A recurring theme in art is the desire a man feels when he stands before a woman. In this article, Pilar Turu in Cultura Colectiva analyzed the theme, narrowing it down to 19th-century art. Here is the link to the original, while below you can read the article in my translation. Happy reading!

Man’s desire for woman is a recurring theme in art. Various styles or representations in different eras allude to the feeling that woman generates in man. Art reflects the mentality of both a particular era and the present. And from the nineteenth century onward, from neoclassicism to symbolism, one can see in art a search for representations that show the male gaze in front of a woman; the way they pose toward them and observe, desire, fear or even spy on them.

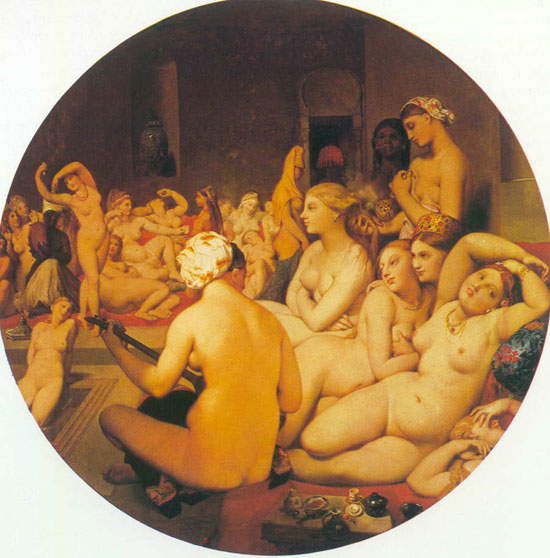

A work of great importance to art history in both quality and theme (made during this period) is The Turkish Bath by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867). The artist won the first Prix de Rome (ndt: a scholarship with which the winner could study in Italy) in 1801. His work is characterized by great finish and a vaguely Baroque style. A physical flaw appears in the making of his characters: they have heads that are disproportionate to the rest of their bodies. Thanks to Orientalism, his compositions become romantic. Orientalism is a complex phenomenon of representations of the East in the West. Through an interdisciplinary study, based on literary, historical, anthropological, and political sources (all European), we come to observe that Orientalism was produced by both academic and historical and power institutions, which created an erroneous and generalized notion of the Orient (From Araceli Tinajero, Orientalismo en el modernismo Hispaoamericano. Purdue University, 2004)

|

| Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, The Turkish Bath. |

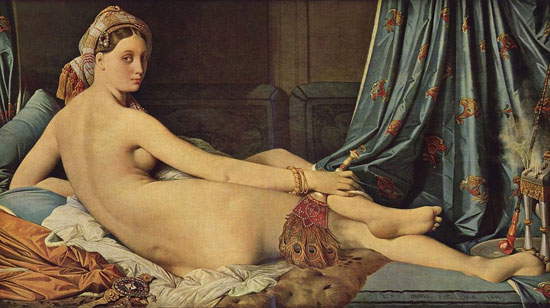

This means that Orientalism makes the Orient a European invention based on exoticism, the novel, legends and myths. It is a fusion of what the European knows about the Orient and what Western man interprets or adds to this knowledge. Many of the works that were produced in Europe during the nineteenth century describe themselves in these terms. They are images in most cases devised, reinvented, and seeming to bear witness to what the Near East or Mediterranean Africa would be. Although Ingres never traveled to the Orient, we see how he added to his work the exotic motifs in vogue, such as the turban worn on the head of the Great Odalisque. The Turkish bath, on the other hand, represents male imagery. The circular composition of the work refers to what would be an image seen through a peephole. The viewer can see the girls, while they move as they please unaware that they are being spied on. It is voyeuristic conduct; I can see them, however, not touch them, and they are naked. Since sexuality was a censored topic at the time, the female nude fascinated men even more.

|

| Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Great Odalisque |

Another painting that shows us the imagery of Victorian society is The Awakening of Conscience by William Holman Hunt (1827-1910). It is an everyday scene of the time depicting the reality of gentlemen who, due to the fact that their wives were often ill and always very chaste, enjoyed the company of prostitutes.

|

| Vasily Polenov, Sick Woman |

In the case of The Awakening of Conscience, since we are in the context of the Victorian era, we recognize that a classy woman is not depicted, nor is she a chaste bride, for she is neither sick nor pale; she is not lying as noble women were wont to present themselves, but she is a prostitute by her long, loose, red hair and posture.

|

| William Holman Hunt, The Awakening of Consciousness. |

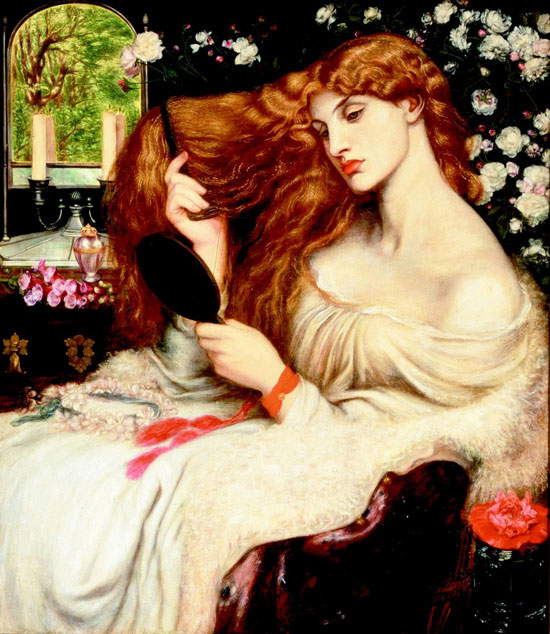

On the other hand, a Symbolist work that recreates male imagery and desire is Lady Lilith (1868) by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). Lilith, a legendary figure, was the first bride of Adam, even before Eve. According to Jewish belief, she left Eden by her own will, moved near the Red Sea and became the mistress of Samael and other demons. She is the representation of evil. As femme fatale, man will try to possess her, but not to love her. Lilith represents the feminine ideal of man. She is a synaesthetic representation, as she alludes to the senses. The presence of flowers and nature hints at the sense of smell. The use of different fabrics or the color of hair to touch and sight. Everything invites one to feel the work, to love it. Here, Dante represents his lover. Lilith’s long red hair reveals her to be a prostitute.

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Lady Lilith |

In Ophelia (1852) by John Everett Millais (1829-1896), we see the ideal of the Victorian woman. Unlike Lilith, the ideal of woman that men of the time truly seek is one who died for the love of a man. Death is undoubtedly eroticized and seen as beautiful, close. She is not feared but desired.

|

| John Everett Millais, Ophelia |

Slightly more sexualized, but representing the same ideal as the previous one, is Flaming June by Frederic Leighton (1830-1896). In this work the woman sleeps peacefully in a comfortable position, thanks to which we see her corporeity and perfect anatomy. It is not a sickly body, it is not a pale body. She invites us to touch her, and there is no doubt that her fragility prevents us from possessing her. A blazing sun appears in the background, a warm sun that lets us know that the body, to the eye, enjoys good health. With English aestheticism, sensuality, eroticism is alluded to; woman becomes an object of desire. The merit of English aestheticism lies in redeeming the eroticism and sensuality of the time and applying them to beautiful forms. The women who are sleeping represent the male imagination: a woman who sleeps when the man is away and wakes up with his kiss when he returns.

|

| Frederick Leighton, Blazing June |

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.