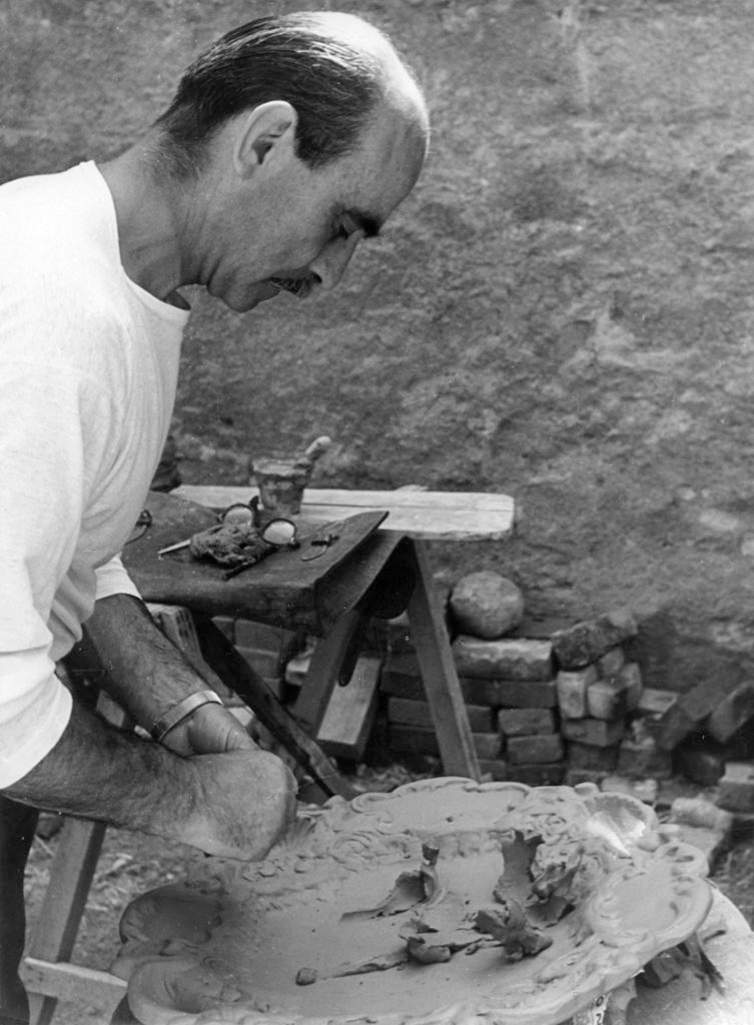

Lucio Fontana (Rosario, 1899 - Comabbio, 1968), although internationally recognized primarily for his Cuts (or, rather, Waits), actually devoted a preponderant part of his creative activity to ceramics, a medium of expression that he radically transformed over the course of more than four decades. Fontana’s ceramic production (explored in depth for the first time in the exhibition Mani-Fattura: the Ceramics of Lucio Fontana, at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice from October 11, 2025 to March 2, 2026, curated by Sharon Hecker) numbers more than two thousand pieces and accompanies Fontana throughout his career, from his early experiences in Argentina to the economic boom years in Italy. Clay, with its infinite material possibilities, became for the artist a privileged ground for continuous experimentation.

Although Fontana worked intensively with clay, he defined himself primarily as a sculptor, not a ceramist, as early as 1939. This positioning reflected his intent to overcome the historical marginalization of ceramics, traditionally associated with craft rather than “pure” art. His ceramic work ranges from the minute to the monumental and embraces a wide range of subjects: human figures, sea creatures, harlequins, warriors, sacred themes (such as the Crucifix and Madonna and Child series) and abstract forms. This extraordinary capacity for mutation and fluidity between different styles, from the archaic figurative to the almost Baroque dynamism of his early Spatialism, was not accidental, but, according to Sharon Hecker, can be read as a profound strategy of psychological resistance forged by the trauma he suffered on the battlefields during World War I (he was one of the celebrated “boys of ’99”). Clay, with its centuries-old rules and inherently collaborative working process (particularly with the Mazzotti workshop in Albisola), provided Fontana with a foundation of stability and grounding, counterbalancing the excitement generated by the unpredictability of fire. Ceramics thus became, as Duilio Morosini called it, his “other half” or “second soul,” an essential and generative element for his artistic vision. It was through this medium that Fontana could explore in a more intimate and tactile way the concept of space, time and matter, anticipating and concretizing the ideas of his Spatial Concepts. Here are the reasons why Lucio Fontana is a ceramic genius.

Lucio Fontana’s decision to devote himself to art and, in particular, to modeling clay, was deeply influenced by thetraumatic experience of World War I, as he himself acknowledged. Enlisted as a volunteer, Fontana experienced the horror of the battlefields on the Karst for two years and brought back a lasting sense of torment. Upon his return to Argentina in 1922, it was the need to express the “reactions” caused by the war that pushed him toward art. Clay, with its immediate materiality, became almost a lifeline, so much so that in 1947, writing to his friend Tullio d’Albisola, he considered it a crucial choice, placed between “suicide and travel,” hoping it would give him the “feeling of still being a living man.”

His first stated ceramic work, the Charleston Dancer (1926), although made of painted plaster to simulate polished ceramics, underscores the symbolic importance the artist attached to this material early on. Following the example of works such as Black Figures (1931), Fontana initiated research based on archaic, organic, and “primitive” figures in terracotta and plaster, marking abreak with the academic sculpture and marble working learned from his father and master Adolfo Wildt. The abandonment of classical sculpture in favor of modeling allowed a more intuitive and expressive gesture. His early terracottas, characterized by an austere form, often unglazed and fired at low temperatures, already showed a dynamic between figuration and abstraction. This approach responded to the postwar desire for renewal, and clay provided the perfect medium to shape this new artistic horizon.

A pillar of Fontana’s ceramic genius was his close, long-lasting and complex collaboration with the ceramic district of Albissola, particularly with the Mazzotti family workshop, where the artist worked assiduously for more than two decades beginning in 1936. This was not a simple outsourcing of production: scholar Luca Bochiccio explained that the collaboration with the factory founded by Giuseppe Mazzotti found continuity over time due to an intricate complex of artistic, human, cultural and technical-processual reasons (“The reasons for such predominance,” Bochicchio wrote, “should not only be found in the superiority technical and productive superiority of Mazzotti, historically recognized and documented, over other artisan manufactures in the area, since it is necessary, in fact, to consider and reconstruct the terms of human relations, of the ideological, poetic and experimental assonance that characterized the relationship between artist and craftsman.”) The subsequent meeting with Tullio d’Albisola (Tullio Mazzotti), a Futurist ceramist, artist and peer, proved crucial, as Tullio fostered an environment open to dialogue, serving as an accomplice and mentor in Fontana’s journey as a ceramic sculptor.

In the mid-1930s, Fontana’s ceramic production underwent a radical transformation, moving from the austere terracottas of the early period to a phase characterized by an explosion of life, with works inspired by marine flora and fauna, often vibrantly glazed. This period, which included his sojourn at the Manufacture de Sèvres in 1937, was summarized by the artist as the creation of “a whole petrified and shining aquarium.”

Fontana explored the fusion of abstraction and realism, working on different scales (from monumental to small) and varied textures. The artist drew on a repertoire of aquatic subjects, producing sculptures such as the famous Crocodile (1936-1937) and Sea Horses (1936), often presented in pairs to highlight affinities and differences, a play of variation that also manifested itself in the use of divergent glazes, such as deep black and vivid pink. In still lifes, Fontana subverted chromatic expectations: a white pear with a gold stem and a shiny gold banana created an intentional dissonance between organic form and artificial surface, intensifying the dialogue between otherness and identity. This tendency toward repetition, splitting and formal variation was not only an aesthetic device, but served as a psychological strategy to deal with the weight of his wartime experiences. Fontana’s technical mastery also allowed the fusion of nature and art: witness Conchiglie (Mare) (1935-1936), a refractory clay work in which the artist appreciated the incorporation of real moss into the surface, creating an effect of spontaneous environmental integration.

The great revolution that Fontana introduced into ceramics consisted above all in making ceramics the ideal medium for bridging synthesizing the artistic experiences that marked his evolution, particularly the Futurist and Baroque legacies, and his founding theory of Spatialism: in this project, movement became the real key to revolution. Working in the Milan of Futurism and in close contact with Tullio d’Albisola, a Futurist ceramist, Fontana approached the material with a vivid urgency. Malleable clay perfectly embodied the principles of the Manifiesto blanco (1946), which Fontana signed in Argentina: a key work in which he asserted that matter exists only in movement and that existence, nature and matter are a unity that develops in space and time.

Clay was for Fontana inherently open to the moment and to change. At the same time, his plastic language was nourished by Baroque aesthetics: the swirling movement of the clay, the material excess, and the gestures that created deep folds revealed a Baroque spatiality. This dynamic whimsy and spatial tension was already a prominent theme, distinguishing his Spatialism (which was “inorganic” and pure abstract gesture) from the dynamism of the early Futurists. Fontana constantly sought to transcend art by breaking the two-dimensional limits of the picture. His ceramic sculptures, since the 1930s, were seen as forerunners of an art that favored direct contact with matter. His works, described as “voluntarily anachronistic,” fused the ancient tradition of ceramics with reflections on the infinite, typical of his spatialist thinking. Ceramics allowed Fontana to develop a language that is neither painting nor sculpture, but an art that uses colors through space.

Fontana’s ceramics was also a crucial laboratory for his Spatial Concepts, particularly through the series of holes, a gesture that altered the surface to explore spatial and conceptual dimensions. As early as 1949, Fontana made his first Holes on various surfaces, including clay. The artist regarded these perforations as his “ideas,” an act of “sensuality of gesture” that ripped or cut through the smooth surface of the material. These countless holes, often organized in spirals or constellations, hinted at the atomic aspect of matter and, more generally, at the cosmos and the conquest of space, themes that fascinated him.

This research extended to the imposing spherical terracottas of the Nature series (begun in 1959), which featured deep cuts or holes, inspired by early images of lunar craters. In the ceramic works of the 1950s, such as Spatial Ceramics (1953) or the later Spatial Concepts, Fontana used clay to directly address the fundamentals of modern sculpture, working with rough, massive, irregularly incised masses. The artist intended to go “beyond the wall,” using the holes and cuts not as mere decoration, but as effects that activated new spaces and invited the viewer to total emotional participation. The gesture of drilling, together with tearing or engraving, transcended the distinction between sculpture and painting, transforming the material into a new expressive dimension that acquired a matrix resonance. Art, in this perspective, was seen as a total presence, a new conversation with matter.

A distinctive feature of Fontana’s ceramic work was his continual return to his origins, his exploration of the very process of making art as a primordial, almost ritualistic gesture. The works entitled Pane (Bread), for example, were rectangular pitted panels that referred not only to food, but also to the “panetto” or “bread” (Albisolese dialect term) that denoted the initial slab of clay, ready to be cut and formed into balls. Similarly, the spherical and ovoid sculptures of Natures (1959-1960) symbolized the beginning and genesis, through such elemental acts as halving, dividing, cutting and piercing, which recalled the image of a cell or atom dividing.

In his later terracotta works, often stripped of glazes and decoration, Fontana intentionally left visible traces of manipulation: fingerprints, twists and incisions. This emphasis on manual gesture and raw materiality was consistent with his rejection of technique and ceramics perceived as fragile or kitsch. Rather, Fontana sought to develop the original condition of humanity by invoking the gestures of our prehistoric ancestors guided by the suggestive power of rhythm. Pottery, with its need to shape, was the perfect vehicle to record the energy of gesture in the moment.

Fontana’s genius was also distinguished in his constant and fruitful integration with the world of architecture and design, elevating ceramics from a pure art object to an essential component of urban fabric and modern furniture. Since the 1930s, Fontana collaborated with key figures such as Luciano Baldessari, Luigi Figini, and Gino Pollini. After World War II, Fontana took an active part in the reconstruction of Milan, a period in which ceramics became the material of choice, and he created permanent installations for public and private buildings in collaboration with architects such as Marco Zanuso and Roberto Menghi: notable are the stoneware friezes on the facade of Via Senato (1947) and the Battaglia bas-relief (1948) in polychrome and fluorescent ceramic for the Arlecchino Cinema.

As a semi-industrial product, ceramics proved to be an ideal complement to modernism. In addition to the pieces installed in situ and friezes (such as those for the railings on Via Lanzone), Fontana devoted himself to mass-produced design: he collaborated with the Gabbianelli company to produce polychrome ceramic handles and, in a significant project with Roberto Menghi for Fontana Arte, he made sculptural pedestals in porcelain stoneware for tables with crystal tops. These works established him as an artist capable of reconciling the authority of the artistic gesture with the functional and mass production requirements, adhering to Gio Ponti’s view that art was neither “pure nor applied,” but simply “art where it is.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.