Seemingly off the main routes, there are places that more than others, due to a close conjuncture of events, fully embody the “spirit of the times”: in German, Zeitgeist is a sublime word that sums up the values and spirit that inform an era. Places that welcome and give rise to revolutionary ideas, that gather within their boundaries “unclassifiable” characters somewhere between dissidents and outsiders but also extraordinary women. These are places, these, where initially exceptional experiences arise that over time become commonplace, habits. Sometimes, the zeitgeist can best manifest and express itself in places that for years, and for more than one reason, either charted an unprecedented course or marked a change of course. One such place, whose events between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries are, as we shall see, to be rewritten, is Canton Ticino.

The southernmost region of Switzerland, the canton where Italian is spoken, because of the number and nature of the events that took place here, has been the place where the writer has seen fit to question certain certain certainties and information considered valid until recently. The history of Switzerland in those years needs to be revised. And perhaps, that ofabstract art as well.

That the town of Ascona, on the shores of Lake Maggiore, constituted an ingenious laboratory of ideas, was already partly known. What emerges from the advancement of studies (and, as a result, a clearer picture also emerges) is that Ascona represented the incunabulum of a new avant-garde in the fields of art, philosophy, religion, and mind studies: in a word, a cultural neo-avant-garde, moreover, in such difficult years as those experienced before and during the two world wars.

So if up to now, therefore, we have been talking about the south as the starting point for the Monte Verità affair (a reality that, with a rather rapid process, was first established as a vegetarian colony, and then transformed into an international hothouse of artists and scholars), now the research cannot but invest the whole territory around that great, exceptional experience, whose baptismal year must be traced back to 1889.

In that year, the area of Monte Verità was purchased by the president of the Theosophical Lodge of Milan, Alfredo Pioda, who wanted to make it a secular monastery, “Fraternitas,” but from there shortly thereafter, in the early twentieth century, thanks to Ida Hofmann and Henri Oedenkoven, Lotte Hattemer, Ferdinand Brune and the eccentric anarchist (later captured, interned and placed under guardianship1) Karl Gräser (who for living in a cave would inspire Herman Hesse’s novel Siddhartha), Monte Verità, in order to counter the prevailing capitalism and rapid industrialization, would become a meeting point for a “vegetablian” colony, an entirely out-of-the-ordinary community that experimented and allowed its members to live in complete freedom (in the open air and in “air-light” huts), beyond all political, religious, “moral” restrictions, practicing nudism and free love.

Also here, in 1913 came Rudolf von Laban who “in the wake of the widespread ideas of ’synthesis of the arts’ (Gesamtkunstwerk), ”2 thus anticipating the same experience as Gropius’s early Bauhaus of 1919, set up his dance school there, later also attracting the interest of IsadoraDuncan. In 1925, it was the turn of artists such as Sophie Tauber and MargueriteHagenbach with Hans Arp. The foundation that bears their name is still located in this area, includes the famous “clouds,” and the garden sees Arp’s biomorphic works Femme paysage and Fruit de la lune installed. The environment is frequented by Moholy-Nagy, and it is important to note that Marguerite is also credited with playing no small role in the entry of abstract art into Switzerland.

|

| View of Ascona. Ph. Credit Switzerland Tourism |

|

| The colony of Monte Verità in Ascona |

|

| The village of Monte Verità, now a museum route. Ph. Credit Switzerland Tourism |

|

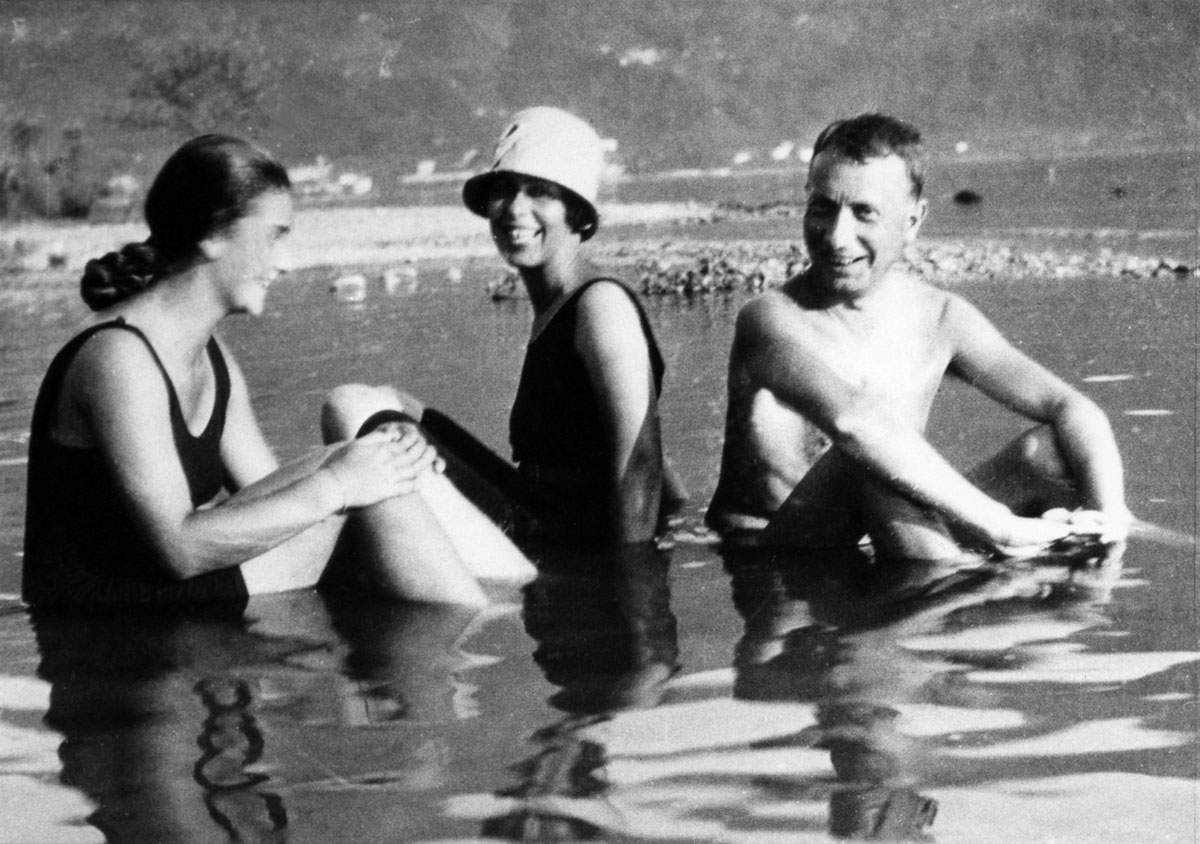

| Elisabeth Wiegmann, Sophie Taeuber and Jean Arp in Ascona in 1925. |

|

| Hans Arp’s house in Ronco dei Fiori. Ph. Credit Roberto Pellegrini |

|

| Arp with the work Fruit de la lune in the house in Ronco dei Fiori |

The annusmirabilis of Monte Verità is 1926, because of the purchase of the area by Baron Eduard von der Heydt and his wife Vera, and because of what will arise from this episode. From that year on, Ticino will represent the tip of the iceberg of a submerged world, becoming, yes, also a tourist destination for travelers from all over Europe, but first and foremost it will open up to the future, when it will welcome the extravagant ideas and curatorial “obsessions” of HaraldSzeemann, a leading “chaotic and orderly” (Soldini) figure on the contemporary art scene, active in Ascona until the 1980s.

Ticino’s is a long and fascinating parabola that, starting in 1933, also embraced another extraordinary cultural initiative: despite the complex political climate and the scarce means at its disposal,3 the Eranos Foundation, an occasion for interdisciplinary dialogue, to be considered in those difficult years a pioneering phenomenon in Europe, started its activity here. The presence of CarlGustavJung, who arrived here in 1938 and remained until 1946, embellished and animated the meetings, because his studies, which unveiled the existence of the “collective unconscious” and which explored the realm of myths, symbols, and images of an archaic humanity, had an impact on the global cultural world and also on the work of an artist who arrived in Ascona in 1954, Luigi Pericle.

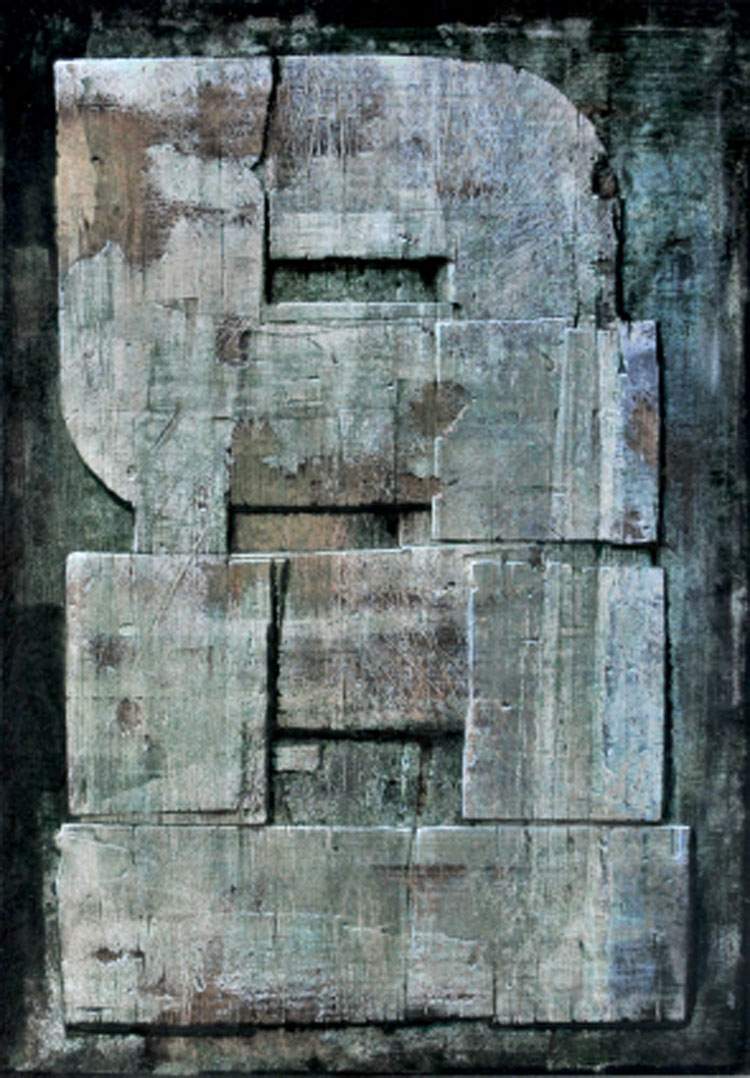

An out-of-the-ordinary character, an all-round artist, Pericles is a 20th-century “philosophe,” who came back to light two years ago, in 2018, thanks to the purchase of his mansion by Andrea and Greta Biasca-Caroni. We know for certain, from the documents that have come down and are kept in the Archives, that Pericles lived in Ticino during that historical phase in which the certainties of knowledge and science are being partly unhinged and put under the scrutiny of new studies. Ticino is in full ferment: when Pericles arrives there he not only finds his proper dimension, but in the light of the events that occurred in those years and that these studies are highlighting, his painting, from figurative, evolves in a more abstract-informal sense with a language made of symbols, tracing the terms and premises of that “imaginary unexplored world” that, a few kilometers from Ascona, Jung was revealing.

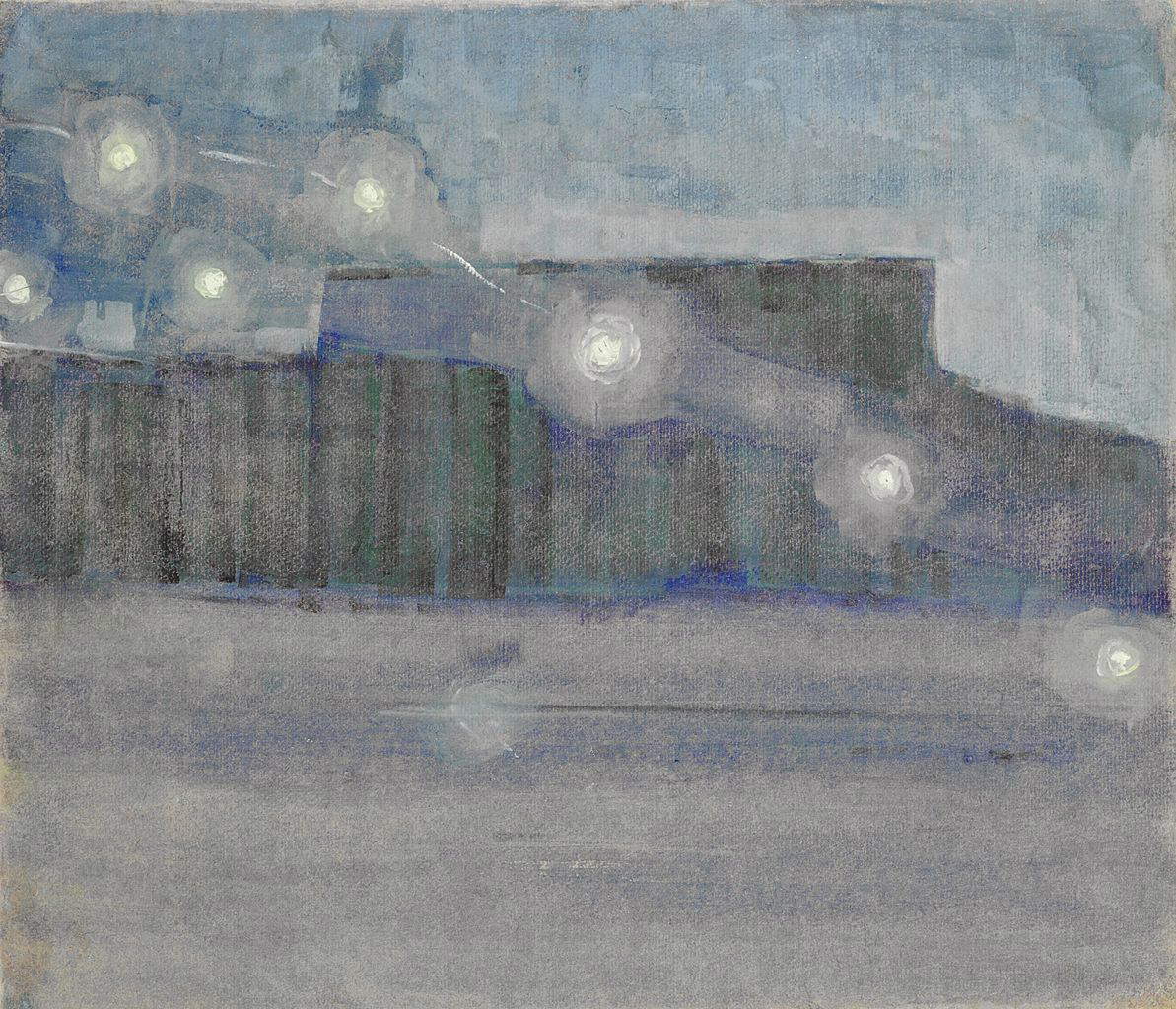

The energies that this land releases, the innovative instances that it has been able to graft, have been many, and it is legitimate to frame in the economy of this discourse also the name of Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, a painter who, as an exhibition held at the Palazzo Reale in Milan a few years ago showed, anticipated and anticipated abstract art. The Lithuanian artist introduced it as a line of rupture in the circle of ideas well before the first abstract watercolor (1910) by VasilyKandinsky, from which it has hitherto been derived. The painting of Čiurlionis was already known before that date, since he had participated in very relevant exhibitions such as those in Moscow in 1911-12, St. Petersburg and London in 19124.

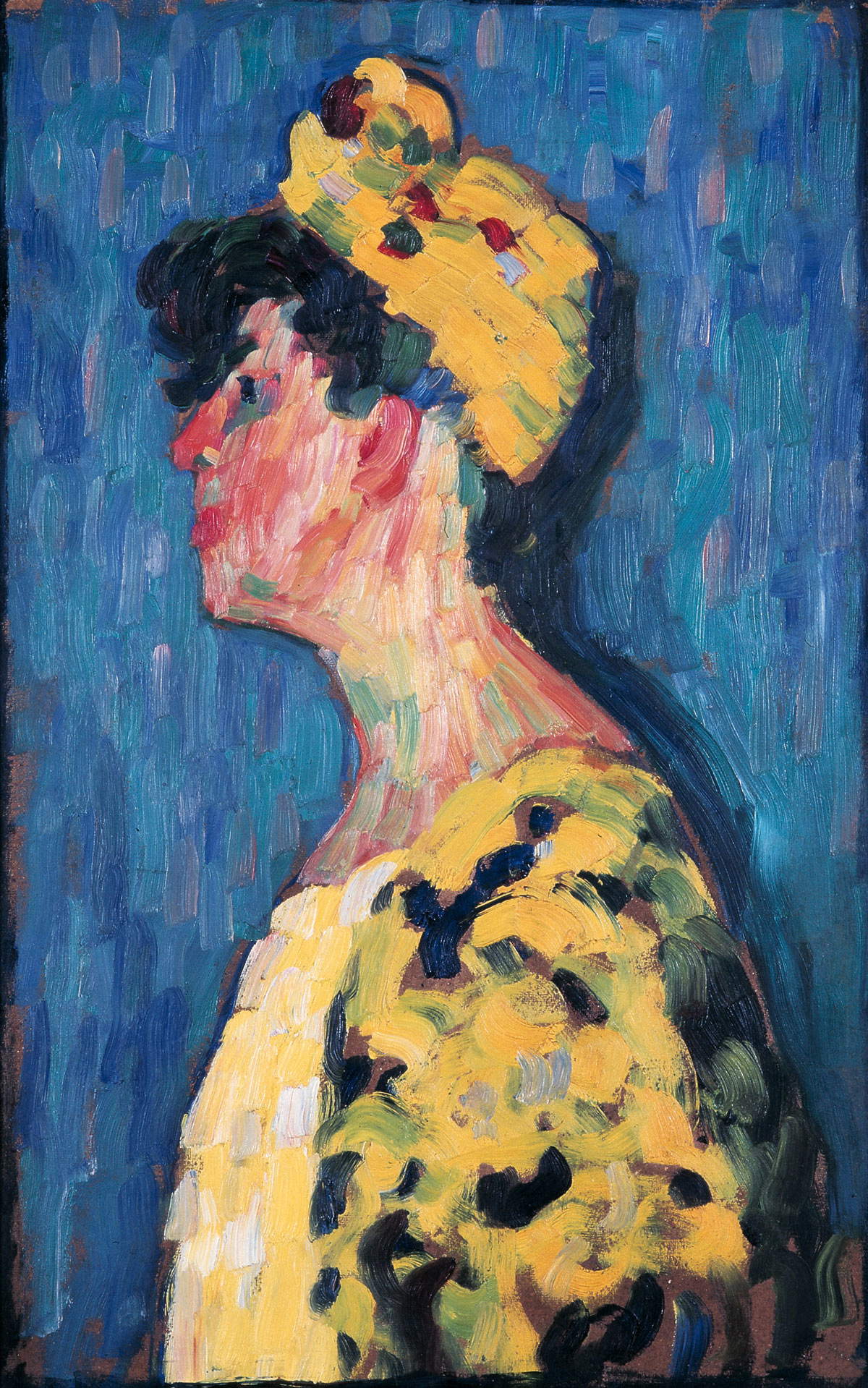

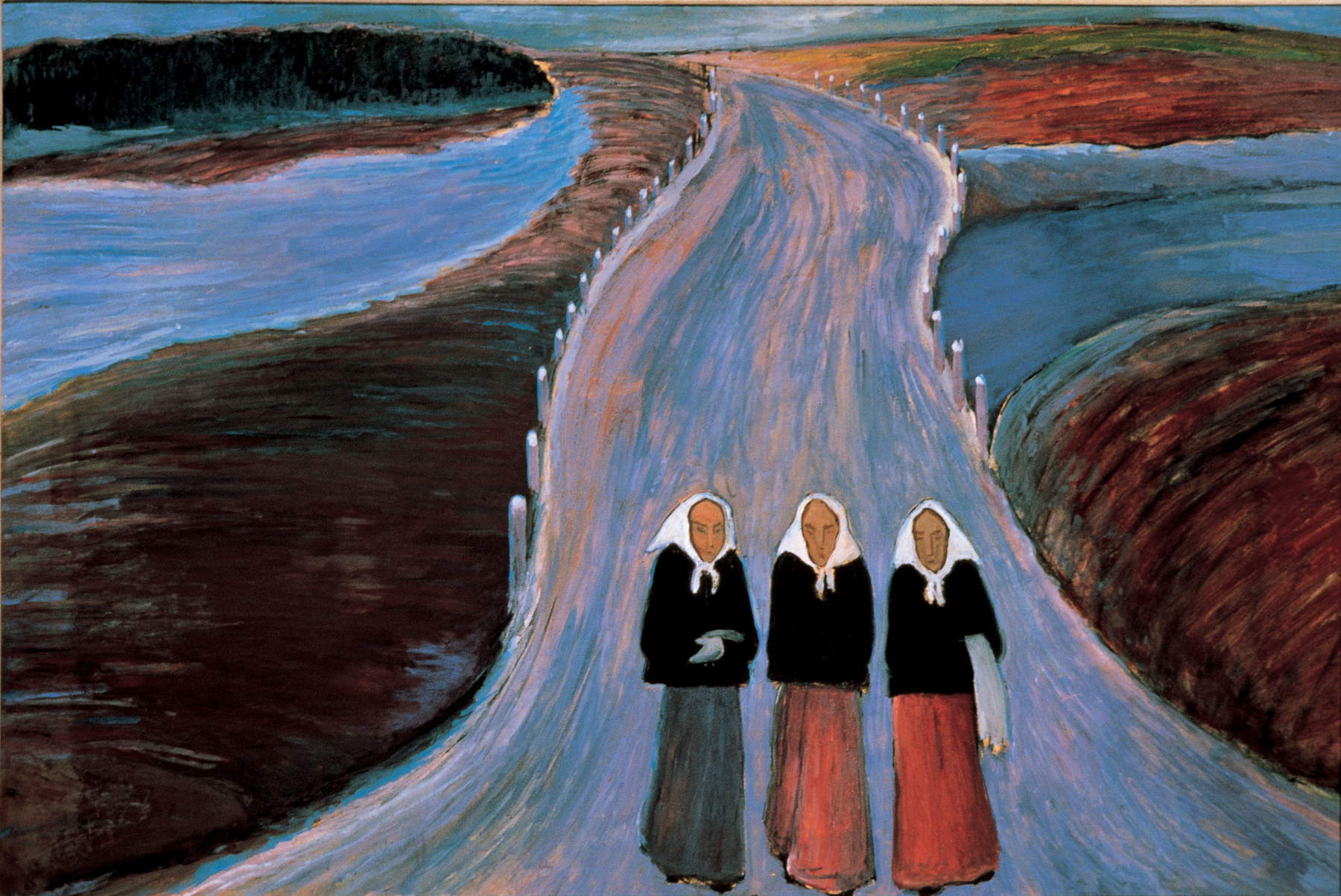

It is exceptional, however, how this same artistic expression, paradoxically in the same years, was not the favorite path of the Russian painter (active in Ascona) MariannevonWerefkin, because, unlike her companion, also anhimself an artist, Alexej von Jawlensky, it was considered by her to be too elitist and not accessible to all, and this is the case even though she herself invited Čiurlionis to Ascona and contributed to the spread of abstract art in Ticino before Kandinsky took on the role of spokesperson.

|

| A meeting of the Eranos group |

|

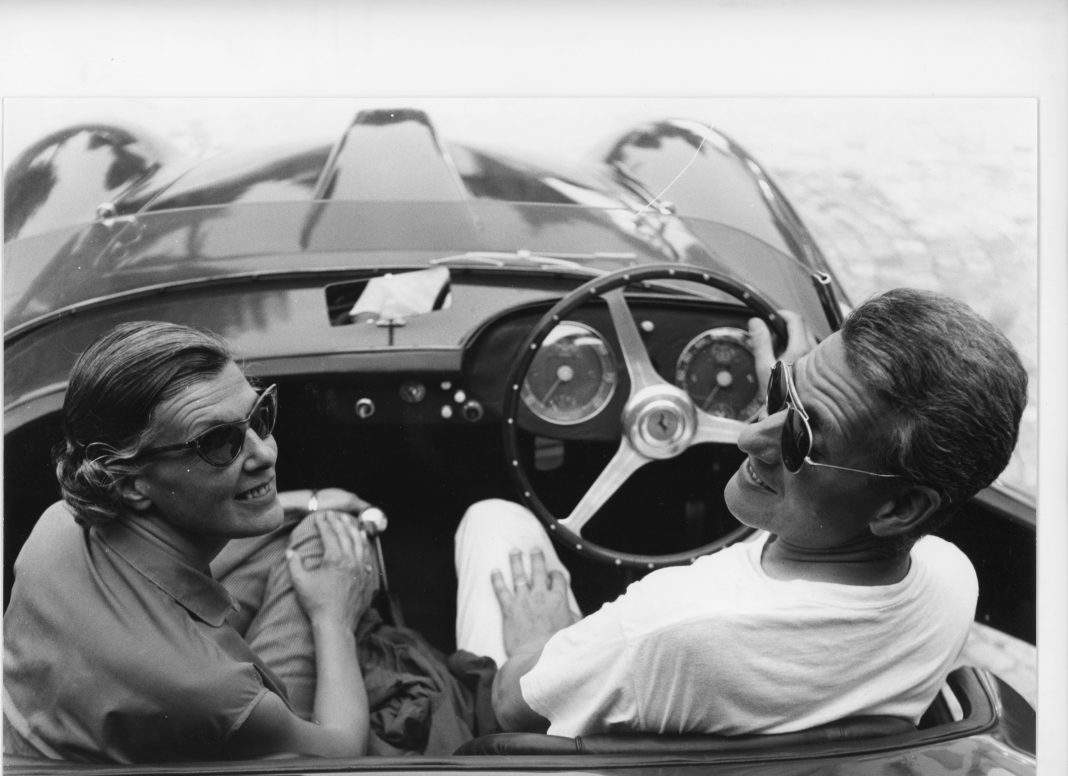

| Luigi Pericle with his wife Orsolina in the artist’s Ferrari |

|

| Alexej von Jawlensky, Portrait of Marianne Werefkin (ca. 1905; oil on cardboard, 71 x 45 cm; Ascona, Municipal Collection of Ascona, Museo Comunale dArte Moderna) |

Demonstrating how nothing in Switzerland was taken for granted, and no absolute truths or novelties were accepted without question, Werefkin therefore did not allow herself to be enchanted by this artistic avant-garde, not even by the most up-to-date ones, whether born in Switzerland or arriving from outside. Every topic had to be recalibrated, even in the religious sphere, and in those of science, mind or art. So much so that even Pericles entered the discussion on abstraction even by means of the vademecum Instructions for Practice - for dealing with the painter L.P., which he wrote, and which accompanied the tour of his works, where the artist points out, “All great art is abstract. The fact that the layman cannot see in figurative painting abstraction in color, form and structure certainly does not invalidate this assumption.”

There is another point to be made, however: if it is true that the veracity of any known information had to be reconsidered and that any ancient or unpublished manifestation was something to be questioned about, it remains to be clarified to what factors in particular this “ambitious” mode of operation can be attributed. It is necessary to look at a broader horizon and ask whether the Swiss territory, which during the bloodiest years of world history opted for a political choice different from other nations, finds in its “neutral” character the reason for the evolution of such a convergence of events and significant experiences. Is it a plausible hypothesis that this factor played such a decisive role in the development of so much cultural richness?

And above all, what was the impact of the evidence that Ticino was the place where the Ascona-Locarno agreements were signed on October 16, 1925, and where Operation Sunrise was christened (exactly at Via Signore in Croce, close to the Archives and next to the hill of Monte Verità)?

If it was a strategic meeting point (for “depth psychologists, orientalists and ethnologists interested in the history of religions to meet and collaborate ”5) how did these subjects, which, as’is well known, involve the encounter and confrontation with an unknown, foreign and even ’dangerous’ world, likely to threaten the spiritual balance of the modern West?

And again: how did these elements affect, even in view of the fact that a political balance, in convergence of the outbreak of the two world wars, was impossible to maintain? Not only the wars and the devastation they entail, but in the face of the publication of Sigmund Freud’s discoveries, which, in those years, allowed a further opening to the submerged worlds of the unconscious, even consequences such as the loss of meaning and the bewilderment of consciousness were probably inevitable.

|

| Luigi Pericle, Matri Dei d.d.d. (1978; mixed media on masonite, 42 x 30 cm) |

|

| Luigi Pericle, Matri Dei d.d.d. (1963; ink on pulverized silk paper, 42 x 60 cm) |

|

| Louis Pericles, The March of Time X (1963; mixed media on canvas, 51 x 65 cm) |

|

| Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, Sparks II (1906; oil on canvas; Kaunas, Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis Museum) |

|

| Marianne Werefkin, The Country Road (1907; tempera on paper pasted on cardboard, 69 x 105 cm; Ascona, Marianne Werefkin Foundation, Museo Comunale dArte Moderna) |

|

| Marianne Werefkin, Tragic Atmosphere (1910; tempera on paper pasted on cardboard, 46.8 x 58.2 cm; Ascona, Fondation Marianne Werefkin, Museo Comunale dArte Moderna) |

Moreover, Jung’s theories undoubtedly had considerable weight, considering that the Swiss-born psychologist unveiled, with the theory of the “collective unconscious,” the existence of another world through the exploration of those hidden treasures that are the myths, symbols, and archetypes of a more distant humanity.

So in Ticino’s reality at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, underlying the formulation of the “Spirit of Time,” there was a perfect interlocking of multiple tesserae, even of communication (think of the openings of the St. Gotthard Tunnel in 1881 and the Simplon Tunnel in 1906) or, as Baxandall puts it, these ideas, helped to forge “the eye of the period,” that specific way, which belongs to all historical epochs, of understanding, processing and enjoying art.

The years of Louis Pericles, the main subject of our investigation, therefore, are the same as those of Eranos, Jung, Freud, the discussion of abstract art, and the researches of psychologists, ethnologists and Orientalists that have highlighted the human interest and spiritual value of many symbols, myths, divine figures and mixed techniques, both among Europeans and Asians and among “primitives.”

It is no coincidence that Mircea Eliade, a noted historian of religions who gravitated to Ticino for a long time, wrote in those years, “Western man [and woman] will not [be able] to live forever separat[ed] from an important part of [their] selves, that [part] consists of fragments of a spiritual history whose meaning and message they are incapable of deciphering.”

Luigi Pericle’s artistic parable hinges on this economy of rereading Ticino’s history, for that search for individuation of meaning, which Pericle honed through an encyclopedic aptitude for studies. Louis Pericles is a man out of time that, thanks to the rediscovery of the Biasca-Caroni, time has restored. But he is also a man, an artist within his own time, and can stand as a pivot point for the development of that pleonasm of experience that, we have seen, Ticino represented in those years: a place where the destinies of European culture crossed.

There is also Ascona and Ticino then, not only Paris, London or New York on the horizon of history and art. Although these are the years in which there was a relevant shift in the artistic center of gravity from Europe to the U.S., with New York in particular becoming the main city of art and the market thanks to the premises anticipated by the Armory Show of 1913, this investigation is bringing to light a more articulated reality that cannot disregard the Ticino sphere. Beyond then New York and before Zurich with the birth of Dada, Switzerland and the Canton of Ticino played an equally important role in the development of another artistic and cultural avant-garde, not to mention the contribution of Theosophy. It is therefore necessary to reopen the archives, dust off the papers, and insert another chapter in the history of art and thought. That of Ascona and Ticino.

Notes

1. M. Folini, The Monte Verità of Ascona, SSAS Swiss Monuments Guides, Bern, 1998.

2. 1922. Edited by M. Folini, V. Provenzale, M- Zucconi-Poncini, The origins of the collection. Municipal Museum of Modern Art Ascona.

3. F. Merlini, Eranos: a space and time for thought, in MEETINGS IN ASCONA, 1960.

4. M.K. Čiurlionis and Marianne von Werefkin: their paths and watersheds in LITUANUS, Lithuanian Quarterly Journal of arts and Sciences , Vol. 49, No. 4 - Winter 2003.

5. M. Eliade, Meetings in Ascona, October 1960, p. 17.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.