It now dates back to the summer of three years ago the news, also reported in the pages of Finestre Sull’Arte, of the accident of an Italian tourist visiting the Serralves Museum in Porto, Portugal. The cause of the mishap, which cost the unfortunate man a brief hospitalization, was all due to the perceptual deception triggered by the works of Anish Kapoor (Mumbay, 1954). In the case in point, the unwary visitor, bewitched and attracted by Descent into Limbo (1992), a work presented at Documenta IX in 1992 and then re-presented at the Portuguese museum years later, plummeted inside the work, an eight-foot hole in the floor, painted with a special black pigment, Vantablack, of which Kapoor has been granted exclusive use in recent years. In contrast to the upward movement of the souls in limbo, rescued by Christ in Andrea Mantegna’s work(Descent into Limbo, 1492), from which Kapoor is inspired, the installation’s accidental descent into the void, described as “tragicomic” by Roberta Scorranese in Corriere della Sera (Aug. 21, 2018), is perhaps the definitive and extreme fulfillment of the poetics of the Indian artist, a star of international contemporary art.

Kapoor is among the leading exponents of British sculpture and is part of what Renato Barilli, also including Tony Cragg, Roger Deacon, Bill Woodrow, and Julian Opie, has called the “extraordinary quintet” of so-called New British Sculpture (R. Barilli, Before and After 2000. Artistic Research 1970-2005, Feltrinelli Editore, Milan, p. 98). Coming from a multiethnic family, Kapoor came into contact with music and art at a very young age, without feeling any particular vocation. Then, at the age of nineteen, moving to London, where he still resides, he attended Hornsey College of Art in London (1973-77) and then Chelsea School of Art (1977-78). He realized only then that the art world would be his terrain for shaping enigmatic structures that stimulate curiosity, sensoriality and deceive, as seen in the Portuguese affair, our perception, through the use of disparate and skillfully composed materials to lead artist and visitors, together, to the discovery of the unknown.

The creative process is described by Kapoor as a true dialogue with matter. Just as in the conversation between patient and analyst, themes just brought to light are researched and then investigated, so the encounter between artist and material gives rise to a third entity, the work, which captures attention by posing more questions than answers. Referring to the aforementioned painting by Mantegna, Kapoor’s most beloved work ever in the history of art, the artist dwells on Christ and the cross-crowned staff he holds and establishes parallels with the artist’s work. In the same way as the Savior reaching into the darkness, the artist would be that individual capable of finding the indispensable tools to conduct a shamanic journey of knowledge.

Kapoor’s early works, made from 1979-80, have as their dominant element pure pigment, often red, considered as true ritual matter, close to blood and earth. This association is evident in Mother as a Mountain (1985), where the mountain takes on the features of a female genital apparatus, in allusion to the moment of birth. These are geometric shapes, generally small in size, which, underneath the colored surface conceal a wooden core. The cultural, symbolic and visual references of the series, called 1000 Names, are to be found in the complex Indian culture and in some of the emblematic places Kapoor had the opportunity to visit in his youth. Thus, the forms that would later be characteristic of even his more mature works begin to take shape in these early years. Concave or convex figures take on symbolic meanings and are the result of visual fascinations of natural landscapes such as mountains and caves or artificial ones as in the case of ritual places created by man throughout history. In a conversation with Greg Hilty and Andrea Rose, the artist mentions the Elephanta cave-sanctuaries, not far from Mumbay, probably made between the fifth and sixth centuries AD, and the eighteenth-century Jantar Mantar astronomical observatory in Jaipur, India. This site, of which formal reminiscences can perhaps also be traced in some of Kapoor’s sculptures, ties in with the artist’s idea that sculptural installations in the environmental context are the connecting element between earth and cosmos.

To exemplify this concept, Kapoor calls into question one of the best-known works of Romanian artist Costantin Brâncu�?i, La colonne sans fin (1937), a construction almost thirty meters high, made by superimposing more than 15 modular steel elements to exaggerate the structure’s sense of verticality, in search of direct contact with space. Kapoor himself makes his Endless Column (1992), ideally overcoming the boundaries of the floor and ceiling with a cylinder covered in red pigment, and he probably takes up from Brâncu�?i the use of polished metal, already present in works such as Untitled (1999), a polished bronze reminiscent of the Romanian’s Maiastra (1912-15). Yet Kapoor surpasses Brâncu�?i, in the direction of a research that is not limited to the essentiality of forms and contemplation but aims at the active, emotional and physical involvement of the viewer.

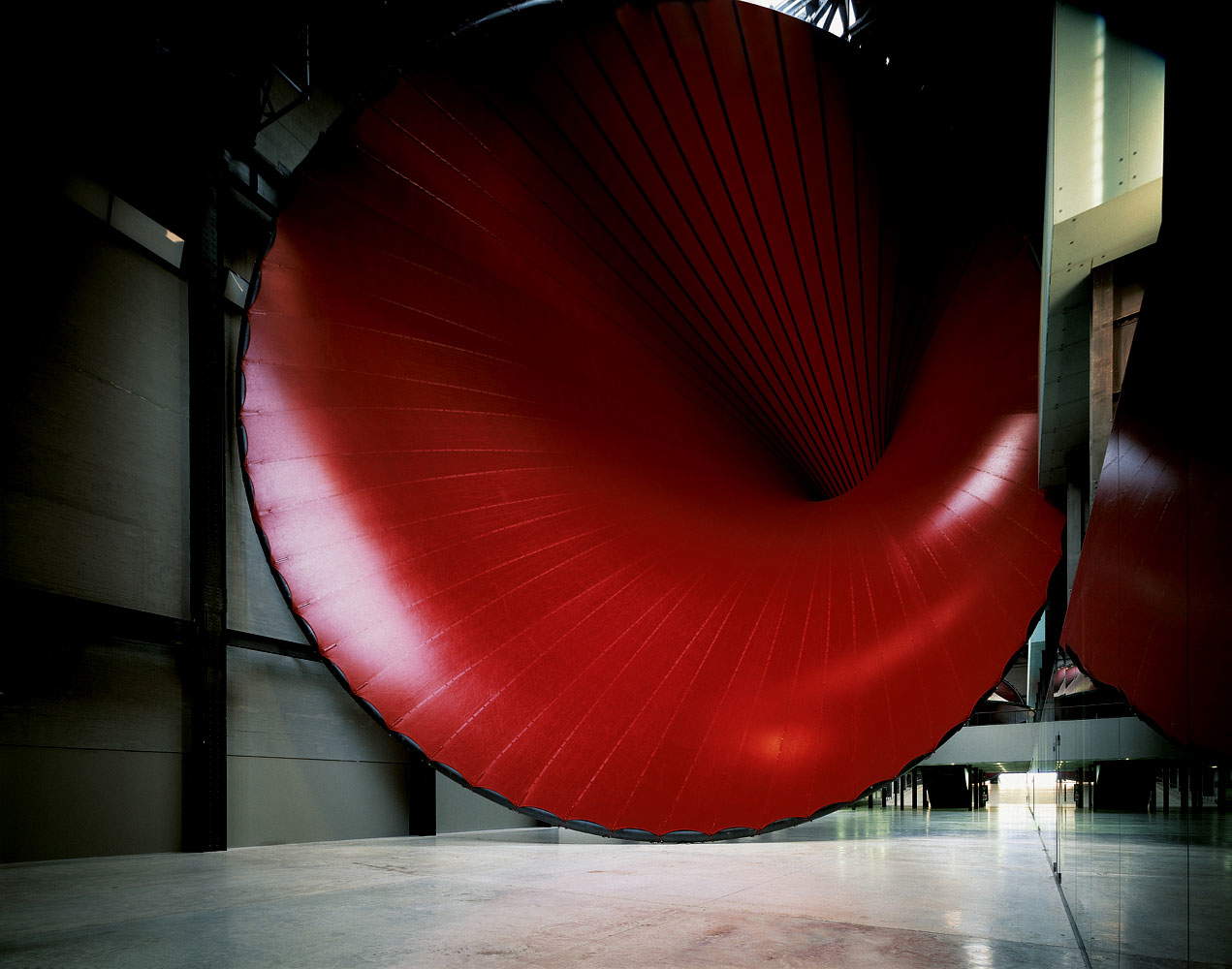

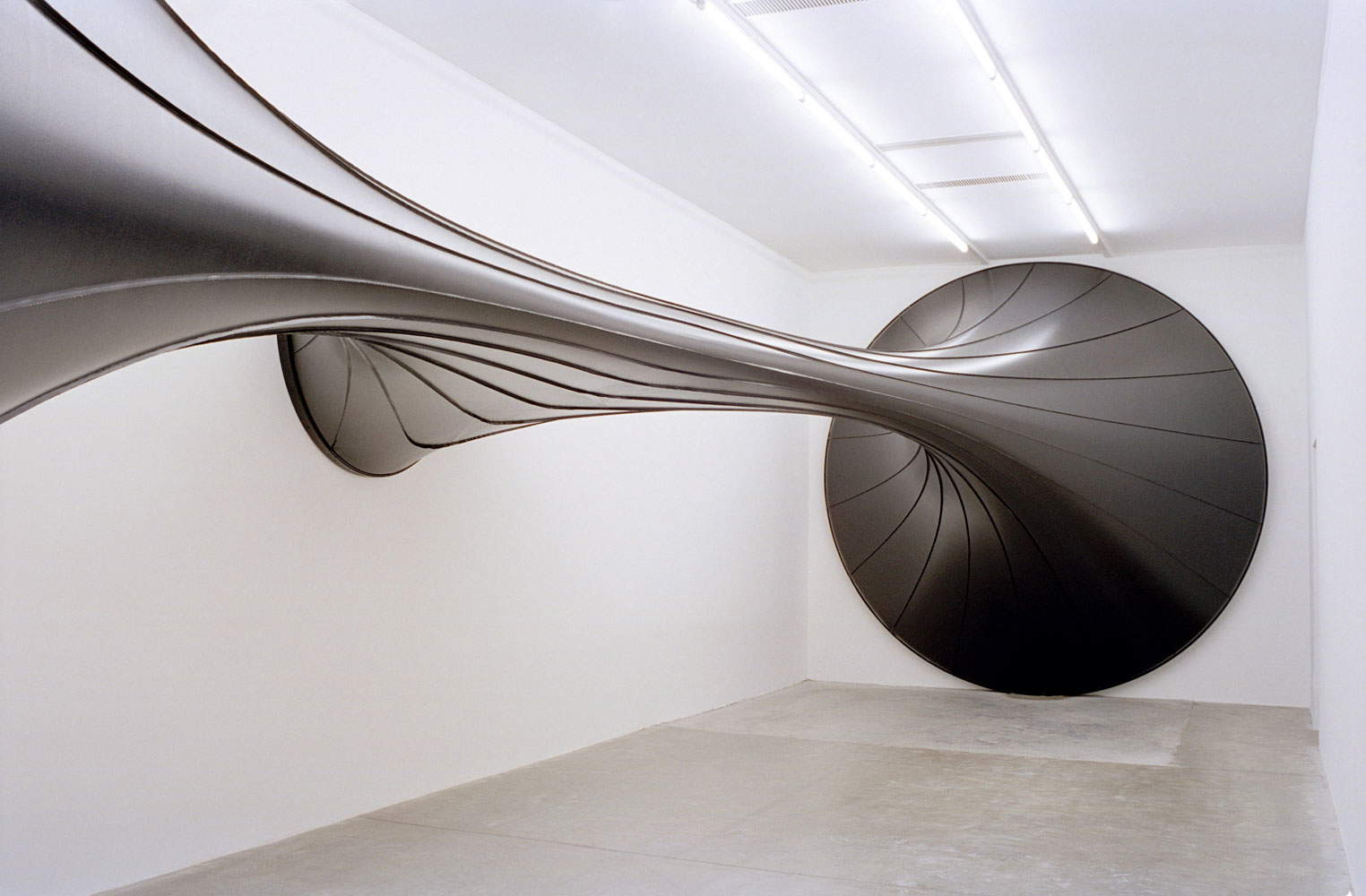

Also as a function of this, since the 1990s Kapoor’s works have taken on monumental proportions and invaded institutional spaces dedicated to art, the natural and urban environment. His museum interventions include at least the installation in the Turbine Hall of London’s Tate Modern, Marsyas (2002), inspired by the bloody mythological tale of the satyr Marsyas and Titian’s famous painting of the same subject, which can be found on the artist’s website accompanying the design material. Ideally following the London work is the Parisian one, Leviathan (2011), designed for the interior spaces of the Grand Palais. Both structures, consisting of steel and pvc rings of two different shades of red, envelop the viewer in an environment of undefinable boundaries and ideally immerse him or her inside the body of a living being, appealing to one’s sensibilities and leaving one stunned both physically and psychologically. To these two works, one can also approach, in terms of materials and aesthetics but not in terms of mode of fruition, Widow (2004) or Dismemberment, Site I (2003-2009), placed in natural space in New Zealand.

In the city context, however, are some of the most globally known interventions. Cloud Gate (2004), installed at Chicago’s Millennium Park, is one example. Its shape is that of an elliptical arch, a bean to some, of polished and reflective steel, inspired by the appearance of liquid mercury. Now a regular stop for residents and tourists from all over the world, the Cloud Gate has been visited by hundreds of millions of people, fascinated by the object that collects and returns the cityscape and warps the image of those who decide to “dive in.” Kapoor has defined this work as a democratic place, open to all, whose fortune lies not so much in the object itself as in the extraordinary relationship the public naturally has with this sculpture and others that have been placed in the urban environment, such as Sky mirror (2006).

Kapoor’s work, so far traversed through some of the most significant works, makes use of and experiments with various other materials not yet named: among them some minerals, paint or even red wax, particularly striking in Shooting Into the Corner (2009-13) where a cannon explodes shreds of matter against the wall. But regardless of the technique employed, what remains constant in Kapoor’s work is the ability to call his interlocutor into the work, challenging everything known and challenging his sensations, to the point of leading into a void laden with potential. The reading of each work thus remains open, and each creation is not the end point of Kapoor’s research but rather the beginning of a perceptual journey capable of shaking all certainty.

The author of this article: Stella Cattaneo

Specializzanda in Storia dell'arte e valorizzazione del patrimonio artistico presso la Scuola di Specializzazione dell'Università degli studi di Genova. Attualmente curatrice di Casa Museo Jorn (Albissola Marina, Savona), ha partecipato a convegni e giornate di studio all'Università di Losanna e all'Università di Genova (2019) e a seminari internazionali di museologia (école du Louvre, 2018). I suoi interessi di ricerca si rivolgono prevalentemente all'arte contemporanea con particolare attenzione al periodo del secondo dopoguerra e all'opera di Yves Klein.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.