From the decommissioned church of the Confraternity of the Most Holy Rosary in Polla, a town set in the beautiful setting of the Vallo di Diano, comes the canvas depicting Saint Gaetano of Thiene giving the rule, by Michele Ragolia (Palermo, 1638 - Naples, 1686). It was restored during the 1980s and placed at the Church of Christ the King in Polla; its good state of preservation and artistic merits have attracted the attention of several scholars.

In the background, on the right side of the painting, there is a portrait of a genuflected gentleman who, with his head tilted and his hands clasped to his chest in an act of faith, appears almost in the center of the composition: the lace and gorget, the typical cape and the flowing hair on the nape of his neck are all elements that take us back to the 17th century. Next to him, toward the right margin of the painting, are two female figures, one of whom is young and blond and seems to be singing, and the other, less young and brunette, with her head veiled and her hands clasped in prayer, who seems to be murmuring those songs or prayers that can be read on the score supported by the graceful angel on the left, in the foreground. The first woman appears opposite and largely hidden by the figure of the gentleman, while the profile of the second is enough to introduce her into the scene. Langelo has an unprecedented sensuality that stands out to the eye: he is portrayed in profile with his leg protruding from the snow-white pink robe and with an uncovered shoulder revealing a pearly, nivea skin; the score is held up by his very sweet and delicate hands that make him even more seductive; even the wings are depicted with attention to detail, bringing to mind the Flemish art, as well as the still life that is described in every detail. In the center, or rather more off-center on the right, is a religious man in a dark habit kneeling before the upright figure of the saint who dominates the vast field of the canvas, dressed in the same manner as he unfolds the page of a book offering Gospel words. On the upper left, above a nimbus supported by two little angels are depicted Jesus blessing and at his St. Paul and St. Peter.

|

| Michele Ragolia, Saint Gaetano of Thiene Gives the Rule (1666; Polla, Christ the King). |

The subject of the painting is the presentation of a noble family to the Redeemer with the devout symbolic intercession of a saint, which respects the custom and taste of feudal nobility. The scheme depicted here is reminiscent of that of the illustrious family in Titian’s Pesaro altarpiece though with differences: the Venetian painting is dominated by the figure of the Madonna and the intermediaries St. Peter, St. Francis, and St. Anthony, while in the lower right, the patrons do not take away space from the composition since they are seen, with the exception of the gentleman covered by the mantle, with few elements of the person in secondary planes or in a marginal foreground.

In the Polla altarpiece much of the background is taken up by the foreshortening of a town in which Polla is recognized in the 17th century, with a bell tower with three recessed bodies and a dome surmounted by a lantern that belong, almost certainly, to the church of San Nicola dei Latini, depicted as it was at that time. Lartista betrays the freedom he allowed himself in representing the landscape by arranging the elements in a different orientation.

|

| Tiziano Vecellio, Pala Pesaro (1519-1526; oil on canvas, 478 x 268 cm; Venice, Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari) |

The noble family represented with the background of Polla should be placed in relation to the town, giving reason to the local tradition, which sees in these characters the family of the Marquis Villano, feudal lords of Polla at that time, and in the intercessor saint, Saint Gaetano. Indeed, we know that in late 1625 Giovanni Villano, after the death of his wife, retired to Naples among the Theatine fathers of the convent of San Paolo Maggiore, where he died two years later, renouncing all feudal privileges in favor of his younger brother Francesco Antonio, who thus became the new marquis of Polla. This news is confirmed in the Bulifon’s Newspapers of Naples, in which we read that “on the 25th of the same pleasantly ended his days of the year P. [ ] Villano, who shortly before with magnanimous refusal had deposed, to serve God, the marquisate of Polla.” The scholar Vittorio Bracco asserts that the painting can be dated to a period not earlier than 1625 and not later than 1627, succeeding in identifying the genuflected nobleman as the new feudal lord, the kneeling religious as Marquis Giovanni Villano already dressed in the Theatine habit, while the standing intercessor, wearing a black cassock habit, as Saint Gaetano da Thiene, at that time only Blessed because his canonization as a saint was done by Pope Clement X in 1671. It is evident that the depiction of St. Gaetano, with his black robe, gaunt face, short beard, and high forehead, derives from the circulation of engravings with his likeness, as prints of the Vida de San Cayetano written in 1619 by Juan Bautista Castaldo were certainly circulating at the time. The two female figures have been recognized as the marquis’ wife, Emilia, and sister, Lucrezia.

As for the dating and the name of the author, the discourse changed thanks to deductions based on objective findings made by Alfonsina Medici. Since Michele Ragolia sojourned in Polla in 1666 to paint as many as forty canvases for the majestic church of SantAntonio commissioned by the Franciscan Observant Fathers, it is almost certain that he produced the work in question in the same year. What proves the attribution is the discovery in the church of San Paolo Maggiore in Naples, of an almost identical canvas with the only variation in the landscape, which in the Neapolitan canvas depicts the pronaos of an ancient temple. Carmine Tavarone has carefully studied the two canvases, based on a historical reconstruction of the activity of the Palermo painter who, before arriving in the Vallo di Diano, had worked in Naples. Attributing the Neapolitan canvas, which was painted in 1643, to Massimo Stanzione, Tavarone states that the Pollese canvas is certainly later and that the author may have been Ragolia. Therefore, the altarpiece was commissioned by Giovanni Villano’s brother Francesco Antonio, probably to fulfill a vow after the plague of 1656. Vega De Martini, after examining the two paintings, also confirmed that Ragolia’s style does not differ much from that of the Villano Altarpiece.

The Villano Altarpiece plays an important role in the history of Polla because in this work, excellently restored in the workshops of the Certosa di San Lorenzo in Padula, there is the only evidence of what the town looked like in the 17th century before it was destroyed by the earthquakes of 1694 and 1857. The Pollese background unites the canvas even more with the meaning intended to be expressed in it: the cession of the fiefdom from one brother to the other and the blessing that the first asked on the other and on the remaining family at the moment it took possession of the town.

The painting is easily introduced into the historical panorama and the moral climate introduced by the Counter-Reformation, and this is emphasized by the tilting of the young nobleman’s head, emphasized by his pathetic gaze. The altarpiece also confirms the religiosity to which the family in question was subject, for Giovanni’s daughter, Beatrice, demonstrated her pious disposition from an early age, deciding to take vows in the Dominican order of friars under the name of Sister Maria, and established a new community entitled Divine Love in Naples. Marquis Giovanni sent letters to his daughter from Polla between August and October 1625 in which he expressed his intention to retire to the Neapolitan convent of San Paolo Maggiore after the death of his wife Emilia. Observation of the painting shows that the exterior of the church of San Nicola dei Latini is different from what it looks like in its present state, which leads one to suppose either a previous intentional demolition of the dome, though unjustifiable, or a collapse that occurred during one of the two earthquakes of September 8, 1694 and December 16, 1857 that struck the entire area of the Vallo di Diano, including Polla.

Among other things, during the 1857 earthquake, the church of Santa Maria dei Greci also collapsed, in which there were “in the suffix of the said church nineteen oil paintings representing various mysteries and miracles of the Virgin Mary. Lautore was M. R. F. 1684, who is known to have been a certain Sicilian Michele Ragolia, who at that time left various paintings in Polla,” as can be seen from the July 5, 1811 inventory of all the paintings and bas-reliefs existing in the parish church of the said church. Another anomalous element emerges from the examination of the canvas: the bell tower to the right of the dome of St. Nicholas, belonging to the older church, was behind it while now it is in front of it. This can only be explained by a hypothetical 18th-century addition of the oratory, attested by the interior inscription, on the area formerly occupied by the bell tower. In the painting one can also catch a glimpse of a section of the walls, recognizable by the crenellated crowning, at the foot of the dome and bell tower of the church of St. Nicholas of the Latins, which constituted the old curtain wall dating back to the first foundation of the settlement, erected at the time of the Normans in the 11th century, and of which a few towers converted into dwellings and a few gateway arches exist to this day. But by the seventeenth century, as the picture shows, the township had outgrown its original perimeter, lowering itself down the hill.

A further confirmation that leads to attribute the altarpiece to Michele Ragolia is the glimpse of Polla in the background on the right because later the painter would try his hand at creating a view, admirable from an aristocratic living room of a Neapolitan palace, more precisely in theInternoda collezionista, painted in 1670. This may have been the prelude to later commissions in the Neapolitan city, as well as the capital of the Kingdom and a strategic political and cultural center where he had already held important commissions. The considerable size of the altarpiece suggests that it was made on site, evoking a time and society long gone.

Lartista does not seem so foreign to the major artistic currents established in Neapolitan painting, ranging from the Caravaggesque to the Carraccesque. Indeed, some elements recall several paintings by well-known Neapolitan artists: the Saint Gaetano is reminiscent of the one in Stanzione’s frescoes (now reduced to a few fragments) in the church of San Paolo Maggiore in Naples; the bunch of lilies, at lower left, recalls the similar detail in a painting by Mattia Preti depicting the Virgin between Saints Gaetano and Francesco da Paola, found in the church of Santa Barbara in Taverna, in the province of Catanzaro; Saint Gaetano’s necklace in the Polla painting is double-turned, while in the Preti’s it is depicted with only one turn.

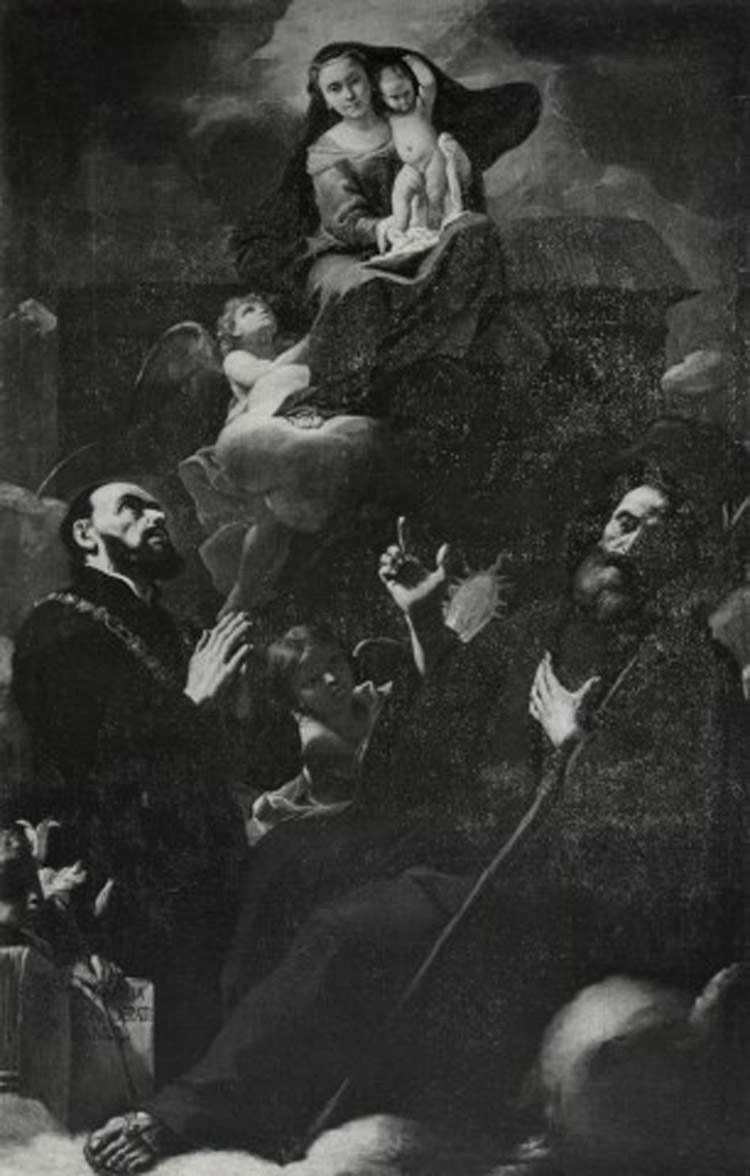

|

| Mattia Preti, Madonna and Child between Saints Gaetano da Thiene and Francesco da Paola (mid-17th century; oil on canvas, 233 x 160 cm; Taverna, Santa Barbara) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.