A document from 1602, referring to a painting by Caravaggio (Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610), informs us that the great Lombard painter had received “from Ill.re sr. Ottavio Costa a bon conto d’un quadro ch’io dipingo gli venti schudi di moneta this dì 21 maggio 1602.” It has never been known for sure what the “painting” mentioned in the note was, however, but since a 1639 inventory of the Genoese banker Ottavio Costa’s possessions lists, among others, a painting by Caravaggio depicting a St. John the Baptist in the desert, it was thought that the subject of the contract was the work now housed at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City (precisely, the St. John the Baptist). Against this hypothesis, however, has come a recent study, proposed by Caravaggist Michele Cuppone, which finds parallels in parallel studies by Gianni Papi and Rossella Vodret and which has already received the endorsement of Nicola Spinosa and Clovis Whitfield, and which was presented at a conference on Caravaggio(Caravaggio and His Own) held last month in Monte Santa Maria Tiberina (the proceedings will be published next year). According to Cuppone’s study, the painting referred to in the document would actually be the Judith in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica at Palazzo Barberini in Rome.

|

| Caravaggio, Judith and Holofernes (1602?; oil on canvas, 145 x 195 cm; Rome, Palazzo Barberini, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica) |

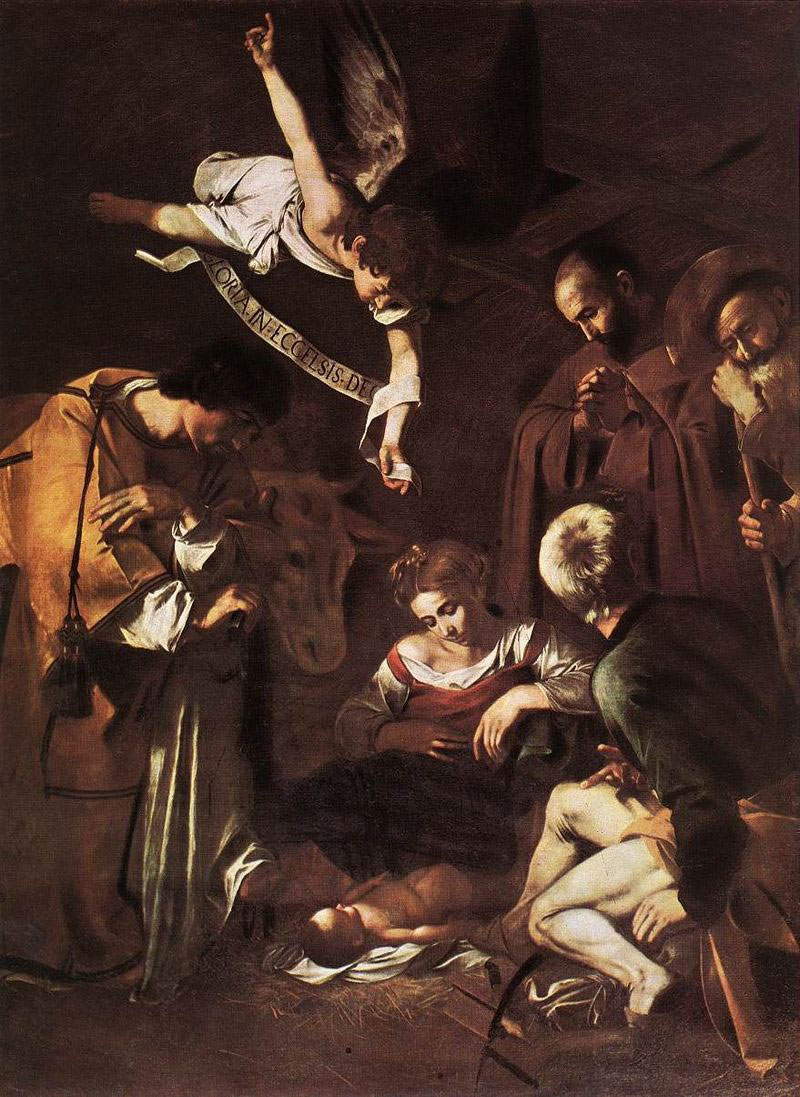

How was such a conclusion reached? An earlier study by Cuppone himself had anticipated the dating of Caravaggio’s famous Nativity once kept at theOratory of San Lorenzo in Palermo, then stolen and now considered lost. No longer a 1609 painting, as had been believed: too many stylistic differences from paintings of the Sicilian period to think that the Nativity was also painted in the last years of Michelangelo Merisi’s career. Conversely, the scholar found similarities with paintings from the early seventeenth century, for example those made for the Contarelli Chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome. A couple of examples, such as the pose of St. Lawrence resembling that of the young man at the head of the table in The Calling of St. Matthew and that of St. Joseph being identical to that of the soldier appearing in the chapel’s vault frescoed by Cavalier d’Arpino, seem to endorse the hypothesis. These similarities, a starting point to which stylistic, diagnostic and, above all, documentary evidence was added, led Cuppone to backdate the Palermo Nativity to the 1600s, that is, to the period when the paintings for the Contarelli Chapel, which date from 1599-1602, were made.

|

| Caravaggio, Nativity (1600?; oil on canvas, 298 x 197 cm; formerly in Palermo, Oratory of San Lorenzo. Then stolen and now believed lost) |

Well: if one looks at the faces of the Virgin in the Palermo Nativity and the Judith in Palazzo Barberini, one can easily see that the model who posed for the paintings is the same. All the features match: the angularity of the nose, the cut of the eyes, the shape of the forehead. Even the hairstyle is completely identical. The point, however, is that the use of light, in the Roman Judith, appears much more skillful than in the Nativity. The transitions are more gradual, the light shapes the forms of the characters better, and the luministic effects glimpsed on certain details appear more studied. It should also not be forgotten that the great drama of Judith is unparalleled in the paintings Caravaggio made between 1599 (the year to which Judith was previously referred) and 1602, the year in which the artist finished the Contarelli Chapel cycle by painting St. Matthew and the Angel. Thus moving the dating of the Judith later in time, it seems reasonable to assume that the John the Baptist of Kansas City, a more mature painting datable to about 1604 (it was thought, on the basis of the document attesting to the receipt of a down payment for the painting destined for Ottavio Costa, that Michelangelo Merisi had finished the work at a later date) is not the “painting” referred to in the document, in which instead the Judith, also anciently in the Costa collection, would be mentioned.

|

| The face of the Judith in Rome and that of the Madonna in the Nativity in Palermo. |

These are details that apparently might seem to be details of academic matters, matter for scholars that could hardly find a place on a site devoted to popularization. And of course these are hypotheses that will have to be subjected to the scrutiny of the scientific community. But in reality there is a need to emphasize how the new studies serve to re-establish a correct chronology of Caravaggio’s production, with all that this entails (opening up new points of view on paintings that have already been studied, more coherent framing of the various phases of Caravaggio’s career and, of course, of his art, more precise information in view of the organization of new exhibitions, and so on). And then, Michele Cuppone’s remarks tie in with a stringently topical fact, namely the debate over the attribution of the Judith recently found in Toulouse and which some would like to ascribe to the hand of Caravaggio. Cuppone’s study discusses how the later dating of the Judith painted for Ottavio Costa may better explain the relationship with the lost Judith that Caravaggio painted in Naples and whose iconography is not known except thanks to a couple of paintings that critics have mostly identified as copies of the Caravaggio original: one, owned by Intesa-San Paolo, is kept in Naples at Palazzo Zevallos, and the other is the Toulouse painting mentioned above.

|

| Attributed to Caravaggio or Louis Finson, Judith and Holofernes (1606-1607; oil on canvas, 144 x 173.5 cm; Toulouse, Private Collection) |

If the work in Palazzo Zevallos has by now been “degraded” by most critics to a copy made by a modest anonymous painter (and not, as was believed, by the hand of the Flemish Louis Finson, who produced works of a much higher level than the Neapolitan one), the discussion about the Toulouse Judith is as heated as ever, especially after the exhibition Attorno a Caravaggio opened in Milan, at the Pinacoteca di Brera, in which the work is even displayed with attribution to the same master, to Caravaggio. The main proponent of the attribution to Caravaggio is the scholar (as well as curator of the Milan exhibition) Nicola Spinosa, who bases his convictions on the quality of certain details that appear in the painting such as, we quote from the catalog essay, “the detail, of the highest effect in highlighting and heightening the fiery atmosphere surrounding the terrifying depiction of the violent death of Holofernes, of the red curtain sumptuously knotted in the upper left-hand corner,” or “the very high treatment of the ’half-figure’ of Holofernes, not unlike a Hellenistic deta sculpture in vigor of modeling, which, while replicating in appearance the one painted in the Palazzo Barberini version [...] is, by drafts and tones of color, of an even more touching immediacy and truth,” and again “the rendering of the features of the face of Holofernes, distraught, screaming, but now also enraged like a beast wounded to death.” There are, however, passages of inferior quality (such as the face of Judith’s handmaiden, and especially the right hand of the biblical heroine), but in essence Spinosa (who, moreover, accepts the hypothesis of the 1602 dating of the Roman Judith ) concludes by saying that “by quality indicated” it is difficult to think that it is, as many want, a copy made by Louis Finson.

The discussion about the French painting (it is certainly a work of great quality: it is worth pointing out) will presumably go on for quite some time, and it has already sparked a controversy in the milieu. Suffice it to say that the scholar Giovanni Agosti has resigned from the Pinacoteca di Brera’s scientific committee, in controversy with the decision to exhibit the work with the attribution to Caravaggio, albeit alongside a note stating that it is “a condition of the loan and does not necessarily reflect the official position of either the Pinacoteca di Brera or its board, advisory committee, director or staff.” Net of these controversies, which we have presented only to give the reader an account of how much the issue is felt, there is no doubt that the latest contributions on Caravaggio presented here, that of Michele Cuppone and that of Nicola Spinosa, are of great interest and will not fail to cause discussion in the coming months.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.