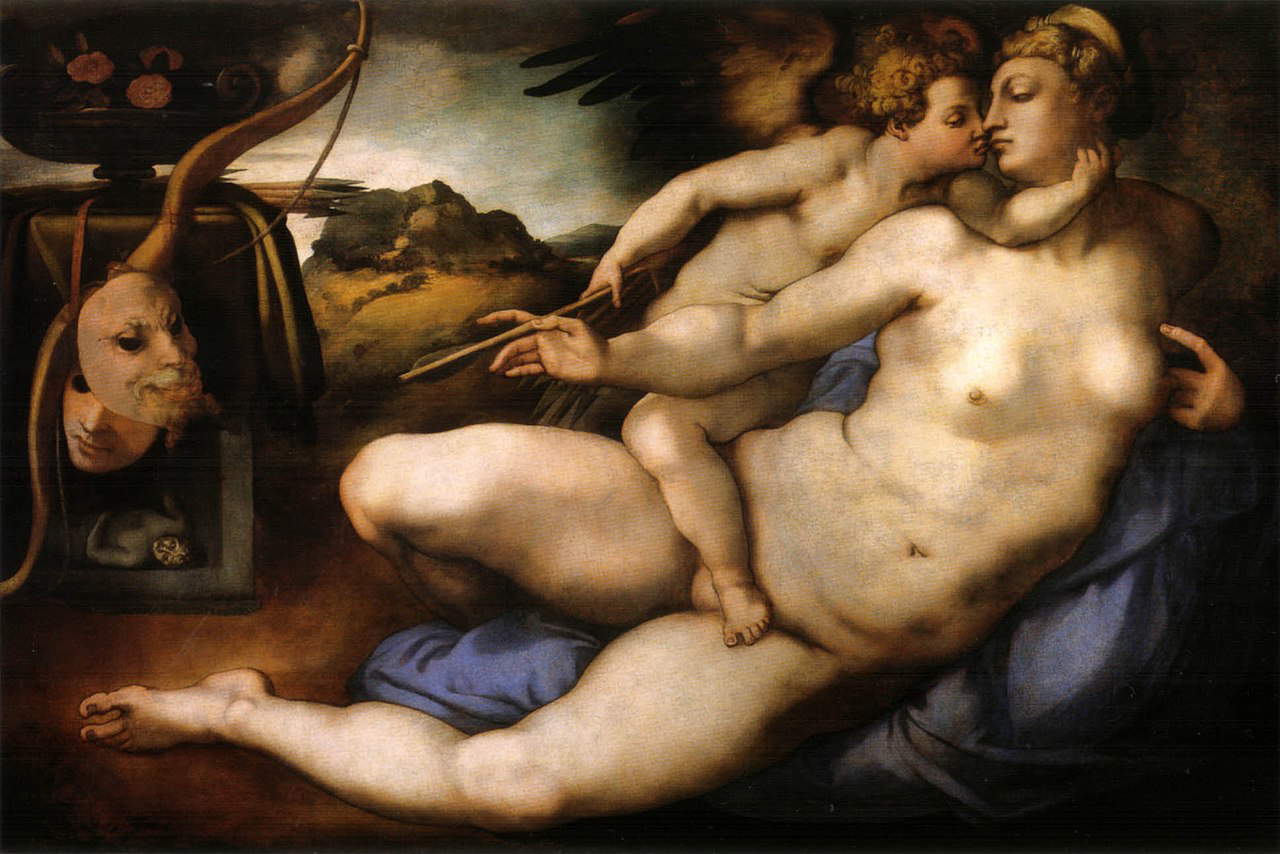

A “drama of intellectual hysteria” in which a complex tangle of symbols, formal interlocking games, ideational abstraction and chromatic abstraction add up: this is how Andrea Emiliani defined Bronzino ’sAllegory (Agnolo di Cosimo Tori; Florence, 1503 - 1572), perhaps the Florentine artist’s most famous masterpiece. The work, now in the National Gallery in London, is also one of the works that has most fascinated scholars and art historians over the centuries, because the sensuality of the two main characters, the goddess Venus and her son Cupid, the very high attention to detail as well as some rather disturbing and difficult-to-read elements, have sparked passionate discussions about the meanings the painting might conceal, and which are still not entirely clear today.

The panel was possibly painted for the King of France Francis I and was made around 1545: however, we do not know for sure who the commissioner was, and some scholars speculate that theAllegory was originally a gift from the then Duke of Florence Cosimo I for the sovereign, while according to others it may instead have been a tribute commissioned by Bartolomeo Panciatichi, a Florentine gentleman who had been educated in France, where he later also carried out diplomatic activities on behalf of the Florentine court. Both hypotheses could be well-founded, since Bronzino was a court painter in Florence during the years of Cosimo I (many of his portraits of the members of the Medici court have been preserved, such as that of Eleonora di Toledo, another of his great masterpieces, or that of Bia de’ Medici), as he was one of the most important portrait painters of the 16th century, but he was also in the service of the Panciatichi family, which was one of the most distinguished in Florence at the time: for them, too, the artist executed a number of portraits, including that of Bartholomew himself, now preserved in the Uffizi. In 1860 theAllegory was in the collection of the French collector Edmond Beaucousin, who that year, on January 27, gave forty-six of his works to the National Gallery in London, where they can still be admired today.

It is likely that Giorgio Vasari is referring to this painting when in his Lives he describes “a painting of singular beauty that was sent to King Francis in France, within which was a naked Venus with Cupid kissing her, and Pleasure on one side and Play with other Loves, and on the other side Fraude, Jealousy, and other passions of love.” However, due to some details in the description that seem to disagree with what appears in the painting itself (in fact, the “Pleasure” is missing, the “Other Loves” is missing, and the unmistakable figure of time that appears in the upper right is not mentioned), it is conceivable that Vasari was referring to another painting sent to Francis I, or that he simply did not remember the composition well: it is necessary to point out that between the making of the painting and the publication of the second edition of the Lives (the 1568 Giuntina edition, the one in which Vasari mentions painters who were still alive while he was writing, among whom was Bronzino himself), a lapse of time of about twenty years elapses, so it is entirely likely that Giorgio Vasari did not have the individual details of the composition well in mind. Again, thinking of a hypothetical commission for the French sovereign, it is true that the subject at once lascivious and erudite suited Francis I’s temperament and tastes well; on the other hand, however, it should be pointed out that there seems to be no trace of the panel in the inventories of the French royal collections.

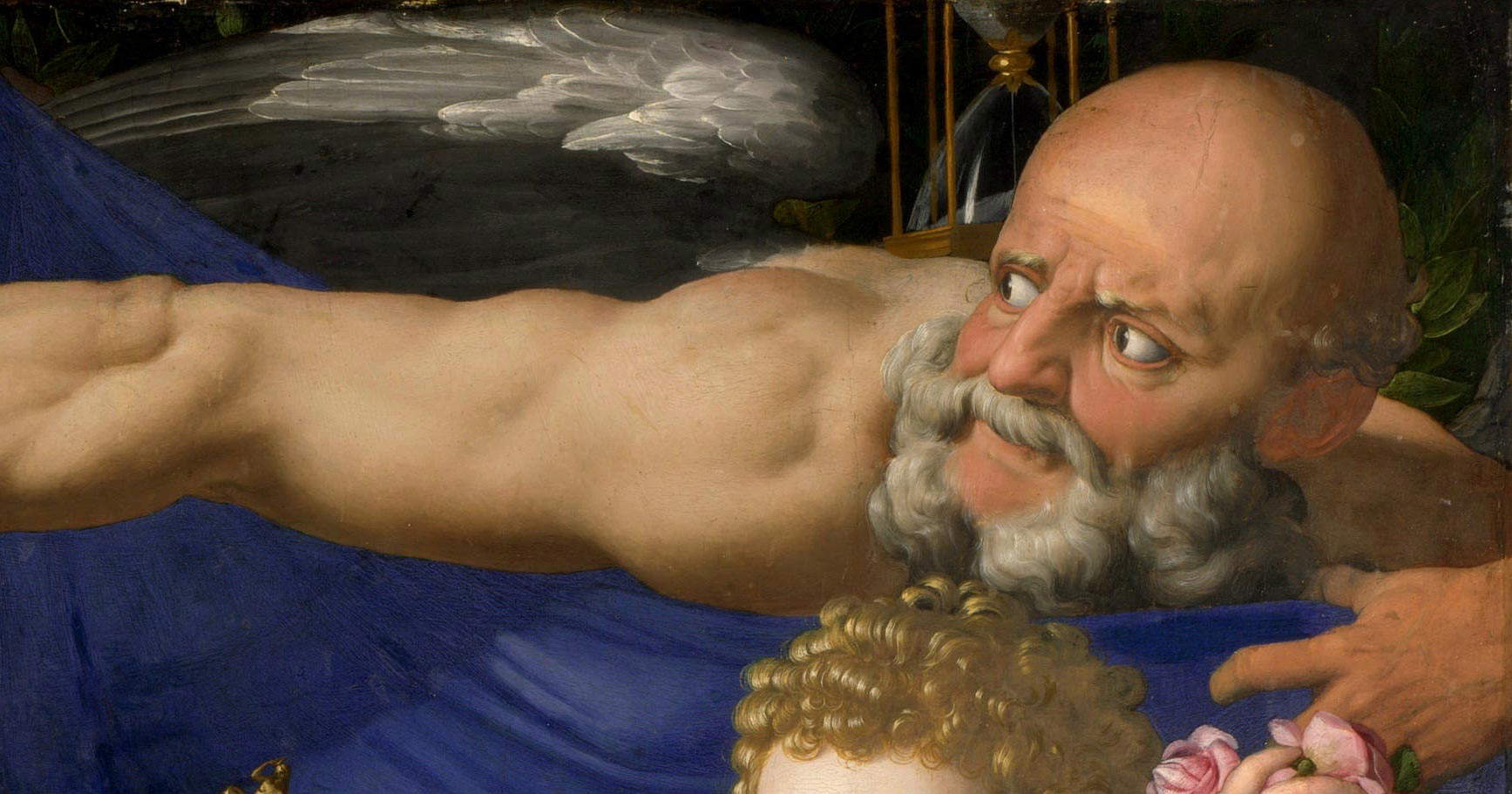

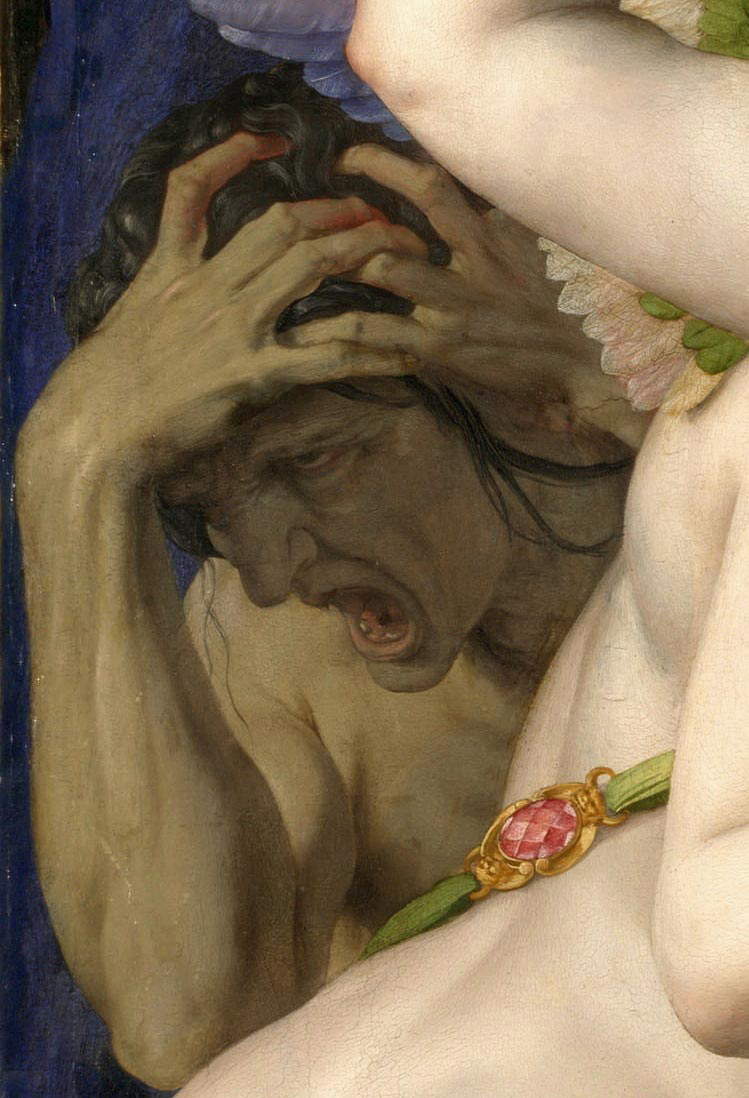

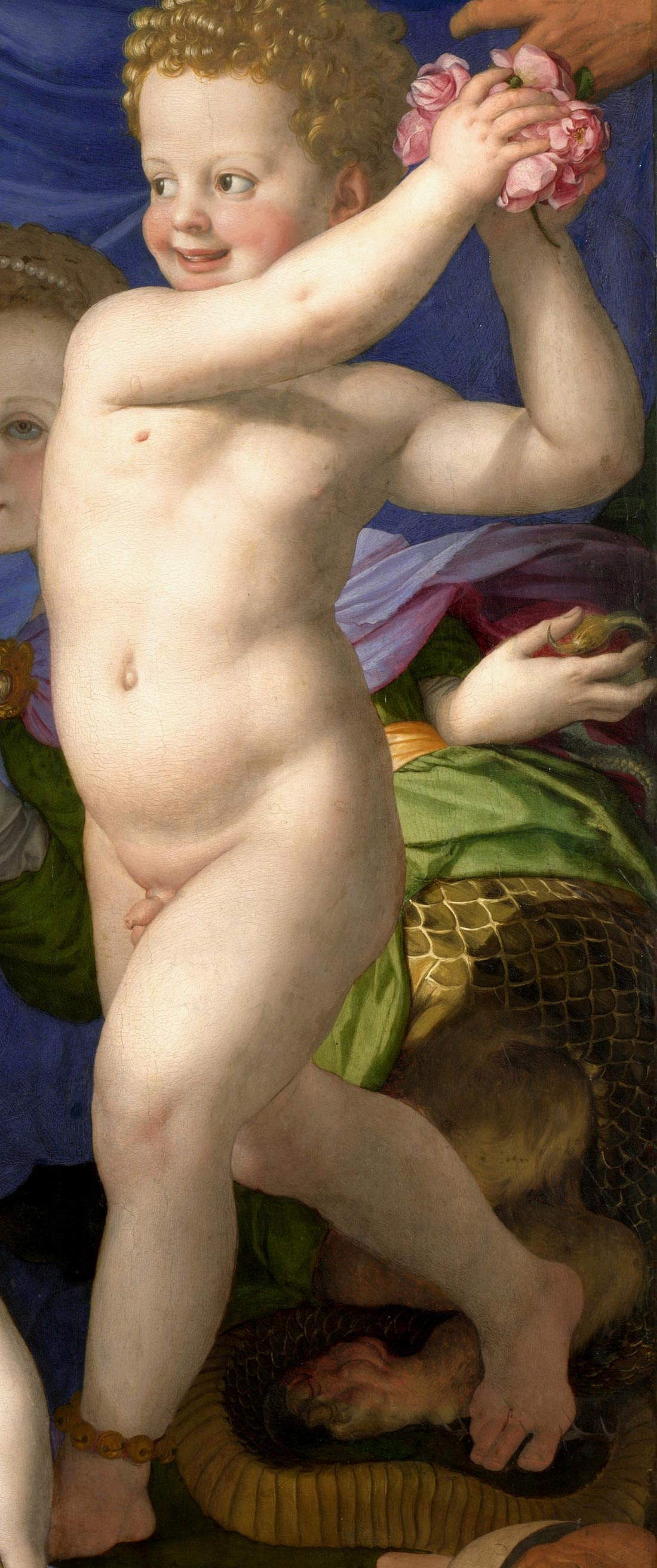

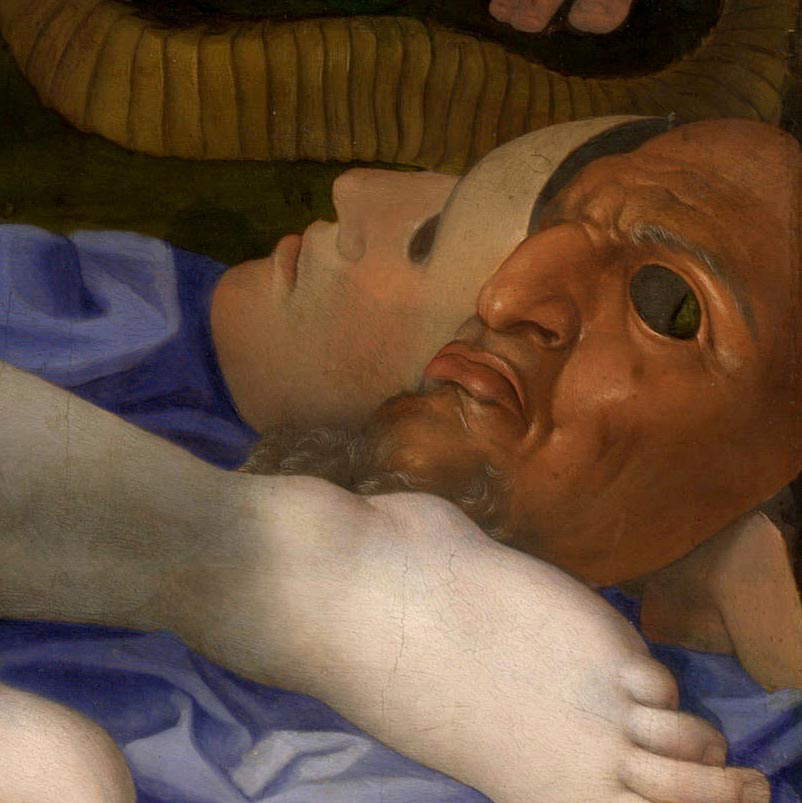

In the center of the painting are, as anticipated, Venus and Cupid, embraced as they exchange a very sensual kiss, and at their sides appears a large group of figures: one can see at the top an old man (Time) towering over the scene and whom Vasari, as mentioned, does not mention in his description, and then on the left two figures, a decidedly disturbing one caught in the act of screaming bringing his hands to his hair and another in profile holding a cloth, while on the right one can see a child holding some roses and next to him a disconcerting creature with the face of a child, the body of a snake and the paws of a lion. A series of objects and jewelry described with the highest care complete the composition.

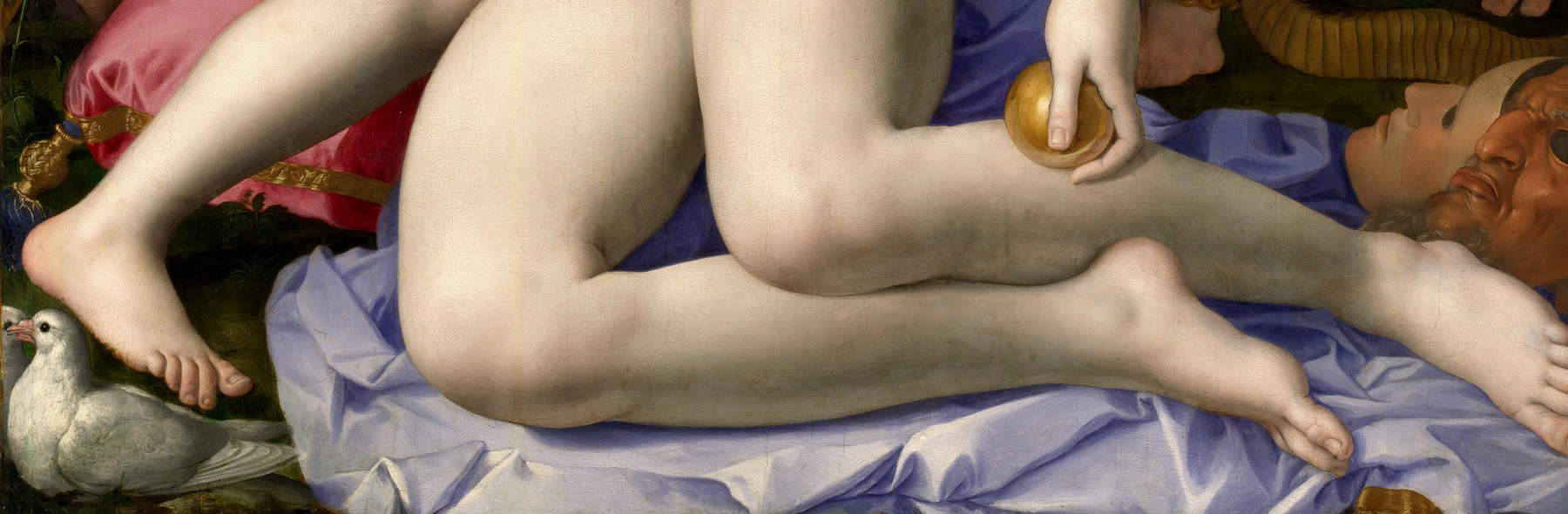

The identification of the two protagonists, Venus and Cupid, is facilitated by their attributes: the goddess holds the golden apple in her left hand, an allusion to the mythological episode of the judgment of Paris, who is said to have delivered the apple to the most beautiful of the goddesses, while in front of her she holds a dove, a symbol of love as well as a sacred animal of the goddess of love. Cupid, the son of Venus, on the other hand, is depicted as a winged child, according to typical iconography, and on his shoulders he carries a quiver inside which he guards the arrows with which he strikes lovers. The two, as mentioned, are enveloped in a sensual embrace as they exchange a passionate kiss, so much so that the viewer is able to see Venus’s tongue lapping at her son’s lips (a detail that did not escape Federico Zeri, who called this kiss as “one of the most erotic in Italian painting.” indeed, it is perhaps the first tongue kiss depicted in a painting), and in turn Cupid, with one hand, caresses the goddess’ breast. Venus is in complete nudity, and although her face is depicted in profile, her body is instead depicted in three-quarter view, and this allows the viewer to fully appreciate the sensuality of the goddess: Bronzino does not conceal any detail from the viewer’s eye.

We are in the presence, as Federico Zeri wrote again, of a painting that demonstrates to us “the merits of love, the moments of enjoyment,” but also “anxieties and unconfessed facts,” and here again we will stick in good part to the’symbolic framework discussed by Zeri in the Dietro l’immagine conversations, in which the Roman scholar provided the public with a comprehensive reading of the work, trying to mediate between all the interpretations that had hitherto been given around the meaning of the painting, which in many ways is still obscure.

There is indeed a sense of unease, something strange, that makes the viewer uneasy. And the interpretive problems already begin with the figures of Venus and Cupid. We notice that the clasp of Cupid’s quiver is decorated with a precious gem, a ruby, housed on a bezel that has two monster-shaped ends, which almost seems to be formed by two devils. This element could symbolize the baser and more animalistic sexual instincts that sometimes characterize amorous feeling, also on account of the fact that the Christian iconography of the devil finds its basis in the satyrs of Greco-Roman mythology: satyrs were in fact represented as beings connoted by a crude and exaggerated sexual appetite. Taking this detail into account, one could therefore identify in Cupid the more material aspect of love, and in Venus, on the contrary, the spiritual one: one can easily notice how the goddess is drawing an arrow from Love’s quiver, and this gesture could be interpreted as the victory of the spiritual side of love over the material one, since Venus is disarming and thus rendering Cupid helpless. Another hypothesis instead examines the gesture Cupid makes with his left hand. The son is caressing his mother, but perhaps he is also slipping the precious diadem from Venus’ head, and this element, seen in correlation with the gesture of the goddess taking away the arrow, could also allude to the deceptive nature of love: while the two are kissing, they are actually deceiving each other in that they are both stealing something (the motif of mutual theft, Robert Gaston has suggested, could be of literary origin: it appears in fact in the Sorti di Francesco Marcolini, a book printed in Venice in the 1640s). The tiara of Venus is composed of pearls symbolizing the purity of love, an emerald, a stone sacred to the goddess, and a diamond, a symbol of the strength of love but also of nobility. In his depiction of jewelry and precious objects in general, Bronzino reveals a refinement that is unparalleled and which was also revealed in all its fullness in his work as a portrait painter at the Medici court: this interest in goldsmithing on Bronzino’s part could be explained by his closeness to Benvenuto Cellini, also a Florentine. Moreover, the diadem of Venus is adorned with a female figure, perhaps precisely a depiction of the goddess of love, which closely resembles some of Cellini’s solutions: the position is reminiscent of that of a Leda that appears in a brooch by Cellini made around 1530 and preserved at the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence, but the diadem of Venus could also be related to the very famous saltcellar made between 1540 and 1543 and preserved at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. It is highly probable that Bronzino never saw this work in person, but it is instead conceivable that he saw Cellini’s drawings, and if one takes into account the fact that the saliera was also intended for Francis I as was probably theAllegory, one might find further evidence of the link between Bronzino’s art and that of Benvenuto Cellini.

The meaning of the other figures appearing in the painting is not entirely clear: the one most easily identifiable is the old man in the upper right, who is an allegory of Time, as he is endowed with the typical iconographic attributes, namely wings and an hourglass. The figure in profile, the one with the cloth in his hand, could be interpreted asOblivion, who with the collaboration of Time is spreading his veil to obscure love and to extinguish and make one forget passion. Or, Time is simply revealing the deceptions of love by trying to prevent Oblivion from hiding them. Another hypothesis, though less likely, has it that the figure in profile is theDeceiver, with half a hidden face and veil to conceal the frauds and betrayals that are often hidden behind a love affair. The horrifying screaming figure on the left has also been interpreted in several ways, including the fact that its gender is uncertain, and it is not possible to determine with certainty whether it is a male or a female figure. If female, it could symbolize Despair or Jealousy or evenEnvy; if male, however, it could symbolize the harmful effects of syphilis, a disease that was widespread at the time as well as one of the main physical ills caused in those days by love (a hypothesis, that of syphilis, to be ruled out if one imagines a destination for Francis I: a reference to the disease would have been inappropriate, if not outrageous). The child on the right might instead symbolize the Love Game or Pleasure: in his hand he holds some roses, his left leg is adorned with an anklet of rattles, and his right foot instead rests on some thorns, one of which pierces him, giving him a wound. The roses allude to amorous pleasure, the anklet to the purely childish dimension of play, while the wound emphasizes the fact that love does not care about the pains or wounds it can sometimes cause. The creepy little girl-faced monster could be symbolic ofDeception: on the surface a harmless, good-looking child who in reality hides a horrifying nature. Her hands are reversed, and this element also causes an effect of estrangement: one carries a honeycomb of honey, a symbol of the sweetness of love, while the other carries a snake, an allusion to the pain that love can cause. Another, less credited, hypothesis identifies the strange creature as Pleasure, which has a dual nature in that it causes joys symbolized by honey and a girl’s face and pains symbolized instead by the snake and monster body. Symbols of deception could then also be the two masks, one male and one female, found beside the delicate feet of Venus.

Similar motifs are found in a work similar to the one in London, the BudapestAllegory , animated probably by intentions not so different from those of the London panel, but less famous than the National Gallery masterpiece. Here, too, we in fact see Venus having taken an arrow from Love and seeming almost to converse with him. Behind we observe a vase of roses (the flower dear to the goddess), while also in the Budapest painting we again notice a monstrous figure with snakes in her hair (perhaps Envy or Jealousy), while the two putti in the foreground who are playing with a wreath of flowers still allude to play. Next to them, however, here the mask motif appears again. Curiously, on the occasion of the major Bronzino exhibition held in 2010 at Palazzo Strozzi, during the diagnostic investigations that preceded the restoration of theAllegory of Budapest, it was discovered that earlier in the painting the artist had painted a satyr in the lower portion, and the arrow was aimed at him, as if to signify Venus’s preference of carnal love in place of spiritual love. It is the same satyr found in Bronzino’s third known allegory having Venus and Cupid as its protagonist, the one in the Galleria Colonna in Rome, where the satyr again embodies the baser drives, the sexual instinct.

The

The

Returning instead to the painting in the National Gallery in London, the overall meaning could therefore imply an allegory oflove, or even anallegory of pleasure: it is not possible to say precisely. Recently Cristina Acidini has also proposed a completely different meaning than those about which there has been the longest debate, which is worth accounting for precisely because it is a particularly bold hypothesis, namely a triumph of truth: “Escaped from the pitfalls of the Fraud that has thrown off its many masks, of the mad Pleasure destined to convert into pain [...] and of the emaciated and defeated Envy that screams all its rage, who is it that can emerge naked and triumphant to the sight, if not the innocent Truth-true Innocence, for the joy of Love that seals with a kiss its liberation?”. For the doves and the apple, which in any case remain precise attributes of Venus, Acidini tries to provide her own interpretation: the doves as a symbol of whiteness (and thus innocence), and the apple always with reference to the judgment of Paris, but in this case “the most beautiful” would be, precisely, Truth. According to the scholar, identifying the woman as the personification of Truth, instead of as Venus, would dispel “the shadow of incest over that open-lipped kiss,” and the painting could also be motivated by a diplomatic action aimed at exonerating the eventual donor from slander.

Bronzino’s iconographic sources might instead be more accurate: the painting’s two beautiful protagonists might have been inspired by Michelangelo’s famous cartoon of Venus and Cupid, now unfortunately lost and known from works by artists such as Pontormo or Michele di Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio: also in Michelangelo’s cartoon the two protagonists were embracing and exchanging a kiss, but Bronzino goes further by making his figures much more sensual, partly because in Michelangelo Cupid’s foot covered Venus’ pubis, and at the same time Bronzino makes the kiss much more passionate. Another point of reference may also have been Parmigianino, and in particular his Cupid known in several variants (the most famous is probably the one preserved in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna). There are also those who have called into question Raphael’s Holy Family of Francis I , a work now in the Louvre that was sent (in this case we know for sure) to the French king by his ally Lorenzo de’ Medici, Duke of Urbino: several scholars have identified visual elements that Bronzino would take up (for example, the position of St. Joseph and that of the angel who is placing a crown of flowers on Mary’s head), and one art historian, Leatrice Mendelsohn, has read in it a kind of challenge that the Florentine artist would have addressed to the Urbino from a distance. Certainly theAllegory in the National Gallery is one of those compositions in which the artist, as Luisa Becherucci has written, reveals “a living sensuality but all filtered into acute intellectualism,” like the BudapestAllegory .

The work is also distinguished by its cool colors (the ultramarine blue of the canvas that forms the painting’s background stands out in particular), by its surface that appears glazed, by the contorted pose of the characters that follows the serpentine line typical of Mannerist art, by theartificial lighting, direct and dazzling, which minimizes the sense of depth and makes the skin of the characters glow, who appear almost sculpture-like (for Sydney Freedberg this is an effect deliberately sought to allow the painter to become a kind of Pygmalion in reverse). It is a masterpiece of that “plastic, superbly glacial idealism” of which Roberto Longhi had spoken. There is no doubt, looking at such a painting, that even if the recipient was not the king of France, he was still a patron of the highest order, who could afford such a luxurious object, or was deemed worthy of receiving it as a gift. And above all, he was able to understand the meaning of the painting, which was unquestionably intended for an elite, for a small circle of personalities who could understand the complex web of symbols, references, allusions of Bronzino’sAllegory , a work that even today remains partly obscure to us, that we cannot fully grasp, perceive in its completeness. Or perhaps that is exactly what those who elaborated the complicated allegory intended.

And then, what we can be relatively certain of, is that whoever it was intended for, surely the work had to like it, not only because it was a work of great impact, but also because it was the result of the elegant and ingenious imagination of one of the most cultured and refined artists of the time, capable of returning a masterpiece dominated by the figure of Venus that reminds everyone of the beauty and pleasantness of love. It will not be forgotten that Bronzino was also a poet, and such a sophisticated painting, besides being typical of the culture of the time, also reveals the intellectual bearing of an artist in whose writings it is not uncommon to find references to the ambiguity and duplicity of love. Take for example this sonnet: “D’amor puro, e di fede, e pura voglia / Onesti giochi, e senza fallo, o menda / Già non par da biasmar, perch’uom si prenda, / E de’ gravi pensier la cura scioglia. / But this new one, ov’ognor pare, that welcomes / Bellezza Amore, and ’l chiaro lume accendere, / Tem’io, che tanto cresca, e tanto splendenda, / Che di troppo piacer li nasca doglia. / The time is not so far to come / Of their highest degree, nor you so frank, / That you may not yet burn many, and many years. / Close to repentance the entrance now, that thou hast time, / Nor then do thou sigh in vain the best, and to the side / Pass the ardor, that already blazes thy clothes.” Perhaps the work is not wholly due to Bronzino, who, however learned he might have been, almost certainly worked from a program drawn up by a scholar at the court of Cosimo I. It is clear, however, that in Bronzino’s art there is a lively correspondence between images and words, and it cannot be ruled out, therefore, that theAllegory in the National Gallery may also have been inspired by some poetic image of the artist’s, or that among the artist’s sonnets there is some lyric to be interpreted as a refined commentary on the painting.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.