What reasons still prevent Verona from having its great museum, its Great Castelvecchio, a complex that is finally united in all its parts, and that may yet prove to be, as it was more than fifty years ago, a model capable of innovating, of opening up paths, of enchanting, of astounding? What reasons still stand in the way of the expansion of a museum that is so hungry for space, that feels the need to expand, and that would have at hand the solution that would allow it to finally become an institution adapted to the new parameters of international museography?

Verona has a pearl shining on the right bank of the Adige River: the Museo di Castelvecchio, in addition to the role it plays because of the richness, completeness, and charm of its splendid collection, which includes capidopera by Pisanello, Giovanni Bellini, Filippo Lippi, Crivelli, Mantegna, Rubens, Tintoretto, Tiepolo, and all the greats of Veronese painting of’every century, is to be considered, for the reasons that have been limpidly summarized on these pages by Ilaria Baratta, one of the most brilliant jewels of world museography. It is undeniable that the intervention wanted by the then director Licisco Magagnato, and then designed and completed within the walls of Castelvecchio by Carlo Scarpa between 1958 and 1964, with further work that would later extend until the mid the 1970s, represented an entirely new museographic model that is still studied everywhere, a source of inspiration for legions of architects, a source of wonder for the thousands of visitors who enter the Scaliger fortress every year. Then, over the years, as has happened to all important museums, Castelvecchio has also grown: visitor numbers have grown (which now, every year, surpass the threshold of two hundred thousand by leaps and bounds), collections have grown, and the need to make the museum not only the home of the city’s collections of ancient art, but also a research center, an institute where pages of Veronese art history are still being written, a place of sociability that is open and welcoming to the city’s citizens and guests, and where visitors have the pleasure of returning. The problem, however, is that the enlargement of the museum, which would give concreteness to the coveted Great Castelvecchio project, is currently prevented by the coexistence with the Unified Army Circle, formerly the Officers’ Circle, which occupies an area of two thousand square meters (which becomes more than three thousand if the exteriors are also considered) inside the Scaliger fortress. And it is precisely this area that would allow the museum to expand and finally provide those services that it is currently unable to fulfill.

A historical premise is needed, meanwhile. The Officers’ Club has been based in Castelvecchio since 1927, when the State Property Office, at that time the owner of the fortress on the Adige River, granted the Army the use of the western wing so that it could install its club there, although the plan to turn Castelvecchio into a museum was already in full swing, after the divestment of the barracks that had been based in the castle. Indeed: the museum had already been opened, on April 25, 1926. Only two years later, however, the State Property Office would cede Castelvecchio in perpetual use to the municipality for use as the headquarters of the Civic Museum. In the deed of cession, dated February 23, 1928, one can read a detail of no small importance: the cession also included “the premises [...] currently occupied by the Military Club and annexed accessories and of the Presidiary Library, granted for use by the contract December 14, 1927 stipulated at the State Property Office of Verona for the duration of 29 years from January 1, 1927.” The occupation by the armed forces was to cease “as soon as the Municipality of Verona makes available to the Military Administration other premises suitable for the same purpose.”

From the beginning, therefore, it was established that the Circle was to have only temporary headquarters in Castelvecchio. A location to be vacated as soon as the City of Verona had found a more suitable venue for the army officers. As often happens in Italy, however, what was to be temporary became permanent: we can spare the reader all the bureaucratic delays that have intervened over the decades and all the swamping that the issue, which has been talked about for decades, has experienced throughout history, but it will be interesting nonetheless to point out that the coexistence between the Museum and the Circle continued its course without regulation until 1983, the year in which a “report of reconnaissance and handover” assigned to the Ministry of Defense the area occupied by the Circle, which, moreover, in 2010 was recognized as an articulation of the ministry itself, so much so that, in 2016, the transfer from the State Property Office to the Municipality of Verona of the full ownership of the Castelvecchio complex concerned only the part used as a museum, while the same year the area occupied by the Circle was handed over by the State Property Office to the Ministry of Defense. Administrative problems, however, matter relatively: there is no bureaucratic issue that, however long-standing and intricate, cannot be resolved to the benefit of all. And that of Castelvecchio is exactly a case of now-forced coexistence that, should it be dissolved, would benefit the interests of each of the parties: of the Museum, which would finally have the space to expand. Of the Circle, which would have a new and modern headquarters, moreover already identified. Of the city, which could relaunch its museum. Of the guests, who would be empowered to visit a modern museum that meets those minimum requirements of participation, accessibility, sustainability, and retention capacity that every institution should guarantee.

It has always been difficult, as is obvious to imagine, to intervene on Castelvecchio: any architect in charge of rearranging the halls would not dare to touch Carlo Scarpa’s layout. It is not a relic, of course, and it is not impossible to update it. But neither is it just another exhibit. To radically alter Carlo Scarpa’s rooms would be like thinking of changing the face of Pisanello’s Madonna of the Quail . This installation is a work of art, an exemplary gesture of respect and knowledge towards the ancient fortress, a fundamental historical document, an itinerary based on the idea of the co-presence of past, present and future, an itinerary in which it almost seems as if you can feel the breath of the works on your neck. Conversely, the last part of the itinerary, where the Boggian Room is located, is where Carlo Scarpa’s intervention was least incisive, and where therefore more extensive could be an eventual modernization of the displays. Without the museum remaining a prisoner of itself.

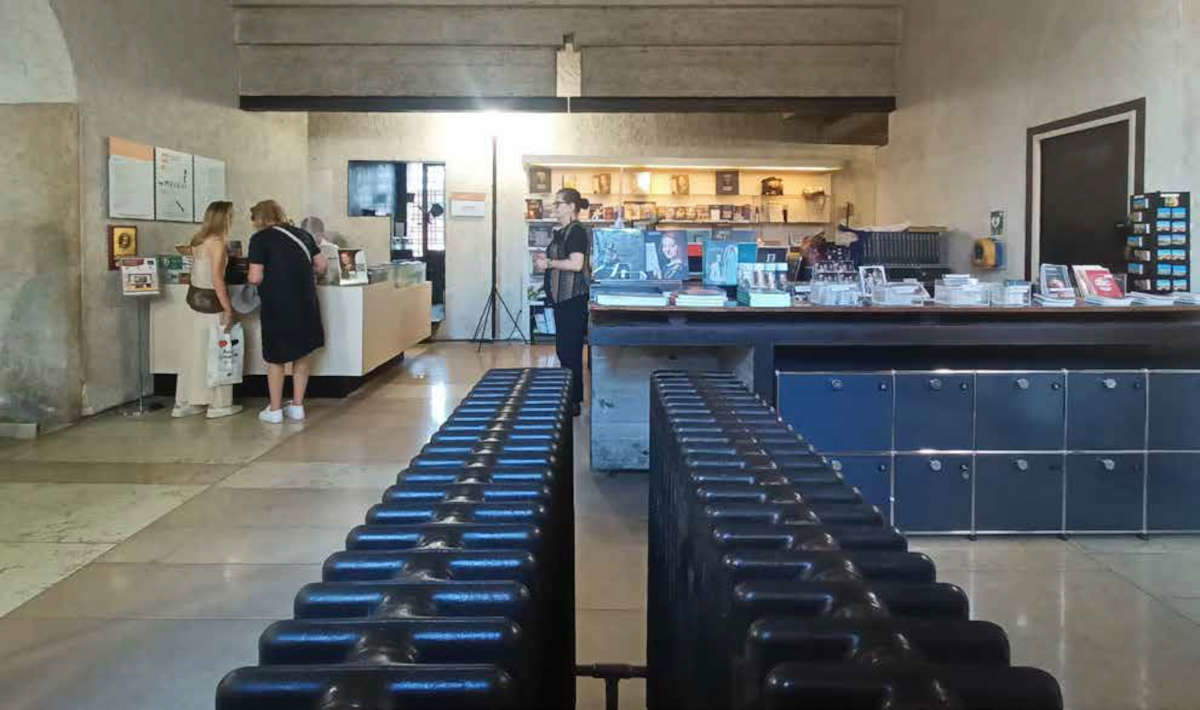

At present, the Boggian Hall is used for temporary exhibitions. I still remember the last major exhibition I visited in this space, the one on 16th-century Veronese painting, which was held between 2018 and 2019 and of which I still have a pleasant and vivid memory, because it was an exhibition of great enjoyment and of even more sum quality, and because my review was published in the first issue of the paper edition of Finestre Sull’Arte. Should the area currently occupied by the army be vacated, the Boggian Room could be used for the exhibition of Veronese painting of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which now, for reasons of space, is largely confined to storage rooms, while the new wing could house a salon for temporary exhibitions, twin to the Boggian. But it is not only exhibition space that the Castelvecchio Museum needs. Anyone who has visited it knows this well: the book and souvenir store is skimpy and forced to cohabit with the ticket office and a tiny array of lockers passed off as a checkroom (expansion would instead allow for a meaningful bookshop that rivals that of major museums), visitors are given only one restroom in the entire museum, there is no café, and there is no restaurant (which to many might certainly seem like overkill, but in a museum where one can nimbly spend a half-day they would be no small convenience). In addition, the Art Library, one of the most important specialized library collections in the entire Veneto region, attended by over three thousand people a year, is now crammed into just one hundred and forty square meters: it is, in essence, the size of a classically cut apartment.

There is already a plan of how Castelvecchio could be enlarged should the Unified Circle wing come into the museum’s availability. And it is, moreover, a project that is already quite dated: it is the result of a working group assembled by the Friends of the Civic Art Museums of Verona and flowed in 2017 into a publication, Fantasie per Castelvecchio, which included a proposal for the expansion. The final part of the current itinerary would thus become a substantial section on the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which would extend the current one, currently housed in only two rooms out of the more than thirty that make up today’s tour itinerary (it is as if the present section would get three or four additional rooms). The rooms where the staff offices are now housed (which would be moved to the new wing, inside spaces that would almost double in size) would be partly used as a section devoted to the telling of the history of Castelvecchio (absent today), and partly would be allocated to theexpansion of the reception area, with the new bookshop, with toilets currently reserved for staff that would be made available to the public, with the opening of a nursery, with a checkroom that is worthy of the name. And in the Tower of the Keep, space would be obtained to display Cangrande’s fabrics, a rare collection of fourteenth-century textiles unearthed in 1921. In the two thousand more square meters that the museum could obtain, the new exhibition hall would be opened instead (which would occupy the current hall of the Circle), there would be new classrooms for teaching, the Numismatic Cabinet, which now can only count on cramped spaces, would be secured theopening of a café-restaurant taking advantage of the facilities of the Circle’s current one, staff offices would be installed that would accommodate twenty staff members, and then again there would be the maintenance laboratory for the works, a four-hundred-square-meter storage room, the teaching room, and the new Art Library. And finally, the path of the walkways, which now stops where the museum meets the Circle wing, could be completed.

This is, of course, a proposal: it is not necessarily the only one, nor is it the best. And even the costs for now have only been estimated. Any proposal, however, can only go through the liberation of the wing now occupied by the military. And without this will, without a shared solution, one cannot proceed further at the moment. No one, of course, dreams of leaving the Circle in the middle of the road. There are already proposals on the table for a new home, alternately identified in Palazzo Carli, which is, moreover, right across the street from Castelvecchio, or in the former military hospital of Santo Spirito, for which in 2017 the Friends of the Civic Museums of Verona commissioned a project for a new home for the Unified Circle, later donated to the Army. There are no valid reasons for preventing the expansion of the museum: there are no historical reasons (since 1927 the presence of the Circle in Castelvecchio had been intended to be temporary), no cultural reasons (Castelvecchio needs to expand, Verona needs a large museum that conforms to what modernity demands), no practical reasons (moving the Circle would be mutually beneficial). Those who so far have been strenuously defending the presence of the Circle in Castelvecchio have done so just out of habit, out of nostalgia (a move, after all, is always a matter of emotional ties, but theaffection to a building can also be shown by accepting a choice that is sentimentally difficult for oneself, but which brings benefits to all if it is illuminated by a reasoning light) or for reasons of impalpable and impractical solidarity with the armed forces: well, perhaps it would be a gesture of greater closeness to allow the Circle to count on a new, modern, more suitable venue. No reason of those who defend the current presence of the Circle in Castelvecchio would withstand thirty seconds of rational analysis. There are, after all, also many military personnel, officers and frequenters of the Circle who, especially in 2021, when the Great Castelvecchio debate experienced a moment of strong popularity (it was election time), intervened in the press to support the Castelvecchio expansion project and to advocate the relocation of the Circle.

The story, moreover, also has a precedent, that of Palazzo Barberini in Rome, which had the same coexistence problem as Castelvecchio: first, the Ministry of Defense moved the Officers’ Circle to the Savorgnan di Brazzà building, a location close to Palazzo Barberini and more suitable, and then, in 2015, signed an agreement with the Ministry of Culture to also cede to the museum the rooms of thesouth wing that until then had been in the availability of the armed forces, and four years later it was possible to open in those rooms new sections of the exhibition itinerary and expand the spaces dedicated to temporary exhibitions. There is, therefore, no situation that cannot be resolved to the profitable satisfaction of all parties: the Civic Alliance for a Great Castelvecchio, a group that was formed six years ago and brings together professionals, organizations and associations in Verona to give concrete form to the project, continues to animate the discussion to ensure that the most natural and obvious solution to the matter can be reached. It is not a matter of “if”: it is only a matter of time, and Verona will have its Great Castelvecchio. The hope is only that the wait will be as short as possible, because we are certain that the museum will not be stifled, and that Verona will know how to choose the best path, the path that leads to a modern museum, capable of offering its visitors services and spaces suited to an institution that has entered the third millennium, the road that leads to an idea of a city that is aware of its heritage, that knows how to dialogue with its fathers, that knows how to polish its jewels without distorting them but, on the contrary, interpreting at best the spirit of those who made Castelvecchio an example, a model, a laboratory. It is time to start a new season for Castelvecchio, one that takes up the legacy of Carlo Scarpa, applies his own principles of active care for heritage and makes the museum live in the present.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.