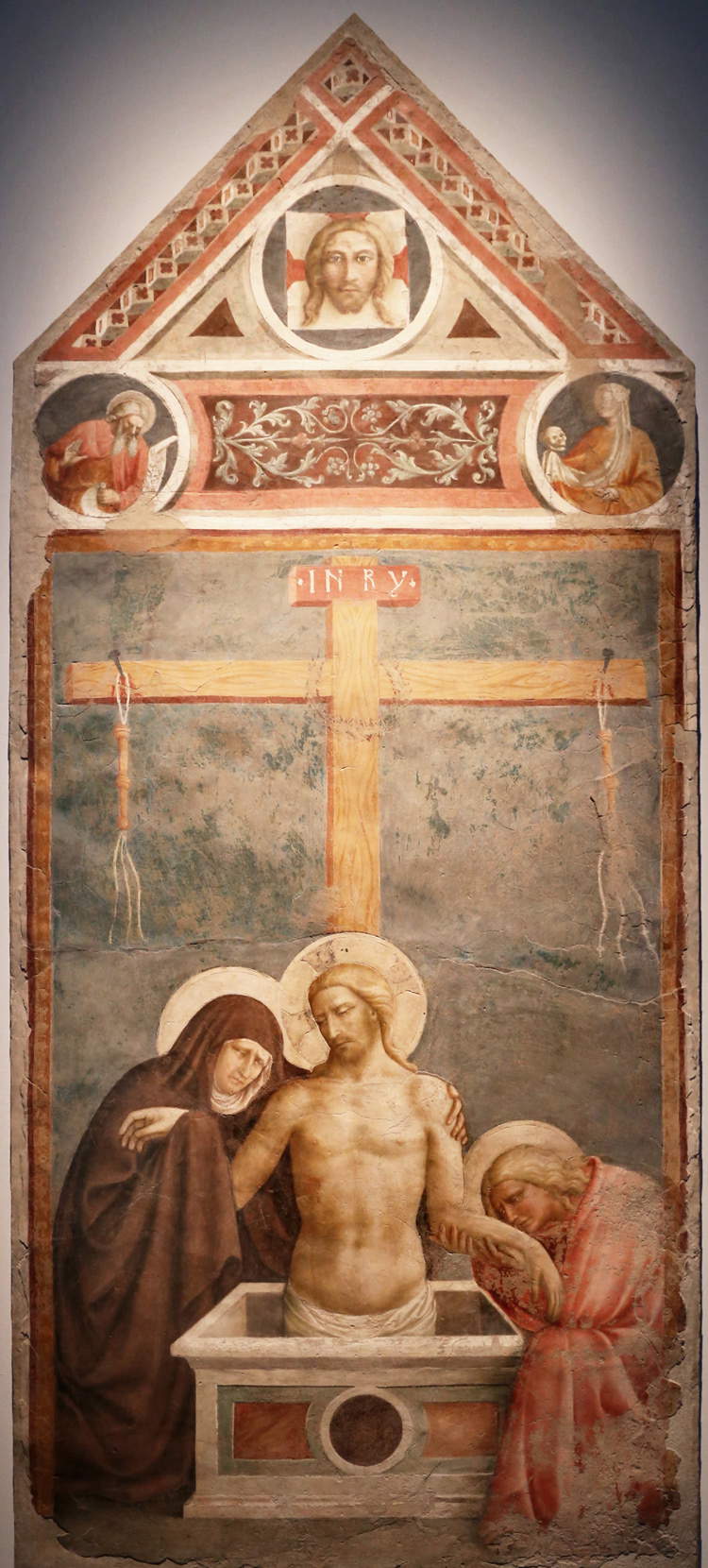

“Neo-Giottesque locutions”: with this expression, the great art historian Roberto Longhi referred to the figures that appear in the very famous Christ in Pieta by Masolino da Panicale (real name Tommaso di Cristoforo Fini, Panicale, 1383 - Florence, c. 1440), perhaps the most famous masterpiece of the Tuscan artist, and certainly, as scholar Anna Bisceglia has written, “one of the most significant testimonies of the painter’s activity.” A masterpiece that remained hidden for who knows how long from the eyes of those who went to the baptistery of the Collegiate Church of Sant’Andrea in Empoli, the place for which it was conceived: at an unspecified time, in fact, it was covered with a layer of plaster, and only in the late 19th century, when the dullness was removed, did the marvelous Christ in Pity re-emerge from oblivion, immediately arousing the attention of the greatest critics, given its exceptional quality. That work happened so, out of the blue, and consequently nothing was known about her: but one could clearly guess that she was the work of a great artist. And the first to formulate the name of Masolino was Bernard Berenson, who advanced the name of the Tuscan painter in 1902: the American art historian was at that time thirty-seven years old, and for two had been married to Mary Whitall Smith in the chapel of the Villa I Tatti in Florence. For some time already he had become a frequent visitor to the Collegiate Church of Empoli, a treasure chest of art treasures that had attracted his keen attention.

The attribution to Masolino of the Christ in Pieta was formulated in 1902 in an article published in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, still today an indispensable point of reference for studying the artist and his work, given the convincing solidity and profound methodological rigor of the arguments Berenson had put forward in support of his hypothesis. “In the baptistery of Empoli,” Berenson had written, “we admire a Pietà in which the intensity of emotion and noble sobriety recall the finest compositions of Bellini.” As soon as it was rediscovered, Christ in Pity had been attributed to Masaccio (real name Tommaso di ser Giovanni di Mone Cassai, Castel San Giovanni, 1401 Rome, 1428): such was, for example, the position of Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, who in 1883, the first to speak of the work, believed it to be a joint product of Masaccio and Masolino. But for Berenson there was little doubt: it was a work by Masolino. It could not have been Masaccio’s, because the latter, “as much in the panels as in the frescoes, always used darker, more opaque colors.” Here, in the Christ in Pieta, on the contrary “we find the blond hues and transparency that characterize Masolino’s frescoes.” And again, typical of Masolino are the aquiline profiles, or connotations of the Virgin, reminiscent of those in his Madonna of Humility preserved in Munich, or even those of the turbaned man who appears in the fresco of the Resurrection of Tabita that Masolino painted in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence. Or, a Christ that “Masaccio could never have painted of such an unsound form and stature,” especially since Christ’s face resembles that of the Jesus who appears in the Baptism of Christ in Castiglione Olona, or even in the Preaching of the Baptist, another fresco that Masolino painted in the Baptistery of the village near Varese. Finally, Berenson drew attention to the figure that appears at the top of the fresco: the “prophet who raises his arm to heaven in the presence of the horrible spectacle he glimpses.” In all Masaccio’s art there is, Berenson suggested, “no type so purely inspired by fourteenth-century taste.” And, moreover, that character manifested a remarkable resemblance to theEternal we see in the Munich Madonna. So, no features in common with Masaccio, many similarities with other works by Masolino.

In 1905 Berenson’s insights were happily confirmed, albeit indirectly, by the discovery of a document in which, without a shadow of a doubt, it could be read that Masolino had been active in Empoli. The credit for the discovery belongs to the scholar Giovanni Poggi, who found a note, dated November 2, 1424, in which seventy-four gold florins were paid to “Maso di Cristofano,” identified as a “dipintore da Firenze,” for the execution of the paintings that decorated the chapel of the Compagnia della Croce, which was located in the church of Santo Stefano, not far from the Collegiate Church of Sant’Andrea. In the document, we read that “said chapel above named chella Compagnia had it painted for infino addì 2 novembre MCCCCXXIIII pagano al Maso di Cristofano dipintore da Firenze fiorini settantaquattro doro come apparisce in su gli antichi nostri libbri”: so there is no documentary evidence for the Christ in Pietà, but it is nonetheless important and decisive to know that, in 1424, Masolino was in town. The frescoes mentioned in the document would be rediscovered in 1943, and in those same years the Christ in Pieta was being detached for conservation reasons: it was 1946 when restorer Amedeo Benini proceeded with the detachment of the fresco, bringing it back on top of a wooden frame. Today, Masolino’s masterpiece is on display at the Museo della Collegiata di Empoli, in the very building (currently attached to the museum) that formerly housed the small church of San Giovanni Evangelista, which later became the baptistery of the Empolese Collegiate Church: it can therefore be said that Christ in Pieta is still in the place for which it was intended.

|

| Masolino da Panicale, Christ in P ity (1424; detached fresco, 280 x 118 cm; Empoli, Museo della Collegiata di Sant’Andrea). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| The room housing Masolino’s work at the Museo della Collegiata in Empoli. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Masolino da Panicale, Madonna of Humility (1423; tempera on panel, 96 x 52 cm; Bern, Kunsthalle) |

|

| Masolino, Madonna lactans (c. 1423; tempera on panel, 110.5 x 62 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| The man with the turban in the Resurrection of Tabita in the Brancacci Chapel |

|

| Masolino, Baptism of Christ (1434; fresco; Castiglione Olona, Baptistery) |

This fresco by the great Tuscan artist is striking for its moving intensity: Christ, in the center, is lifeless and rises from the tomb, in which he has just been laid. He is mourned by his mother and the apostle John, as per typical ancient iconography. Above, in a perfectly central position, rises the cross, from which hang some of the instruments of the martyrdom suffered by Jesus: two scourges, dangling from the nails and slightly moved by a breath of wind, and the crown of thorns, stuck in the vertical arm. In the cusp, at the three vertices of the triangle, we have two figures of prophets (in the vertices of the base), namely Isaiah and Ezekiel, who respectively foretold the birth and death of Jesus (it is precisely to death that the skull in Ezekiel’s hands refers), and the figure of the Holy Face, in the summit position.

It is a sober, essential composition, almost stripped down to its bare essentials: yet it is a fundamental work, because it testifies to Masolino’s rapprochement to the ways of the younger Masaccio, of which the Christ in Pietà can in some ways be considered a kind of reflection. Masaccio and Masolino, as is well known, had collaborated on several works: the Carnesecchi Triptych, the Saint Anna metterza, and the very famous cycle of frescoes in the aforementioned Brancacci Chapel. And confirming a 1424 dating of the Christ in Pieta also concurs with the fact that, looking at the works that Masolino created alone, the greatest tangencies between his and Masaccio’s art occur precisely in the years of their collaboration, that is, between 1424 and early 1426. “At the time of Masaccio alive and rampant,” Longhi wrote: everything in Masolino that moves away from Masaccio also certifies “a moving away from that time” (in the works Masolino produced after the end of their collaboration, there was in fact a progressive detachment from Masaccio’s achievements). And it was precisely thanks to Masaccio’s spur, Longhi argued, that Masolino approached a typically neo-Giottesque formal rigor, he who, in the earliest works we know (such as the Madonna of Humility preserved in Bern and certainly a work of 1423, or the Madonna lactans in the Uffizi, of uncertain date but which some art historians , among whom Miklós Boskovits stands out, have dated to the 1920s) manifests those sinuosities and calligraphisms typical of flamboyant Gothic, which disappear alto gether in the Christ in Pieta, only to return in the works of the 1430s, by which time Masaccio had already disappeared. “Neo-Gothic locutions,” then: the essentiality of the composition, its stern tone, the solid plasticism of the figures, without forgetting a particularly revealing detail, as Longhi himself suggested, namely the head of Christ, extraordinarily similar (even in the hairstyle!) to the one Masaccio would shortly thereafter paint in the Tribute in the Brancacci Chapel (although, to tell the truth, Longhi and other leading art historians have also assigned to Masolino’s hand the same head of Christ in the Tribute). Not to mention that the tomb, elegantly foreshortened in central perspective, and the strong chiaroscuro contrasts of the robes (but also of the body of Jesus: the modeling represents one of the pinnacles of Masolino’s modernity), as Rosanna Caterina Proto Pisani has written, constitute in this painting of the “signs of the profound renewal that took place in Florentine painting in the first two decades of the century.”

But Christ in Pity also denotes other interesting suggestions. Precisely that very fine modeling that we have the opportunity to observe in the body of Christ could be linked, according to some, to the knowledge of classical models, which Masolino could have deepened with a trip to Rome, which is also mentioned by Giorgio Vasari in his Lives: “et andatosene in Rome to study, while he stayed there, he made the room of the house Orsina Vecchia in Monte Giordano; then, for an evil that the air made him head, returned to Florence, made in the Carmine allato alla cappella del Crocifisso the figure of S. Peter which can still be seen there.” Regarding Masolino’s probable knowledge of classical texts, Stefano Borsi has written that “the Christ, somewhat Apollonian and inspired by ancient models, suggests that Ghiberti is still seen as an authority.” On the same subject, however, Umberto Baldini had already expressed himself in 1958, pointing out that “the new moral and physical entity of the Christ in Pieta can be explained only and entirely by an albeit plausible familiarity with Ghiberti’s sculpture”: Baldini, too, agreed in identifying Masaccio as Masolino’s true point of reference.

|

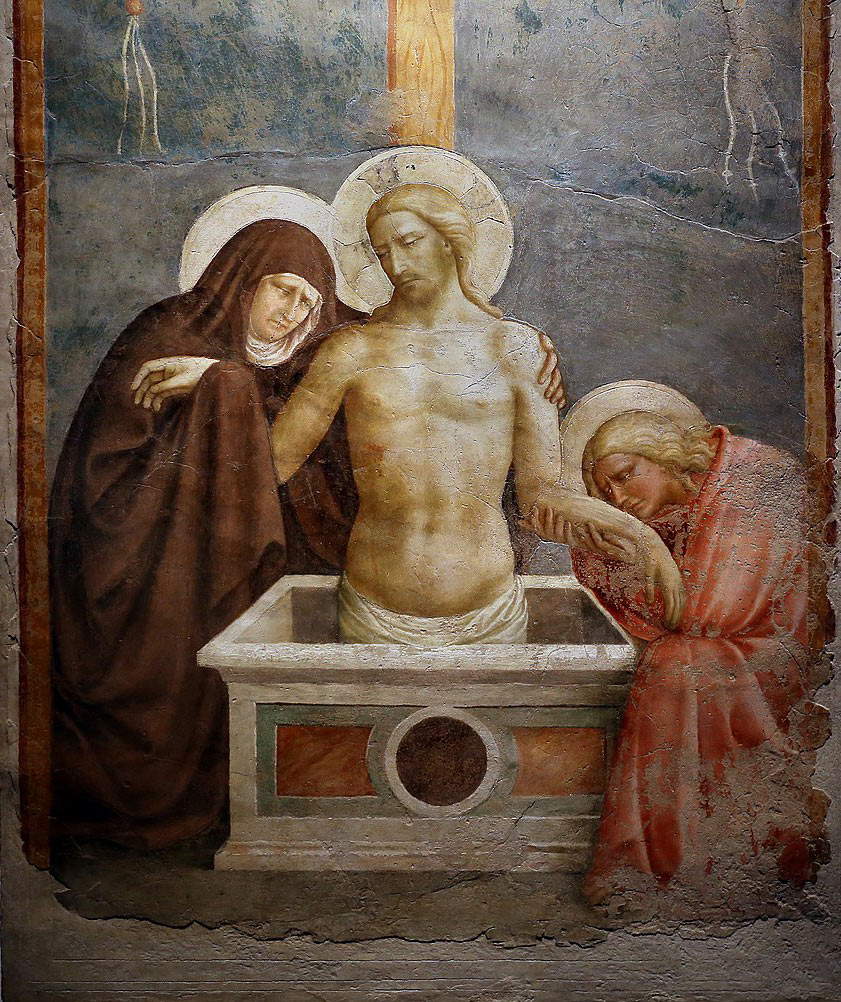

| The protagonists of Masolino’s Christ in Pietà. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Saint John the Evangelist. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| The Virgin and her son |

|

| The face of the Christ in Pieta by Masolino. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Masaccio (and Masolino?), Tribute (c. 1425; fresco, 255 x 598 cm; Florence, Santa Maria del Carmine, Brancacci Chapel) |

|

| The face of Christ in the Tribute |

Visitors passing through what was once the baptistery of Empoli, however, are struck above all by the great pathos that the Christ in Pity is able to unleash. A pathos that is not spectacular, but is experienced intimately by the protagonists, whose distraught faces are rendered by Masolino with skillful naturalism. And to their expressiveness is added, equally powerful, their gestures: observe the left hand of Our Lady, which pitifully encircles her son’s shoulder, or the right hand that holds his hand, and note also John the Evangelist, who bows on his knees, takes Jesus’ left arm in his hands, brings his lips close, touches it.

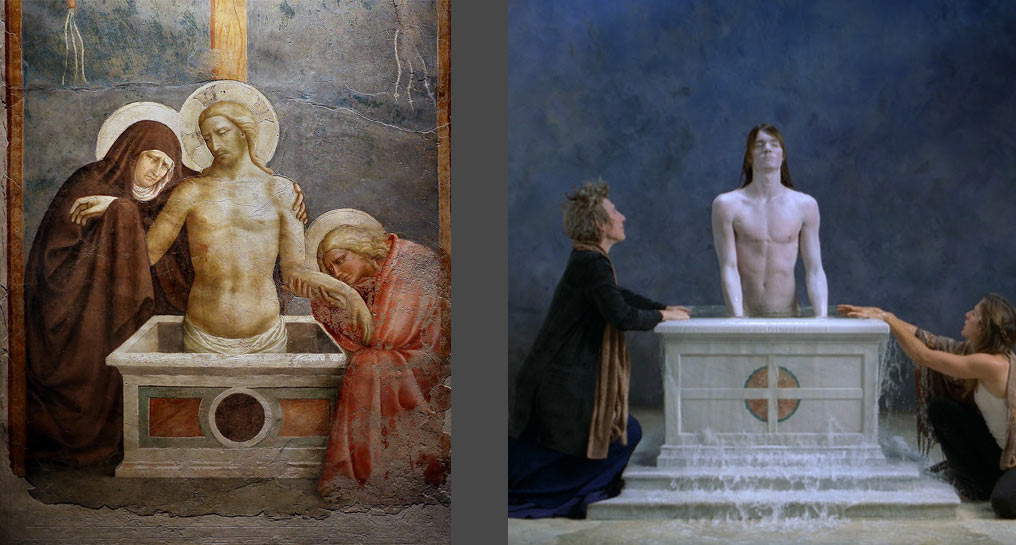

A pathos so intense that it did not leave indifferent one of the most celebrated contemporary artists, Bill Viola (New York, 1951), who was inspired by Masolino’s Christ in Pieta to create one of his best-known and most appreciated works, Emergence, from 2002. This is how the artist described his own masterpiece: “Two women sit on either side of a marble cistern in a small courtyard. They wait in patient silence, only occasionally acknowledging each other’s presence. Time becomes suspended and indeterminate, the purpose and destination of their actions unknown. Their vigil is suddenly interrupted by an omen. The younger woman turns abruptly and observes the cistern. She watches, in disbelief, as a young man’s head appears, and then his body rises, water spills from all sides, onto the base and the pavement of the courtyard. The falling water catches the attention of the older woman, and she turns to witness the miraculous event. She stands up, drawn by the young man’s presence. The younger woman takes his arm and caresses him, as if greeting a lost lover. When the young man’s pale body reaches its full extent, he staggers and falls. The older woman catches him in her arms, and with the help of the younger woman, struggles to gently lay him on the ground. He lies prone and lifeless, and is covered by a veil. Cradling his head between her knees, the older woman eventually shags in tears as the younger woman, overcome with emotion, tenderly embraces his body.”

The work, commissioned for a series known as The Passions (and from whose catalog the text just quoted is taken), is imbued with complex meanings to which the many symbols Bill Viola employs refer: from water, omnipresent in his video art masterpieces, to the passage of time (Viola’s videos “insert time into images,” Giorgio Agamben has written), from Masolino’s tomb, which in Bill Viola becomes a kind of well, to the young man’s body falling to the ground. The overall meaning of Emergence is difficult to summarize in a few lines: however, it is interesting to dwell briefly on its relationship with the great Tuscan painter’s Christ in Pity. Bill Viola is not interested in repurposing mere reinterpretations of ancient works: probably, he was inspired by Masolino’s work because he caught a kind of ambiguity in it. Christ has died, but he has not yet been buried. He has been deposed from the cross, which we see behind the protagonists, marking the perfect symmetry of the composition, but he stands upright on the edge of the tomb. Christ is suspended between life and death, and shortly thereafter he will rise again. Emotion and ambiguity: these are perhaps the two features of Masolino’s work that most fascinate Bill Viola. In Bill Viola, the two women holding the young man’s body allow themselves to weep mournfully, but intimately and composedly: this is the same thing that happens in Masolino’s work to the Virgin and St. John (of the latter in the video, at one point, the gesture of the hands is taken literally). And just as in Masolino the Christ is suspended between life and death, the same can be said of the young man emerging from the well in the American artist’s video: many have seen, in his emergence and subsequent fall, an allegory of life.

|

| Bill Viola, Emergence (2002; high-definition color video rear projection on a wall-mounted screen in a darkened room, 213 x 213 cm, duration 1140; performers: Weba Garretson, John Hay, Sarah Steben. Courtesy Bill Viola Studio) |

|

| Masolino and Bill Viola in comparison |

|

| Masolino and Bill Viola compared in Bill Viola’s 2017 monographic exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi. Courtesy Palazzo Strozzi |

A cornerstone of Masolino’s production as a watershed work in his artistic career (as well as one of his earliest known works, despite the fact that it was made by the artist when he was more than forty years old), a fundamental masterpiece of art history since it is one of the first paintings to turn toward the new Renaissance paths traced by Masaccio, a fresco made “technically perfectly,” as the restorer Giuseppe Rosi, who took care of it in the 1980s, wrote, Christ in Pity is certainly one of the most remarkable works of the entire fifteenth century and capable, as we have seen, of still dialoguing, strong and modern as it is, with contemporaneity. It is a work in which the intensity of feelings moves anyone who admires it, at the Museo della Collegiata in Empoli, to awe and reflection. And, as Berenson suggested, the Tuscan city can boast of having two supreme masterpieces by Masolino: one is the Madonna and Child in the church of Santo Stefano (“the most beautiful”), the other is the Christ in Pity (“the noblest”). With this very reflection Berenson concluded his 1902 essay: “Ainsi, Empoli peut se glorifier de posséder deux peintures de Masolino qui, si elles ne comptent pas parmi les plus importantes, sont, l’une la plus charmante, et l’autre la plus noble des compositions de cet artiste” (“therefore, Empoli can glory in possessing two paintings by Masolino which, if they really cannot be counted among the most important, are nevertheless one the most beautiful and the other the noblest of this artist’s compositions.”)

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.