Since my studies have sometimes led me to take an interest in Correggio’s particular subjects and in his relations with the Gonzaga courts, with which he had an evocative continuity of relations, I can now present a result that illuminates a work of his, considered minor but very singular. It is the Ritratto virile preserved in the Museo del Castello Sforzesco in Milan, more correctly referred to as Ritratto d’uomo che legge un libro (Portrait of a Man Reading a Book). As is the case with several of Allegri’s mobile paintings, the dating is intuitive and may fluctuate, but it is sensible judgment to place it in the period immediately following the Camera di San Paolo, that is, strictly close to 1520. The pictorial fullness bears witness to this.

It is important to think intensely about this period of Italian art that had reached what we might call “the fullness of the Renaissance.” This cultural and artistic stage had been prepared by an author of enormous magnitude, Pietro Bembo, to whom a global evidence of linguistic, historical-antic, literary-poetic engagement in full register, and custom, attributed the title of “inventor of the Renaissance.” Without wishing to refer back to an accumulation of studies, publications, and events, we can only remark here how “the Renaissance” was, in the first thirty years of the sixteenth century, a phenomenon inextricably linked with court life. A curious reader may object that Correggio was never a courtier, even as a painter, but we must all allow, like a bird’s-eye view, that the many noble and religious personages whom the young Allegri frequented in the Po Valley area were imbued with the culture and intellectual bearing that Bembo had sprinkled among the Italian courts. In fact, in that period he painted the Camera di San Paolo (an archeological-symbolic poem in a Christian key), the admirable Allegories for the studiolo of Isabella d’Este, and the superb and lovable Ritratto della Contessa Veronica Gàmbara (Portrait of Countess Veronica Gàmbara), replete with elevated inductions of rank and costume.

And it was precisely in the web of travels between Correggio, San Benedetto, Mantua and Parma that Correggio met Gianfrancesco Gonzaga, marquis of Luzzara. The Gonzaga network had acquired power and riches, but its members needed to “pull themselves together,” urged also by Isabella (and also, more distantly, by their countryman Baldassarre Castiglione, a close friend of Raphael); indeed, several of them sought to form and behave, even inwardly, according to the dictates of the true motives of full humanism. “Court” in fact meant courtesy, poetry, love of beauty, culture....

It seems to me that all this, together with the sublimated evocation of the Gonzaga emblem of the Cervetta, is made evident in the embrace that the painter Antonio gives to his friend Gianfrancesco.

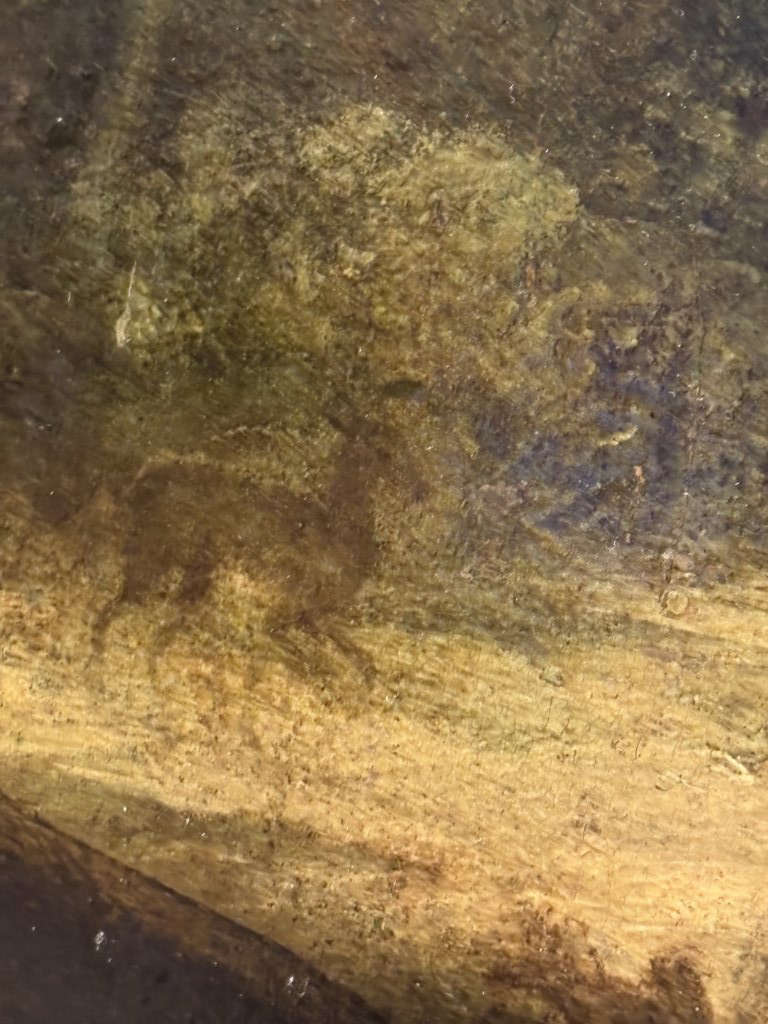

The painting known so far as Portrait of a Man Reading a Book or Portrait of a Gentleman with the "Petrarchino," datable to about 1520, is proposed here as the Portrait of Gianfrancesco Gonzaga Marquis of Luzzara (1488-1525) (Fig. 1). As a preface, we refer to a passage by Giuseppe Adani who believes that the background, like the subject: “is itself enigmatic, with the tangled forest occluding the sky, and with the running of a fugitive deer: obvious allusions to the challenging quests of thought. ”1

The Portrait has been prominently published by David Ekserdjian in his seminal work Correggio,2 and here the celebrated scholar with happy insight points to its noble necessity as a revealing element; in fact, the study that led me to advance the hypothesis on the identity of the subject, started precisely from the detail of the deer present in the landscape that serves as the background of the portrait itself (Fig. 2). In spite of the ravages of time that have made the most minute details less legible, however, it is still clearly evident the presence at the prow of the forest on the right, of an animal that possesses all the morphological characters of a doe, distinguishable from the male specimen by the lack of antlers. This seemingly minor detail about the animal depicted is instead fundamental in linking the character portrayed to the Gonzaga family: the feat of the “Cervetta” is a well-known Gonzaga emblem already adopted by the Duke of Mantua, Francesco II Gonzaga (1466-1519), cousin of the same Gianfrancesco Gonzaga marquis of Luzzara depicted in the Sforza castle portrait.

We still have evidence of Francesco II’s emblem in the mural decoration of the western lunette of the Camera del Sole on the ground floor of the Castle of San Giorgio in Mantua, commissioned by the duke himself and datable between 1484 and 1519; here, a circular heraldic emblem presented within a garland of foliage and fruit, represents the feat of the Cervetta: a white doe with a raised snout stands out within a red field with the motto “Bider craft” (against force) inscribed in a cartouche3 (Fig. 3). The close relationship between the Gonzagas and the symbol of the Cervetta was thus widely known at the time the Correggio portrait was made.

As proof of the link of the Gonzaga symbol with the territories afferent to Gianfrancesco Gonzaga, it should be mentioned that the Cervetta enterprise was later revived, with the addition of a laurel tree and the motto “Nessun mi tocchi” (Fig. 4), by Lucrezia Gonzaga da Gazzuolo (1522-1576), a literary noblewoman sung by Matteo Bandello, who lived at the court of her uncle Aloisio Gonzaga (1494-1549), brother of Gianfrancesco Gonzaga himself, marquis of Luzzara, and was entrusted with the education of Ginevra Rangoni, Aloisio’s wife. A symbol, that of the Cervetta, without a shadow of a doubt recurring in the cultured circles gravitating around the Gonzaga courts, firmly intertwined by both family and cultural ties4.

Having identified the logical connection between the Gonzaga lineage and the subject portrayed by Correggio, it remains to prove his identity with Gianfrancesco Gonzaga, marquis of Luzzara. Coming to the rescue is the rich repertoire of Gonzaga portraits represented by the collection of Ambras Castle in Innsbruck, now preserved at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and clearly documented in the volume I ritratti gonzagheschi della collezione di Ambras by Giuseppe Amadei and Ercolano Marani5. The Gonzaga portrait collection was commissioned by Archduke Ferdinand of Austria, governor of Tyrol (1529-1595), who in 1582 married Anna Caterina Gonzaga (1566-1621), daughter of William I Gonzaga (1538-1587). On that occasion, through the court in Mantua, the archduke requested from the various members of the lineage portraits of those who had exercised dominion over Mantua and in ample addition, images of the Gonzaga princely lineage descended from Gianfrancesco (1395-1444) first marquis of Mantua and first prince of the Holy Roman Empire.

It is important to note that around 1582 the Gonzaga of Luzzara of the first branch of the line of Rudolph6, direct descendants of the Gianfrancesco in the Correggio portrait under consideration, also lived in Mantua in palaces of their own. The archduke therefore should have found no difficulty in requesting their effigies, which were painted from life for the occasion. For the other now deceased members of the family, including Gianfrancesco, Amedei and Marani7 rightly argue that the anonymous painter in charge took as a model other already existing portraits or sculptures that represented them and that were present at the time in the Gonzaga residences in Luzzara. In the archduke’s collection today we find five paintings belonging to the Luzzara branch and fortunately among them Gianfrancesco’s (Fig. 5).

A direct comparison between Correggio’s portrait and the portrait in the collection of Ferdinand of Austria seems to leave no doubt as to the identity of the personage. The coincidences appear surprising to say the least, especially if we dwell on the somatic features (high cheekbones, small mouth and aquiline nose) and the hairstyle of hair, beard and mustache. Also depicted in the two portraits is a black headdress of identical style, which no other Gonzaga depicted in Ambras’s collection wears; this would suggest a distinctive peculiarity of Gianfrancesco’s attire perhaps taken up several times in his portraits.

Essential to the understanding of the painting is an analysis that temporally relates the date of execution of the work to the age of Gianfrancesco as well as of the people who were part of his entourage. Let us first recall that around 1520, when Correggio painted the work, Gianfrancesco was thirty-two years old, an entirely plausible age for the subject depicted. Comparing birth dates we also note that the two were almost the same age, Allegri being only one year younger. Considering the common court acquaintances, we can assume that they knew each other. By the way, it should be noted that also in 1520-21 Correggio executed the Hermitage Portrait of a Gentlewoman, which would certainly depict Veronica Gàmbara (1485-1550) or in the past, for a few others, Ginevra Rangoni (1487 - 1540); in any case, they would be two noblewomen who were also almost the same age as Gianfrancesco (1488-1525) and no doubt in close relationship with each other. Ariosto mentioned them both in the 46th canto of Orlando Furioso where he describes the Correggio court: "...Mamma e Ginevra e l’altre da Correggio veggo del molo in su l’estremo corno: Veronica da Gambara è con loro... ". Ginevra Rangoni, formerly the widow of the Count of Correggio Giangaleazzo, eventually also became Gianfrancesco’s sister-in-law in 1519, when she married his brother Aloisio Gonzaga (1494-1549) and was entrusted with the education of the young Lucrezia Gonzaga da Gazzuolo, already mentioned above in connection with the Cervetta emblem that she too later adopted.

The two portraits by Correggio are thus in very close relation both in terms of the date of execution, which is almost coincidental, and in terms of the possible subjects depicted so far hypothesized and undoubtedly linked by relations of acquaintance, kinship if not friendship, between them and plausibly with the peer Antonio Allegri himself.

As proof that Correggio’s portrait dedications were always motivated by personal motives, mention should also be made of the Portrait of the physician Giovanni Battista Lombardi (c. 1513) (Fig. 6), the third Allegri portrait known to date and already judged with extraordinary admiration by Francesco Scannelli8. The work represents a cherished pictorial celebration that Correggio offered to his teacher9 who reciprocated with the gift of a voluminous treatise on geography10.

TheMan Reading a Book, in particular, makes one think about the relationship between the painter and the subject. It is a quick portrait on a technique singular for Correggio: thick paper, execution in oil, and the shot from the right of an obvious friend (far more than a patron) in full freedom. The depth of the plane behind makes the man appear to be standing, thus standing still for a few moments during a meditative walk, and the painter can pick him up close, with a fairly preemptive perspective brim that makes a rather curious concave elliptical arc, such that we can see from above the headdress and face, and then bring it up to the level of the hand with the book. The degrees of this arch at first glance are hardly perceptible to us observers, but masterfully conducted by the artist.

Correggio calls the figure, which is a bust in its own right, in full proximity to the “visual picture,” so that the living presence of the friend has total figurative ownership of it. He also recasts its face on all sides with obscure spreads (the headdress, the hair and beard, and that broad vestment of the aristocratic scarf jacket) that overshadow on all sides, but do not at all extinguish the full features of the face, on the contrary, they render them with a more penetrating luminosity.

This is evidently an intimate portrait, with which the artist wishes to capture the immediacy of a gesture, a work marked by that perceptible truth of representation proper to a portrait executed from life. Such a peculiarity gives us further assurance that it actually corresponds to the real features of Gianfrancesco, here portrayed without any official or celebratory character, but in a spontaneous pose, absorbed in reading (Fig. 7).

As evidence of a possible longstanding direct relationship between the artist and the marquis, we recall the presence in Luzzara of two works by Allegri at the church of the Augustinian friars, which had already been built less than two decades earlier by Caterina Pico (d. 1501), the marquis’ mother. The existence in Luzzara of two works by Correggio is known through a news item published at the time by Bertolotti11 in his collection of writings and documents on the relations of artists with the Gonzagas, where a letter dated Rome, September 8, 1592, appears, in which the painter and intermediary Pietro Facchetti indicates to Duke Vincenzo I Gonzaga, among other works to be added to his collection, precisely a Christ Carrying the Cross, by the hand of Correggio, and which was then kept in a chapel of the Friars of sant’Agnese in Luzzara along with another painting by the same artist of “a Madonna with S.G.B. with another third figure of a standing saint,” still unidentified today.

The Christ Carrying the Cross, on the other hand, is a known work today, already traced in a private collection by the writer,12 dating to 1513-151413, when Gianfrancesco, already marquis of Luzzara was 25 and Correggio 24. Caterina Pico at those dates was by then deceased and, in Luzzara, the commissioner of the Christ carrying the cross could likely have been the marquis himself, moved by a desire to pay homage to his mother and the church she wanted.

It would therefore be plausible that that between Allegri and Gianfrancesco Gonzaga was a relationship of acquaintance protracted over the years, and the specific “informal” character of the portrait investigated above leads one to think that it was a ’friendship. As Giuseppe Adani has pointed out, a particular closeness between the painter and the subject emerges in this work: “Correggio went beyond the traditional vision offered by a painting, where the viewer stands outside the space offered by the painting itself. Here the artist succeeds in making the viewer have the privilege of participating in the very space of the man portrayed: he stands close to him and breathes with him. ”14

The figure of the noble reader has two striking terms of encounter: one is each one of us, he is the listener, the attentive friend, who could repeat the pronouncement in action of his interlocutor’s lips; and the other is the almost cosmic immersion of this event that takes place in the totally naturalistic embrace of a forest, a place of mysteries and poetic throbs, which gathers the wind and the sun. The farthest thin trunks are bent and their wisps sway; in the middle stretches a light that supports the color scheme of the painting and on which a doe runs; while to the right of the effigy whisper closer the leaves of an ancient tree: a literary statement of remarkable cultural depth.

Certainly the object that we feel is so close and on which we, too, might cast our gaze is the book, the precious little printed artifact that Andrea Muzzi referred to as a “Petrarchino ”15 (Fig. 8), that is, an edition of Petrarch’s rhymes (already circulated before 1520) much sought after by literati, scholars and nobles. Thus flows from the quick portrait, an extraordinary specificity of Correggio, who always painted thoughts! There is no figure of such a painter who does not truthfully express a thought, that is, a surfacing expression, an intimate meditation, or a palpitating dialectic. In this Correggio has achieved that truth of colloquy which the purely high imaginative quality of the early sixteenth century had not touched. Here, too, the nobleman who is effigyed thinks intensely and communicates in the poet’s words “i dì miei più leggier che nessun cervo fuggir come ombra... ”16. So this manly effigy is not simply the “portrait of a gesture” as the authors of the beautiful exhibition Pietro Bembo and the Invention of theRenaissance17 have happily indicated, but the true “portrait of a thought.”

Certainly above a vast proto-sixteenth-century production of portraits by excellent artists including Giorgione (Fig. 9, 10), there was vigor in that vibrant induction, cultural and amorous, proposed by Pietro Bembo’s Asolani, written between 1497 and 1502 and published in 1505 by Aldo Manuzio, almost perfectly coinciding with the first printed realization, in manual format, of Petrarch’s Canzoniere. Thus there was that general phenomenon that involved the Italian courts. It would be worthwhile here to take up Stephen J. Campbell’s fine essay in the catalog of the above-mentioned exhibition, but we limit ourselves to considering how the impact of humanism had found the very attentive Correggio, who, while never allowing himself to be caught up in a lingering atmosphere of a literary character, understood it fully. Hence the portraits of Veronica Gàmbara (Fig. 11) and Gianfrancesco Gonzaga, where in the latter the intensity of communio with the subject may not even necessitate direct vision of the eyes and where the presence of a doe in the background, recalls the words of Psalm 41 (“as a doe yearns for the fountains of waters... ”), so the reader yearns for the joy of the search for wisdom.

Antonino Bertolotti, Artists in relation to the Gonzaga lords of Mantua: research and studies in the Mantuan archives, Modena 1885.

Cecil Gould, The paintings of Correggio, London 1976.

Giuseppe Amadei, Ercolano Marani, I ritratti gonzagheschi della collezione di Ambras, Mantua, Banca Agricola Mantovana, 1978.

Andrea Muzzi, Correggio and the Cassinese congregation, S.P.E.S., Florence, 1982.

David Ekserdjian, Correggio, Italian edition, Cinisello Balsamo, Edizioni Amilcare Pizzi, 1997.

Elio Monducci, Correggio, life and works in documentary sources, Cinisello Balsamo, SilvanaEditoriale, 2004.

Giuseppe Adani, Correggio. Pittore universale, SilvanaEditoriale, Cinisello Balsamo, 2007.

Guido Beltramini, Davide Gasparotto, Adolfo Tura, Pietro Bembo e l’invenzione del Rinascimento, exhibition catalog, Marsilio, Padua, 2013.

Giuseppe Adani, Correggio. The genius and the works, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo, 2020.

1 Giuseppe Adani, Correggio. Pittore universale, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo, 2007, p. 27.

2 David Ekserdjian, Correggio, Italian edition, Edizioni Amilcare Pizzi, Cinisello Balsamo, 1997, p. 166.

3 See the card in General Catalog of Cultural Heritage, nazonal catalog code 0303267445-2.1.

4 We also find the Cervetta emblem in the frieze of the Hall of Myths in Palazzo del Giardino in Sabbioneta where a fresco depicts a small doe with one paw raised, intent on looking at the sun and wrapped in a scroll with the motto “Bider craft,” against force, symbolizing the virtue of meekness.

5 Giuseppe Amadei, Ercolano Marani, I ritratti gonzagheschi della collezione di Ambras, Mantua, Banca Agricola Mantovana, 1978, pp. 163-164, no. 69.

6 Ibid. p. 10.

7 Ibid. p. 11.

8 Francesco Scannelli, Il microcosmo della pittura, Cesena, Neri, 1657.

9 This is Giovanni Battista Lombardi, physician and scientist (1450 c - 1526), a university lecturer in Ferrara and Bologna who gave Allegri a private study cycle probably sponsored by Countess Veronica Gàmbara.

10 Elio Monducci, Il Correggio, la vita e le opere nelle fonti documentarie, Cinisello Balsamo, SilvanaEditoriale, 2004.

11 A. Bertolotti, Artisti in relazione coi Gonzaga signori di Mantova: ricerche e studi negli archivi mantovani, Modena 1885, pp.28-29.

12 The work was later attributed to Correggio by Eugenio Riccomini, who dated it to the early 1510s; it was later published by Giuseppe Adani with a date of 1513-1514.

13 Giuseppe Adani, Correggio. Il genio e le opere, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo, 2020, p. 130, no. 99.

14 Ibid. p. 97, no. 72.

15 A. Muzzi, Il Correggio e la congregazione cassinese, S.P.E.S., Florence, 1982, p. 46.

16 Francesco Petrarch, Canzoniere, critical text and introduction by Gianfranco Contini, annotations by Daniele Ponchiroli, Turin, Giulio Einaudi editore, 1964.

17 G. Beltramini, D. Gasparotto, A. Tura, Pietro Bembo and the Invention of the Renaissance. Exhibition catalog, Marsilio, Padua, 2013.

The author of this article: Marco Cerruti

Marco Cerruti è nato a Milano nel 1977. Laureato in architettura, storico ed estimatore d’arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.