The restoration of Guido Reni’s Crucifixion placed on the high altar of the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Lucina in Rome was presented on September 13. The year-long intervention was conducted by Davide Rigaglia with Valentina Romè and is well illustrated in the bilingual volume published by Gangemi , "Il restauro della Crocifissione di Guido Reni nella Basilica di San Lorenzo in Lucina / The restoration of Guido Reni’s Crucifixion in the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Lucina," edited by Monsignor Daniele Micheletti and Rigaglia himself (92 pages., 24 euros).

The publication opens with a historical-theological foreword by Micheletti, parish priest of the Basilica, who invites us to “look” at the altarpiece with new eyes other than as a mere, albeit supreme, masterpiece of art. This is followed, by Sergio Guarino, by the art-historical record of the painting, described as “famous and secluded” because relatively little space is devoted to it in the albeit vast and impressive bibliography on the “divine Guido.” Reni, who depicted the subject of the Crucifixion several times in his intense career, made this version in Bologna around 1637-1638, commissioned by the noble Angelelli family. Due to tragic events that marked the latter, namely the murders, twenty years apart, of Marquis Andrea and his son Francesco, the canvas wandered between the Emilian capital and Rome. It found its final location in 1699 by the testamentary will of the last owner Cristiana Duglioli Angelelli, Andrea’s widow.

In the volume, the description of the conservation and restoration events is entrusted to Rigaglia and Romè. They are also the ones who give an account of the accurate diagnostic investigations, together with those who carried them out in person: Valeria Di Tullio, Annalaura Casanova Municchia, Giorgia Sciutto and Claudio Seccaroni. These analyses made it possible to learn unpublished details about the support (a single linen cloth), the execution technique and the constituent materials used by the Bolognese artist, and to identify the resins used for the final varnish previously applied.

All this made it possible to best guide “the removal of the pictorial additions and the oxidized and chromatically altered protective layers that interfered with the correct reading of the pictorial text.” Ultimately, the “chromatic and material identity of each brushstroke” and “the aesthetic and plastic values sought and desired by the artist” were recovered.

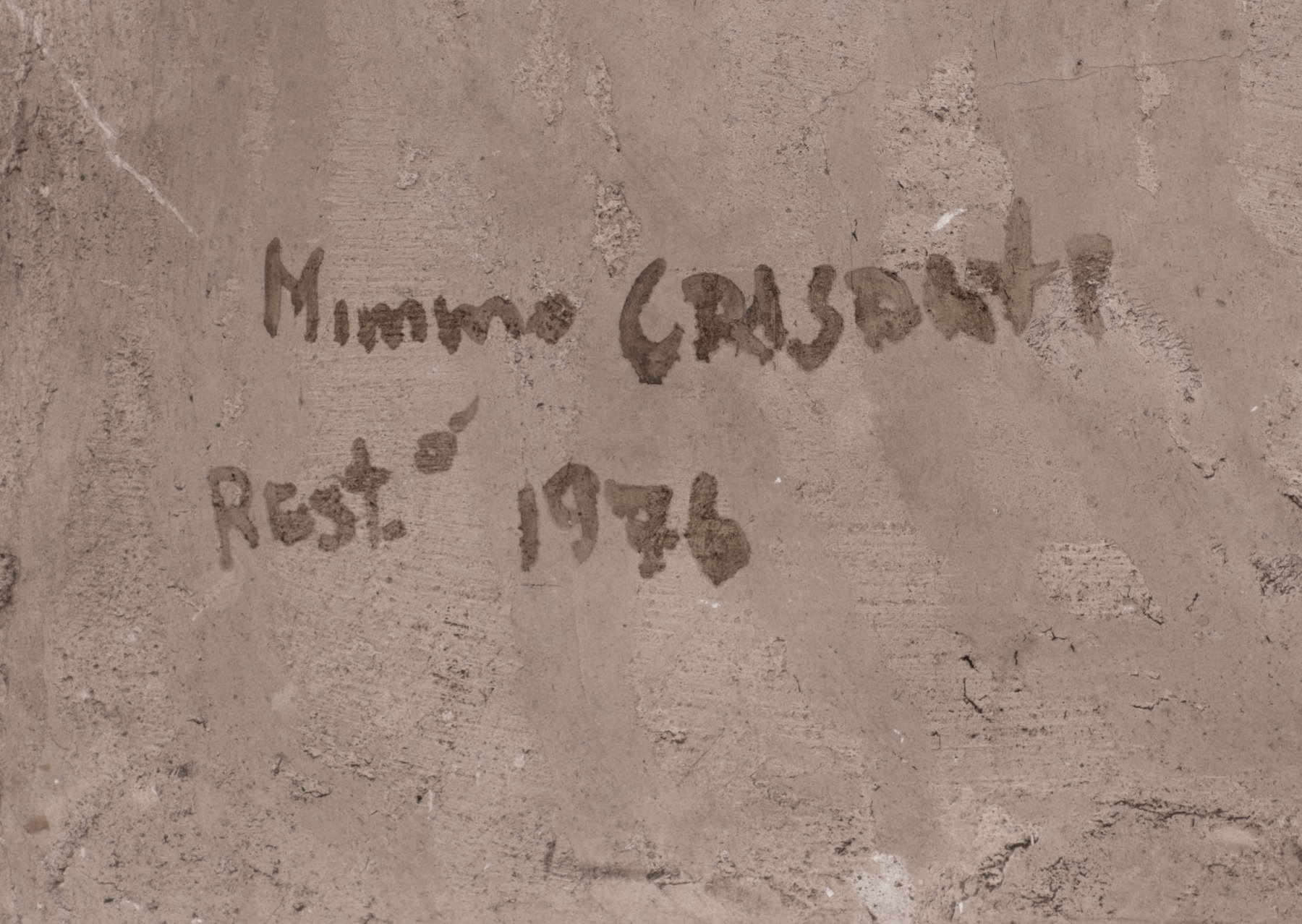

One of the published curiosities is that as soon as the painting was removed from the wall, the signature and date of the last intervention appeared on the plaster behind it: "Mimmo Crisanti rest.ò 1976.“ Ermete Domenico Crisanti, a Roman restorer, has long since passed away, but thanks to the personal materials still kept by his daughter, tracked down for the occasion, it was possible to derive more information about that work of his: apparently the ”only one documented" on Reni’s Crucifixion, according to the writer of the volume.

A parallel research on San Lorenzo in Lucina that I carried out at the Photographic Archive of the former Soprintendenza per i Beni Artistici e Storici di Roma, having as its specific object of study the sculptural decoration of the chapel of San Carlo Borromeo that once belonged to the Pasqualoni family, proved fruitless in that regard. The consultations, on the other hand, returned documentation of some restoration work on Reni’s altarpiece prior to that of Crisanti.

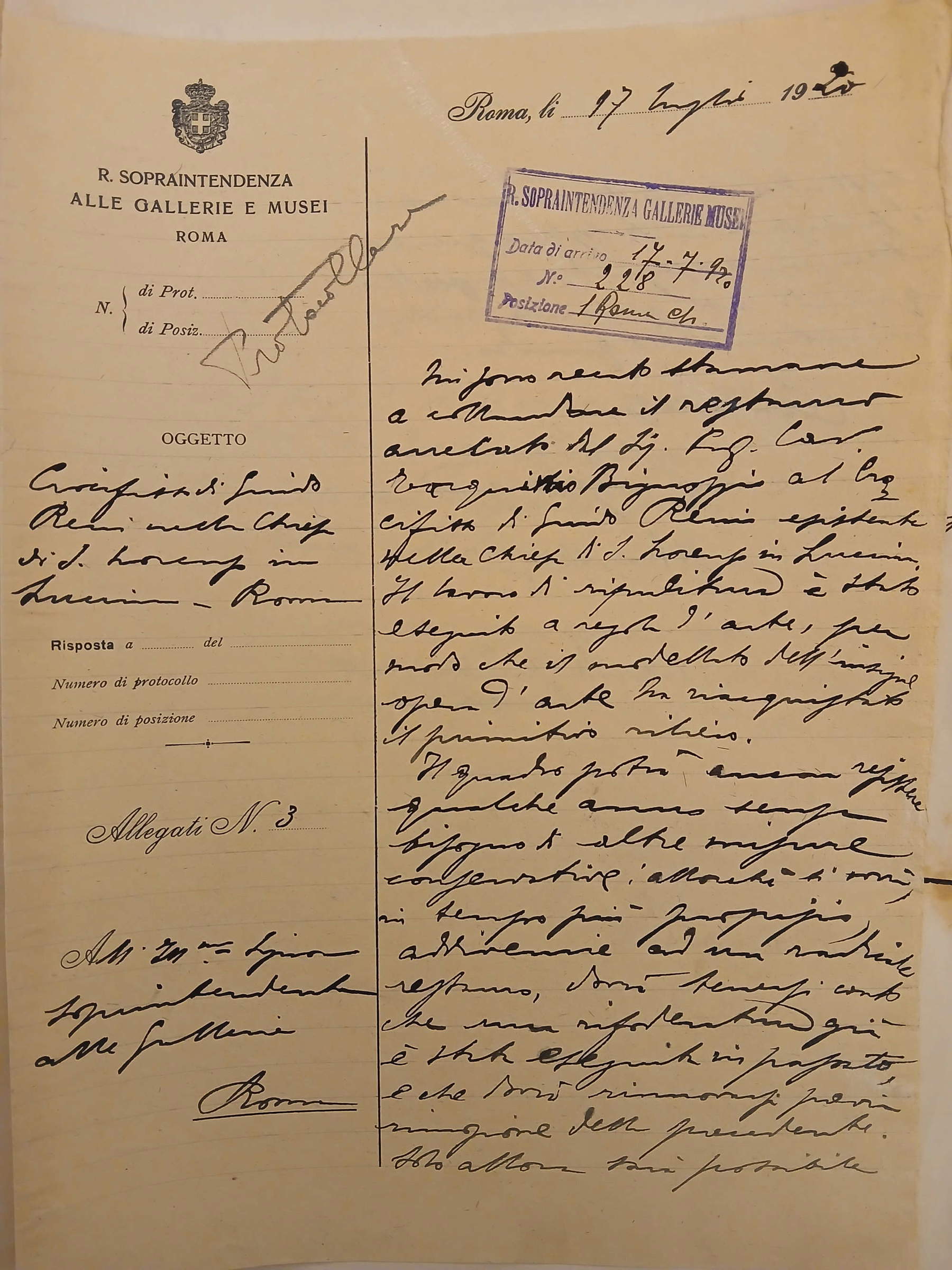

This of 1976, we learn meanwhile from a letter addressed to the Soprintendenza, had been invoked as early as February 1972 by the Basilica’s parish priest, who reported “several foreign scholars, who had come as tourists” who allegedly confirmed his concerns about the Crucifix’s state of health.

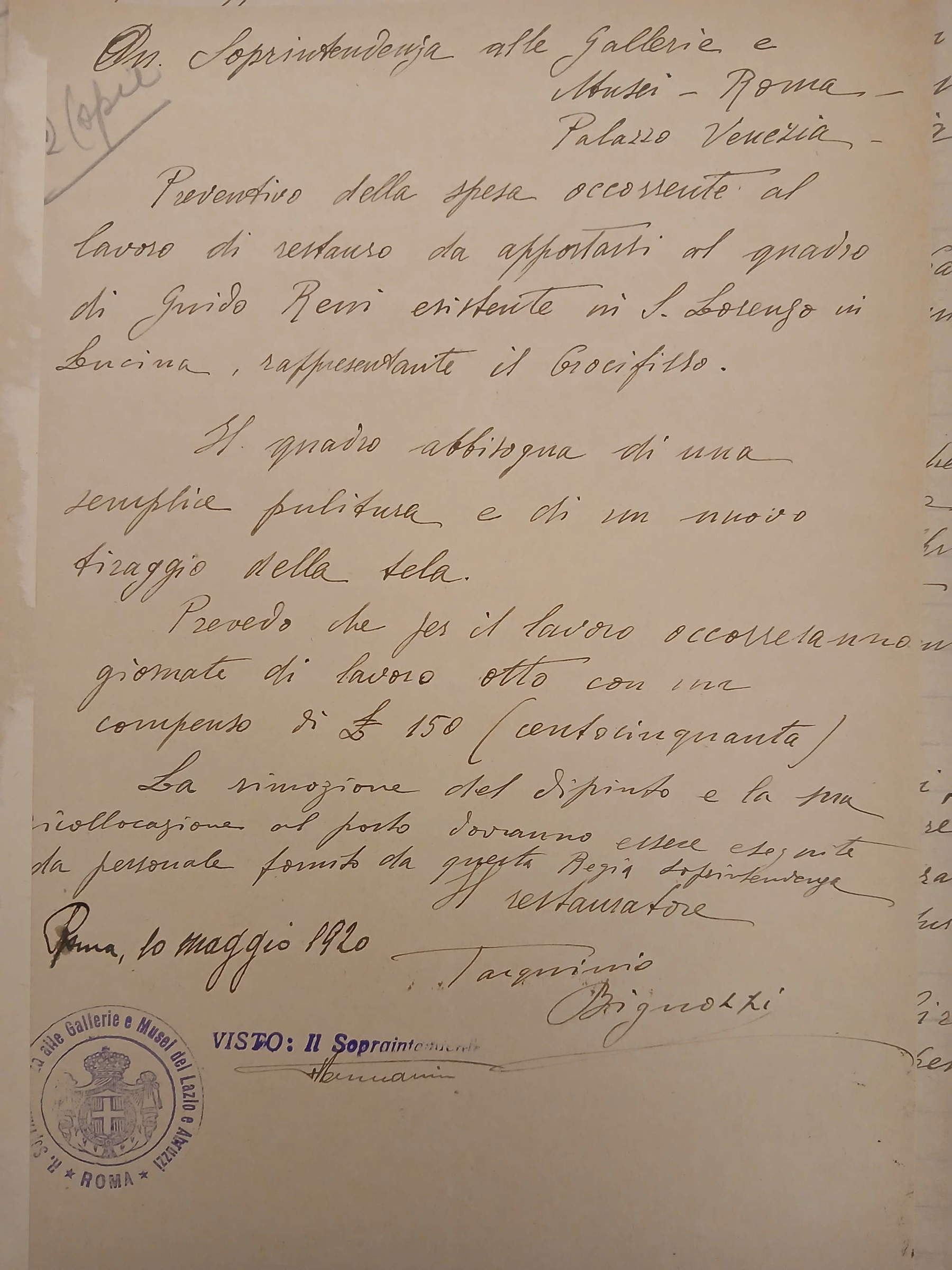

Going backwards, on November 25, 1937, restorer Carlo Matteucci had submitted an estimate to the then Royal Superintendency of the Galleries of Rome. The painting was found to be “a little deteriorated” and in the lower part the “slowed” canvas had completely detached from the frame, “making bags.” In this same area, on either side of the Christ, there were two large “dents.” The whole painting was “parched,” “clouded by centuries-old dust and candle smoke so that the painting was veiled and cloudy,” with several lifts and falls of color. For a job “done properly,” Matteucci demanded a fee of 2,200 liras, which did not take long to be approved, but was reduced to 2,000.

In a couple of months the operations, described in the final report of February 9, 1938, had already been completed. First, the “paint oxide” that altered the legibility of the pictorial text had been “removed. ”Two deep pits on the canvas with abrasion of color, probably due to badly supported ladders“ and located in ”vital parts“ of the painting had been repaired ”with reinforcements to the canvas and perfect resumption of color.“ Prior to the final varnishing, the ”various holes“ produced to the frame were repaired in order to apply hangings to it, and a reinforcement was applied to the same in the center, finally obtaining ”the perfect distension of the canvas."

This of 1937-1938 is not the only documented restoration besides Crisanti’s, and it is surprising that yet another had preceded Matteucci’s work by only seventeen years. It was, however, “a simple cleaning and a new draughting of the canvas,” as projected in the May 10, 1920 estimate of restorer Tarquinio Bignozzi, who, at the same time, would also take charge for a more complex intervention of Carlo Saraceni’s altarpiece in the chapel of St. Charles Borromeo.

The operations were carried out in record time, unthinkable today: on July 17 the Crucifix was returned by Bignozzi after only eight days of work, including holidays, for the fee of 150 liras (for Saraceni’s canvas it took three months, and 1,150 liras). In the inspection of the restoration Achille Bertini Calosso, at that time inspector of the Soprintendenza, predicted that the painting could “still resist a few years without the need for other conservation measures,” and that a more “radical” intervention could be postponed to “a more propitious time.”

There are no traces of further restoration after 1896, the date from which the historical documentation of the Photographic Archive starts, where, in addition to what has been mentioned so far, some shots related to Crisanti’s restoration are preserved.

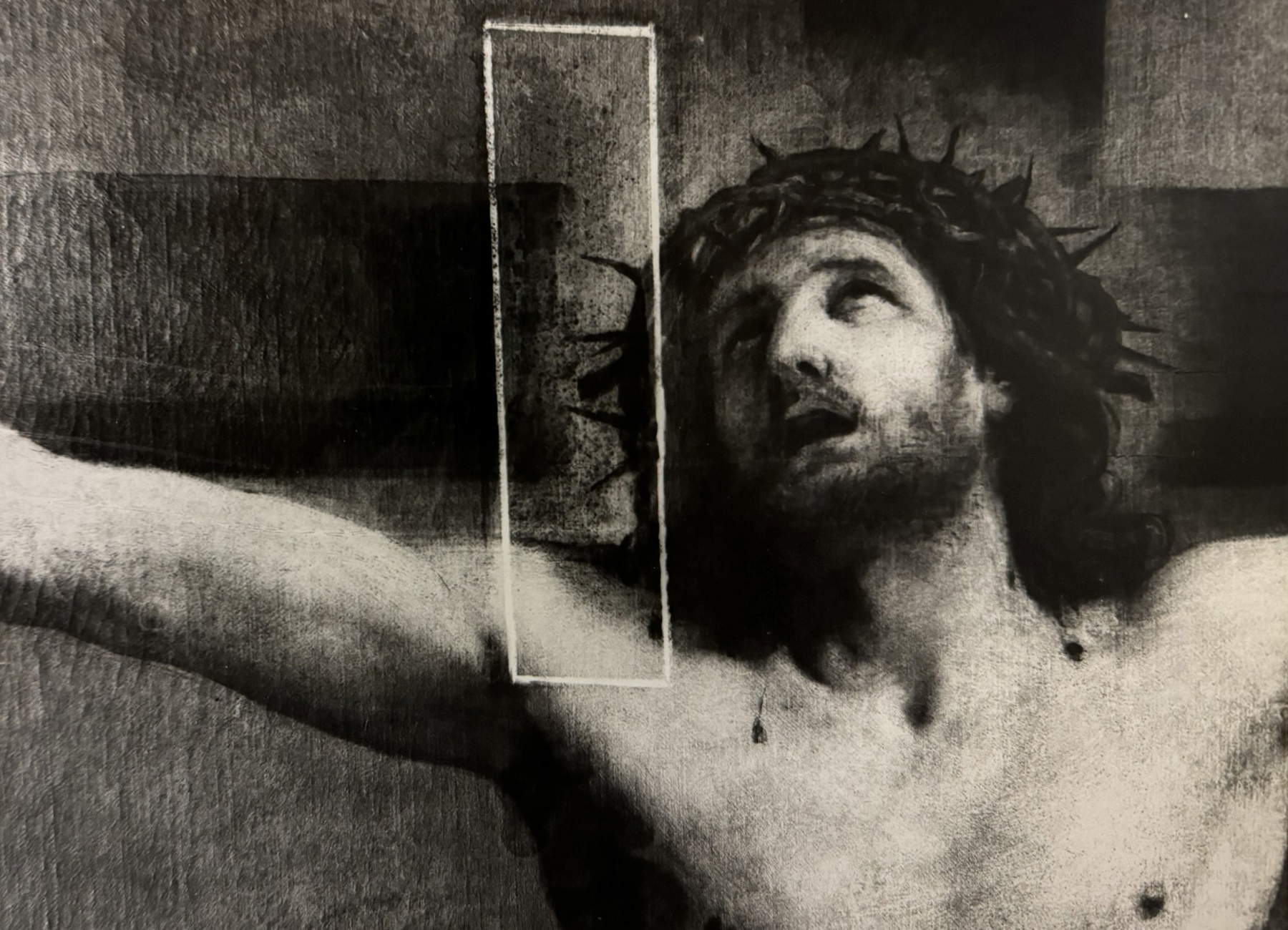

With regard to the reproductions available more generally, one from the Alinari Archives(ADA-F-004822-0000) made by Domenico Anderson between 1891 and 1899 is particularly noteworthy, as can be seen by comparing the well-known photographer’s catalogs relating to those years (shot 4822 is absent in the first and appears for the first time in the second catalog). It is thanks to this image that Rigaglia and Romè were able to attest how some gaps in the painting, specifically the one in correspondence to Christ’s chest, were most likely generated by anthropogenic causes at a time before the end of the 19th century. In addition to compensating for these areas, today’s intervention attempted to bring the deformation of the textile support back into correspondence with them, to the extent possible due to the double lining applied by Crisanti.

A further curiosity that the Photographic Archive restores to us is the “very ugly curtain” that covered the work before October 1933, as reflected in the request to remove it made on this date by Federico Hermanin to the parish priest of San Lorenzo in Lucina. The drapery, wrote the then superintendent, calling it a real “smut,” “besides removing the very important painting from the gaze of visitors, disfigures the aesthetic effect of the magnificent altar, the work of Rinaldi.” It is glimpsed in an Alinari/Anderson photograph from before 1891(ADA-F-000114-0000), at that time appropriately retracted on the sides, perhaps with the very occasion of the shot.

A final note. After the creation of the so-called holistic Superintendencies and a period of administrative transition in which it was not usable by outside users, the Photographic Archive, which since 2019 has been in handover to the newly established VIVE (Vittoriano and Palazzo Venezia), is once again accessible thanks to new agreements between the latter and the current Superintendencies. At present, it is open for two hours a week, subject to the availability of two officials: an inadequate limit, one would say, for the consultation of a huge patrimony of materials essential for scholars and technicians. As for the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Lucina, the chapels on the left side are being restored, and who knows what other new things may be in store for the construction site opened last June.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.