it was for Romantic artists, for Andrea Chiesi too the window is the connecting element. “Emblematic of the Romantic vision of reality,” Fernando Mazzocca, a great scholar of Romanticism, recently wrote, the window becomes the lens through which the artist sees beyond his studio and, therefore, is the means by which he returns his own “strongly internalized vision” of reality. Just as the window is the place from which Leopardi gazes at the sky, the flowerbeds, the avenues of the garden in front of the family palace, and is thus the element through which the view can inspire him with the “sweet dreams” vague in the Ricordanze, in the same way, Mazzocca recalls, for painters the window is an instrument of observation that ends up becoming their self-portrait: it is “the magical threshold that separates them from reality,” the limit between the self and the outside, between the experienced and the felt.

From the account of Kurt Waller, a journalist writing in a Viennese paper in the early nineteenth century, we know that Caspar David Friedrich worked in a studio from which he enjoyed a “heavenly panorama” of the Elbe, the river that washes Dresden. Just outside Friedrich’s window, a wonderful view opened up: verdant parks, the teeming riverfront, the city center. Yet, that view so extolled by the journalist turns out to be barely hinted at in some of the artist’s paintings executed from inside the studio, and starring that very window: the Elbe landscape, beyond Friedrich’s window, is bathed in a clear light and appears distant, unreachable. The real landscape is transfigured into an unquenchable longing for infinity, and the window is at once a gateway that the artist cannot overcome, but it is also a tool beyond which to see new and unexplored worlds. This desire had become even more ardent and impossible when the German artist, burdened by precarious health conditions, went to Teplitz (today’s Teplice in the Czech Republic) to benefit from thermal cures: the luxuriant nature glimpsed in a view from the window of his hotel makes the window itself a symbol of a nostalgic awareness of the unattainability of a goal. Perhaps the vertigo of Sehnsucht is lacking in Chiesi, but one senses that there is a world on this side of the window and a totally different universe once one crosses the threshold. Two worlds separated even visually: the orderly geometries of the window and the fertile disarray of nature.

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Saturday 19-07-03 (2004; oil on canvas, 100 x 140 cm) |

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Friday 26-09-03 (2004; oil on canvas, 100 x 140 cm) |

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Eschatos 7 (2018; oil on linen, 140 x 100 cm) |

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Eschatos 11 (2018; oil on linen, 70 x 50 cm) |

|

| Caspar David Friedrich, Window with a View of a Park (1836-1837; graphite and sepia on paper, 398 x 305 mm; St. Petersburg, Hermitage) |

However, Andrea Chiesi’s painting is always an alternation of thresholds, it is always a constant quest in constant evolution: in his production there is never anything that is the same as something done before. A series, once finished, is destined not to return, because it gives way to new and more urgent and pressing solicitations, perhaps arising from a journey or a novel experience, and which end up preventing the artist from returning to the past. Claudio Musso, who curated a recent 2016 solo exhibition of Andrea Chiesi’s work in Bologna, wrote that, in his work, “the rhythm of observation is marked by the crossing of thresholds, one after the other. Doors, windows, curtains, bridges, railway lines, elevated roads: presences that cluster ”occupying the extension of the visual spectrum and at the same time describing its linear development." Presences that find a conceptual correspondence in the modus operandi of the artist, whose imagery is constantly enriched with new images, pondered following long and slow meditations. A necessary process for that transfiguration of the real that Andrea Chiesi seeks with constancy. And in all this one also grasps a deeply intimate dimension.

A dimension that, unfailingly, intrigues me. When one looks at paintings with abandoned warehouses stretching almost to the point of occupying the visual horizon, one often has the feeling of being in the center of the nave of a great Gothic cathedral. Or perhaps it is simply a feeling caused by the sense of mysticism that inexorably hovers among the Chiesi ruins. So I ask him if there is an attempt to establish some kind of relationship with those who find themselves admiring his works, if there is a direct message addressed to the viewer, if the ability to evoke certain impressions is intentional. His answer is negative: in those paintings, each of us can see what we want, every feeling is valid, every reference worthy of discussion. Art, said Andrea Chiesi in the aforementioned interview with Simone Menegoi, must not reveal. It must leave the mystery.

Andrea Chiesi was born in Modena on November 6, de 1966. He lives and works in San Pancrazio in Modena. Trained as a self-taught artist and without having studied at Academies, he began his career as an illustrator and draughtsman and then came to painting. To his credit he has residencies in New York, Berlin and Beijing, and is a winner of the V Cairo Prize (2004), the Gotham Prize 2012, the I Terna Prize (2008) and the XXXVIII Suzzara Prize (1998). He has collaborated with, among others, Giovanni Lindo Ferretti, writers Emidio Clementi, Giorgio Casali, Ugo Gornia and Simona Vinci, and music groups C.S.I Consorzio Suonatori Indipendenti, Massimo Volume and Officine Schwartz. His solo shows have been held in various galleries in Italy and abroad, and he has exhibited at the “Emilia Romagna” section of the Italian Pavilion of the Venice Biennale in 2011, at the Italy-China Biennale in 2016 and 2014, as well as in group shows at the Galleria Estense in Modena, the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, the Fondazione Cini, the Palazzo Reale in Milan and several other museums.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.