If one wanted to find some trace, some fragment of the ancient history of Savona’s Palazzo del Monte di Pietà (“one of the first in Europe,” as tourist guides take pains to point out), one would struggle to notice it on the outside, on the nineteenth-century facade of the building that in 1479, at the behest of Savona’s pope Sixtus IV, became the seat of the institution: one needs to enter and visit what is now the Museum of Ceramics of Savona, opened in 2014 after the building underwent extensive restoration, and run today by the Ceramic Museum Foundation, which has meritoriously based its organizational structure on a close-knit group of skilled and enthusiastic young people. It is necessary to wander through its rooms, among the display cases that tell the centuries-long history of the art that has given luster to this strip of western Liguria, to stop in front of a frescoed wall, to observe the detail of a window, to look up and linger over the decoration of a vault. At some point, one will encounter a hall with a ceiling decorated by one of the most important Ligurian artists of the second half of the 17th century, Bartolomeo Guidobono, another illustrious son of the city. An artist with a temperament that was “modest, shy, meditative, introverted,” as Gian Vittorio Castelnovi had written, a temperament that allowed Guidobono to keep in check “every fantastic extravagance” and induced him “to willingly observe.” and it is certainly far from any eccentricity that his fresco is clear, balanced, animated, perhaps not so innovative, but certainly of great effect, mindful of the solutions that Pellegrino Tibaldi had adopted in Bologna, at Palazzo Poggi, perhaps with the mediation of those among the Ligurians who knew Emilian art well. However, there is a peculiarity that only here, only at the Museum of Ceramics in Savona, is it possible to observe: in the display cases arranged under Guidobono’s vault, there are ceramic plates that were painted by him. Or rather: that are attributed to him, since there are no ceramic objects that have his signature. But we are sure that the artist provided his designs to the workshops from which the plates that can be observed today at the Museum of Ceramics came out, we know that Bartholomew came from a family of ceramists, we recognize in certain plates his style. And so it cannot be ruled out that he himself had also painted something that we can admire today inside these display cases.

It is not often that we find that an artist who was successful in the art of fresco painting might have devoted himself to more everyday production. Let alone see his everyday objects displayed under a ceiling decorated by his own hand. In the room, the panel reads “istoriato barocco”: this is the name by which the type of decoration that was in vogue in the seventeenth century is known. The repertoire was drawn from mythology, from ancient stories: the loves of the Olympian gods, epic scenes of battles between knights, processions of cherubs and cupids, encounters between ladies and gentlemen. One of the greatest poets of the seventeenth century, Gabriello Chiabrera, may have been looking at one of the cups he had in his home, painted with scenes similar to those the visitor observes in the halls of the Ceramics Museum, when he composed the “Invitation to Drink,” perhaps his best-known lyric: “Serene and clear auras / spirano dolcemente, / and the dawn in the east / rich with lilies and violets appears. / On the hermit bank / along the lovely brook of this grassy shore, / O Filli, to drink invites / ostro vivo di fragorosa strawberry. / Among my dearest cups / bear the most beloved, / that where thunderbolts / Amor over a delfin the sea gods.” Here they are, the sea gods, appearing even among the plates in the room reserved for baroque historiated: the chariot of Neptune advances through the waves on a plate attributed to Bartolomeo Guidobono. And if anyone thought that for the artist this production was a kind of fallback, they would be wrong. The people of Savona had no difficulty in recognizing the goodness of his ceramics, in considering them objects of value. As early as 1738 the guild of the pignattari could affirm that “either such sculpture and painting that is seen in said vases is the work of master chisel and brush [...] or [like] many [that] even today are preserved by citizens painted by Guidobono accredited Savonese Painter, and in that case the estimation of such vases comes from the brush of those who painted them and not from those who made them.”

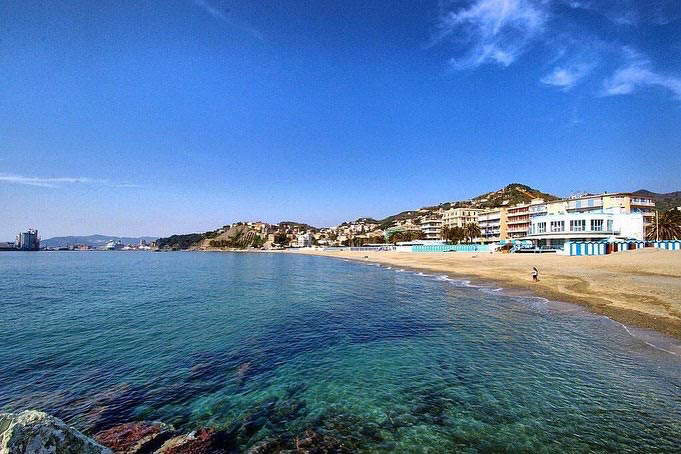

For an eighteenth-century Savonese it was perfectly normal for a great and esteemed artist to collaborate with potmakers to decorate plates, dishes, cups, and coolers. And so it would be for centuries: pottery here was never a secondary art. Then, over time, the workshops moved and pottery, after dying out in Savona, was rekindled in Albissola Marina, but the consideration that this land has for its art has never diminished. Ceramics, here, can be seen, eaten, breathed, lived. Ceramics compose a universe that is made up of kilns, small factories run by the same families who hand down the craft from generation to generation, tiny artisans’ workshops, ateliers where artists come from all over the world to learn how to shape the earth, shops where to buy authentic products, because in Savona and Albissola there has never been that uncontrolled proliferation of stores reselling objects of dubious interest, as well as of dubious provenance, that has turned many historic centers into chaotic souks for the use of tourists. Here it is the opposite. In Savona, finding a pottery resale is anything but a foregone conclusion. Albissola Marina, on the other hand, offers more, while keeping its authenticity intact: often, those who sell are also those who produce. And entering a store, one will also realize just how transversal pottery is in these parts: those with spending power go for large vases, one-of-a-kind pieces, elaborate glazed sculptures, and whimsical coffee services designed by important artists, but for just a few euros one can take home a saucer, a hand-painted bowl emptier, or a figurine for the nativity scene.

The

The The Museum of Ceramics in

The Museum of Ceramics in The Ceramics Museum of

The Ceramics Museum of The Museum of Ceramics of

The Museum of Ceramics of The Museum of Ceramics of

The Museum of Ceramics of

That’s right: the nativity figurines. In Albissola Marina there is also a tradition of poor, popular ceramics. That of the nativity scene is an excellent example, because alongside the lofty tradition that satisfied the demands of the wealthy (think of Anton Maria Maragliano’s extraordinary wooden statues), much humbler forms of expression developed over the centuries. humble, such as that of the “macaques” of Albissola, the nativity figurines so called because of their clumsy and ungainly appearance, which experienced their heyday at the beginning of the twentieth century. “Horrible,” Giuseppe Cava, the “Beppin da Ca’,” who was Savona’s greatest dialect poet, would have called them: during a walk at the Santa Lucia fair, he could not understand how, in his opinion, the art of the nativity scene had gone to such degradation. “The majority of the shepherds, offered for sale, come from the artisans of Albissola and are horrible,” reads one of his stories published in the collection Vecchia Savona. “Monsters that of the old artistic figurines possess nothing but semblance. Two black dots to mark the eyes and a red line to trace the mouth, on gibbous bullets that want to be heads. The bodies of figurines and presents to be offered to the Child Jesus, carried on shoulders or in baskets of beautiful chrome yellow, are a wrath of God. [...] I fear that the ruin of such an industry of ours is now irremediable. It would take a group of patrons and artists to devote themselves to it with love and constancy. But where to find willing people willing to lose time, effort and money? In the meantime, foreign production will become more established and we will see a not inconsiderable source of income for our clay artisans exile elsewhere. So be it!” Cava could not have imagined that, a century later, macaques would become sought-after objects, and even valued by an association, Macachi Lab, which promotes the culture of the Albissolese folk nativity scene.

With such strange and coarse figurines, an artistic genre that had been declined in magniloquent forms by the greatest artists thus returned to the simplest element: the earth. Or rather: the “tærra bÅnn-a” as we say here, the “good earth,” the clay that is accumulated in squared masses inside the workshops waiting to be handled, folded, touched, caressed, massaged by those who will give it a shape, after a thoughtful and passionate workmanship. Guido Piovene, introducing a 1963 book dedicated to the protagonists of modern ceramics, wrote that ceramics is “the most universal and ancient art, the result of a human instinct that is reproduced everywhere at the dawn of civilization, at the same time as that of cultivating the earth, and making ceramics is also a way of cultivating the earth that arises simultaneously with the other, as if spading it and plowing it and shaping it with the hands were two complementary impulses. Therefore, each pottery, if it participates in the taste of the century that produced it, is also older than itself.” Primitive art, which comes from the earth and is enlivened by the decisive intervention of fire, which binds with inseparable knots the human being to the primordial element, art that sums up the characteristics of sculpture, painting and even architecture, art that requires time, profound knowledge, manual dexterity, patience, determination, art that also requires being willing to engage in duels with deaf matter.

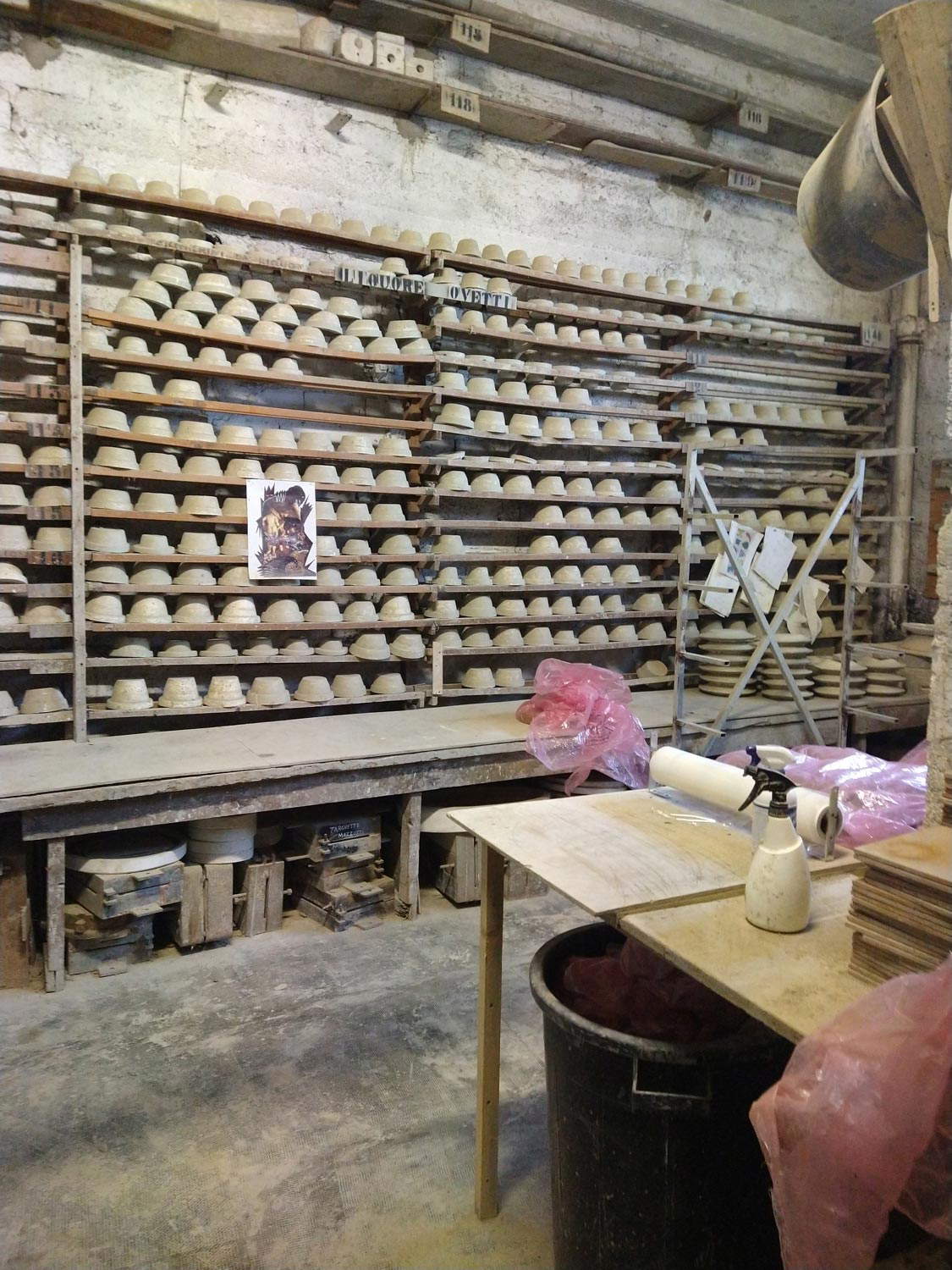

And in Albissola it may happen that, wandering through its alleys, one enters a workshop (they are almost all in the historic center) and sees some craftsman at work, intent on shaping the earth near where the finished objects are sold. One might enter one of these workshops, lined up neatly facing the sea, or hidden in the tangle of downtown streets next to Pozzo Garitta (where Fontana’s workshop was located), if only to enjoy the spectacle. Or to listen to the tales of those born in the midst of ceramics, those who carry on a family tradition, those who have worked elbow to elbow with the greatest artists. In the center one comes across Ceramiche Pierluca, founded in 1989 and specializing in traditional styles: just a glance at the tidy shelves is enough to get an idea of four centuries of Savona and Albissola ceramic history. Not far away, there is Ceramiche Viglietti, which has also set up a section of contemporary ceramic sculpture and declines tradition in a wide variety of forms. Walking along Aurelia, one finds oneself in front of the futurist building, designed in 1938 by Nicolaj Diulgheroff, of Ceramiche Mazzotti, while a few steps away one will visit the headquarters of the almost eponymous Ceramiche Giuseppe Mazzotti 1903, where the established the Futurist style (the greatest Futurist ceramist, Tullio d’Albisola, was named Tullio Mazzotti and it was he and his brother Torido who founded the manufactory), and where there is also a small museum collecting works by artists who have passed through here: from the street, in the garden, you catch a glimpse of the most famous work, Lucio Fontana’s Crocodile, the large life-size reptile modeled in 1936 by a Fontana who had just begun to investigate the potential of ceramics. Impossible, then, not to stop at Ceramiche San Giorgio: having crossed the threshold one immediately breathes in the scent of earth mixed with that of the brackish, and one feels almost overwhelmed by the chaotic atmosphere of the atelier founded in 1958 by Eliseo Salino together with Giovanni Poggi and Mario Pastorino, and today run with unwavering passion by a Poggi more than 90 years old, but still eager to tell sixty years of stories to anyone who passes by and is lucky enough to meet him. The photos hanging on the walls depict him with some of the artists who have worked in his workshop, most notably Wilfredo Lam and Asger Jorn, almost two of the workshop’s tutelary deities. These are all places where the line between sales and production is blurred. Sometimes all you have to do is walk down a flight of stairs to see two totally different environments: above, showcases for display. Below, a kiln with people busy molding, painting, preparing for firing. Sometimes it even happens that a dirt artisan ends up in the middle of the tourists who are deciding what to buy. A Dantean journey in a few square meters. What other places grant similar experiences? Where the relationship between production, processing, sale, low products and high products is just as close, inseparable?

The

The The

The The

The

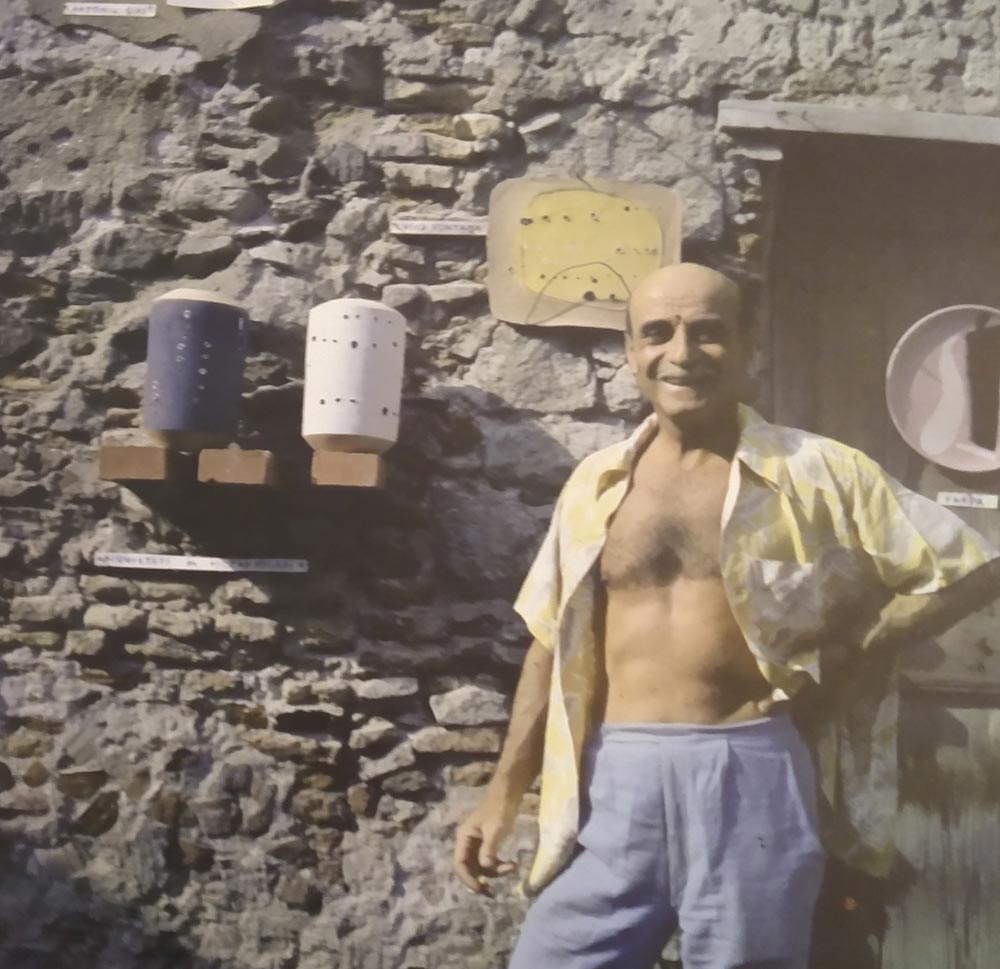

The earth, after all, is a humble element. And it forces even great artists to remain humble. Every guidebook on Albissola ceramics does not fail to repeat the names of the greats of recent art history who have passed through here. The list is long: Lucio Fontana, Pinot Gallizio, Arturo Martini, Sergio Dangelo, Aligi Sassu, Piero Manzoni, Giacomo Manzù, Agenore Fabbri, Wilfredo Lam, Karel Appel, and the list could go on and on. Almost all of them are represented at the MuDA Exhibition Center, the Museo Diffuso Albisola, where one is enchanted by the light emanating from the ceramic panels Fontana made for the Conte Grande, and where one wanders among small and large ceramics by Lam, Jorn, Fabbri and many others that are displayed in rotation. Other pieces can be admired in the other museums in the area: again at the Museum of Ceramics in Savona, or at the Manlio Trucco Museum of Ceramics in Albisola Superiore, another telling of the history of ceramics up to futurism and including pieces by Arturo Martini, Francesco Messina, and Lele Luzzati. Then there are the mosaics that enrich the Lungomare degli Artisti, a fascinating one-kilometer promenade in Albissola Marina, inaugurated on August 10, 1963, and dotted with artworks specially created by twenty artists who may not have even been aware that they were participating in a public art project that was unprecedented, even in the rest of the world. Perhaps Fontana realized this, who after the opening wanted to install three of his Spatial Concepts along the route. Asger Jorn, on the other hand, did not participate in that endeavor (although a mosaic from one of his works was placed on the Artists’ Promenade in 1999), but his figure has a charm all its own: the Dane who lived inside a tent, the Viking who celebrated ugliness as a kind of antidote to indifference, the artist who based his quest on total freedom, spontaneity, imagination, and the rejection of all conventions. “Our goal,” the artist wrote in 1949 in his Speech to the Penguins, “is to free ourselves from the control of reason, which has been and still is what the bourgeoisie has idealized in order to seize control of lives.” Jorn was the only one who put down roots here, who wanted to build a house that was not just a dwelling, but a hymn to his idea of art, a temple of creativity, and today a visit to what has become the Jorn House Museum, with an adjoining studioî center, is a must on a journey inside Ligurian ceramics.

Another name that comes up often is that of Arturo Martini. At the Museum of Ceramics in Savona there is a portrait by him of his daughter Nena, first exhibited at the Promotrice in Turin in 1930 and immediately a wide success, so much so that it was often replicated. It is a portrait that is surprising in its vividness: the little girl is caught in a natural pose, her mouth slightly open, holding her head with one hand, appearing listless, almost sleepy. The breath of life that animates this enthralling image also emerges from a letter in which Camillo Sbarbaro, writing to Oscar Saccorotti, recalled a visit he had made to Martini’s workshop in Albissola: here Sbarbaro caught the artist at work on a work that must not have been so different from the one now on view in the museum. “There is [...] an art that does not immediately touch me like yours and yet, I feel, exists,” Sbarbaro wrote to Saccorotti. An art that is “more crafty, less appreciable if one does not feel the recalls and resonances with which it is rich; if one does not put oneself from the point of view from which alone it is in focus. But that is not why my mistrust falls, and I do not applaud until I come to be satisfied that it is art suffered as need. Fortunately I happened, for example, one summer with the overbearing sculptor that is Arturo Martini. I found him in an urn in Albisola who was, as it were, giving birth to one of his terracottas: the bust of a little girl with curled braids, a beret and a dreamy shyness in her already serious face. The image was still blind. ’Now I’m going to wake her up,’ Martini told us. That crock was alive to him; not from the sentence alone and the voice could be understood, but from the way he handled it: alive and in need of regard. And when he had opened her eyes, looking at her from a distance: ’Her name is Andreina. She is twelve years old. She comes out now from the nuns... ’. Every detail became true as soon as it was enunciated; it fit; it illuminated the work, put it in its air.”

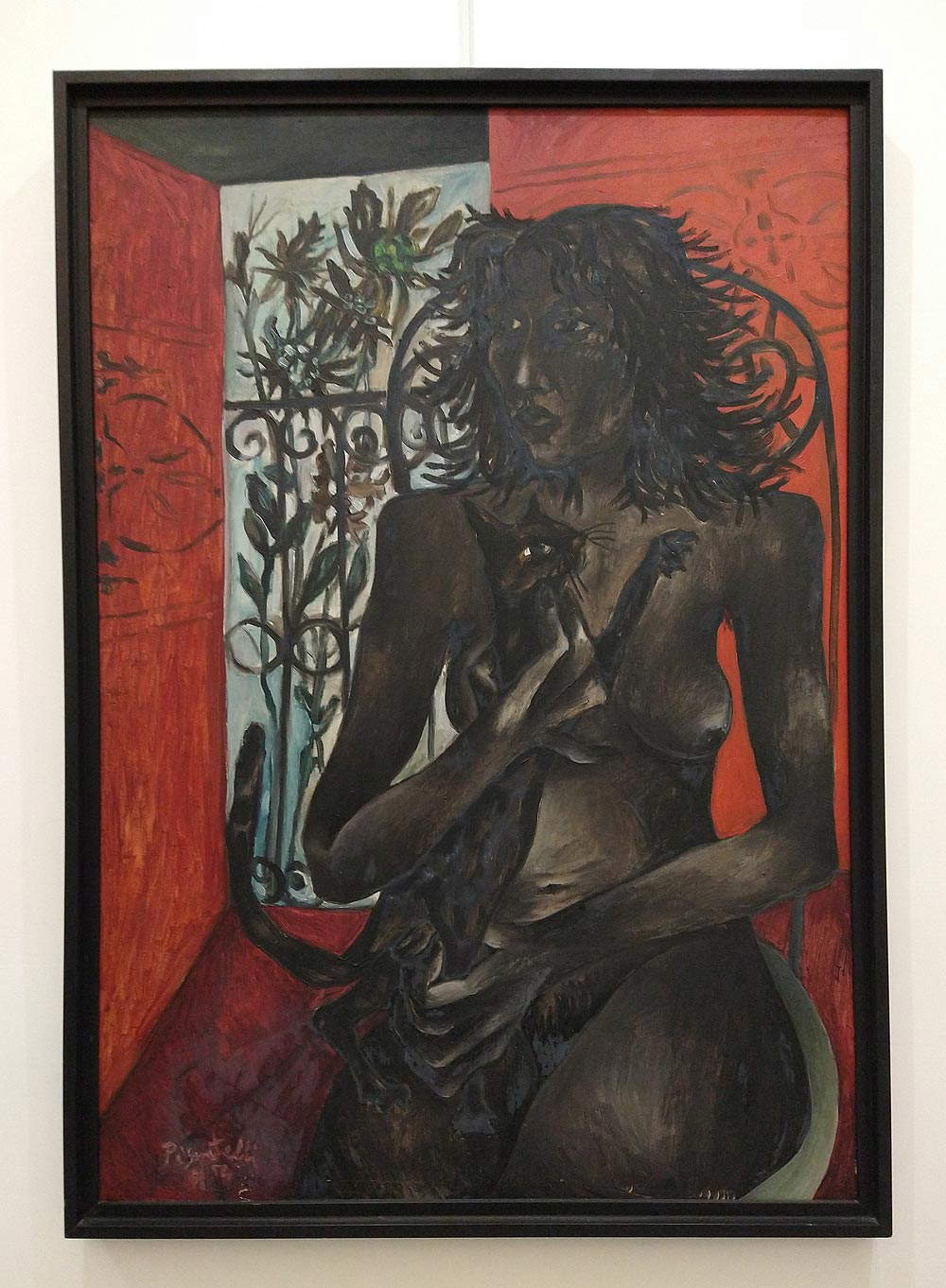

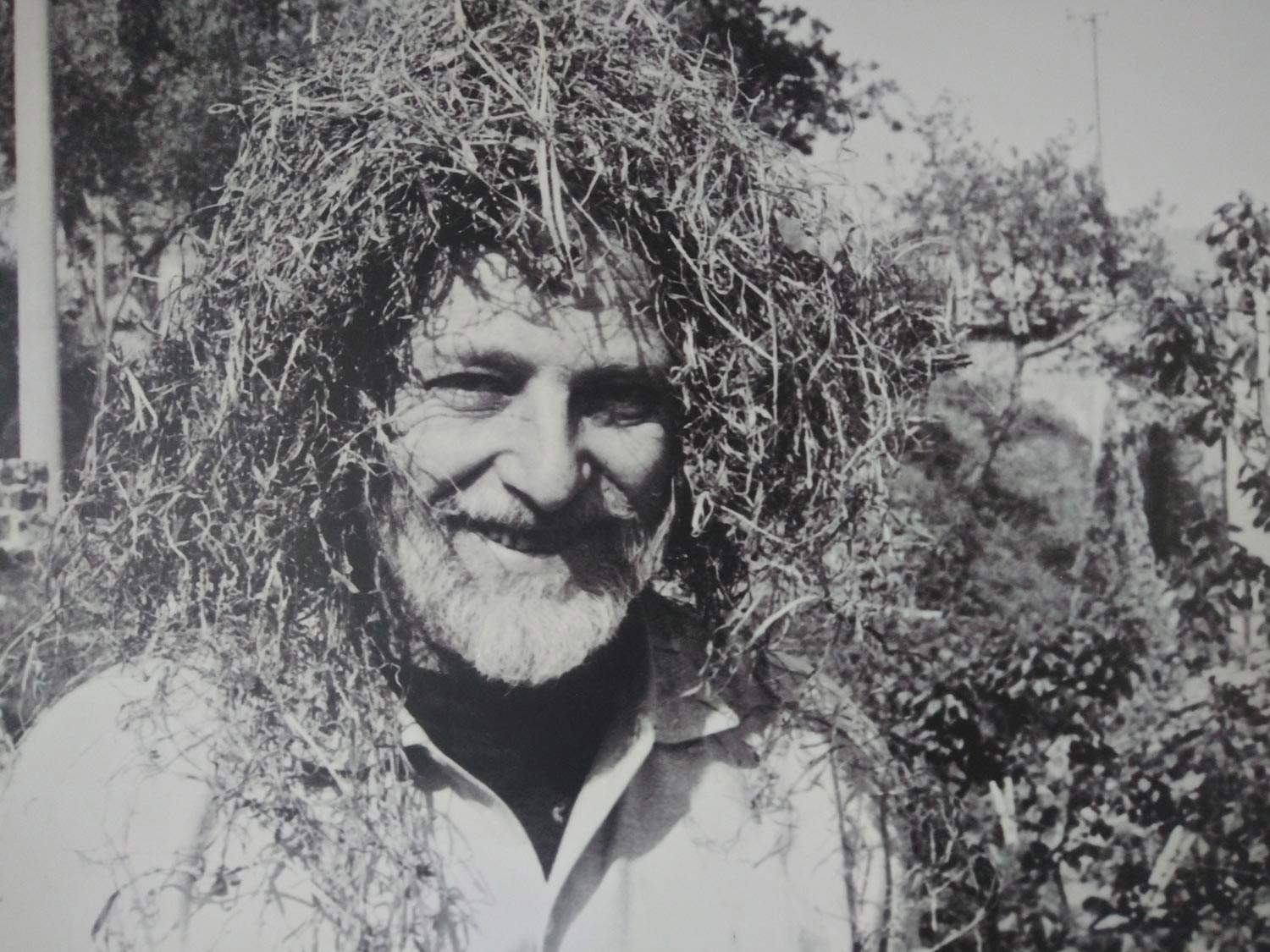

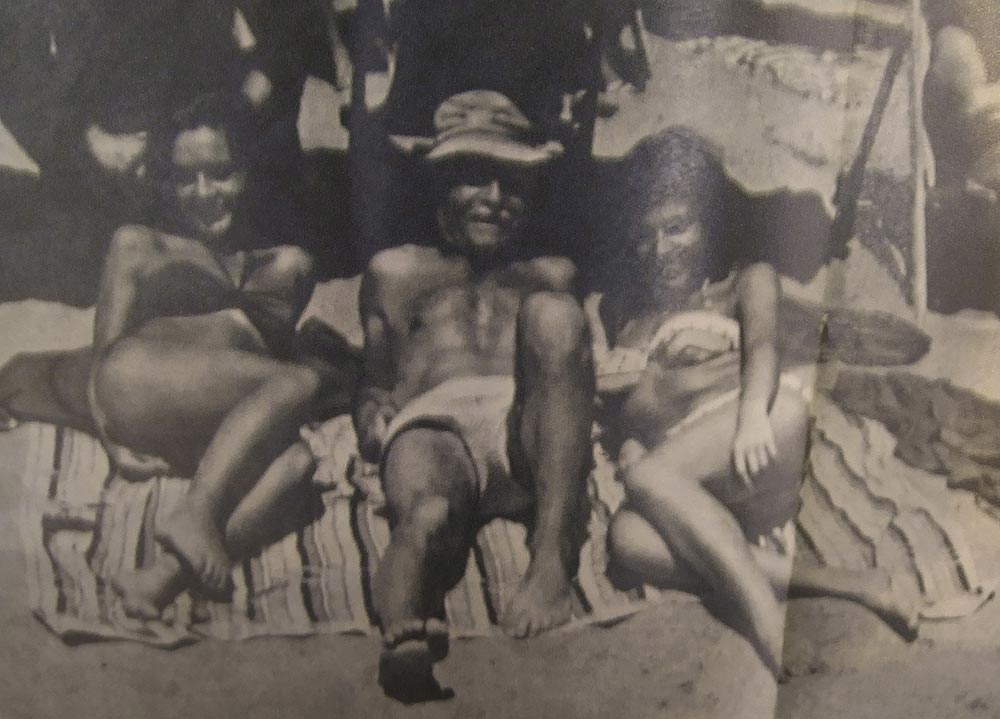

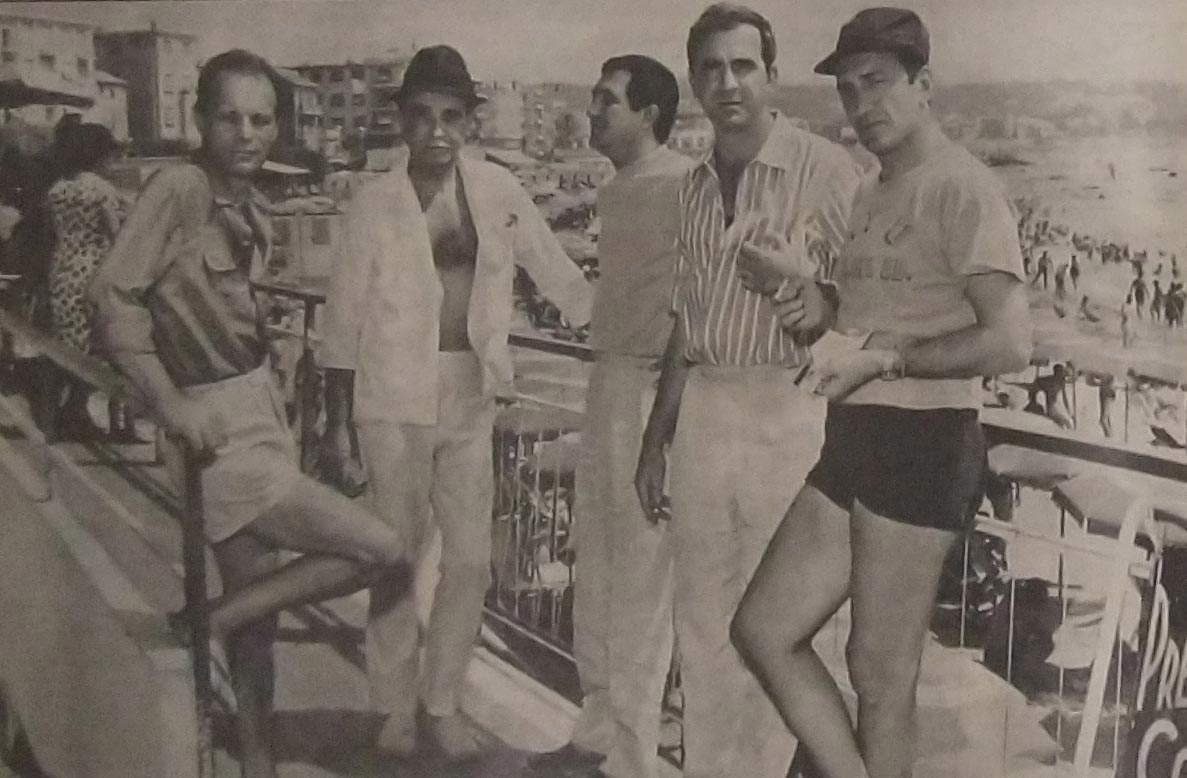

It still happens, going around Albissola Marina, to hear anecdotes like Sbarbaro’s. No need to search archives or libraries: for many who lived through that season, the memories are still alive. Sometimes the flame is kindled by a photograph attached to the wall of a restaurant or a store, other times it is enough to walk down the street, or look at that beach that was “not a beach like any other” for Milena Milani, another extraordinary figure who linked her name to these lands (one of her novels is also set in Albissola Marina, and the works that belonged to her and her companion Carlo Cardazzo’s collection are on display at the Savona Art Gallery). “There are the intellectuals, painters, poets, novelists, essayists, philosophers, sculptors, critics, art dealers, ceramists, a whole elite that makes Albisola a unique place among Italian beaches,” he wrote in 1960. "Do not think that with all these highly qualified personalities, Albisola is a boring place, where people do not know how to have fun. Here, too, there is dancing, there are orchestras, there is uproar, misses are elected; however, the atmosphere is different, because even normal people, the so-called vacationers, are intoxicated by the bacillus of art, they participate in exhibitions, go to conferences, listen to the reading of poetry. [...] The people of Albisola, as a rule, are not frightened by the most advanced art, or rather, they do not even flinch anymore, they have exceptional taste, they accept paintings of a single color, or the strips of paper, twenty, thirty meters long, like those of Piero Manzoni, a descendant of the writer; Fontana’s holes and cuts are now a matter of course, like his last sculptures, huge clay boules, on which the extraordinary artist lashed out with his fists (rebellion? desperate restlessness? certainly today’s life leads to these unsatisfied forms); the people of Albisola accept paintings and ceramics by the Dane Jorn, one of the most internationally quoted artists, and to whom Mayor Ciarlo, who is also a collector, has granted honorary citizenship (with him, Fabbri, Fontana and Sassu had it)."

The

The The

The

It is still natural for the people of Albissola to talk about Fontana, Jorn, Sassu and all the others as if they were talking about old friends. In Albissola there are no barriers, you do not perceive that mixture of reverential awe and distance that, with few exceptions, anywhere else in Italy is felt when someone explains the work of an artist, perhaps even linked to the area. The tærra bÅnn-a united everyone, there was no distance, the inhabitants were accustomed to artists, their extravagances, and galleries (Milena Milani wrote that in Albissola Marina, proportionally, there were more than in Milan), also because they frequented the same haunts as the locals. And even today there is a similar air, there are still prominent artists who frequent the workshops of Albissola Marina: Ugo Nespolo, Giorgio Laveri, Vincenzo Marsiglia, just to mention three names at random. Or the Savonese Sandro Lorenzini, who recently had the honor of a major solo exhibition at the Museum of Ceramics, which was filled with his works, giving the public a narrative of fifty years of impetuous and lively career. And then here ceramics, along with the sea and beaches, great art, and evenings spent in the clubs along the waterfront or downtown, is still part of a lifestyle irreproducible elsewhere. However, there is no longer that unrepeatable community, no longer that congerie so varied and so dense that moved the Albissolese summers of the 1950s and 1960s. Perhaps it was a miracle. So much so that even today one wonders how it was possible that in such a peripheral context, so small, so hidden, a community sprouted and grew that produced some fundamental events for the arts of the 20th century. No other ceramics center in the world has experienced a season like that, not even in those cities where ceramics structures an economic and educational system. How was it possible? Martina Corgnati, in her contribution on Giuseppe Mazzotti Ceramics, tried to give an answer: “Singular alchemy of provincialism and cosmopolitanism, simplicity and open-mindedness, productive capacity and sensitivity to the renewal of forms. The catalysts of this extraordinary process, which far more sustained institutions and seemingly far more favorable situations have failed to activate, are to be found first and foremost in the factory.”

It was, in short, a mélange of elements that is impossible to find elsewhere. The artists arriving here found a vibrant productive fabric that had centuries of history behind it, they found inhabitants well disposed toward them and indifferent to their eccentricities, they were seduced by a lifestyle that only the resorts on the Italian coast can offer. That was then the season of seaside holidays: think of those communities of artists and literati who gathered every summer, thinking of places not too far from Albissola Marina, in the Cinque Terre, on the Golfo dei Poeti, in Bocca di Magra, in Forte dei Marmi, in Viareggio. It is a time in history that will not return, a recent chapter in a tradition that has produced so much throughout the centuries. And to understand why ceramics here is a founding element of the way of life, it is not enough to be carried away by memories, writings, stories, images. One needs to go. You need to see for yourself. Breathe in the sea air of these cities. Be caressed by the wind on a waterfront evening. Meet the locals, talk to them, go out with them for lunch or dinner, chat about more and less. Or go to any bar and listen to them. See the works inside museums and inside workshops. Touch an old photograph. Looking at the sky of Albissola the sky that changes with every moment, as Milena Milani wrote, “clouds pass and pass again, and when the sky is clear, it is a beautiful blue, charged, inviting.” Only then can one try to understand why ceramics here is like air. And why every time a local tells even the most trivial and insignificant story having to do with ceramics, his eyes light up.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.