For decades they have been among the most prominent names inglobal contemporary art. Market icons, stars of record auctions, celebrated at museums and biennials, pursued by collectors and curators. Each with a recognizable universe: Jeff Koons and the hyper-lucency of desire, Damien Hirst and death as spectacle, Takashi Murakami and the glittering surface of Japanese pop, KAWS and the toy aesthetic elevated to art, JR and street art with a humanist face. But today, in an age increasingly attentive to complexity,social urgency, and depth of artistic thought, something is cracking. Do these artists still convince? Do they really speak to the present? Or are we faced with an art that has stopped questioning and merely replicates itself? Is it possible that while they remain “relevant” to the market, they have lost the vital drive that makes a work truly necessary?

Jeff Koons is the exemplary case of an artist who has permanently merged art and the market. His works, famous for their mirrored surface, hyper-saturated colors, and toy-like proportions, have invaded museums, foundations, hotels, and airports, becoming status symbols of a postmodern aesthetic founded on excess and spectacle. But today, that same aesthetic is beginning to show its limits. Its balloon dogs, its giant hearts, its Gazing Balls seem closer to the language of decorative design than to a true critical operation. The ostentation of “empty beauty,” which in the 1980s might have sounded like provocation, now appears as a repeated formula. The Paris show in Versailles (2008) caused a stir; the recent exhibition in Doha (2021), on the other hand, went almost unnoticed. Perhaps Koons has met his challenge: he has shown that art can be purely an object of consumption. But for that very reason, today, his work risks being anything but living art.

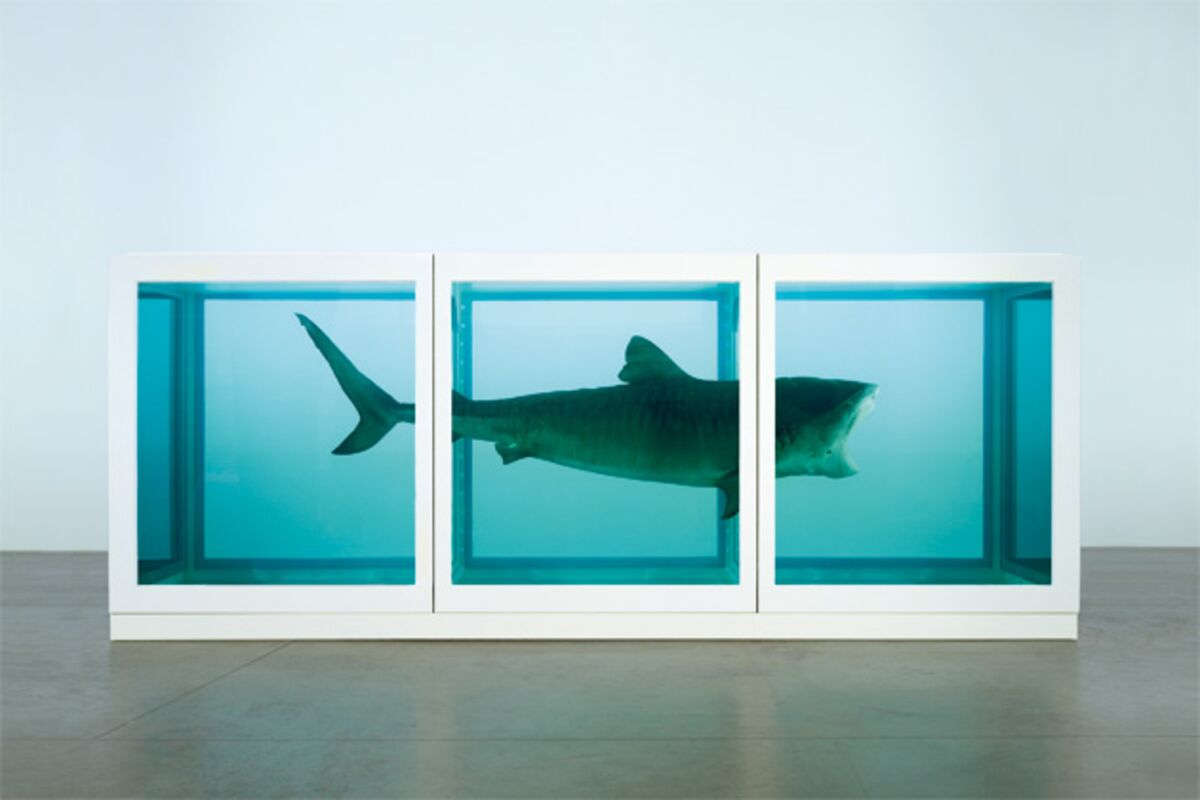

If Koons is the champion of glossy desire, Damien Hirst is the master of memento mori turned spectacle. From the shark in formaldehyde(The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living) to the diamond-studded skull(For the Love of God), his art has always played with obsession with death, decomposition, and value. But how many times can the same concept be repeated? In recent years, Hirst has multiplied his productions: butterflies, cabinets, pointillism a la Spot Paintings, and above all the colossal staging of Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable (2017), a fake archaeological find recreated through Hollywood means, criticized for its self-aggrandizement devoid of real content. Even the NFT project The Currency, by which he burned thousands of drawings to “reflect on value,” seemed more likeamarketing operation than an authentic gesture. What remains of Hirst today is more the signature than thework. The system loves him, but the more observant public is beginning to wonder: is it still art or is it an exercise in power?

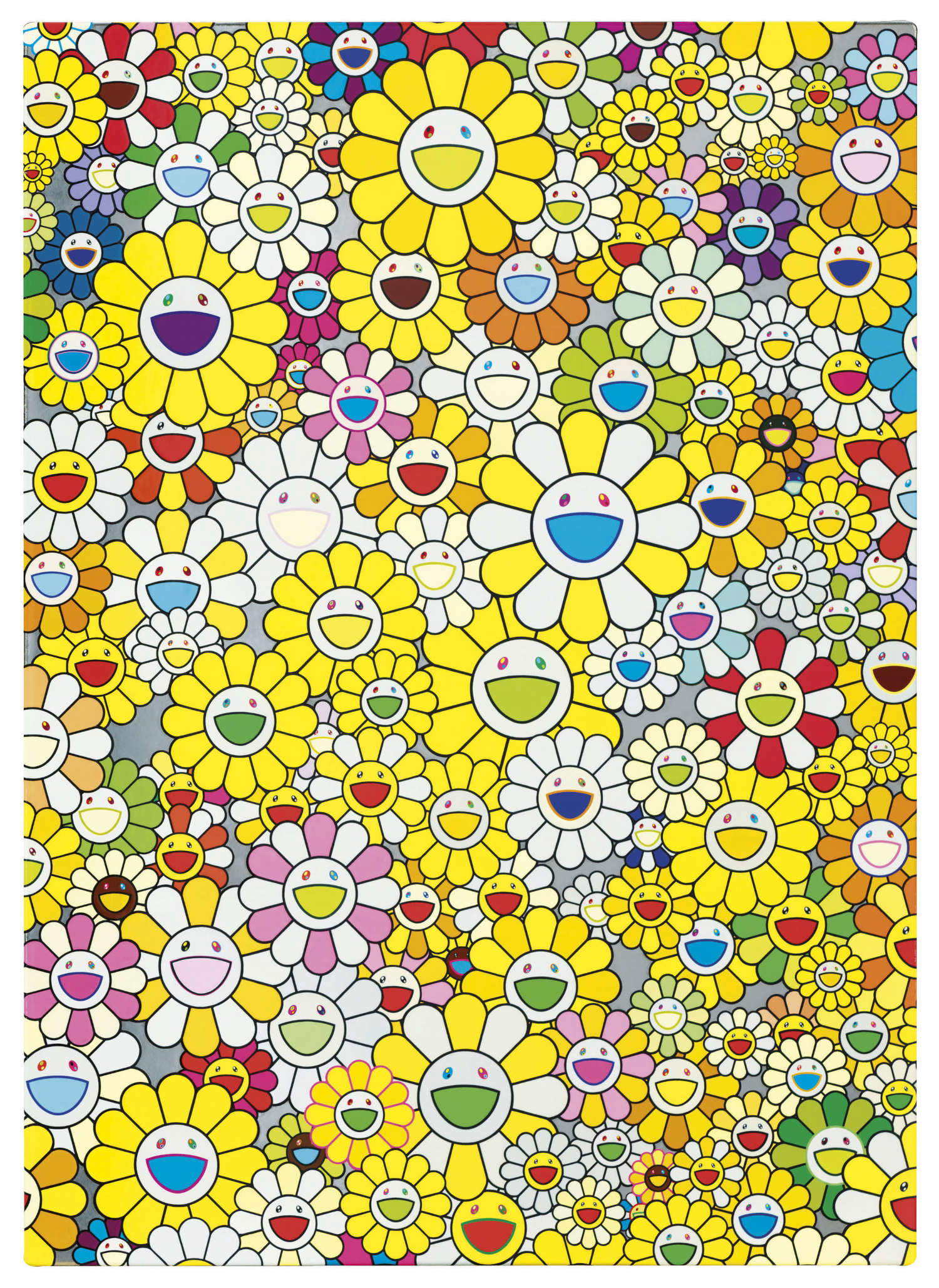

Murakami has been instrumental in bringingJapanese aesthetics to the heart of global art. His Superflat style, with which he fuses manga, Buddhist spirituality, anime, and Japanese tradition, has redefined the boundary between high culture and pop culture. But for how many years have we been seeing the same stylized smiles, the same colorful flowers, the same two-dimensional figures? The impression is that Murakami, from being a radical artist, has become a merchandise producer. From collaborations with Louis Vuitton to collaborations with Billie Eilish, via sneakers and NFTs, his universe has expanded by leaps and bounds. But the proliferation of image has subtracted complexity from content. The message has dissolved into decoration. Sure, the language is recognizable, powerful, commercial. But where has the critical charge gone? The reflection on atomic trauma, on Japanese cultural history, on visual consumption? Today Murakami seems more interested in producing global mascots than works that interrogate reality.

KAWS (Brian Donnelly) is the most emblematic case of the transition fromart to brand. Born as a street artist, he became known for his reinterpretations of pop characters, Mickey Mouse, SpongeBob, The Simpsons, with X-eyes and melancholy postures. From there, an unstoppable rise: museum exhibitions, giant sculptures, collaborations with Dior, Nike, Uniqlo, Samsung. The problem?The work is always the same. The dimensions, materials, colors change, but the figure, the Companion, remains the same, like a logo. There are no developments, transformations, neither conceptual nor formal. Only multiplication. In a world where art should interrogate uniqueness and identity, KAWS produces objects that are replicable, desirable, but totally risk-free. Is he an artist or a luxury designer? His works appeal to collectors because they seem reassuring, familiar, saleable. But it is precisely this predictability that undermines their critical value.

JR is perhaps the most paradoxical case: an artist who presents himself as socially engaged, but who often makes inoffensive projects. His large photographs pasted in working-class neighborhoods, in refugee camps, on city walls have the ambition to “give a voice” to those who do not have one. But the language is always the same: faces in black and white, emotional blow-ups, universal messages. The result? Visually powerful works, but devoid of analysis. There is never real conflict or denunciation. The humanity JR narrates is generic, pacified, “beautiful” in the most rhetorical sense. Even his most ambitious projects, such as Inside Out or the image on the facade of the Louvre, appear as symbolic gestures with no real impact. In an age of structural inequality, geopolitical tensions, and environmental crisis, it is to be expected that art should go beyond easy emotion. And JR, while declaring his intention to make art “for everyone,” seems to construct simplified narratives suitable for Instagram and an audience that seeks confirmation, not questions.

Koons, Hirst, Murakami, KAWS, JR: beloved, celebrated, best-selling artists. But today more than ever they seem to live in the reflection of their icons. They have created a recognizable, effective, but in many cases crystallized aesthetic. Initial strength has turned into routine. Innovation into repetition. Breakage into style.

This is not to deny their historical role, nor to disavow their talent. But it is legitimate to ask: Are they still pushing the boundaries ofart? Or are they just managing their symbolic capital? In a landscape where new generations of artists bring to the forefront practices rooted in territories, conflicts, bodies and personal histories, the model of the global superstar appears increasingly tired. Art needs vitality, not rent. Of risk, not marketing. And perhaps it is time for the system to realize this, too.

The author of this article: Federica Schneck

Federica Schneck, classe 1996, è curatrice indipendente e social media manager. Dopo aver conseguito la laurea magistrale in storia dell’arte contemporanea presso l’Università di Pisa, ha inoltre conseguito numerosi corsi certificati concentrati sul mercato dell’arte, il marketing e le innovazioni digitali in campo culturale ed artistico. Lavora come curatrice, spaziando dalle gallerie e le collezioni private fino ad arrivare alle fiere d’arte, e la sua carriera si concentra sulla scoperta e la promozione di straordinari artisti emergenti e sulla creazione di esperienze artistiche significative per il pubblico, attraverso la narrazione di storie uniche.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.