The Canons Regular of St. Augustine probably did not imagine that the painting they commissioned from Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519) in 1481 would never be finished. Quite the contrary: they waited for years for the great Renaissance genius to return to Florence to complete his Adoration of the Magi, which the friars wanted to destine for the church of San Donato in Scopeto, then destroyed shortly before the siege of 1529. It took at least a decade for the canons to realize how inconstant Leonardo was: so, in the early 1590s, the commission was given to Filippino Lippi, who finished painting his own Adoration in 1496. That was the painting that later went on to decorate the church. Leonardo’s, on the other hand, was not only never placed on the altar that was to receive it, but was never even finished. Yet, despite its unfinished state, it can be counted among the seminal works of the Renaissance.

“It is an extraordinarily more modern work than anything that was being painted in Florence in those years.” Marco Ciatti, the Superintendent of theOpificio delle Pietre Dure, tells us this: together with Cecilia Frosinini, he directed the restoration of this immense masterpiece. The Superintendent is not very fond of the word “masterpiece,” but when confronted with such a work he decides to dissolve all reservations. It is a painting that introduced capital innovations for the art of the time. "The characters represent the most artistically significant part of the work: a turba of people who revolve around the main figures and who, with their different attitudes, their exchanges and their mutual relations, constitute the great novelty of Leonardo’s painting of that time. These motions of the soul of which Vasari spoke, this expression of feelings denote a spirit that anticipates the art of the sixteenth century. Let us think that in 1481 Neri di Bicci was fully active, just to make a comparison with what was around." Inspired by theAdoration that his friend Sandro Botticelli had painted about five years earlier and with which he had in fact invented the iconographic novelty of the Holy Family in a central position, Leonardo devised a work with a similar scheme, but he wanted to devote most of his attention to the reactions of the onlookers, amazed by the Child blessing them with his right hand, revealing his own divine nature: a gesture capable of arousing a jumble of convulsive emotions, entirely absent in Botticelli’s compassionate painting.

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Adoration of the Magi (1481-1482; charcoal drawing, ink watercolor and oil on panel, 246 x 243 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery |

|

| The Adoration of theMagi before restoration |

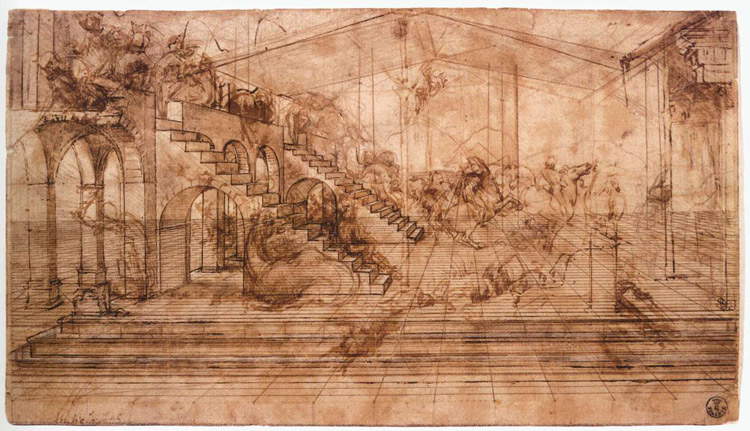

There is also more. The elaboration of the composition was quite laborious: the preparatory drawings that have been preserved testify to this. Notice how the artist organized the space: there is a kind of circular void around the figures of the Madonna and Child. Behind, the onlookers are arranged in a semicircle: they are leaning out, pointing, clearly expressing their feelings. Further back, a battle seems to be raging, on the right, while on the left we notice the portions of a building, apparently in ruins, actually under construction (or rather: under reconstruction, restoration), near which another small crowd is stirring. It is precisely the background, for Antonio Natali, that constitutes the main element for understanding the iconological substratum of Leonardo’s work. The building, in particular, the only detail present in both studies referring to the entire composition that are known (including the one preserved in the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe of the Uffizi, where the main figures do not appear), is in all probability the most important symbol of the work. “I believe that Leonardo,” Marco Ciatti continues, “wanted to convey a message to us in accordance with the writings of St. Augustine: humanity, following the coming of Christ, has changed, as is clear from the reactions of the characters, and Christ, with his birth, brought a new message.” The new evidence that has emerged from the restoration has in fact made it possible to definitively discard the old hypothesis that wanted the building in the background to be a ruined pagan temple and thus a symbol of ancient religions in decline following the advent of Christianity. Natali explains this well in his essay in the exhibition catalog Il cosmo magico di Leonardo. The Restored Adoration of the Magi, the exhibition that presented the masterpiece to the world after the lengthy intervention at the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, which began in 2012 and ended in 2017. The two flights of stairs of the building at the bottom closely resemble those leading to the presbytery of the basilica of San Miniato al Monte in Florence: Leonardo wanted it to be clear that the building we observe is a temple. A temple whose presence clashes with that of the battle scene on the right.

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Adoration of the Magi (1481-1482; charcoal drawing, ink watercolor and oil on panel, 24.6 x 24.3 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Study for theAdoration of the Magi (1481; pen and brown ink drawing on paper, 28.4 x 21.3 cm; Paris, Louvre, Cabinet des Dessins) |

The interpretation becomes clearer if one reads the book of the prophet Isaiah (whose presence is said to be so strong that it prompted Leonardo to depict the prophet, at least according to Natali, as the man standing on the left, absorbed in his thoughts), where the prophecy of Christ’s birth alternates with tales of devastation, such as the image of the ruined city symbolizing the hardening of the hearts of the people insensitive to Isaiah’s message, and tales of perpetual peace, founded, moreover, precisely on the rebuilding of God’s temple (“At the end of days, the mountain of the temple of the Lord will be erected on the top of the mountains and will be higher than the hills; to it shall flow all the nations”). This rebuilding, in accordance with the thinking of St. Augustine and in line with the writings of Isaiah (both held that salvation concerned all nations, not just Christians), will also be enacted by those whom the prophet calls “strangers” (“Strangers shall rebuild your walls, their kings shall be at your service, for in my wrath I have smitten you, but in my kindness I have had mercy on you”). It follows that the scene on the right evokes the destruction and wars that convulse the world, while the temple symbolizes the peace and reconciliation brought, at least according to the Christian interpretation, by the Lord. Sealing the universality of this message should have been contributed by a kind of roof joining the two sides of the painting, which was present in the Uffizi drawing but not included later in the altarpiece.

As mentioned, it is also thanks to the restoration that these hypotheses have been able to find comfort. The figure of the man standing on the stairs intent on masonry work could only be rediscovered thanks to preliminary investigations: it was identified through reflectographs, then the restorers brought it to light. “Our methodology,” Marco Ciatti explains, "always involves, for any work, a first phase of investigation and study, which serves for the exact understanding of the material, the artistic techniques, the problems of conservation of the material itself. We usually also do, at the same time, an in-depth study of the meanings, contents, what are called intangible values that a work conveys, because from the results of these two strands of study and research we understand what the objectives of the intervention project should be. So to fine-tune an intervention requires a study and research phase. In the case of a very difficult painting such as the Adorationof the Magi, as an unfinished work, all this took more than a year of work before we could decide that it was appropriate and possible to carry out a cleaning, and so our methodology made it possible to understand the feasibility of this intervention and to define, at least in a first phase of the executive project, the individual aspects." And to think that by many the restoration had been considered out of place: controversy had ensued because it was thought that an intervention could involve risks and cause damage to a work that several considered untouchable. Fortunately, this was not the case, and the Opificio was able to proceed with the restoration of what, at nearly two and a half meters wide by height, is the largest panel in all of Vinci’s production.

|

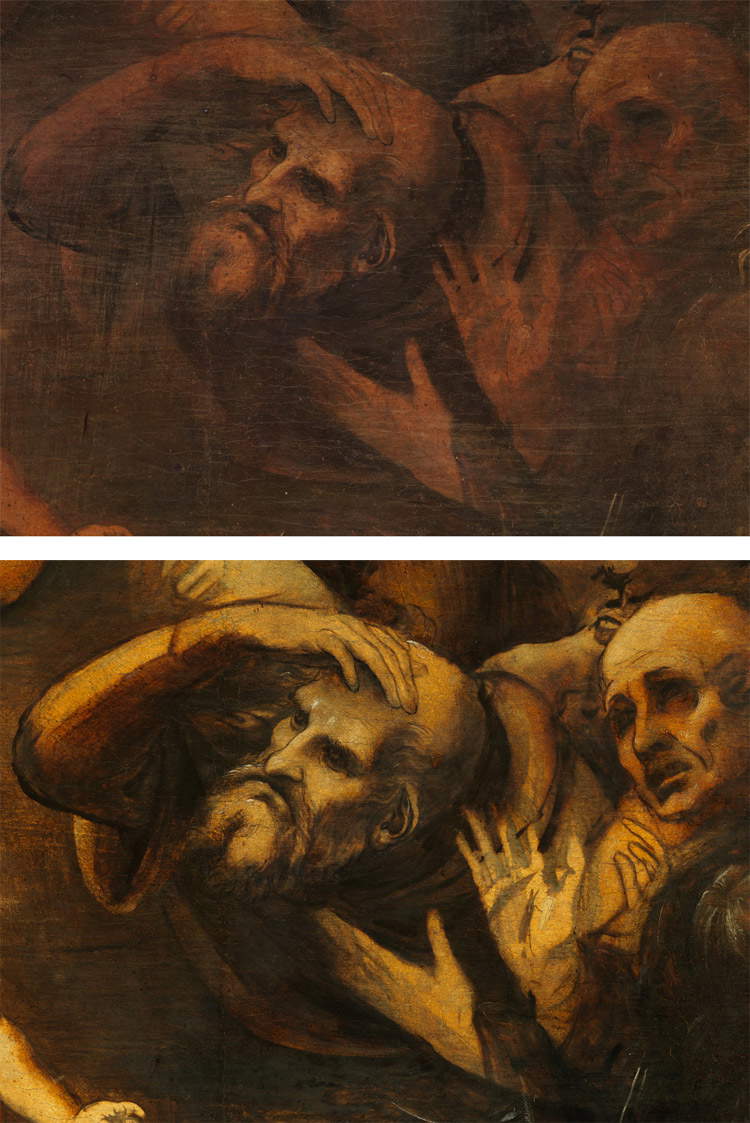

| Detail: the man on the temple before and after restoration |

|

| Detail: the supposed figure of Isaiah before and after restoration |

A restoration that involved both the surface and the structure (with intervention by Roberto Bellucci and Patrizia Riitano for the former, and Ciro Castelli and Andrea Santacesaria for the latter), and which had been necessary for several reasons. Meanwhile, the surface of the painting was in a decidedly precarious condition of legibility, caused by accumulations of materials that had been superimposed over the centuries. “These accumulations,” the Superintendent explained, “are quite frequent in grand ducal collections.” The painting, which remained in Florence after Leonardo’s departure for Milan, according to Vasari ended up in the home of a client of the painter from Vinci, Amerigo de’ Benci, one of the most important men in the Medici bank and the father of Ginevra, whom Leonardo immortalized in a very famous portrait. The earliest document attesting to its location, however, dates back to 1621: it is the inventory of Don Antonio de’ Medici ’s property that records the painting at the Casino di San Marco, but it is still to be expected that the work had been part of the Medici collections for some time. Then, in 1794 it entered the Uffizi Gallery: from there it would never move again. “In the works that come from the Medici collection,” Marco Ciatti continues, “it is very rare to find excessive cleaning effects, because there was a great respect for the material: however, in order to enliven the works and to meet the various aesthetic problems, all the maintenance interventions, which also followed one another with a certain frequency (by painters and restorers), were conducted through brush work, that is, with the addition and application of new layers of varnish to give more brilliance to the colors, and also layers of glue given with the idea of fortifying the solidity of the painting, and this resulted in the presence of this extremely heavy mass of materials.” But not only excessive cleaning: also tampering to achieve certain effects. At the top, for example, where Leonardo painted the sky: restoration has unearthed traces of blue application, which in the past someone hid with a covering patina so as to give theAdoration of the Magi the appearance of a large chiaroscuro monochrome. “The removal of this pigmented patina has reopened all the depth of the landscape, that aerial perspective that is typical of Leonardo, this silhouetting of the horizon that was not seen at all before.” A discovery that, moreover, belies those who believed that nothing interesting could be found beyond what could already be discerned by looking at the work.

|

| Detail: faces of bystanders before and after restoration |

|

| Detail: the Madonna before and after restoration |

But there is also an additional reason that led scholars to proceed with the restoration work. TheAdoration of the Magi, in fact, also had serious structural problems: the planks of the panel were worryingly separating. The breakage could have caused color to fall off, an eventuality that has moreover already occurred in the past, as could be deduced from some ancient plastering found during the work and made to repair some minor damage. Damage fortunately very limited, and this also thanks to the great quality of the pictorial layer, optimally prepared. A quality that, on the other hand, does not concern the support. “It is built with ten planks of poplar wood,” the Superintendent continues. “But these are boards of not good quality, as a choice and as a cut with respect to the trunk, so with a strong tendency to deform with aging. One of the fundamental points of all panel paintings is the relationship between the planking and the back crossbeams that control movement. In our case, there are two very massive, very rigid center crossbeams, and so when the planking tried to bend and deform, it could not build a continuous line of deformation, however, the internal force eventually discharged into the joints between the boards, and in four places the boards were completely separated...they had really opened up from top to bottom. These were through separations: it means that from behind it went all the way under the color in these gaps that had opened between the boards, that is, the color was basically bridging two boards that had opened, separated, which is very dangerous. All it took was a few movements out of plane to cause a break in the paint at the front, with possible falls.” And that is exactly what happened in ancient times, resulting in the small falls mentioned earlier. “Clearly we could not leave the work in this condition: we try to work with the future in mind, and so the work, after being in the restoration laboratory, could not have an inherent risk of this kind. It was, in short, a problem to be faced and solved: it was not easy, but we have a methodology proven by many years of study, research and experience, and we think we have solved this problem as well.”

The challenge, it can be said, has been met, and today we can admire theAdoration of the Magi roughly as Leonardo da Vinci’s contemporaries must have admired it. A challenge that, as we have seen, has solved several problems and allowed us to enter more deeply into the mind of the genius: we have the possibility of better deciphering some symbols, we have obtained evidence of the fact that, a unique case in his production, Leonardo had attended to the drawing directly on the panel, we can understand in depth theperspective organization of space, we can appreciate even more the imagination that led the artist to make so manifest the motions of the soul of his characters. A masterpiece, in short, returned to the public, who after the restoration will be able to read it more clearly and will be able to feel in a decidedly stronger way the fascination exercised by one of the greatest artists of all time.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.