by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta, published on 07/11/2020

Categories:

Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

At MAMCO in Geneva since 1994 is the faithful reconstruction of the apartment of critic and collector Ghislain Mollet-Viéville, which transports a piece of the fervent Paris of the 1970s to Switzerland.

There are not many museums inside which an entire apartment can be found. One of the best-known cases in Italy is the so-called Albini Apartment located on the top floor of the Palazzo Rosso Museum in Genoa: the great rationalist architect Franco Albini set it up in the 1950s as the home of the then director of the Civic Museums of Genoa, Caterina Marcenaro, who would use it both as a home and as a representative space. When we are faced with cases like these, it is usually because there is a very solid relationship between the museum and the inhabitant of the apartment: that is what happens at Palazzo Rosso and that is what happens in another very unique case of an apartment inside a museum, that of the art critic and collector Ghislain Mollet-Viéville (Boulogne-Billancourt, 1945) who finds space on the third floor of the MAMCO (Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain) in Geneva, Switzerland. The main difference between the Albini Apartment at the Palazzo Rosso and L’Appartement at MAMCO, beyond the nature of the works housed there and of course the style of the furnishings, lies in the fact that the one at the Palazzo Rosso was actually used, while the one at MAMCO is a faithful reconstruction of the apartment in which Mollet-Viéville lived, from 1975 to 1991, at 26 rue Beaubourg in Paris.

Mollet-Viéville still likes to call himself an “art agent,” that is, a kind of commercial agent who, however, instead of promoting products of another nature, promotes works of art, and specifically minimalist and conceptual art, through lectures at museums, universities, and companies, through articles in the press, through the organization of exhibitions, and many other ways. His own apartment had been central to his activities, since it was regularly opened to the public and often hosted exhibitions of the artists Mollet-Viéville intended to promote. This extravagant collector’s idea had a definite basis: to do what museums did not do. And why is quite clear: in a 1992 interview, Mollet-Viéville recalled that, in 1975, he hosted an action by one of the most controversial and subversive artists in Paris at the time, the Romanian André Cadere, around the concept of “established disorder.” The performance, Mollet-Viéville recalled, “not without its own logic ended with a brawl triggered by the arrival of a dragnet of rock musicians in the apartment. A museum would have had a hard time organizing such an action, that is, presenting the most advanced peaks of thought on a given problem and simultaneously its lowest manifestation, in real time.” For Mollet-Viéville, places of institutional culture have limitations, chief among them the fact that the public approaches the artwork according to the canons of the exhibition, which end up “trapping the works,” with the consequence that visitors often struggle to understand the works and actions of artists who step outside certain canons we typically associate with art.

Then, in 1992, the move to his new apartment, at 52 rue Crozatier in the Bastille, a home that, unlike the one in Beaubourg, does not see the presence of even one work of art: “at the moment I have nothing to show and I am showing it,” as per the title of one of his 1985 exhibitions. The collection that was part of the Beaubourg house thus ended up at MAMCO in Geneva since the museum’s opening date of 1994 (a date that coincides with the opening of L’Appartement to the public), and then between 2016 and 2017 the works were largely acquired by the Geneva museum. It is a collection of 25 works by artists from the first generation of minimalist art (Donald Judd, Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Daniel Buren, John McCracken and others) and conceptual art (such as Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, Lawrence Weiner, Robert Barry, On Kawara, André Cadere). So, on the one hand, artists who propose an art totally untethered from any intent not only figurative but also narrative, founded on elementary forms, while on the other hand artists who challenge conventions with works whose idea takes on greater relevance than the aesthetic content.

|

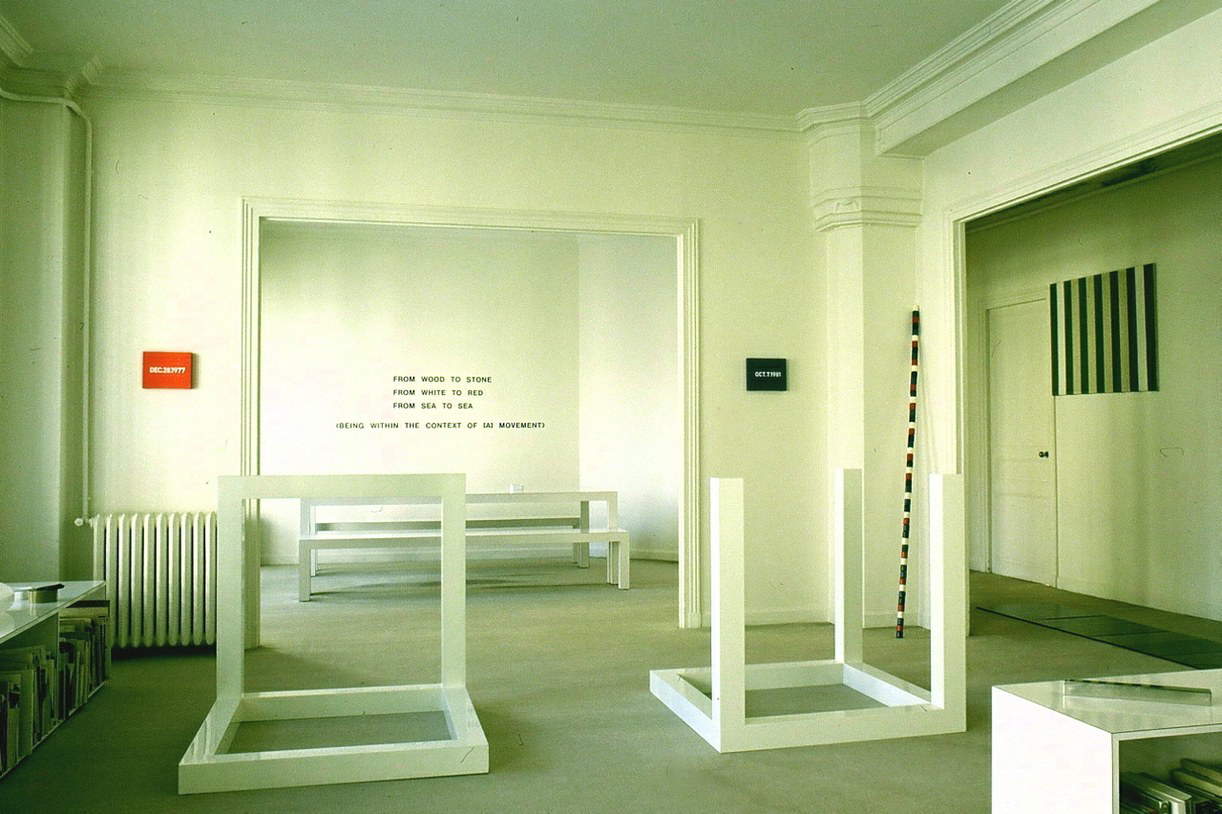

| The rue de Beaubourg apartment in the 1970s |

|

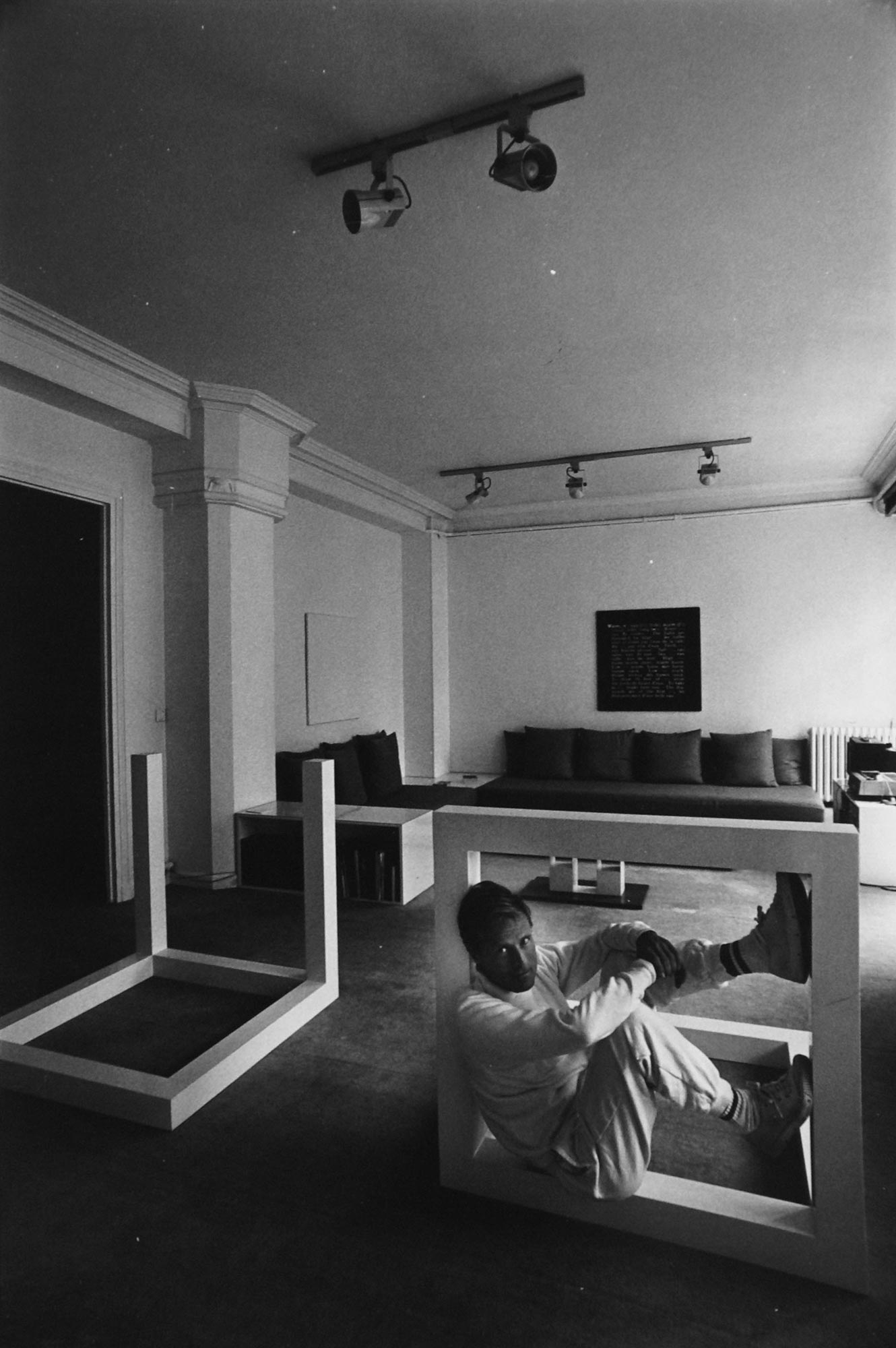

| Ghislain Mollet-Viéville in the rue de Beaubourg apartment in the 1970s |

|

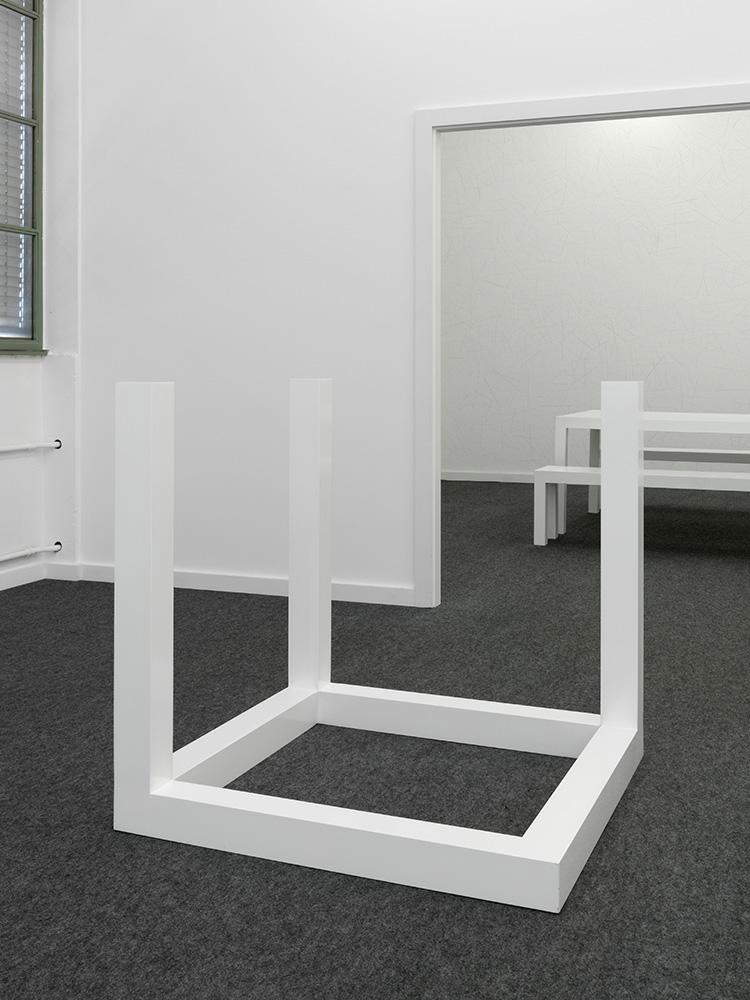

| The Appartement at MAMCO in Geneva, salon. Ph. Credit Annik Wetter |

|

| L’Appartement of the MAMCO in Geneva, salon. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| L’Appartement at MAMCO in Geneva, entrance hall. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

“Compared to the other rooms at MAMCO where different exhibition modes of the same art forms are proposed,” wrote art critic Valérie Mavridorakis, “the Appartement challenges these through their insertion into an everyday private universe. Thus, when its ephemeral inhabitants, that is, visitors, enter this space, they can establish more intimate relationships with the works, at the margins of the experience of the public museum space.” There are basically three criteria, according to Mavridorakis, that guided Ghislain Mollet-Viéville’s choices in the creation of his aesthetic universe: first, the works are in a kind of natural habitat, abandoning all the classical exhibition criteria (space, lighting, bases, frames) giving rise to a freer and more immediate experience. Secondly, the collector based his choices by trying to give birth to a lexicon of elementary and logical forms that completely eschew figurativism and narrative. Lastly, “this art,” Mavridorakis explains, “establishes protocols that are both binding and free: neon can be replaced, wall drawings erased, photographs destroyed and withdrawn, if one follows the artist’s instructions. Thus, the collector becomes in part a maker. Doing and knowing come back into play. And it is up to the collector to shape his works in the context of their existence.”

L’Appartement was set up in accordance with Mollet-Viéville’s ideas, to partially resolve theobvious contradiction generated by the presence of an apartment within a museum (and which is therefore visited by a public that moves according to the dynamics of a museum, even though MAMCO in Geneva is a modern contemporary art museum that is constantly evolving): it is therefore a sober, bare space, almost completely empty as the rue de Beaubourg dwelling was, where what counts above all are ideas, so that the reconstructed apartment in Geneva continues to be that fervent place of exchange, discussion, confrontation and even nonconformity that the real apartment in Paris was. And it is precisely for these reasons that L’Appartement challenges the very idea of a museum, as MAMCO director Lionel Bovier has well explained. “Paradoxically,” says the director, “Appartement brings together a collection in a rather domestic setting within an industrial-type museum.” In fact, MAMCO is housed inside a building that was once a precision mechanics factory, and when it was opened it was decided not to intervene massively on the structure (visitors will notice, for example, that the floors and stairways have not been touched, they are still those of the factory): it is therefore a space that is very consistent with the works displayed in the apartment. The idea of Christian Bernard, director of MAMCO when work began on theAppartement, Bovier explains, “was to introduce doubt within the museum itinerary by reconstructing a collector’s apartment. In other words, it moved a space that many French people, including the collector, had experienced in the 1970s (a remarkable experience, because it was one of the few places in France that defended minimalist art and conceptual art at the same time). And moving this space inside the museum on the one hand reestablishes that experience, but on the other hand it challenges the museum. That is, you are in an industrial-type museum, with its ’white cube’ rooms, and suddenly here are carpets, furniture, and windows that resemble, along with the layout of the rooms, an apartment. From my point of view, this is not an intellectual game: it is a pragmatic and structural experience that is generally perceived by the public as disrupting the visit, changing the state of the visit.”

And this is precisely one of the highlights of theAppartement visit as well as one of its most interesting aspects. “It’s about rules and expectations that are normally erased from the museum discourse. So if we can display the works in the best possible way and at the same time make tangible and visible the fact that they are part of the museum and that there is a narrative behind them and there is a precise context, I think we have done a smart job.” And indeed it is a place that disrupts the normal museum itinerary, because entering it feels like leaving the museum and entering a space of a completely different nature: there is an entrance door, there is furniture, there is a large sofa (where you can also sit), there is a bedroom, there is a television. And the works are displayed according to Mollet-Viéville’s taste: “no paintings, no bases, no frames, no spotlights. The ’paintings’ directly lean against the wall, the sculpture on the floor. The ideal would have been to present works by Barry, LeWitt, Weiner made directly on the walls.” With the result that the works also live in a different way: this art, says Mollet-Viéville, “is perceived as an intellectual art destined only for the aseptic contexts of galleries or museums, but in reality it can also be, in a certain way, art for living.”

|

| The Appartement at MAMCO in Geneva, salon. Ph. Credit Annik Wetter |

|

| L’Appartement at MAMCO in Geneva, salon. Ph. Credit Annik Wetter |

|

| L’Appartement of the MAMCO in Geneva, dining room. Ph. Credit Annik Wetter |

|

| The Appartement of the MAMCO in Geneva, dining room. Ph. Credit Julien Gremaud |

|

| L’Appartement at the MAMCO in Geneva, bedroom. Ph. Credit Annik Wetter |

But what, in detail, are the works that the visitor encounters during his or her tour of theAppartement? One is greeted by a sculpture by Carl Andre (Quincy, Massachusetts, 1935), titled 10 steel row: a kind of metal carpet created with ten simple sheets of industrial steel, which have no other task than to invite the guest inside the house, through a structure to which Andre is very attached because the modules that compose it have no hierarchical relationships of position or volume among themselves, and any module can be replaced without any problem. Opposite, on the walls, is Reflection by Daniel Buren (Boulogne-Billancourt, 1938), strips of painted red canvas applied directly to the corners formed by the walls: a work that, like the fresco of an ancient building, is totally dependent on the place that holds it because each element is in relation to those located on the other corners. We then move on to the living room, the heart of the apartment, where we encounter some of the best-known works: the most striking are certainly the two Incomplete Open Cubes by Sol LeWitt (Hartford, 1928 - New York, 2007), of which there are several examples preserved in various collections around the world. LeWitt had also stated that “the most interesting feature of these cubes lies in the fact that they are relatively uninteresting works. Compared to any other three-dimensional form, the cube lacks any aggressive force, implies absence of movement, and because it is a standard form no skill is required on the part of the observer. It is immediately understood that a cube represents a cube, a geometric figure in itself uncontestable.” Yet even a cube can instead become an interesting object: first, because its structure can be broken down (so much so that, with the help of some mathematicians, LeWitt found more than a hundred possible variations). And then because the incomplete cube suggests to our imaginative capacity to recompose the complete structure. And in the apartment, moreover, the cubes are arranged so that they are in line with the coffee table in the living room, in perfect continuity of form.

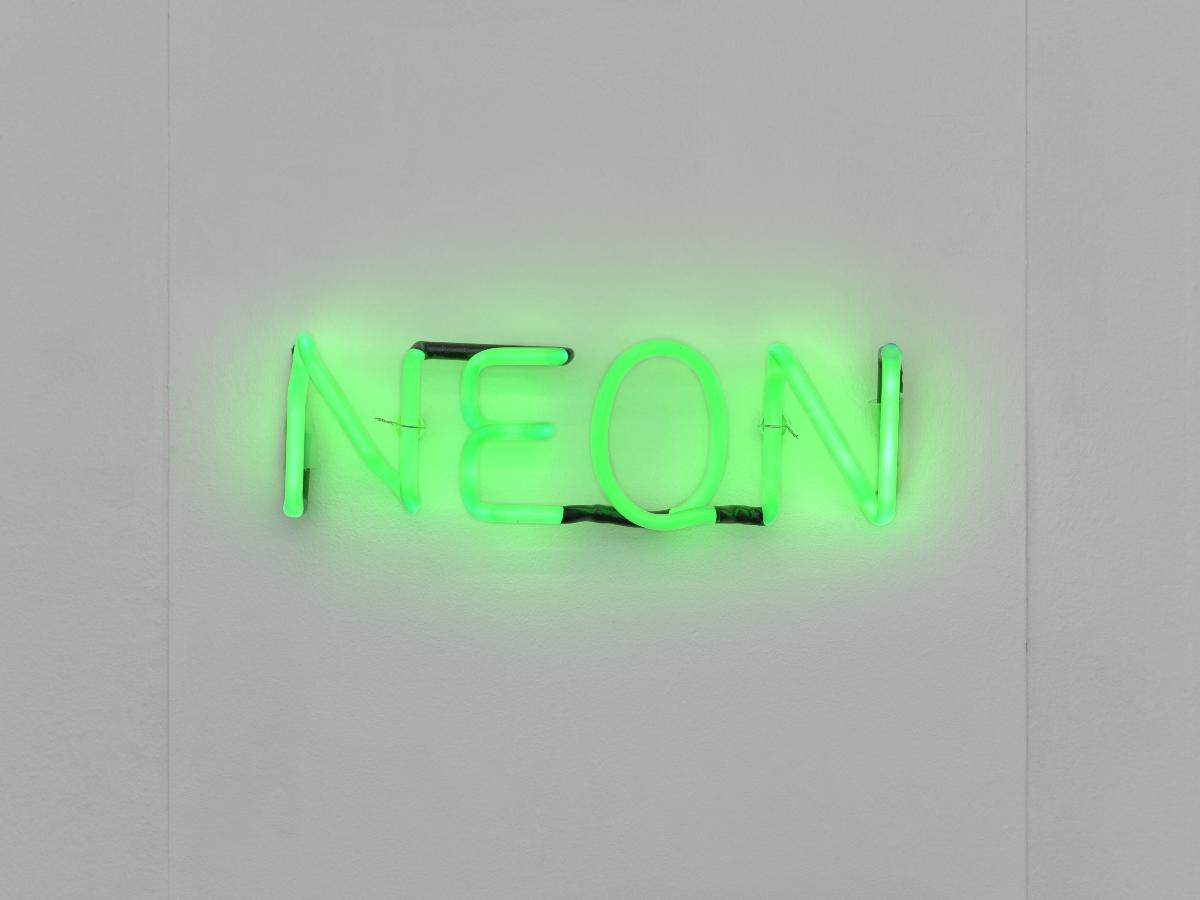

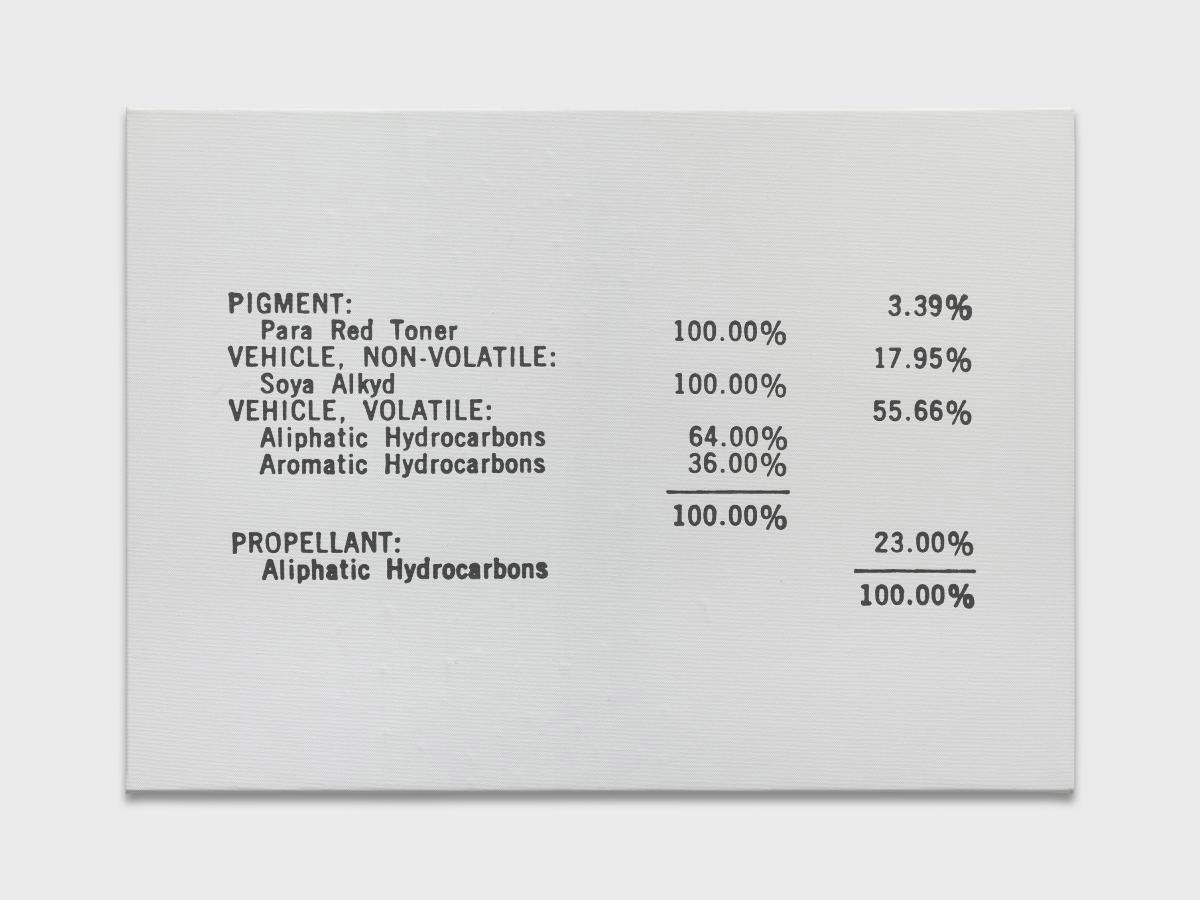

From geometric form we move on to words: on the windows we find a conceptual work by Lawrence Weiner (New York, 1942), In and out - Out and in - And in and out - And out and in, which shows this sequence of words on the glass. It is one of the American artist’s best-known works, not least because underlying it is one of the foundational elements of conceptual art: “what makes a work of art is more important than how it was made,” the artist says. And in this case, the dimension the work focuses on is the relationship between outside and inside, so much so that Mollet-Viéville decided to install it directly on the window (with the word “In” pasted on the inside glass and “Out” on the outside glass), which at least since Romanticism has been a symbol of all the tensions that cross the threshold between inside and outside. The salon then hosts Neon by Joseph Kosuth (Toledo, Ohio, 1945), one of the U.S. artist’s classic conceptual works that reflect on the signifier and the signified: however, whereas in most cases they do so in three separate moments (the real object, its reproduction, and the word that defines it), in this case the object is all together, namely neon as object, as verbal definition, and as light emanating from it and thus reflecting a real-time reproduction of the work on the wall. There are also paintings: on the wall leading toward the dining room we find 100% Abstract by Englishman Mel Ramsden (Ilkeston, 1944), an abstract work in the true sense of the word since the artist, instead of depicting a scene or an object, fills the canvas with a verbal description of the materials used to create the work.

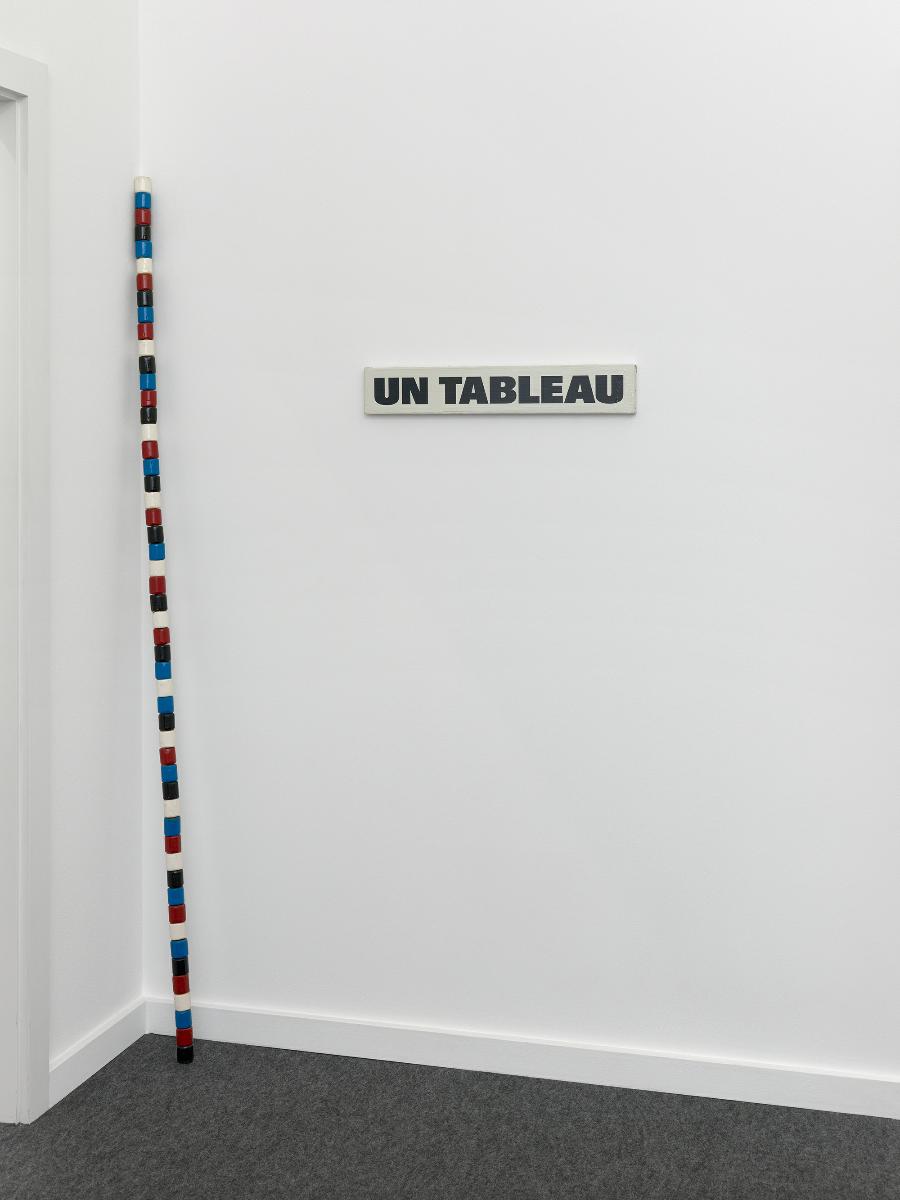

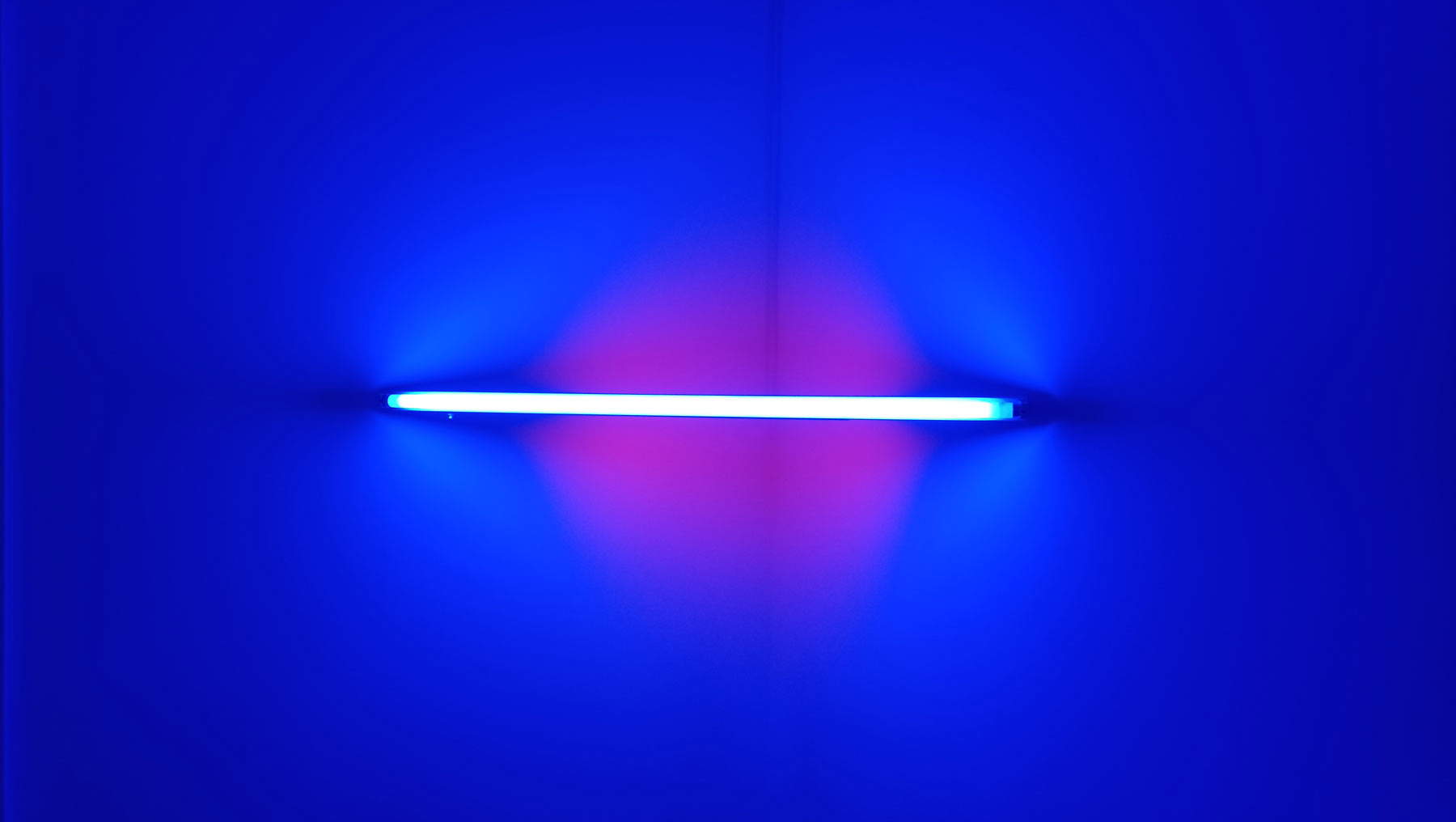

We then move on to the dining room, where we find one of André Cadere’s (Warsaw, 1934 - Paris, 1978) color bars, the works that the artist used to leave at the openings of his colleagues’ exhibitions in order to disturb and subvert the cultural milieu of 1970s Paris, and then another painting by Ramsden, Guaranteed painting (a kind of certificate that instead of guaranteeing the work’s authenticity ... guarantees its measurements) and a monochromatic work by John McCracken (Berkeley, 1934 - New York, 2011), a large rectangle of green polyester resin, an object somewhere between painting and sculpture that studies the relationships of form and color to the space that accommodates them. After visiting the office space, one returns to the hall from where one then passes into the antechamber: here, the wall is decorated with another work by Weiner(From white to red - From wood to stone - From sea to sea), and with a neon work by Dan Flavin (New York, 1933 - 1996), entitled Blue and red fluorescent light, where the surface of the work is also determined by the light that is emitted by the neon, thus causing the work to be delimited by the space that houses it, and that the space in turn is invaded (and thus transformed) by the artwork, with the goal of abolishing any barrier between the environment and the object that the environment exhibits (so that one no longer has a work, but rather a “situation” or, as Mollet-Viéville would put it, “a place of perceptual experiences related to the displacement of the viewer”). In addition, unlike traditional artworks, Flavin’s, being partly composed of light, removes the concept of contact with the work, effectively introducing its dematerialization.

We come, therefore, finally to the bedroom. On the wall we find hanging, meanwhile, a kind of shelf, the work of Donald Judd (Excelsior Springs, Missouri, 1928 - Manhattan, 1994), entitled Stainless steel, or “stainless steel,” the material of which it is composed: it is one of the typical three-dimensional geometric volumes, in elementary forms and made of industrial materials, that populate Judd’s art and constitute his answer to the age-old problems of art history (“three dimensions,” the artist wrote in 1967, “are a real space. This solves the problems of illusionism and literal space, the space that surrounds or is contained in signs and colors: which means that we have got rid of the most relevant and most objectionable relics of all European art.”). On the adjoining wall, appears one of the so-called date paintings by Japanese artist On Kawara (Kariya, 1932 - New York, 2014), works that deal with time through the reproduction, on canvas, of the very date on which the painting is produced (and in which therefore time is fixed), a mode through which the painter intends to stop the present and deliver it to the future. Finally, on the bedside table, one will notice the presence of a polished steel bar: this is High energy bar by Walter De Maria (Albany, 1935 - Los Angeles, 2013).

|

| Carl Andre, 10 Steel Row (1967; ten steel modules, 1 x 300 x 60 cm; Geneva, MAMCO) |

|

| Daniel Buren, Reflection, une peinture en 5 parties pour 2 murs (September 1980; red and white canvas strips, dimensions varying according to the wall, here 183.5 x 140 cm; Geneva, MAMCO) |

|

| Sol LeWitt, Incomplete Open Cube. Seven Part Variation No. 1 (7-1) (1973-1974; lacquered aluminum, 105 x 105 x 105 cm; Geneva, MAMCO) |

|

| Joseph Kosuth, Neon (ca. 1965; neon, 10.5 x 35.5 x 4.5 cm; Geneva, MAMCO) |

|

| Mel Ramsden, 100% Abstract (October 1968; enlargement on canvas, 48 x 64 cm; Geneva, MAMCO) |

|

| André Cadere, Barre de bois rond (Jan. 25, 1976; 52 round wood segments lacquered black, red, blue, and white, 208 x 4 cm; Geneva, MAMCO) |

|

| John McCracken, Spiffy Move (1967; polyester resin on fiberglass and wood, 264.5 x 46 x 8 cm; Geneva, MAMCO) |

|

| Dan Flavin, Untitled (Blue and Red Fluorescent Light) (ca. 1970; neon, 122.5 x 61.5 cm; Geneva, MAMCO) |

|

| Donald Judd, Stainless Steel (1965; stainless steel, 15.2 x 68.2 x 61 cm; Geneva, MAMCO) |

|

| Walter De Maria, High Energy Bar No. 78 (1966; stainless steel, 3.7 x 35.7 x 3.7 cm; Geneva, MAMCO) |

But for what reasons did Mollet-Viéville end up transporting his apartment from Paris to Geneva by deciding to reconstruct it in a museum? It is the “agent d’art” himself who recalled the circumstances under which he began this adventure, in the interview he gave to Lionel Bovier and Thierry Davila for the publication L’Appartement, currently MAMCO’s most monograph on space, published in February 2020. “It was 1993,” recalls Mollet-Viéville, “and Christian Bernard came to me because I had to lend him some works from my collection. He was preparing for the opening of his new museum, MAMCO, and he wanted to get loans from collectors in order to create a targeted exhibition. I responded to his request by telling him that he could choose from my collection whatever he wanted because, in my new apartment in the Bastille, I would not put any works, in order to show the aesthetics of an empty space, witness to an art no longer tied to the conventional nature of its objects. Christian’s reaction was immediate. He wanted to borrow all the works he had seen in my rue Beaubourg apartment and, logically, he told me that the ideal would be to reconstruct the space in which I lived in order to present my collection as a global work. Coincidentally, on the third floor of the museum, there are three large glazed windows that resemble the windows of my rue Beaubourg apartment, and it was from them that the reconstruction of the walls and furniture was designed and made.”

100% faithful reconstruction was not possible, but the degree of approximation is very high: Mollet-Viéville said that his friends who had been to his home, visiting MAMCO for the first time were amazed by the degree of verisimilitude of the reconstruction. Indeed, the configuration of the spaces was identical to that of the Beaubourg apartment, the furniture (which Mollet-Viéville sold in 1992) was reproduced in shapes equal to the originals, the arrangement of objects in the apartment followed, of course, that which the collector had imagined for his home. And in the end, L’Appartement ended up becoming itself a work of conceptual art, where the idea is more important than the outward appearance, but where the latter concurs to express the ideas of its creator: “an ensemble consistent with my lifestyle and coherent with the minimalist and conceptual artworks in my collection.” And that apartment, which in the 1970s hosted the artists and personalities of the up-to-date Parisian cultural milieu of the time, is now available to all who pass through Geneva.

Essential Bibliography

- Lionel Bovier, Thierry Davila, Patricia Falguières, Ghislain Mollet-Viéville, L’APpartement, Les Presses du Réel, 2020

- Pierre-Nicolas Ledoux, Ghislain Mollet-Viéville, Alain Pacadis, Jacques Serrano, GMV. Is there any Ghislain Mollet-Viéville?, Les Presses du Réel, 2011

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati

Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da

Federico Giannini e

Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato

Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009.

Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamo

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.