Among the most interesting novelties presented by the recent exhibition Le Signore dell’Arte (in Milan, Palazzo Reale, from March 2 to August 22, 2021) it is possible to include the pioneering though incomplete survey of Claudia del Bufalo (active in Rome between the late 16th and early 17th centuries), a painter of noble birth from the Roman Del Bufalo family, which precisely between the 16th and 17th centuries had reached the heights of its prestige. Originally from Pistoia and settled in Rome at the end of the fifteenth century, they knew how to carve out an important role for themselves in papal Rome to the point that one of their members, Innocent (Rome, 1565/1566 - 1610), obtained the appointment of cardinal (it took place in 1604 under the papacy of Clement VIII: before that, in 1601, Innocent had become bishop of Camerino, and in the same year he had been appointed apostolic nuncio to France).

Claudia del Bufalo’s name is not new to art history: as early as 2008, art historian Patrizia Cavazzini mentioned her among a host of women who tried their hand at painting, and like other noblewomen, such as Sofonisba Anguissola, Lucrezia Quistelli, and Caterina Cantoni, Claudia del Bufalo was also part of that host of women of illustrious birth who devoted themselves to painting for pleasure (a host that may perhaps be even more numerous than we imagine). However, of Claudia del Bufalo we know only one painting: it is the Portrait of Faustina del Bufalo, her sister. It is a work from 1604 and is now owned by Dario del Bufalo (in the recent history of the painting there is a record of it passing at auction at Finarte on October 5, 1999 for just over $21,000). It is curious to note that in the past this canvas was attributed to a man, due to an error in reading the signature at the base of the column, later reported in the 1650 inventory of the Villa Borghese, where the work was once located: in the register, compiled by Giacomo Manilli, Claudia’s name is in fact turned to the masculine (“That of Faustina del Bufalo,” the inventory reads, “is made by Claudio del Bufalo”). An error that has conditioned scholars: in an article published in the Bollettino d’Arte in 1964, even scholar Paola Della Pergola was misled, speaking of “Claudio del Bufalo.”

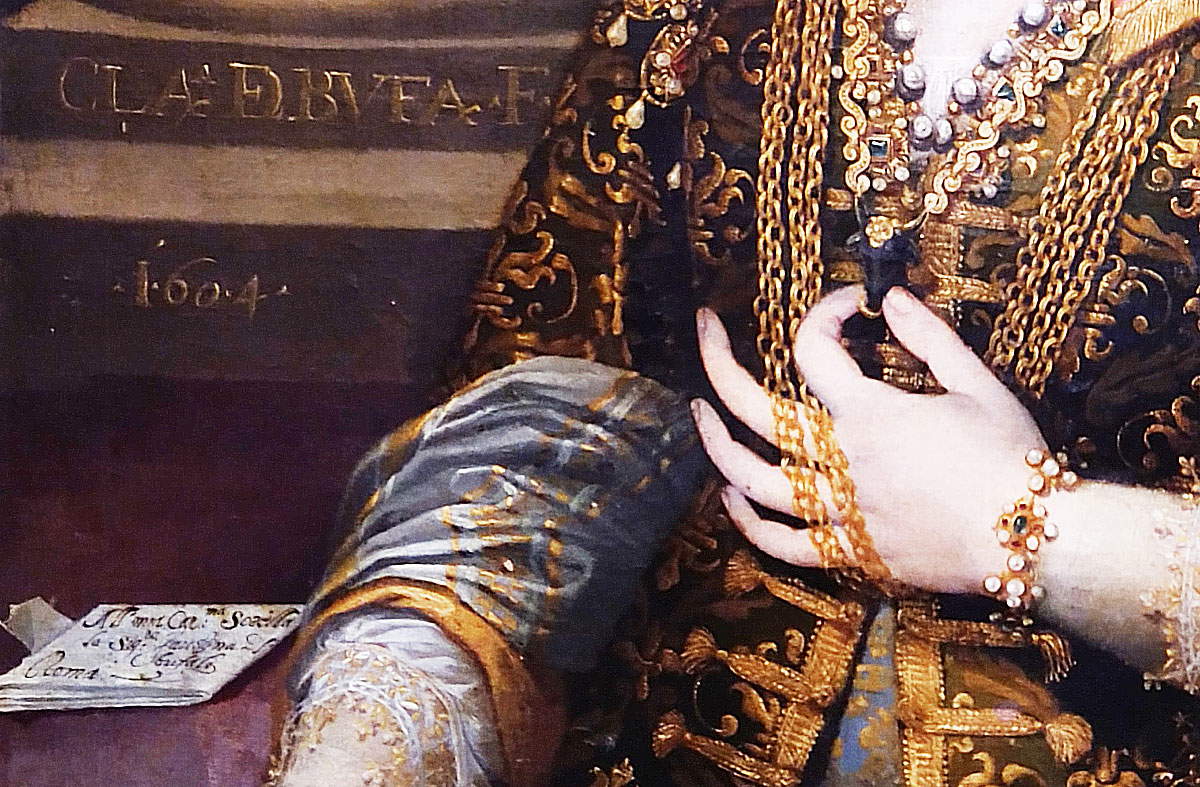

Faustina del Bufalo, in the portrait, is depicted standing in front of a column on the base of which we discern the author’s signature and the date of its making. Dressed in a sumptuous brocade robe that is thickly and richly decorated, Faustina sports many accessories that at the time were accessible only to women from wealthier families: the diadem with the gem set in the lunula (the half-moon-shaped amulet that in ancient Rome was worn for apotropaic purposes by girls and young women until they were married), placed on the top of the head, and then again the double-round pearl necklace and gold chain, the bracelet also with gold, pearls and gems (rubies and emeralds), worn on both the right and left hand. With her left hand, the young woman holds tightly between forefinger and thumb a curious pendant in the shape of a buffalo head, a heraldic reminder of her family. Faustina is portrayed realistically by her sister, who does not give back to the viewer an idealized portrait, but a naturalistic one, showing herself to be an up-to-date and modern painter. That, moreover, Claudia was Faustina’s sister we know for certain from the dedication on the letter we glimpse near her right sleeve: “Allmia Car:ma Sorella / La Sig:ra Faustina Dl / bufalo / Roma.”

Looking at the jewelry we can be certain that Faustina was about to be married. The most revealing detail is precisely the lunula-shaped pendant that decorates the tiara and which, placed thus on the head (instead of around the neck as the ancient Roman women wore it), is an expedient to evoke the image of the goddess Diana, a chaste divinity: a further reference, therefore, to the purity of the girl represented. A well-known symbol of chastity is also the pearl: In Camillo Leonardi’s Speculum lapidum, the treatise on gemmology published in Latin in Venice in 1502, the pearl is called “prima inter gemma candidas” (the first of the candid gems) and was believed to be “ex coelesti rore genita in quibusdam conchis marinis ut ab auctoribus habetur,” or “generated in the shells by the celestial dew, as we learn from the authors” ( Pliny is the author Leonardi had in mind: the birth of the pearl by celestial fertilization was thus why it was associated with chastity). Rubies, because of their red color, are a symbol of love and charity, while emerald, in addition to being a stone dear to the goddess Venus, was thought to further symbolize chastity. Then it will be noticed how the left hand does not have the wedding ring, but is nevertheless wrapped with a few turns of the gold chain, a sign that Faustina had sentimental ties or at least was betrothed. Finally, the right hand rests on a white handkerchief, an object that could have constituted an engagement gift and thus a further allusion to the woman’s status (white is then, again, a symbol of her purity). “In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, chastity, fertility and generosity, as fundamental virtues for a young patrician woman,” scholar Silvia Malaguzzi has written, “are frequently reiterated by accessories and jewelry, especially in portraits intended to document the features of the maiden at the betrothed. The painter’s dedication to her sister seems to indicate the latter and not others as the recipient of the portrait, and yet the pearl necklace and chain, probably added later, would seem to suggest a hypothetical matrimonial destination of the work at least at a later stage.”

Having clarified the iconography and function of the portrait, what is it possible to know about its creator? Again Silvia Malaguzzi, on the occasion of the exhibition Le Signore dell’Arte, has gathered the information we have so far, while hoping that more light will be shed on Claudia del Bufalo in the coming times. According to family memoirs, Claudia may have been the daughter of Quinzio del Bufalo, younger brother of the Innocent mentioned in the opening, and husband of Cassandra di Lorenzo Strozzi: after the latter’s death, Quinzio followed his older brother into an ecclesiastical career, but failed to follow in his footsteps. Five children are documented from the marriage between Quinzio and Cassandra, namely Innocenzo, Silvia, Virginia, Dianora, and Ottavio Giacinto, but no Claudia or any Faustina appear from the records. The hypotheses, Malaguzzi explains, “may be various: either the two sisters, as was in use among the literati of the time, had adopted pseudonyms carefully chosen from proper names of Roman origin; or, Claudia and Faustina belonged to another branch of the family, yet to be identified.”

What is certain is that Claudia must have been a woman of great culture. Meanwhile, she was aware of the meaning of the gems Faustina is wearing in the portrait, which suggests that Claudia must have been familiar with modern treatises and ancient authors, or at any rate she must have been in contact with some scholar who must have explained to her the meaning of such ornaments. In any case, it is certain that she frequented high-level intellectual circles. Not only that: the way Claudia depicts the preposition “del” in front of “Bufalo” in the signature affixed to the column (an interweaving of Roman numerals) that has a precedent in Sofonisba Anguissola’sSelf-Portrait of 1556 preserved at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Malaguzzi explains, gives us “a clear indication of her antiquarian skills as well as the interests of the environment in which she operated.” The choice of handwriting could in fact imply knowledge of a treatise on calligraphy In which he sinsegna à Scriuer ogni sorte lettera, Antica, & Moderna, di qualunque natione, con le sue regole, & misure, & esempi, a work by Giovan Battista Palatino published in Rome in 1545. Again, it will be worth recalling here how, in a collection of sonnets in death of René de Rieux (a French nobleman who drowned in 1609 in the Tiber in Rome in an attempt to save one of his pages), published to accompany the funeral oration of the theologian Jacques Seguier, two lyrics “by Signora Claudia del Bufalo” also appear, recalling the mournful event and celebrating the virtues of the marquis.

Faustina’s portrait, however, may not be the only existing painting of Claudia del Bufalo. In a November 1610 inventory of the rooms in Palazzo di Monte Savello, the Savelli family’s residence (the inventory was published in 1985 by Luigi Spezzaferro in Ricerche d’arte), a “large painting by Claudia del bufalo, representingagli omini mag.ri di casa Savelli” and “an andromeda tied to the rock by Claudia del bufalo’s hand with a black frame” are mentioned. In short: perhaps more news (and more works!) of this artist about whom very little is known so far will emerge from further research.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.