It is the constant merit of Finestre sull’Arte to awaken attention to many extraordinary works of our figurative civilization that, due to solitude or for various reasons, are not normally brought to their actual value and the high admiration they deserve. We therefore set out along these lines by proposing a curious and interesting examination of the unfinished Allegory of Virtue that Correggio likely began in 1521 for Isabella d’Este Gonzaga, and which remained abandoned. We know that the canvas was in Rome as early as 1603 as recorded in an Aldobrandini inventory. This attestation of excellent appreciation, although the work appears unfinished, is very significant, as is the rapid transfer from Emilia to the papal city. The Aldobrandini collections were none other than those of the reigning pope Clement VIII, and the search for Correggio’s rare and highly prized works came from the Carraccan wave that had illuminated Rome with Hannibal and his. Here then was immediate recognition, which later became distant. This Allegrian proof lacked - in the long history of criticism - the attention it was due. The painting is now in the Doria-Pamphilj Gallery in Rome, whose director, Professor Andrea G. De Marchi, decisively reevaluates it, proclaiming it a “superb autograph.” We are dealing with a kind of very long arch resting on two pylons centuries apart, and the work seems to us worthy of special examination.

We wrote an earlier essay on Allegories for Isabella, recalling its fifth centenary (1522-2022), and we refer to that for many observations: see the January issue of this year in Finestre Sull’Arte. We repeat here that the marquise of Mantua asked Antonio Allegri for the two canvases to complete her new Studiolo in Corte Vecchia and paid for them in 1522. These two paintings were to seal the tenacious pictorial theory that already existed in the earlier paintings, and give its closing demonstrations on the grave effects of Evil (Vice), and the sublime triumph of Good (Virtue). We also recalled that the triumphant and crowned figure must presumptively indicate Isabella herself. The final two canvases shine today in the Louvre Gallery, Paris.

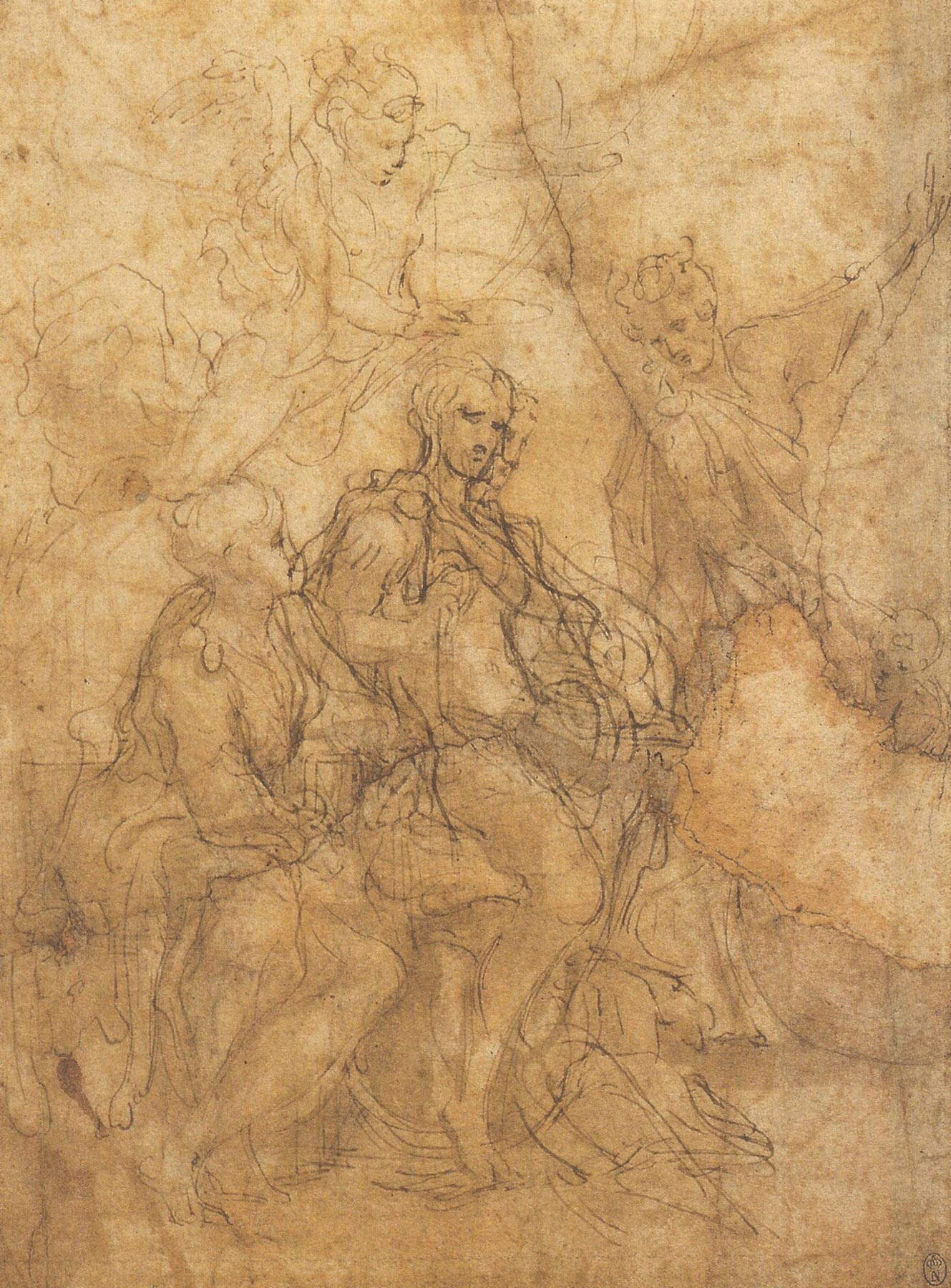

It is very likely that Correggio transited through Mantua in the spring of 1521 and here had the indispensable approaches with the marquise, well known for her punctilious demands on painters and the mythic-symbolic evocations that were to dot every work she wanted. It would be most interesting to have a film on the savory and learned verbal skirmish between the two; if anything, accompanied by the sketches of the 30-year-old master, already glorious of the heavenly fresco of the dome of San Giovanni in Parma, but fate does not grant us such technical recoveries. In order to follow the genesis of the work in question we see an early graphic proof, namely a striking double tracing drawing of the central figures, where in the recto we immediately glimpse the act of the coronation and where we can catch significant details. In this conception, the nudes, so beloved by Correggio, are decidedly leading.

It is not out of place to imagine the marquise’s keen interest in the canvases that were to consecrate her culture and especially her personality at the pinnacle of the Studiolo. Instead, it is difficult to say how Isabella repeatedly put her tongue and finger into the progress of Antonio’s work. She imposed the tempera technique on the intemperate Allegri, who did not refuse and who made a first trial “in corpore vili,” as they used to say: that is, he tried it out on a canvas of precise, applicative dimensions, laying out an essay that was already very convincing.

It remains to be speculated whether this first trial, conducted in lean tempera over a thin layer of sanding of the canvas, was abandoned for technical reasons; in fact, for the two definitive specimens, Correggio treated the polite sanding of the fabric in several layers and switched decisively to fat tempera. But the technical reason does not seem decisive. Out of lively curiosity we might think that “the unfinished” was laid out in Mantua, in the vicinity of the Marchesa, and that Her semantic insights then guided, with great lucidity, the final version of “Virtue.” It is likely that the two Allegories now in the Louvre were later painted in Parma.

We will try to follow an alternation of thoughts between the “superb autograph” of the Doria Pamphilj, which we will call “the unfinished,” and the final version in the Louvre. It will be like discovering the exculpatory conversation between Isabella and Antonio: she all bent on the series of definitions, he extraordinary compositional epitomizer.

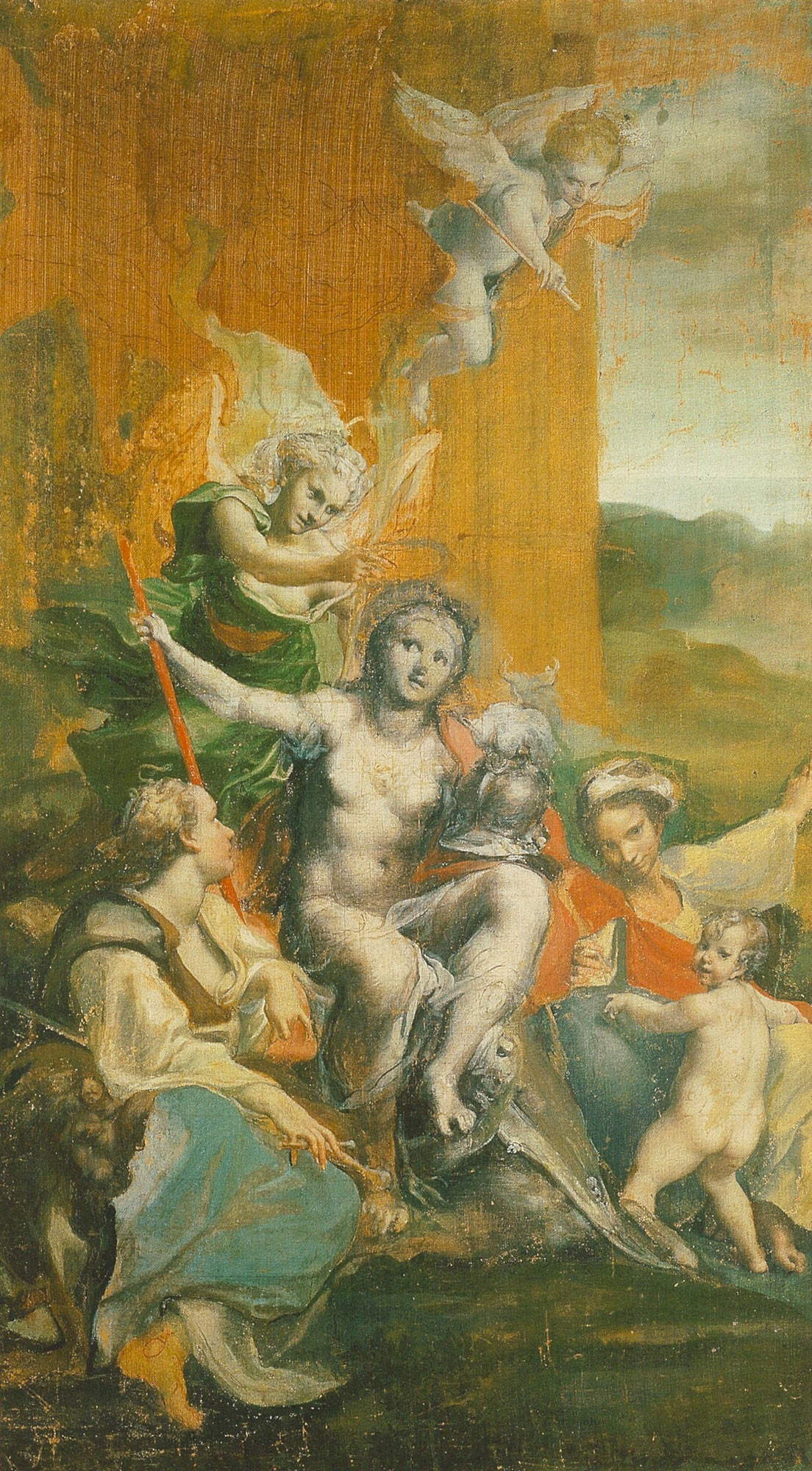

Let us begin with technical observations and immediate figuration in the now Roman proof. Correggio spreads the preparation of plaster and glue, smoothing it out nicely; but the too-white background would have obliged him to excessive chromatic gradations; and here is a second orangey spread, not unmindful of a more neutral Raphaelesque procedure, in the Madonna del Baldacchino. This warm background will greatly help the tones and color fusions; for us-in other cases-it will help in the attributions and dating of certain Allegrian works.

The figures we find in the Unfinished executed in the nude are almost a debt to sculpture; let us not forget the global interest in the arts that Correggio had and his direct love for the human body: here Antony fixes proportions and movements, attentive to planes and depths; Virtue, or Wisdom, is nude, and the modeling carried on with the most refined chiaroscuro suggests that there was an initial search for protagonism entrusted to a symbolic character who is certainly nude: for example, the Truth that discovers everything and overcomes everything. Also contributing to this hypothesis are the very light veils, stretched just along the body, for example on the right arm in similarity to the Minerva of the Chamber of St. Paul, and so the pectoral medusa placed directly on impalpable veils; in addition, the hair is gathered up as in a well radiated capigliara, of distinct Isabellian invention. Not for nothing will this “nuda veritas” inspire Gian Lorenzo Bernini for the Truth in the Borghese Gallery. But the Marquise of Mantua, indefatigable, will choose a different version, far better dressed. Note also the gaze of the protagonist, direct and smug toward the crowning genius, who will then turn to establish a relationship, intentional and desired, with the viewer.

We can then continue our comparative analyses.

The compositional scheme. Comparing the unfinished canvas with the complete one in the Louvre, we notice that the central figure of Wisdom in the first painting holds a more upright, more dominant position; if we recall the graphic diagram we published last January we see that the exact center of the pictorial field is obtained by marking the two large diagonals, which generate the focal point at their intersection but also two sharp equilateral triangles as the lower and upper fields. In the Unfinished, such a center is not emphasized. Instead, in the final Louvre version the central point falls exactly on the mouth of Wisdom thus emanating a series of meanings of thought and heart. The lowering of the figure is justified in comparison with the previous draft by responding to the virtuous need to place Wisdom as the ideal protagonist and more in tune with the semantic grouping of the figures surrounding her. Thus it can turn its eyes outward by connecting to the space of the observer, and overall the scheme allows more breathing room for the three magnificent figures of the Theological Virtues that burst from above in a multidirectional way to complete the Isabellian sylloge. The laurel wreath becomes more ostentatious, whose supporting genius has a gentler face, and the paludamenti of the Great Virtue offer Correggio a chromatic polyphony of a true masterpiece. And we, in this way, realize the very careful processes of refinement between the two versions.

Iconographic echoes. The pictorial modeling of the Unfinished Doria-Pamphilj is strongly monumental in character with resentful overhangs and with spatial eddies around the figures: this is why the Roman canvas is presented with a value that we would call independent. The descriptive conversion that the Louvre canvas achieves transitions to a gentle and, moreover, highly structured symphonic fullness. The iconographic echoes lean almost all on the Camera di San Paolo, that is, on an earlier and grandiose poemical demonstration also registered - as now the Allegories - on the mythic-biblical semiotic admixture. In such admixture Correggio was undoubtedly sublime and extraordinary master. If we look at the peana of praise applied to the figure of Virtue-Wisdom we find first in the Unfinished the attribution to her of the golden “capigliara,” a kind of real crown with rays of light. In the final version, on the other hand, there appears a shell with a pearl in the center placed on the head of the Protagonist: this conferment, a sublime index of a virginal motherhood, we find above the forehead of Diana standing out in the Chamber of St. Paul, and in the same environment in three highly symbolic female figures placed in the lunettes. We invite everyone to these careful observations. Again from the Minerva of the Chamber of St. Paul come the bodice and staff, and that spotted fur of the quiver carried by the putto, which we find in the legging of the Wisdom in the Louvre.

What we shall call the semiotic tumult, gushing from the Isabellian list, deserves our attention. In the Unfinished, the bearer of the Cardinal Virtues, seated to the right of Wisdom (for us on the left) is already provided with almost all attributes and will be faithfully brought back, while between the powerful legs of this first version the head, the dragon’s claws, are confused in energetic execution; then in the accuracy of the finished canvas we see the shield with the Gòrgone, the monster’s canid snout, its abnormal body with the twisted tail and the two different paws: the claw and the goat hoof (τερας). Correggio accurately evokes Athena’s shield with the Gorgon effigy on the outside and the beast on the inside, reminiscent of the serpent Erythonius. It is right to dwell on the latter choices, since for Isabella d’Este evil is indeed multifaceted: the goat in particular has a negative valence among all peoples, and is to be exorcised in any case; here Virtue crushing it with her foot echoes in evidence the role of the Woman of the Apocalypse who conculcates the dragon. In the Roman canvas beautiful is the feminine gesture of taking off the majestic helmet as a sign of victory; again here the symbolic group to the left of the Lady (for us on the right) is sharply defined : the seated woman is already a “cingana” and the very viscous child is dealing with a sphere that is certainly terrestrial since it rests on the ground; he is naked because he is a “newcomer” marking the newly discovered world. In the final version the woman measures with a compass - note - the earthly globe pointing to distant spaces with her other hand.

Still a look at the background of the two paintings is necessary. In the Doria-Pamphilj Gallery canvas, the foreground proda is hurried and dark; behind the figures Correggio has laid out for the most part that second preparation that appears to be waiting for completion, and it is difficult to discern in this wide chromatic backdrop an architectural parastas, as has been written. Above, straggling out of the ochre-orange preparation, stands out almost prodigiously the winged flying figure we shall denote as the Faith; beside it some careful signs are the traces of a continuation already cogitated. The landscape, though of sketchy execution, spreads a river among the mountains with a lyrical landscape effect; the sky is of clear luminous aurora, while the upper part was perhaps already destined for a vegetal reappearance. Here is the great value of the Roman tempera, which - out of curiosity - is called “a concert of women” in ancient inventories.

With this canvas Antonio Allegri departed from Mantua, laden with all the semantic-defining instruction that the Este marquise had given him, and went on to complete one of the most articulate and most reworked works of his career, but happily concluded. In the Allegory of Vice he harmoniously found an exceptionally expansive naturalistic enclosure, but in the Allegory of Virtue he exalted the character of Isabella, superbly set the Solomonic columns of Wisdom (another beautiful connection with the vegetation of St. Paul’s), regimented the waters, but-above all-he gave the Italian Renaissance the sovereign stigma of artistic significance.

Let us close with an invigorating comparison.

The author of this article: Giuseppe Adani

Membro dell’Accademia Clementina, monografista del Correggio.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.