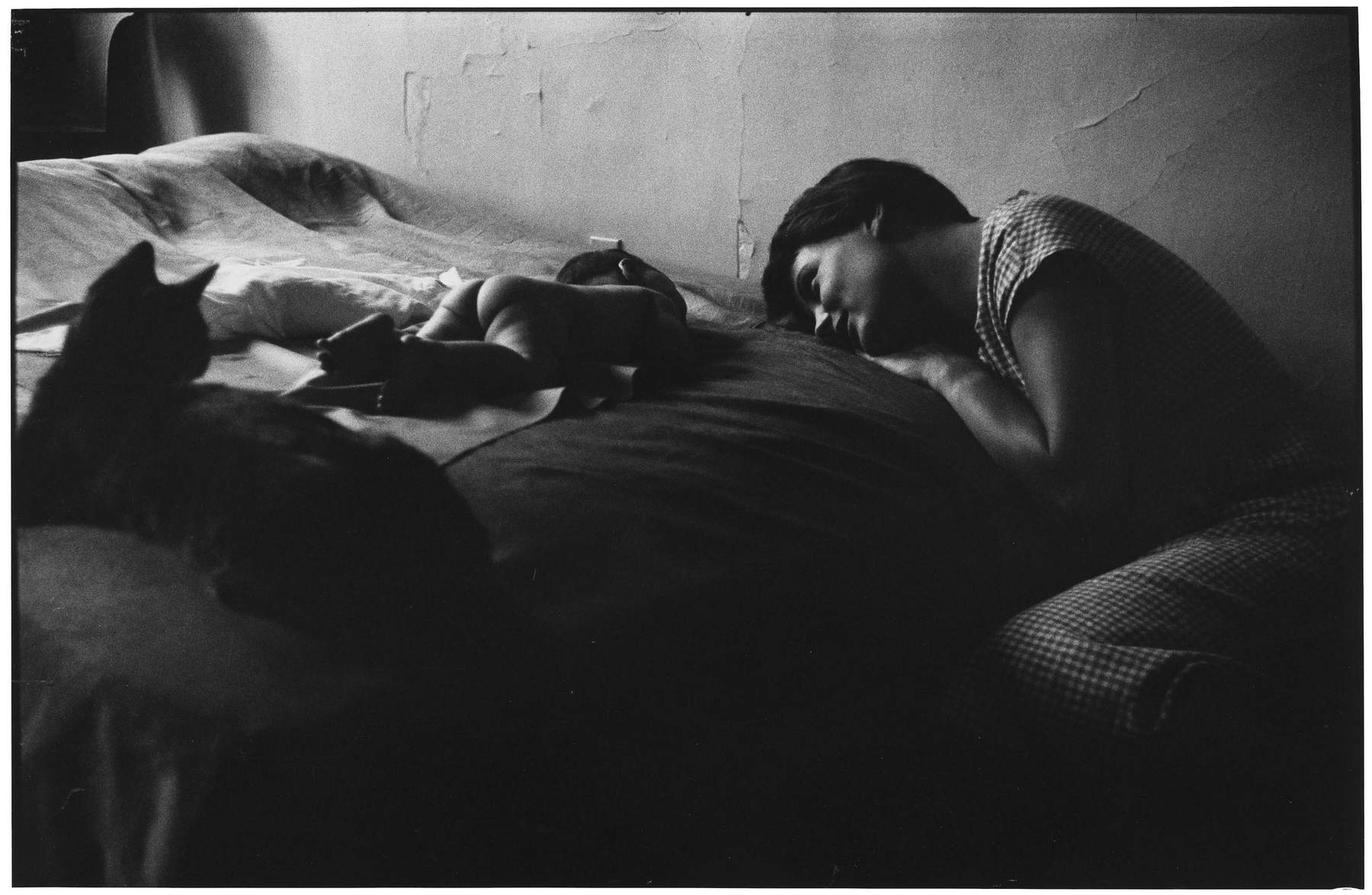

As my computer background I have a picture of Elliott Erwitt. I didn’t put a picture of my daughter, but I put a picture of another daughter and another mother. There is also a cat in it, and I don’t like cats. But this is the sweetest picture I have ever seen and it tells, better than any other picture I know, about motherhood.

The newborn baby girl is sleeping comfortably on a large mattress. The mother is curled up beside her on the floor, looking down at her. There is in this gaze all the dedication and unconditional love that a woman assures her child from the very moment it is born, but also all the thoughts about the future, the worries, the joys of one who has already experienced life and is looking at the one who has just entered it. And in the face of such a wonderful, all-encompassing gaze, we have no choice but to be the cat silently enjoying the scene.

The photo is Family, also known as Mother and child, and thanks to the proofs that Magnum has made accessible we can peek behind the scenes of this scene. The year is 1953, Elliott Erwitt (who passed away in New York City at age 95 on Nov. 30) is a loving father starting a family in his New York home and documenting it with his camera. The child pictured in the photo is Ellen, his first daughter, and the mother is Lucienne, his first wife. That photo, among the many taken in that sequence, had the power that only great images have: it stepped out of the family context, took on a universal meaning, and as Erwitt said, after more than sixty years “it is still strong.”

It is amazing that a snapshot of such sweetness came out of the gaze of the most ironic and irreverent photographer the textbooks remember. A man capable of recounting the great events of the twentieth century, and with the same attention telling of dogs, taking photos on commission, but also on the street on a walk in Central Park, and capturing in every context those images that have become, truly, iconic. To photography he has dedicated his entire life. “I am a professional photographer with an important hobby: photography”: he loved to introduce himself in this way.

He photographed Fidel Castro and Che Guevara in 1964 after the Cuban revolution, only to return immediately when the United States and Cuba had decided to normalize relations in 2015. He photographed Marylin Monroe in her prime, and of her he said “there is nothing more drastic than ending a career with death.”

He was a photographer who claimed to be “full of popes and presidents” and took, almost by accident, one of the most significant photos of the tensions between Russia and the United States, the one of Richard Nixon pointing a finger at Nikita Khrushchev’s chest. It was 1959, and Elliott was at the opening of the American National Exhibition at Gorky Park in Moscow, on an advertising assignment for Westinghouse refrigerators, and he found himself at the right time in the right place. The two appeared to be engaged in a heated debate as they visited a model of a typical American kitchen designed to showcase the comforts of the American lifestyle, and this photo has since earned the name The Kitchen Debate.

He had also been to Italy several times, for work and to meet his friend Gianni Berengo Gardin, with whom he shared many artistic choices: that of black and white as the main (if not exclusive) language of photography, that of the telling of reality done with an immediate gaze, a vision of the world simple, but at the same time rich in deep nuances. A Silver Salts Friendship is the wonderful title of an exhibition, and of a book that chronicles them together (published by Contrasto).

Elliott

Elliott Elliott

ElliottEvident in each of his images is an incredible ability to capture the moment, the result of teaching that decisive instant theorized by Henri Cartier-Bresson and the very Magnum founded by HCB he had joined at the age of twenty-five and later became its president. But Erwitt did something more; it seemed almost as if as he passed, life bent to the will to unearth a conjunction of surreal, and ironic, elements. Famous is the photo taken at the Prado Museum in Madrid in 1995 where in front of Goya’s twin paintings the Maya Desnuda and the Maya Vestida there are seven men looking at the former, and one woman looking at the latter. An image so current that it is still being repurposed today when we talk about the attitude of genders.

He is also behind the most famous photo of all postcards of Provence Boy, bicycle & baguette from 1955. He behind a the couple kissing reflected in the car mirror, taken in California in 1956 and which also had remained unnoticed among the auditions for more than 25 years.

But he was not just a postcard photographer; indeed, his emergence as a photographer saw him documenting major changes in postwar American society, still marked by great social inequality, and racial segregation that was still legal. The photo of the black child holding a gun to his temple while smiling heartily, taken in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1950, is famous. It is a controversial photo: funny but also disturbing, and like all of Erwitt’s photos it makes people think.

Success, however, came in the scraps of time between various commissioned projects, the ones that-he declared unfiltered-allowed him to pay the bills and support six children (by four wives) and nine grandchildren. “Success is the freedom to do what you feel like at a certain time,” he declared, and he also expressed his freedom by walking around New York City with a trumpet attached to his walking stick, blowing it suddenly, triggering surprise in people and their animals, whom he then photographed. So much for “say cheese.”

Tireless, they say of all artists who pass the age of retirement. But he was tireless for real. He took almost a million photos, as only those who use digital today and are not afraid to waste film do. In 2021 he published Found not lost(published in Italy by Contrasto under the title of Found photographs, not lost) the result of a titanic feat: rearranging each of his photos in search of a new overall reading. “It takes a good dose of wisdom, irony and courage to revisit a heritage of images as impressive as his, which few other artists would venture to tackle,” writes Vaughn Wallace in the introduction.

Ironic and self-deprecating, as in his self-portraits: in an Afghan suit or a blond wig, or as a clown and even as in a mug shot with the name “Jesus.” In photographs as in words, “Nothing is serious and everything is. I take not being serious seriously.” It is said that great irony comes out of great sorrow. But we cannot know if that was true for Elliott, who about his long life has always been very private. The son of Russian-born Jewish parents, he was born in Paris in 1928 and spent his childhood in Milan trying to escape the racial laws that led his family to flee to the United States in 1939. His longest public narrative is a documentary filmed in 2019 by his late assistant Adriana Lopez Sanfeliu (from which many of the quotations in this text are taken) in which Elliott continually balances between his eagerness to tell his story and his proverbial reserve, and in conclusion declares “Silence sounds good” (in the original, which gives the film its title Silence sounds good).

His images are the clearest example that photography is a universal language. They work for everyone, because everyone can read into them what they want: a playful joke, a reflection on society and human relationships, a moment in history. And still, after deciding what meaning to attribute to it, the doubt remains, it may be so or not. Each of Erwitt’s photos forces us to think, and conveys feelings like the tenderness of a mother looking at her daughter. It is a gymnastics for the mind, and for the heart.

The author of this article: Silvia De Felice

Da venti anni si occupa di produzione di contenuti televisivi per Rai in ambito culturale e ha ideato Art Night, programma di documentari d'arte di Rai 5. L'arte e la cultura in tutte le sue forme la appassionano, ma tra le pagine di Finestre sull'Arte può confessare il suo debole per la fotografia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.