It is almost unbelievable to think that Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Naples, 1598 - Rome, 1680) was only twenty-three years old when he was about to create one of his most celebrated masterpieces, the Rape of Proserpine: yet, despite his very young age, he was already an accomplished sculptor, and he had already had the opportunity to work for the powerful patron who had commissioned him to create the very famous group in the Borghese Gallery. He had in fact been entrusted with the commission by Cardinal Scipione Borghese (Rome, 1577 - 1633), one of the most prominent men in Rome, at that time Camerlengo of the Sacred College, having been for sixteen years Secretary of State to the pope, as well as a refined collector, in perennial search of the best works of contemporary artists. In 1606, the cardinal had begun construction work on his villa, what is known as Villa Borghese Pinciana and is now the site of the Borghese Gallery, and it was obviously necessary to decorate it in the most suitable manner: the first achievements of the very young Bernini had attracted the attention of the most discerning collectors, so much so that Scipione Borghese, as early as 1618 (the artist was then only twenty years old), hired him with the specific purpose of creating sculptural groups to be included in the new villa. The Rape of Proserpine was the second of the four Borghese groups, and Bernini began work on it a few months after completing the first, theAeneas, Anchises and Ascanius, finished in 1619. In fact, in October of that year there is a document attesting to the delivery of a large block of marble to the workshop of Pietro Bernini (Sesto Fiorentino, 1562 - Rome, 1629), Gian Lorenzo’s father: it is presumably the one from which the Rape of Proserpine would take shape, which was begun in the summer of 1621.

Scipione Borghese had been very satisfied with the first group, and had therefore decided to continue his collaboration with Bernini, commissioning him to make a further sculpture of a mythological subject, again taken from Latin literature. So if for theAeneas, Anchises and Ascanius the literary reference was Virgil with his Aeneid, for the new group the subject came from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. This is one of the most famous fables in Greco-Roman mythology: Proserpine (or, in Greek, Persephone) was the beautiful daughter of Ceres (Demeter), goddess of the harvest. She fell in love with Pluto (Hades), the god of the underworld, who wanted to make her his at all costs. So, while the young girl was intent on plucking flowers from a meadow, the lord of the underworld abducted her, taking her with him into the bowels of the earth, and leaving her mother, in despair, to wander for nine days and nights looking for her. After knowing, on the tenth day, the fate of his daughter, Jupiter (Zeus), the king of Olympus, tried to get his brother Pluto to return Proserpina to her mother. However, the girl had already eaten pomegranate grains, the food of the dead: for that reason, she could not permanently return to the world of the living. In any case, Jupiter managed to “broker” an agreement, ensuring that Proserpine could return to earth for six months of the year. For the remaining six, however, she would remain with Pluto, whose bride she would become, in the underworld. The ancients used this myth to explain the alternation of the seasons: Proserpina’s arrival on earth corresponded to the good season, while her descent into the underworld gave rise to autumn and winter.

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Rape of Proserpine (1621-1622; marble, height 255 cm without base; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

This is the account of the moment of the rapture in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, here in Mario Ramous’ translation: “Proserpina / was amusing herself by picking violets or white lilies, filling with boyish zeal the baskets and the flaps / of her robe, competing with her companions to see who could pick the most, / when in a flash Pluto saw her, fell in love with her and abducted her: / so precipitous was that passion. Terrified the goddess / invoked with a heartfelt voice her mother and companions, but more her mother; and because she had torn the lower flap / of her robe, it loosened and the gathered flowers fell to the ground: / so much was the whiteness of that youth, that in her heart / of a virgin even the loss of the flowers caused her grief. / The abductor launched the chariot, inciting the horses,/ calling them by name, waving on their necks / and on their manes the reins with the gloomy color of rust; / he passed swiftly over the deep lake, over the ponds of the Palycians / exhaling sulfur and seething from the cracks of the bottom, / and there, where the Bacchiads, natives of Corinth that is mirrored / in two seas, erected their walls between two inlets. / Between the fountains Cìane and Arethusa Pisea there is a stretch of sea, / which narrows, enclosed as it is between two narrow tongues of land: / here, most notorious among the nymphs of Sicily, / Cìane lived, and from her that lagoon also took its name. / From the waves emerged the nymph to the waist, / she recognized the goddess: ’You will not go far,’ she said; / ’son-in-law of Ceres you cannot be, if she does not consent: / ask her you should, not kidnap her. If I may / compare great and small, I too was by Anapi beloved, / but I was his bride after I was begged, not terrified’. / So he said, and spreading his arms wide he tried / to stop them. The son of Saturn no longer restrained his rage: / by stirring up the terrible horses, he brandished with all the vigor / of his arm the royal scepter and plunged it into the depths / of the whirlpools: at that blow a gap up to Tartarus opened in the earth / and the chariot sank into the chasm disappearing from sight.”

Bernini depicts the climax of the tale, the most excited and violent moment: the moment of abduction. Hades, proud, mighty, and muscular, has grabbed the girl, who tries to escape and wriggle out of the god of the underworld’s tight grip: the hand sinking into Proserpina’s thigh, with his fingers exerting their pressure on the young girl’s flesh, is perhaps one of the most famous and celebrated details in all of art history. She struggles, kicking, with her legs trying to lift herself up to find an escape route, her hands flailing, one striking Hades’ bearded face. His longing, vaguely ecstatic expression betrays a slight motion of fatigue: if one read only his gaze, one might perhaps think that the daughter of Ceres might be able to break free, sooner or later. But, looking at the rest of the body, one senses that Proserpina’s feat is quite difficult, if not impossible: the god is in fact firmly planted on his sturdy legs, the left is firmly pointed forward to act as a pivot, and the right is instead further back to balance the position so that Hades does not lose his balance. The torso, muscles sculpted and well-defined, bends backward to work lats and abdominals, called upon to support the arms, which tighten in a circle so as to make the grip more effective: with his left hand, Hades encircles Proserpina’s back so that she cannot make herself fall backward to free herself and, at the same time, so as to hold her close enough to him to make her more vulnerable, while with his right hand he performs the same movement by encircling her legs so as to restrict her movements. The only hope, for her, is to lean forward: Bernini catches her, in fact, as she attempts a movement by pushing herself with her shoulders and helping herself with her arm. The attempt, however, is in vain: not least because, moreover, Hades has brought with him Cerberus, the monstrous three-headed dog, guardian of the underworld, ready to block Proserpina from behind and, moving his three heads in three different directions, careful to check that no one will come over to hinder Hades’ plans. Thus, she can do nothing but let out a cry that lets out, at the same time, her shame at having been denuded (in fact, we notice the veil slipping from her body revealing her soft form: a faithful transposition of the detail of Ovid’s tale), her terror at the violence she is undergoing, and her discouragement at realizing that no one can help her.

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Rape of Proserpine in its room at the Galleria Borghese |

|

| View of the protagonists from below |

|

| Detail of the figure of Proserpine |

|

| Pluto’s fingers sinking into Proserpine’s flesh |

|

| Cerberus checks with his heads |

|

| Cerberus watches over Proserpine |

Hundreds of pages have been spent on this extraordinary sculpture, one of the pinnacles of world art history: many have been the scholars who have tried to render, relying solely on the evocative power of the pen, the force of Bernini’s unparalleled virtuosity. Ursula Schlegel has described the unfolding of the abduction with good effectiveness: “The Pluto wanted by Bernini comes up from behind, to seize Proserpina unaware, and grasps and blocks her with both arms while his scepter naturally in this action falls to the ground. With his right arm he encircles her legs at thigh level, holding her tightly with his left at the waist. And in this the goddess’s robe, compressed, partly departs from her body fluttering above her right shoulder, and partly falls back between her and Pluto’s left arm in many clumps of folds behind the goddess’s back and between her legs. Proserpine’s terror cannot be given a more convincing form: turning her torso backward, the goddess presses her left arm vividly in front of Pluto’s eyes and against his left eyebrow, repelling him and throwing her right arm up, like a cry, while her legs are prevented by Pluto’s force from any movement.” Luigi Grassi left us an interesting summary of the contrast between Pluto’s and Proserpina’s expressions: “it is more outward and almost carnivalesque the mask of Pluto, in accentuated contrast to the soft and sensuous tenderness of Proserpina, rich in pictorial effects, effective in that rhetoric of the piant that expresses, especially in the face, a now more sly search for the affections.” One of Bernini’s leading scholars, Maurizio Fagiolo dall’Arco, has devoted attention to the figure of the Cerberus, which would also rise to a symbolic role: “a singular invention is that Cerberus on which the sculptural group leans: the three heads of the mythical monster are also meant to indicate the complex dynamic construction of the group, the three directions of space.”

Anna Coliva, on the other hand, has produced essays on the technical characteristics of Bernini’s group, and reading her words one can in a way guess how Bernini reached heights of virtuosity precluded to all his contemporaries: “in the Rape of Proserpine, the never-equaled effect of soft, sensual yielding of the marble in the leg of the maiden under the fingers of Pluto is due to the uniform rough appearance with which all the ’skin’ of the woman is treated, which increases the naturalistic effect of the flesh; this softness is even more enhanced by contrast with the other surfaces worked by different tools: the effect of the fabric is treated by rasp; the hair of the Cerberus and the ground by step, the foliage by chisel, with the help, in places, of the drill.” The wonder of the Rape of Proserpine was also the object of the attentions of Cesare Brandi, who during his art history lectures addressed an invitation to his students to understand whence the power of the young Bernini’s work originated: if you think of the larger proportions from life and the extreme fineness of the surfaces, consider the commitment to which Bernini submitted himself. Again in this work the Mannerist attack is evident, supplemented, however, by classical examples. Classical culture is visibilissin the way he organized the three figures, which give rise to a spiral that is, however, much less accentuated and regularized than is the case, for example, in Giambologna’s Rape of the Sabine Women. In the Rape of the Sabine Women, it is very clear that the spiral on which the group is built does not tend to make the internal spatiality of the group dilate, and the limbs that come out are extrapolations in the same way as the statues placed in the niches from which an arm, a leg and the head itself come out; that is, they are mentally recomposed and reabsorbed into the niches, so Giambologna’s group and reabsorbed into the generating spiral of the group itself. Regarding the necessary comparison with Giambologna ’s Rape of the Sabine Women (Douai, 1529 - Florence, 1608), Brandi’s words were echoed by those of André Chastel: one need only compare Bernini’s Rape of Proserpine with Giambologna’s Rape of the Sabine Women, from half a century earlier, to realize how Bernini expands the limits of the block in all senses, opens the composition in all directions, rejects the dispersion of attention to which Mannerist sculpture yielded, and returns to the principle of the unity of point of view and, therefore, of action.

|

| The face of Proserpine |

|

| The face of Pluto |

|

| The heads of Cerberus |

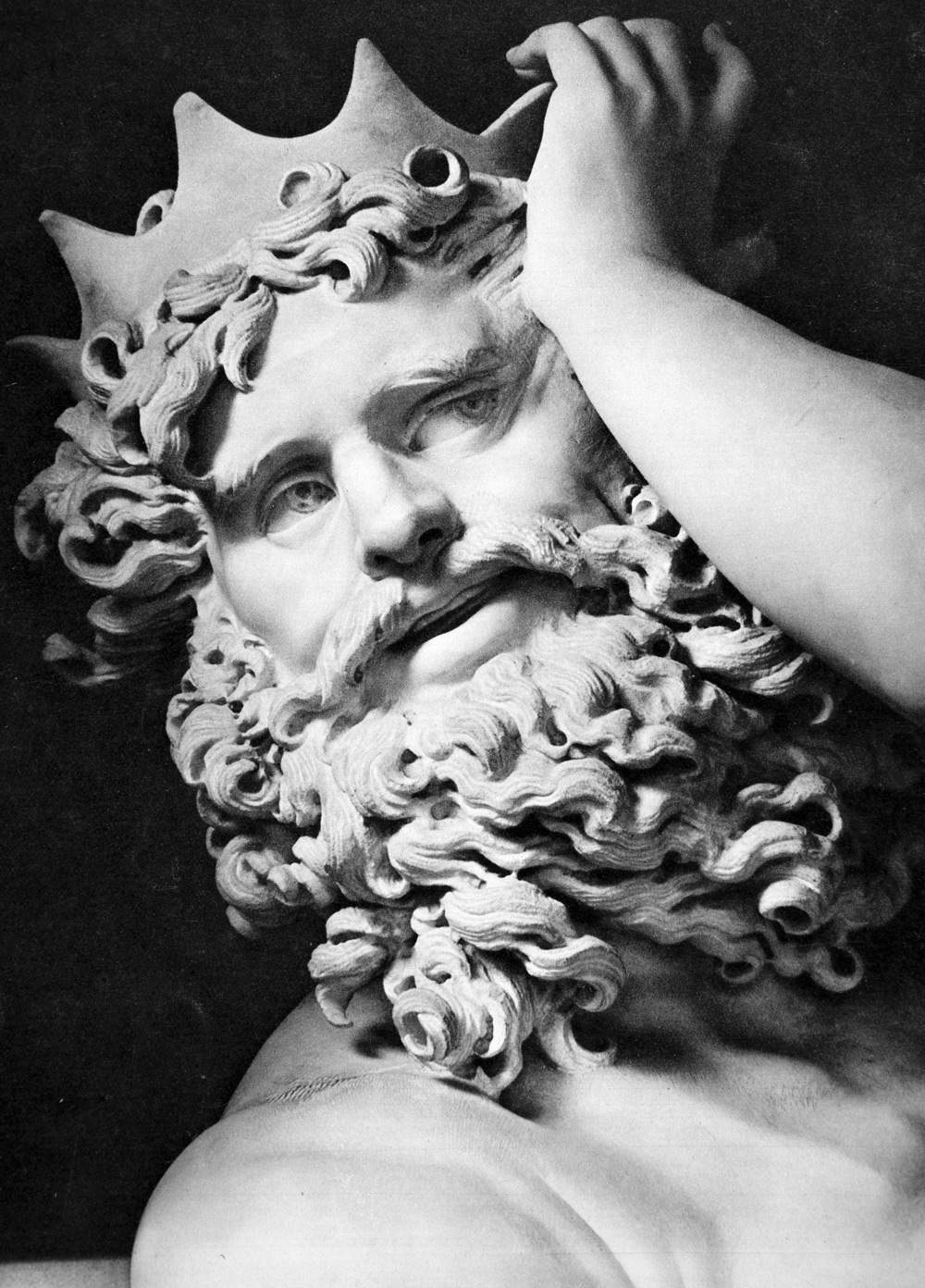

Indeed, many have also discussed at length the models to which Bernini may have drawn inspiration in devising his masterpiece. The first references must be found in classical art: still Fagiolo dell’Arco pointed out how classical fables abounded with scenes of escape, abduction and assorted violence that must have provided a vast repertoire for the young Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Many have therefore suggested that, for the face of Proserpina (of which, moreover, there is also a terracotta fragment preserved at the Museum of Art in Cleveland: it is thought to be a preliminary study of the figure), the sculptor perhaps drew inspiration from the face of one of the Niobids from the famous group now in the Uffizi, but in Bernini’s time kept in the garden of Villa Medici in Rome: the set of sculptures, datable to between the first century B.C. and the first century A.D., had been discovered in 1583 and purchased shortly thereafter by Cardinal Ferdinando de’ Medici (later to become Grand Duke of Tuscany), who immediately placed it in the villa’s garden (it was instead transferred to Florence in 1770, and since 1781 the statues have been in the Uffizi). A classical reference could also be found for Pluto’s head: in particular, the artist may have drawn inspiration from the Centaur ridden by Cupid, a Roman marble now in the Louvre but at the time in the extraordinary collection of Scipione Borghese. It would, moreover, also be a symbolic parallel, since Pluto himself was blinded by insane love for Proserpine at the time he abducted her. Scholar Matthias Winner has especially related the hair styles of the centaur and Pluto, noting how the latter’s resembles the mane of a lion: this would be yet another symbolic device to suggest the idea of the “solar lion,” an allegory of the sun in the six months of winter.

Again, the relations of the Rape of Proserpine with Mannerist sculpture should be emphasized. It has already been mentioned how Bernini may have looked to Giambologna’s Rape of the Sabine Women: however, Bernini managed to update and innovate in a disruptive and revolutionary way that lofty model. The first innovation concerns, as already anticipated, the return to the privileged point of view: if Giambologna’s work had been conceived to be observed from different positions, Bernini, on the contrary, wants the viewer to observe the group frontally, placing himself in front of the two characters so as to catch, at the same time, the expressions of the protagonists (Cerberus included: the frontal view causes one of the heads to protrude behind Proserpina’s left foot) and their excited movement. Not only that: Bernini was able, thanks to his skill in working marble, to infuse the material with a fullness that makes it come alive, as Alessandro Angelini has well explained: “to the frigid tension of the anatomies carved by Giambologna, Bernini contrasts effects of a new, fleshy sensuality. In the soft flank of Proserpine, on which Pluto sinks his robust fingers, one catches Gian Lorenzo’s early efforts to achieve the effect of soft marble as if it were wax. The velvety hair of the maiden, the shaggy beard of Pluto, moved by the wind and the soft waving of the two heads, seem as if to merge with the surrounding air.” Angelini found in Pieter Paul Rubens (Siegen, 1577 - Antwerp, 1640) a precedent, and particularly in the Susanna and the Old Men that the Flemish painter probably made for Scipione Borghese himself.

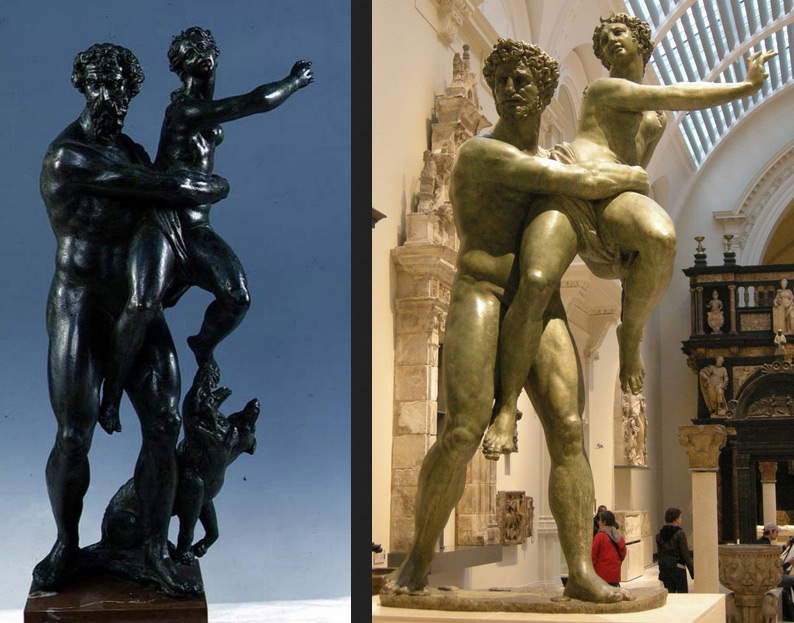

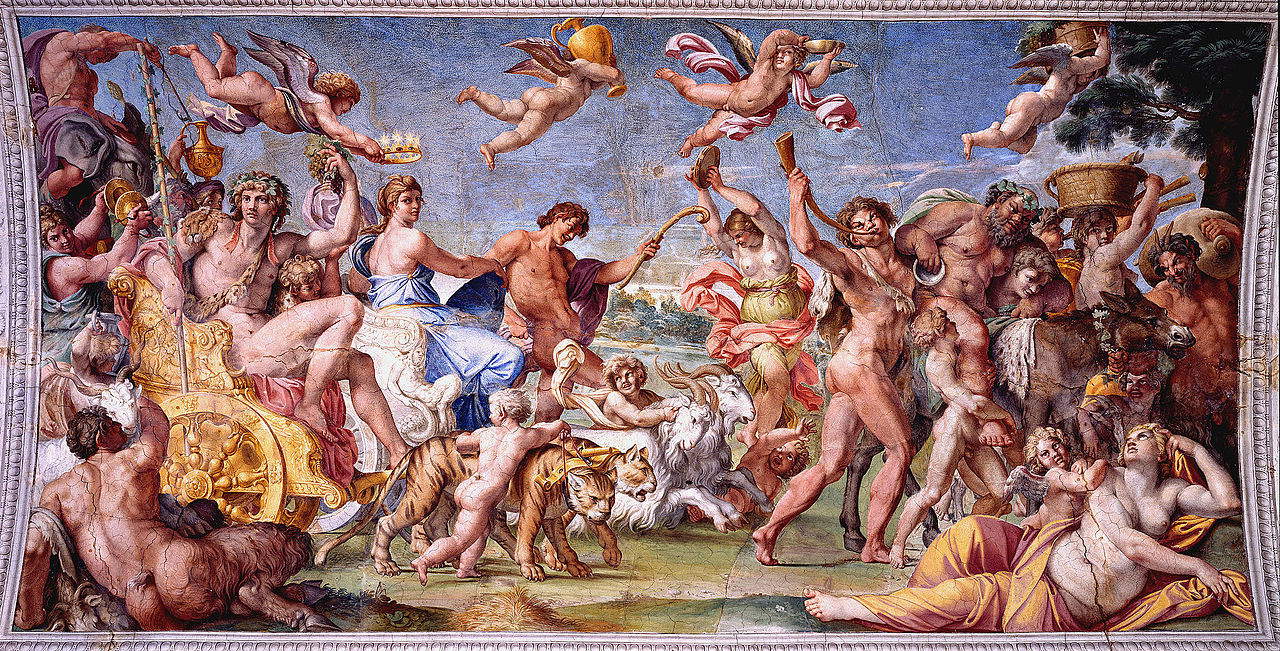

It has also been identified by many, in addition to Giambologna, another Mannerist precedent, which is less well known: it is a small bronze, datable around 1587, by Pietro Simoni, known as Pietro da Barga (documented from 1571 to 1589), which depicts precisely the Rape of Proserpine and which is now preserved in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence. It thus seems that the invention of Pluto’s grasping of Proserpina as she flails her legs and thrusts her arms forward, and further below Cerberus blocks all escape, dates back to Pietro da Barga: and in turn, Pietro da Barga had taken up an idea of Vincenzo de’ Rossi (Fiesole, 1525 - Florence, 1587), who some 20 years earlier made a Rape of Proserpine, now in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, where it almost seems as if Pluto is holding the young woman, who seems to us to be sitting, rather than shaking, on his arms. In a 1985 article, the aforementioned Matthias Winner had wondered why Bernini had looked to an artist like Pietro Simoni, who was an excellent sculptor but not among the most prominent of his time. To answer this, Winner had leafed through the Giuntina edition (1568) of Giorgio Vasari’s Lives, opened by a letter from historian Giovanni Battista Adriani (Florence, 1511 - 1579) in which the great Greek sculptor Praxiteles is said to have "held Praxiteles as a greater master“ and to have produced, among other works, a ”robbery of Proserpine.“ According to Winner, Pietro da Barga’s bronze can ”be interpreted as a humanistic reconstruction of Praxiteles’ lost bronze group," and consequently Bernini, who knew Vasari as well as Pietro da Barga, probably wanted to propose his own attempt to bring Praxiteles’ sculpture back to life. And again, Bernini could not help but look to his contemporaries: Angelini spoke of Rubens, while Rudolf Wittkower was able to pick up references to the Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne, a masterpiece by Annibale Carracci (Bologna, 1560 - Rome, 1609) who in Rome decorates the vault of the Galleria Farnese. In particular, Wittkower suggested how, in tying the Rape of Proserpine to Annibale Carracci’s reading of classicism, we can identify the point of transition from Mannerism to Baroque. "In Pluto and Proserpine,“ Wittkower wrote, ”Bernini looked at classical antiquity through the eyes of Hannibal. The voluptuous and at once cold beauty of Proserpine’s body finds close analogies with the vault of the Galleria Farnese, and the same is true of the hypertrophic anatomies of her seducer. Moreover, his head, with its non-classical hair and beard, which almost resembles a bush, is an accurate marble counterpart to the Gallery’s faux-marble caryatids. And Cerberus is also an adaptation of Paris’s dog in the ceiling fresco. Accurate realistic observation and classical influences are subordinated to Hannibal’s disciplined interpretation of the antique: this was the formula through which Bernini freed his style from the last vestiges of Mannerism."

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Head of Proserpine (1621-1622; terracotta, 15.2 x 10.3 cm; Cleveland, Cleveland Museum of Art) |

|

| Roman art, Daughter of Niobe (1st cent. BC-1st cent. AD; Pentelic marble, height 181 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

|

| Roman art, Centaur ridden by Cupid (1st - 2nd cent. AD; marble, 147 x 107 x 52 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

|

| Giambologna, Rape of the Sabine Women (1574-1580; marble, height 410 cm; Florence, Loggia dei Lanzi) |

|

| Pieter Paul Rubens, Susanna and the Old Men (1607; oil on canvas, 94 x 66 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Left: Pietro Simoni da Barga, Rape of Proserpine (c. 1587; bronze, height 59 cm; Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello). Right: Vincenzo de’ Rossi, Rape of Proserpine (c. 1565; bronze, 230 x 142 cm; London, Victoria and Albert Museum. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini) |

|

| Annibale Carracci, Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne (c. 1597-1600; fresco; Rome, Palazzo Farnese) |

There has also been debate about who might have influenced the choice of subject. What is certain is that on the original base of the work, carved in July 1622 by the carver Agostino Radi and now lost (the current one was made in 1911 by the sculptor Pietro Fortunati), appeared a Latin couplet that read “Quisquis humi pronus flores legis, inspice saevi / me Ditis ad domum rapi” (“O you who, stooping, gather flowers, look at me / who am abducted to the abode of the cruel Ditis”). The author of the short lyric was Maffeo Barberini (Florence, 1568 - Rome, 1644), future pope Urban VIII (he would become one in 1623) as well as Bernini’s great patron. Barberini had composed, between 1618 and 1620, a manuscript entitled Dodici distichi per una Galleria, in which, through epigrams such as the one above, twelve paintings in an imaginary gallery were described. It seems likely, therefore, that the future pontiff’s composition could have somehow suggested the choice of subject. The myth of Pluto and Proserpine, with its allegorical reference to the rebirth of nature and, therefore, to the theme of regeneration, was well connected, as Winner observed, to the desire to affirm that, with the marriage of Marcantonio II Borghese and Camilla Orsini and the imminent birth (in 1624) of their son Paolo, the Borghese family had obtained the possibility of regeneration. We move, however, into the realm of pure hypothesis.

The work left Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s workshop in September 1622 and was immediately transported to Scipione Borghese’s Pincian villa. However, it did not remain there for long: a few weeks later, the cardinal donated the sculptural group to Ludovico Ludovisi (Bologna, 1595 - 1632), cardinal nephew of Pope Gregory XV, who had passed away in the summer of that same year. There is in fact an inventory of Cardinal Ludovisi, dated November 2, 1623, which mentions the work as “a marble Proserpina that a Pluto carries off her about 12 palms high in about et un can trifauce with a marble pedestal with some verses of face.” We do not know with certainty the reasons for the gift: some speculate that Scipione Borghese had to reciprocate a favor received from his young colleague, others think that the powerful cardinal had wanted to deprive himself of Bernini’s masterpiece in order to mend good relations with the Ludovisi family, with whom there was bad blood (in any case, it is highly likely that it was a diplomatic gift, of particular importance). The sculpture remained the property of the Ludovisi family for centuries: when the villa became public property and was demolished to allow the construction of roads and buildings in the Via Veneto district, the collection was largely acquired by the state. That was in 1901, and the Rape of Proserpine, like so many other statues in the Ludovisi collection, was placed in the Museum of the Baths of Diocletian: it was in 1908 that it was decided to move it to the Borghese Gallery, so that it could join Bernini’s other bourgeois groups. More than a hundred years have passed since then, and Gian Lorenzo Bernini ’s Rape of Proserpine continues to surprise, fascinate, and amaze generations of visitors who come from all over the world to admire the germinal masterpiece of the Baroque and the sublime genius of its author.

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.