Among the few portraits executed by Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi; Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610), one of the most interesting is a nearly two-meter-high canvas in the Louvre depicting Alof de Wignacourt (Flanders, 1547 - Valletta, 1622), Grand Master of the Order of the Knights of Malta from 1601 to 1622: in the painting, Wignacourt is portrayed in his armor, standing with a page beside him who is handing him a helmet. This seems to be the first work made by the Lombard painter during his brief stay in Malta, and it is probably (although we are not certain) the painting that the painter (and Caravaggio’s great rival) Giovanni Baglione (Rome, 1566/1568 - 1643) quickly mentions in his Lives of painters, sculptors and architects published in Rome in 1642, where the artist, speaking of Caravaggio, writes that “poscia andossene a Malta, e introdotto a far reverenza al Gran Maestro, fecegli il ritratto; whence that prince in token of merit, of the habit of St. John gave him a present, and created him Knight of Grace.” However, since Giovan Pietro Bellori, in his Lives, mentions two portraits of Wignacourt done by Caravaggio, we are not certain that this is indeed the one. In any case, it is certain that Michelangelo Merisi had to depict Alof de Wignacourt “standing armed,” as Bellori wrote, which also confirmed the report that the Grand Master “gave him as a prize the Cross,” i.e., the Order’s habit, making him a knight of Malta. The painting ended up in France as it was probably brought there by Alof de Wignacourt himself: the portrait, in which the Grand Master appears in an official pose, with the staff of command in his hands, marks the beginning of one of the most interesting episodes in early 17th-century art, since the relationship between Caravaggio and Alof de Wignacourt was very close, if short-lived. Moreover, this collaboration was to be followed up in the late seventeenth century when Mattia Preti (Taverna, 1613 - Valletta, 1699) was entrusted with the further embellishment of what Wignacourt had built more than seventy years earlier.

Alof de Wignacourt, born in Flanders but of French ancestry, had joined the Order of the Knights of Malta in 1564 and, at just 18 years of age, the following year distinguished himself in the Great Siege of Malta, one of the most famous of the historical events surrounding the Mediterranean island, namely the important victory that the knights aided by a number of European powers, brought back over the Ottomans, who besieged the island in order to seize it and make it an outpost to expand into the western Mediterranean (the siege lasted four months, at the end of which the knights, who defended themselves strenuously, succeeded in driving off the Turks, causing the enemy army heavy losses). Wignacourt had become Grand Master in 1601, following the complex elective mechanism that governed the Order’s highest office: after the demise of the previous Grand Master (in fact, the office lasted for life), the members of the Order’s eight Langues (i.e., the eight territorial entities that constituted it, identified according to their languages: Italy, France, Provence, Auvergne, Aragon, England, Alemagna and Castile) chose three representatives, who would form an assembly of twenty-four members for the purpose of appointing the president of the conclave from which the name of the new Grand Master would arise, and the so-called triumvirate, composed of a “cavalier of the electione,” a “capellan of the electione,” and a “servant-at-arms of the electione.” The task of the triumvirate was to form the composition of the conclave: appointed a fourth elector in addition to themselves, the four assembled knights appointed a fifth, and again the resulting five chose a sixth, and so on until the number of sixteen electors (two per language) was reached. Each of the sixteen electors expressed a preference, and the name of the knight who had obtained a majority was submitted to the assembly of knights to ask for ratification of the appointment: if the knights agreed, the new Grand Master was proclaimed. Each Langue was composed of a number of priories: Wignacourt, for many years, had run the Priory of France (one of the four that made up the Langue of France: the others were the Priory of Aquitaine, the Priory of Champagne and the Priory of Corbeil), and a few months before his election as Grand Master he had become Grand Hospitaller, the highest office in the French Langue. The Veronese knight Bartolomeo dal Pozzo (Verona, 1637 - 1722) recounts in his Historia della Sacra Religione militare di S. John Gerosolimitan known as Malta, that orchestrating the election of Wignacourt as Grand Master was above all Friar Ippolito Malaspina (Fosdinovo, 1540 - Malta, 1625), Grand Admiral of the Tongue of Italy, who “having discovered in Wignacourt most noble qualities with loyalty of spirit, and upright intention, began to place him in predicament of Grand Master and to bring him with his Friends.” In that conclave, Malaspina was given the role of “cavalier dell’elettione,” and Bartolomeo dal Pozzo states that the Apuan knight succeeded in bringing his French confrere to obtain the highest office in the Order.

Alof de Wignacourt’s magisterium, which lasted for more than two decades, began at a time of great transformation, which the Order’s power was experiencing at least since the victory over the Ottomans in the Great Siege of 1565. Wignacourt’s magisterium itself had elements of novelty compared to that of the masters who had preceded him, and a clear indication of this is the fact that no other Grand Master had previously had the same, high number of portraits taken by Wignacourt: the aim was to make the Grand Master a figure who could be treated as an equal by other European sovereigns and, at the same time, to limit the interference of ecclesiastical authorities (above all the Inquisition) in Maltese affairs. The Grand Master of the Knights of Malta was, in essence, becoming increasingly important in international relations: an importance definitively sanctioned by the conferral, in 1607, of the title of prince of the Holy Roman Empire that Emperor Rudolph II granted to Wignacourt, who was thus entitled to receive the appellation of “highness” (he was the first Grand Master to be able to boast of this honor). Politically, Wignacourt was not only distinguished by the image he managed to communicate to the other powers: the new Grand Master became an important standard bearer of Christianity, since he organized several campaigns against the Turks and succeeded in reconquering some islands that had fallen under the Ottoman Empire (and his portrait standing in armor has been read by several scholars as his willingness to present himself in the guise of a proud miles Christi). Frequent and victorious raids against the Turks (on the African coast, and in Greece: chronicles mention the knights’ sacking of cities such as Lepanto, Patras and Corinth) enabled Wignacourt to accumulate considerable resources, which were reinvested to improve Malta’s finances and infrastructure: particularly famous is the construction in 1610 of the aqueduct (some fifteen kilometers long) to supply water to Valletta, at a time when the supply of potable water resources was a major problem for the island. Other appropriations were used to build new fortifications to defend the island in order to ward off possible new Turkish attacks (the most obvious symbol of the Grand Master’s action in this regard is probably the Wignacourt Tower that still stands today on the waterfront of the town of St. Paul’s Bay). Still, a further curious aspect of Alof de Wignacourt’s magisterium was his insight into the potential of what we would today call “religious tourism.” In fact, there is a cavern in Malta, known as St. Paul’s Grotto, which is believed to have been the saint’s refuge during his time on the island.Wignacourt arranged for the Order to become the managing body of the grotto with the aim of making it a major international pilgrimage destination, although the project was not successful since there was never the movement of the faithful that the Grand Master hoped to bring to Malta.

|

| Caravaggio, Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt (1607-1608; oil on canvas, 195 x 134 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

|

| Alof de Wignacourt’s aqueduct at Birkirkara (Malta). Ph. Credit |

|

| Wignacourt tower in St. Paul’s Bay. Ph. Credit |

We then know the role Wignacourt played in promoting the arts. We know that as early as 1606, the Grand Master was making efforts to try to bring a painter from Florence to the island (at this time, however, the name of the artist could not be traced). We derive the information from the letters that Wignacourt was exchanging at the time with one of his correspondents in Naples, Friar Giovanni Andrea Capeci, who was serving as the Order’s treasurer in Naples: from the missives we learn that initially the negotiations seemed to be going well, so much so that Wignacourt had already even arranged for the painter to travel to Malta, but for reasons of which we are unaware, the unknown painter would never reach the island. It was at this juncture that the groundwork was laid for Caravaggio’s arrival in Malta: it is likely that it was the marquise Costanza Colonna, who was in correspondence with Wignacourt and whose family had previously given hospitality to the painter, who directed the Grand Master to Caravaggio. However, it is also possible to emphasize the importance of the kinship between the aforementioned Friar Ippolito Malaspina, who, as we have seen, had been very active in Wignacourt’s election as Grand Master, and the banker Ottavio Costa, one of Caravaggio’s first patrons in Rome. In any case, the fact remains that as early as the summer of 1607 Caravaggio, having left Naples where he was at the time, had landed in Malta, despite having been guilty of the crime of murder, which would have prevented him from joining the Order: scholar Rossella Vodret, also resorting to the studies of Keith Sciberras (one of the foremost experts on Maltese artistic affairs), points out that “the fact that the painter probably reached Malta on board a galley of the Order indicates that he must have already enjoyed powerful protection at the time of his departure from Naples. Among the commanders of the Maltese galleys was Costanza Colonna’s son, Fabrizio Sforza-Colonna, who surely knew Caravaggio well: coming from the north, his ships had to stop in Naples only for a short supply of provisions and therefore, Sciberras observes, Caravaggio’s voyage could not have been improvident, but everything must have been ready for days.” Even Wignacourt, Vodret again points out, had difficulties in getting Caravaggio into the Order, since, in December 1607, there are two requests from the Grand Master sent to the pope: “one to obtain the investiture of a man who had committed murder, the other to invest him as a knight.” In the end, however, the pontiff, Paul V, granted his authorization, and Caravaggio, on July 14, 1608, a year after his arrival in Malta, became a “knight of the Magistral Obedience” (the lowest rank: higher ones were reserved for nobles, and the painter was not from an aristocratic family).

In addition to executing the portrait of Wignacourt (whose features, by the way, according to art historian Maurizio Calvesi are to be traced, although this is not a unanimously shared idea, also in the face of the Saint Jerome scribe that the Lombard painter executed, during his stay, for Ippolito Malaspina: it is the painting that Malaspina destined upon his death to the Chapel of the Langue of Italy where it was kept until its daring theft in 1984 and subsequent recovery also thanks to the Carabinieri of the Nucleo Tutela in Rome; following the restoration of the Chapel of Italy it is now replaced with a copy above the tomb of a personage who, though little studied, played a fundamental role in Merisi’s events in Malta), Caravaggio, as is well known, painted his only signed work, the Beheading of St. John the Baptist, in Malta, and as anyone who has read his biography will recall, his experience on the island ended unhappily, since the Lombard artist was arrested for his involvement in a brawl in which a knight, the Asti nobleman Giovanni Rodomonte Roero, was injured. It was August 18, 1608: imprisoned in Fort Sant’Angelo, Caravaggio managed to escape (no doubt aided by some knight) on October 6, never to return to the island. However, as mentioned, the painter, in the short period of time that coincided with his stay in Valletta, managed to execute the Beheading of the Baptist at the express request of Alof de Wignacourt, who was the painting’s direct patron (the Grand Master’s coat of arms is, moreover, on the original frame: this detail has led many leading scholars to consider it an important element in assigning him as Michelangelo Merisi’s patron). The painting was intended to decorate theOratory of St. John Decollate, which remains the most significant artistic and religious undertaking built under Wignacourt’s magisterium.

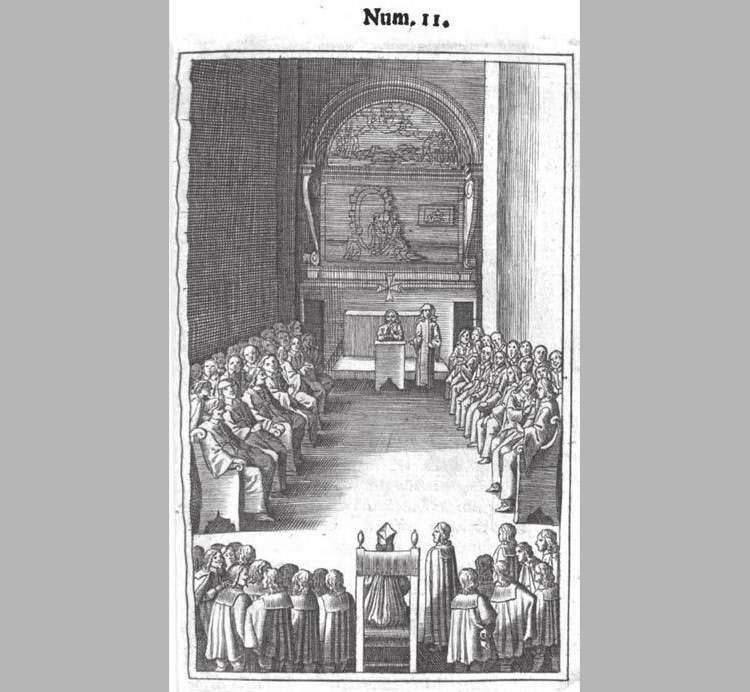

The events of the Oratory were reconstructed in detail in a recent study by Sante Guido and Giuseppe Mantella at a conference held in Valletta in 2013. The foundation of the small church built next to the Maltese capital’s Co-Cathedral dates back to 1602: the project was submitted to Wignacourt by a number of knights who, Guido and Mantella write, “requested that an oratory be erected at the lower end of the church, towards the cemetery, so that in this and all assembled they might better fulfill all their pious and spiritual duties required by the statutes and regulations of their religious profession.” The event is also recalled in Bartolomeo Dal Pozzo’s Historia (“hadva il Gran Maestro nell’anno decorso a supplicatione dalcuni divoti Cavalieri concesso licenza di fabbricarvi un Oratorio a canto alla Chiesa e di riscontro alla Sagrestia di San Giovanni per commodità di frequenatarvi i Sacramenti, instruire i novitii e far altre opere religiore e pi pi pi pi pique, giusta la forma degli Statuti a regolar professione dellOrdine”). The building of the oratory, a small rectangular-bodied room leaning against the right aisle of the Co-cathedral, took barely a year (and in the meantime Wignacourt had granted its titularity to the Confraternity of Mercy, or of the Rosary, which had had to abandon its seat in the convent of Porto Salvo: the assignment, however, did not prevent the knights from attending it): the consecration took place on the day of December 21, 1603, on the feast of St. Thomas the Apostle, during which, Bartolomeo dal Pozzo recalls, “the devout image of the Most Holy Crucifix was raised and, by the confreres of the said Company dressed in their sacks, was transferred to the new Oratory entitled to St. John the Beheaded; to whom and to their rector Friar Girolamo Agliata Ammiraglio, was of the same Oratory given possession and thereupon the Prior of the Church sang the solemn Mass, which was the first that was celebrated there.” The Oratory of St. John Decollate was not only a significant center of the religious life of the knights, but also held very important civic functions: public assemblies were held there in which statutes were read or legal issues were discussed, and it was the place where the trials of the Tribunal of the Look, the body to which the internal justice of the Order was entrusted (the tribunal judged knights who were guilty of some fault), composed of representatives of the Order’s eight languages, were held. In the only seventeenth-century engraving, by the German Wolfgang Kilian (Augsburg, 1581 - 1662), which shows us Caravaggio’s work in the oratory before the alterations that, as will be seen a little later, the room underwent in the late seventeenth century, the oratory appears as a bare enclosed by the altar on which Caravaggio’s Beheading is installed (it should be noted, however, that to the best of our knowledge Kilian was never in Malta and probably based his engraving on a sketch he received from someone residing on the island, as well as on descriptions of the locale). Above the Caravaggesque canvas, however, there is a lunette with a painting now no longer in the oratory, but kept at the Franciscan convent of Rabat in Malta: it is theIntercession of the Baptist to the Virgin for the knights who fell in the Great Siege, a work by the Greek painter Bartholomew Garagona (Senglea, 1584 - 1641) that cloaks the historic episode of the siege of 1565 with deep religiosity. The work dates from around 1625 and, Guido and Mantella point out, is the result of a precise iconographic choice “that had characterized theOratory since the first years of its establishment, with the clear intention of accompanying, with the suggestion of images, the path of formation of the novices and the daily renewal of the promise by the professed brethren.” In the engraving, moreover, we see the Tribunal of the Sguardio assembled: it is likely that in a similar assembly Caravaggio was judged after the brawl in August 1608, when he was sentenced to privatio habitus, expulsion from the Order.

|

| Oratory of San Giovanni Decollato. Ph. Credit Michael Jones |

|

| Oratory of Saint John Decollate |

|

| Caravaggio, Beheading of the Baptist (1608; oil on canvas, 361 x 520 cm; Valletta, St. John Decollate) |

|

| Caravaggio, St. Jerome Writing (1608; oil on canvas, 117 x 157 cm; Valletta, Co-Cathedral of St. John) |

|

| Wolfgang Kilian, Oratorio di San Giovanni Decollato (C. von Osterhausen, Eigentlicher vnd gruendlicher Bericht dessen..., Augsburg 1650) |

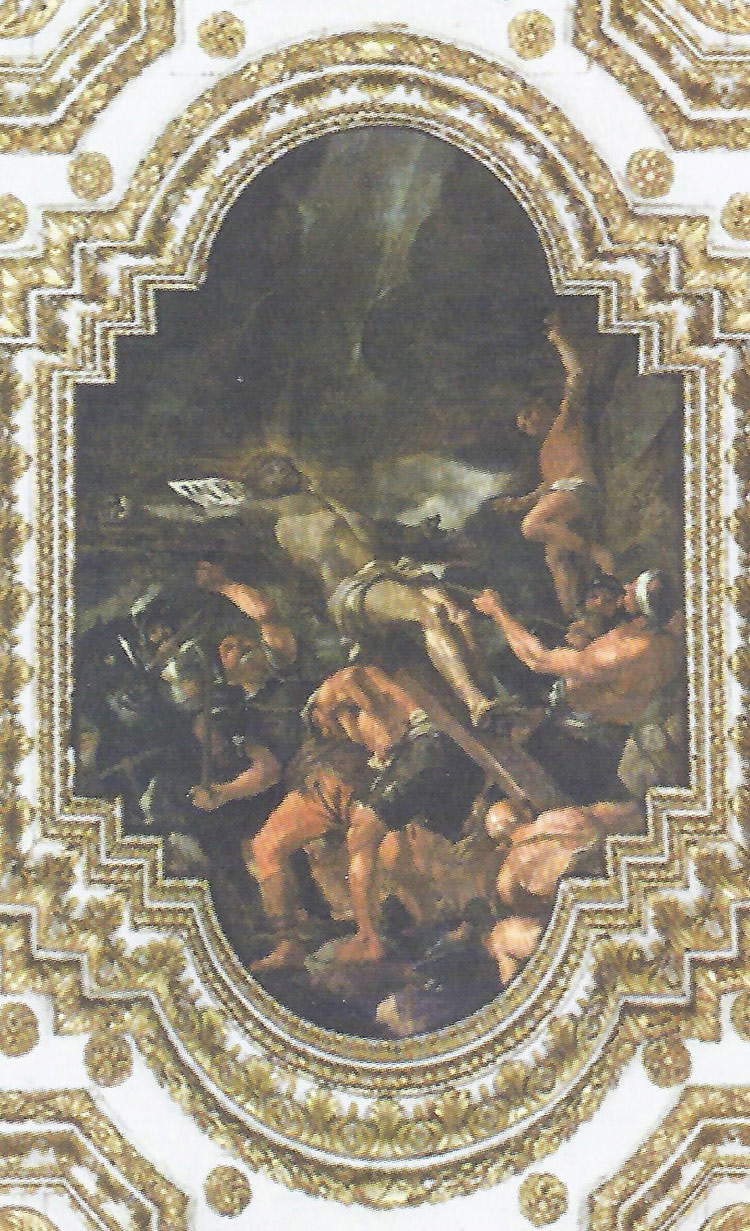

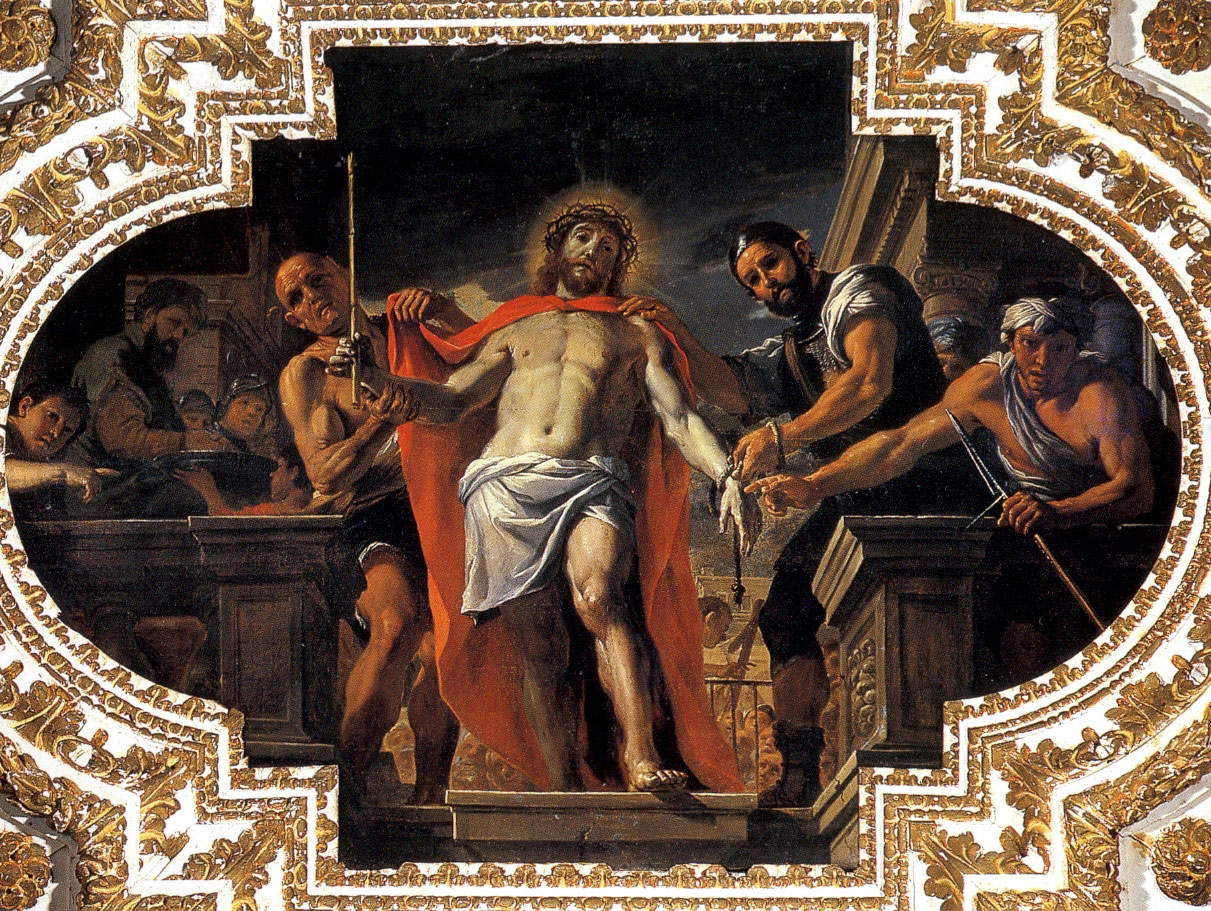

The concluding chapter in the artistic events of the oratory would be written seventy years after Wignacourt and Caravaggio, by another Italian genius, namely the Calabrian Mattia Preti (Taverna, 1613 - Valletta, 1699), who arrived in Malta in 1661. Beginning in 1678 (and continuing until 1695), the Genoese knight Stefano Maria Lomellini, who was prior of England at the time (and would later become prior of Venice), had secured substantial donations to the Oratory of San Giovanni Decollato: it was Lomellini himself who was the great patron of the renovation of the oratory, an operation totally entrusted to Preti at the conclusion of the total makeover of the church-convent tentatively begun in the late 1640s, but which received an enormous boost with the arrival of the painter, a knight of obedience since 1641 by appointment of Pope Urban VIII Barberini, on his first trip to the island and especially with his final move to Malta in the summer of 1661. In the short span of a decade Preti’s design all the chapels of the eight Langues and the great nave were totally transformed in the Baroque style by Preti with painted and gilded carved walls, large sumptuous altarpieces terragne tombstones in Sicilian marble commesso and over all 400 square meters of oil painting you wall with the stories of St. John the Baptist. It was therefore natural to entrust Preti with the “restoration” of the oratory, which appeared bare and antiquated some 70 years after its construction. . The idea of the Calabrian painter was to enlarge the oratory, giving it a new ceiling and a new decorative apparatus updated on the late Baroque taste: the project was approved in July 1679, a few months before the election as Grand Master of a knight of the artist’s country, Gregorio Carafa (Casteltevere, 1615 - La Valletta, 1690), who held the office from 1680 until his death. Mattia Preti first made ten paintings depicting as many of the order’s founding saints and blessed heroes, arranging five on each side on the walls of the oratory (on the right side wall: saint Ubaldesca, blessed Adrian Fortescue, saint Ugo da Genova, blessed Gerardo Sasso; on the left side wall: Saint Tuscany of Verona, Blessed Giorlando of Alemagna, Saint Nicasius, the miracle of Blessed Gerard Sasso; on the apse, on either side of Caravaggio’s Beheading, on the right Blessed Gerard and Raymond du Puy before Saint John the Baptist, and on the left Agnes with the nuns of the order before the Virgin). The ceiling of the oratory was decorated with gilded wooden elements inspired by the ceiling of the Neapolitan church of San Pietro a Maiella with ten canvases by the painter known as “il Cavalier Calabrese,” his last effort in the Neapolitan city; the same solution was devised for the lunette above Caravaggio’s Beheading: Garagona’s painting was removed and an image of the Mater dolorosa was inserted in its place, essentially for two reasons. The first was practical: the Greek artist’s work was in a poor state of preservation and a solution had to be found. The second, on the other hand, was of an ideal nature: in fact, Preti reconfigured the iconographic program of the oratory to introduce the theme of the Passion of Christ, to which the three paintings that Cavalier Calabrese created for the ceiling were connected, allocating them to the mixtilinear spaces that were to house them. These wereEcce homo, Christ Crowned with Thorns and Descent from the Cross. To ensure further majesty to the oratory, Preti thought of lengthening the space of the chancel, with the result that the Decollation was placed to close a space preceded by a large, richly decorated arch, to create “the effect of a chapel within a chapel” (so scholar David M. Stone). And to top it all off, a sculptural group depicting the Crucifixion was placed in front of the Caravaggio painting, which partially obscured the view of the Lombard master’s masterpiece and was only removed in 1958.

Guido and Mantella have published documents from which it can be seen that the change of worship had been deliberated by the Grand Master and his Venerable Council on February 7, 1679: it is worth asking, however, why a new devotional theme had been considered for introduction into the oratory. Stone speaks of reasons of expediency: the Co-cathedral was already devoted to the worship of the Baptist, Preti had previously painted scenes from the saint’s life there, and to repeat the experience would have been redundant. However, there were no works recounting the Passion of Christ in the two houses of worship, and perhaps this could be one of the reasons behind the changes. Stone also puts forward an ideological hypothesis, since the theme of the martyrdom of St. John the Baptist was closely related to the martyrdom of the knights who had given their lives during the Great Siege: many of them were still alive when the oratory was built (so much so that Garagona’s painting was expressly dedicated to the fighters who had lost their lives in the struggles against the Ottomans). Since more than seventy years had passed, since the Turks were no longer a threat and since, in the late seventeenth century, the knights, rather than by the spirit of sacrifice, were motivated by ideals of “nobility, welfare and charity” (so Stone), the oratory as it had been up to that time (a bare and austere room, decorated only with Caravaggio’s painting and Garagona’s) was no longer considered current.

At the conclusion of the work and still under the magisterium of Gregory Carafa, it was decided to exhibit in the oratory, almost a Sancta Sanctorum, the most important and precious relic of the Knights Johnites, the arm of St. John the Baptist, in their possession since 1484, when it was given to Grand Master Pierre d’Aubusson in Rhodes by the Ottoman Sultan Bajazet II, and arrived in Malta in 1530 along with the very few precious things they saved when they lost the island in the Aegean, which had fallen to the Ottomans, and moved to their new seat a few miles of sea from Charles V’s Sicily. Grand Master Carafa, of Calabrian nobility, wanted to have a precious shrine made for the relic (toward which the entire Order had a deep devotion) so that it could be displayed in the oratory of San Giovanni Decollato: thus, in 1686, Carafa commissioned the work from Ciro Ferri (Rome, 1634 - 1689), as can be seen from recently found payment records. The work, the material execution of which was entrusted to the Ticino bronzesmith Francesco Nuvolone, was made in Rome (recalling in part the tabernacle of the New Church of the Oratorian fathers made by the same craftsmen a few years earlier) and finished in 1689, the year in which the reliquary was first displayed in the capital of the Papal State, then sent to Malta and then installed on the altar. It is a work of imposing dimensions, since it measures more than two meters in height: made of silver and gilded bronze, it consists of the theca in the form of a lantern intended to hold the relic, which rests on a step decorated with phytomorphic motifs and the Carafa family coat of arms and is supported on either side by two putti. The shrine itself is richly ornamented with heads of cherubs and additional plant motifs (palms and lilies), and surmounted by a crown holding a cross, flanked by four shells. On either side of the long plinth are two large scrolls, above which two large angels kneel devoutly. The reliquary has not been on display in the oratory since 1977, when it was moved to the Co-cathedral Museum, where it can still be admired today. Moreover, in 2003 it underwent restoration (the work was in fact in a severe state of deterioration, due to wear and tear and centuries of exposure in a very humid place and a short distance from the sea), which made it possible to conduct a thorough cleaning operation and to carry out a conservative treatment.

|

| The ceiling of the oratory of San Giovanni Decollato with canvases by Mattia Preti |

|

| Mattia Preti, Christ Crowned with Thorns (1679-1689; oil on canvas, 227 x 350 cm; Valletta, Oratory of San Giovanni Decollato) |

|

| Mattia Preti, Descent from the Cross (1679-1689; oil on canvas, 306 x 443 cm; Valletta, Oratory of San Giovanni Decollato) |

|

| Mattia Preti, Ecce Homo (1679-1689; oil on canvas, 227 x 350 cm; Valletta, Oratory of San Giovanni Decollato) |

|

| Ciro Ferri (drawing) and Francesco Nuvolone (execution), Reliquary of the Arm of the Baptist (1686-1689; Valletta, Oratory of San Giovanni Decollato). Ph. Credit Hamelin de Guettelet |

The Oratory of St. John Decollate is still today an important center of religious life in Malta and the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and Malta (whose government, however, is no longer based on the island today: in fact, the Grand Master and the Order’s government have resided, since 1834, in the Magistral Palace in Via dei Condotti in Rome): the Maltese Association of the Order, i.e., today’s territorial emanation of the knights in Malta, celebrates the feast of the Order’s patron saint each year on June 24 with a mass and procession involving the Valletta Co-Cathedral and Oratory. Today, however, the two houses of worship are also one of the must-see destinations for those visiting Malta, given their fascination because of their unique blend of history, tradition, spirituality and art. The care and management of Co-Cathedral and Oratory are entrusted to a Foundation that administers the entire religious complex together with the museum in order to protect them (there are frequent restoration works that the Foundation approves), enhance them and manage them as places of faith and culture.

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.