At the Exhibition Center of the Albissola Museo Diffuso, the visitor is allowed to admire, displayed in a vitrine, a glazed ceramic depicting a sort of monster with deep-set eyes and a wide-open mouth, which almost seems to stare at the observer. The observer, in return, feels as if a sense of unease at being stung by this weird little creature, which amuses but also conveys a thread of unease. It is one of the many sculptures that Asger Jorn (Vejrum, 1914 Aarhus, 1973), one of the greatest artists of the 20th century, left in the Ligurian village where he spent much of his wandering existence. MuDA’s little monster was conceived for the house in which Jorn resided in Albissola Marina, and it had apotropaic functions, like many sculptures, ceramics and paintings that still adorn the mansion’s exterior walls.

|

| Asger Jorn, Untitled (1972; glazed earthenware, 44 x 27 x 20 cm; Albissola Marina, Museo Diffuso di Albissola, Exhibition Center). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

Admittedly, this is not a work that elicits feelings of ecstatic contemplation. But beauty, as commonly understood, was to some extent alien to Asger Jorn’s art. In 1955, a year after his arrival in Albissola Marina, and thus at a time when he had already become quite familiar with the art of ceramics, the Danish artist exhibited his most recent works in his native Copenhagen at the Kunstindustrimuseet. In the catalog for that exhibition, Jorn wrote: “If the normal, the traditional and the masterful equate to the beautiful, then the rare, the remarkable and the singular must equate to the ugly. Long live ugliness, which creates beauty. Without ugliness there is no beauty, only obviousness, indifference, boredom. The non-aesthetic is not the ugly, but it is the boring.” Ugliness became, as a result, an important stylistic feature of his achievements. Ugliness, for Jorn, was a kind of reaction. Against academic, immobile and stuffed art. Against rationalism and functionalism, guilty of caging creativity and subjecting drives and feelings to the rigid control of reason, to the point of deserving, according to Jorn, the definition of “non-aesthetic art.” And also against the individualism ofabstract expressionism. The ugly, in such a context, becomes an aesthetic necessity.

To similar conclusions would come, a year later, a particularly visionary painter like Giuseppe “Pinot” Gallizio (Alba, 1902 - 1964), who in 1957 would later found, together with Asger Jorn and others, theSituationist International. Wrote Gallizio: We have created a new aesthetic theory, superior to existing ones, through the consideration that the non-aesthetic is not the Ugly and the Repugnant, but the Insignificant and the Boring. Ugliness as a synonym for spontaneity, creativity and singularity (also understood as the direct expression of the individual, which is always manifested in the context of acollective experience) constitutes the foundational basis of Jorn’s artistic credo. “Our goal,” the artist wrote in 1949 in his Speech to the Penguins, one of the founding texts of the CoBrA group, of which he was one of the founders, “is to free ourselves from the control of reason, which has been and still is what the bourgeoisie has idealized in order to seize control of lives.” In such a context,irony, a tool that pertains much more to the logic of the ugly than the beautiful, becomes an indispensable aesthetic foundation. For Jorn, no form can be capable of making itself the bearer of a single content: irony therefore becomes a means of probing meaning (but not of arriving at truth, since truth is not unique and especially not stable), of stimulating a response from the audience, of enacting the social critique that is a constant that permeates virtually all of his art. A work such as The Mayor’s Portrait, also known ironically as The King, gives a dimension of this aspect of Jornian research: a funny and awkward individual who takes on the appearance of a kind of elongated mask sits firmly anchored to his own chair, with which he ends up merging. It is an amused, but at the same time strong, reading of the institutional office, the man, and his position. It is, moreover, one of Asger Jorn’s first ceramic creations during his time in Italy.

|

| Asger Jorn, Portrait of the Mayor or The King (1954; glazed earthenware, 40 x 22 x 19 cm; Albissola Marina, Museo Diffuso di Albissola, Exhibition Center). Ph. Credit MuDA Albissola |

It should be noted that experimentation with ceramics played an important role in the art of Jorn, who discovered it in Denmark but delved into it systematically during his Albissola years. Meanwhile, ceramics, a traditional art, constituted for Jorn an important synthesis of popular artistic expression: always interested in spontaneous artistic manifestations far removed from the Academy, the Danish artist also ended up amassing a sizeable collection of ceramics and objects made by local artisans, on which, moreover, Jorn often intervened in accordance with the poetics of détournement (the subversion, often ironic and humorous, of the meaning or aesthetic canons of a work or writing), that “flexible language of anti-ideology,” as Guy Debord called it, that characterized the artistic practice of the Situationists. Particularly significant in this regard is a 1959 painting, known as Le canard inquiétant (“The Disturbing Duck”), which Jorn exhibited that year, along with other détournés paintings (there were twenty in all), in an exhibition at the Galerie Rive Gauche in Paris that bore the title Modifications.

For that exhibition, Jorn had purchased twenty low-quality paintings, and on each of them he had affixed his own modifications, which involved subverting the meaning of the original work. There were many levels of interpretation of this practice: two of them were suggested by Jorn himself, who presented two texts in the exhibition catalog, one aimed at the “general public,” and the other aimed at “connoisseurs.” The general public was provocatively urged to see, in the modified work, a new life for the work itself, which became a symbol of cultural renewal. The Danish artist wrote in verse, “porquoi rejeter l’ancien / si on peut le moderniser / avec quelques traits de pinceau? / �?a jette de l’actualité / sur votre vieille culture. / Soyez à la page, / et distingués / du même coup. / La peinture, c’est fini. / Autant donner le coup de grâce. / Détournez. / Vive la peinture” ("Why throw away past things / if it is possible to modernize them / with a few strokes of the brush? / This makes current / your old culture. / Be fashionable / and distinguish yourselves / at the same time. / Painting is finished. / Give it the coup de grâce. / Apply détournement. / Long live painting.“). As for the ”connoisseurs," on the other hand, the invitation to them was to get out of the logic of the work of art as an end, and to enter instead into that of the work of art as a means capable of creating a bond between the subject who creates the work (and, Jorn argued, when the latter does so for its own pure pleasure, the attitude becomes irreconcilable with interest in the object), and the one who receives it. And it is on this link that détournement acts: “dévaloriser,” “de-valorizing,” to create new values.

But there is also more. Karen Kurczynski, in her monograph on Asger Jorn, has devoted a profound analysis to Modifications. This series, meanwhile, stands as a critique of institutions: far from expiring into a simple and banal iconoclasm, the détournés paintings placed attention on anonymous works yet belonging to a traditional creativity that the Academy had marginalized but that for Jorn was more than worthy of attention. Again, the Modifications, as indeed Jorn himself implied in his two writings “to the general public” and “to the connoisseurs,” aimed to make the viewer a participatory subject, insofar as the détourné painting provokes in him a reaction of empathy or hostility, in accordance with the concept of “art” according to Jorn (“Kunst er agitation,” or “Art is agitation,” he had written in 1948). Again: go back to Le canard inquiétant. Jorn modifies an unremarkable painting, a tranquil country landscape with a pond in which some swans swim, by having a huge, deformed duck emerge from its waters, constructed with thick, rapid, rough brushstrokes, and then modified with touches of color that make it an even more bizarre and alienating being. For Kurczynski, there is also an attack on the cliché that wants to tie painting totechnical skill: Jorn’s duck remains in a state of perpetual unfinishedness, because for the artist, full wholeness involves a separation from real experience. And again: according to the U.S. scholar, the ironic dialogue between the relaxing pre-existing painting and the ugly duck (i.e., between two elements aesthetically at opposites) is meant to suggest to the viewer the vastness of forms of expression in a complex society.

|

| Asger Jorn, Le canard inquiétant (1959; oil on recovered canvas, 53 x 64.5 cm; Silkeborg, Museum Jorn) |

Returning to Asger Jorn’s relationship with ceramics, it can be added that, at the time of the Danish artist’s arrival in Italy, ceramic art was experiencing a particularly fortunate season, since a large number of artists (beginning with Lucio Fontana and Leoncillo) had begun to explore its possibilities, to consider it a field on which it was possible to conduct experimentation that moved in a different direction from that of sculpture as it had been practiced up to that time. Indeed, it is possible to say that, in a certain way, the interest in ceramics had arisen thanks to Lucio Fontana, who in 1936 went to Albissola, to his friend Tullio Mazzotti (whom Marinetti had nicknamed Tullio d’Albisola), a Futurist ceramist and owner of one of the historic factories in Albissola Marina, and began to reflect on an art form that guaranteed great freedom and that in some ways annulled the distance between avant-garde art and kitsch art, in a dialectical relationship that was long researched by Jorn himself. Fontana was, moreover, one of the first contacts Jorn had at the time of his arrival in Italy, and it is to be expected that some of the Danish artist’s work on ceramics would take its cue from Fontana’s experiments. The two were also the promoters of one of the highest events in the history of twentieth-century Italian art, theIncontro Internazionale della Ceramica, which took place in Albissola in the summer of 1954 and was attended by many of the great artists of the time: in addition to Fontana and Jorn, Karel Appel, Corneille, Enrico Baj, Roberto Sebastian Matta, Tullio d’Albisola, Sergio Dangelo, Emilio Scanavino, �?douard Jaguer, and Yves Dendal took part.

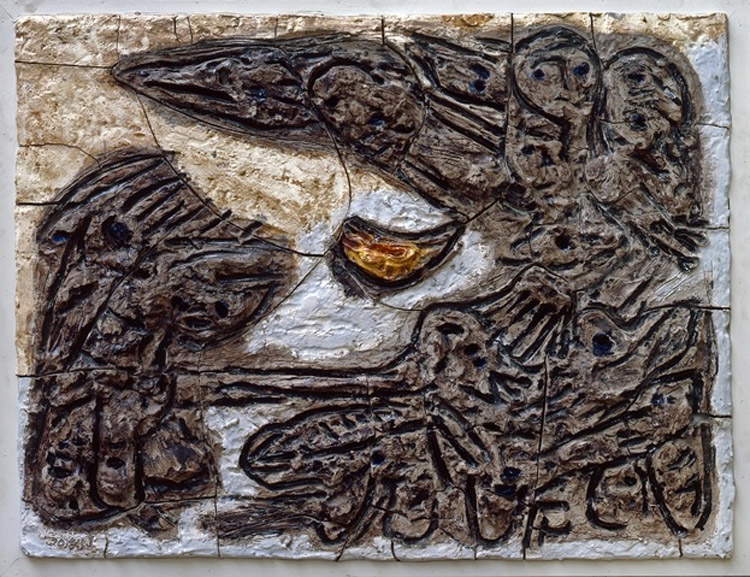

Ceramics, for Jorn, had a certain predisposition not to embody well-defined concepts, but rather to leave the viewer with broad faculties of interpretation. A work such as Tidlig vår (“Beginning of Spring”) is as illustrative as ever: Jorn suggests a title, but it is up to the observer to probe these figures, which, in his production, are never entirely abstract (in this case, Hans Kolstad wants to see in the composition a female bird spreading her wings to protect her young). Relief ceramics were much practiced by Jorn at this stage: “these reliefs,” writes Ursula Lehmann-Brockhaus, “show that the artist did not simply transpose pictorial conceptions from canvas to clay, rather that he immersed himself in the material and technique in order to make the most of the expressive and figurative possibilities contained therein. He molded largilla with expressive gestures and let limmagine form plastically and, through the glazes, live as a chromatic work. He also knew how to include a linear component, a rhythm of lines, taking advantage of the need to dismember the firing slab into irregular pieces rather than a linear grid. In this triad composed of volume, color and line, a union possible only in ceramics, Jorn found a mode of expression very much suited to his artistic temperament.” Jorn never abandoned ceramics: at the Exhibition Center of the Albissola Diffuse Museum it is possible to observe, for example, a series of plates that belong to the extreme stages of his career. And even in these plates, Jorn did not stop experimenting: he tried his hand at complementary colors, at the potential of form, at the particular dripping that responds in an ironic and humorous way to that of Jackson Pollock (who, moreover, is preceded by Jorn: the Danish artist’s first experiments with the dripping technique date back to 1938).

|

| Asger Jorn, Tidlig vår (1954; glazed earthenware, 103.5 x 135 cm; Silkeborg, Museum Jorn) |

|

| Asger Jorn, Untitled (1971; glazed earthenware, 52 cm diameter; Albissola Marina, Museo Diffuso di Albissola, Exhibition Center). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Asger Jorn, Untitled (1972; glazed terracotta, 51 cm diameter; Albissola Marina, Museo Diffuso di Albissola, Centro Esposizioni). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

Finally, it is interesting to note that that reappraisal of ugliness mentioned in the opening paragraph was also propelled by the International Ceramics Meeting: the works exhibited in 1955 in Copenhagen were all created on that occasion, and it is there that the discourse on “ugliness” takes shape in a timely and systematic way. But Asger Jorn also proposed something else: “the Albissola meeting was not a coincidence, but a new step toward the construction of a new artistic principle, that is, a free artistic methodology that has the name Mouvement Internationale pour un Bauhaus Imaginiste, turned against architectural rationalism and against empiricism.” Thus was born the movement of free artists that would form the basis of theSituationist International.

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.