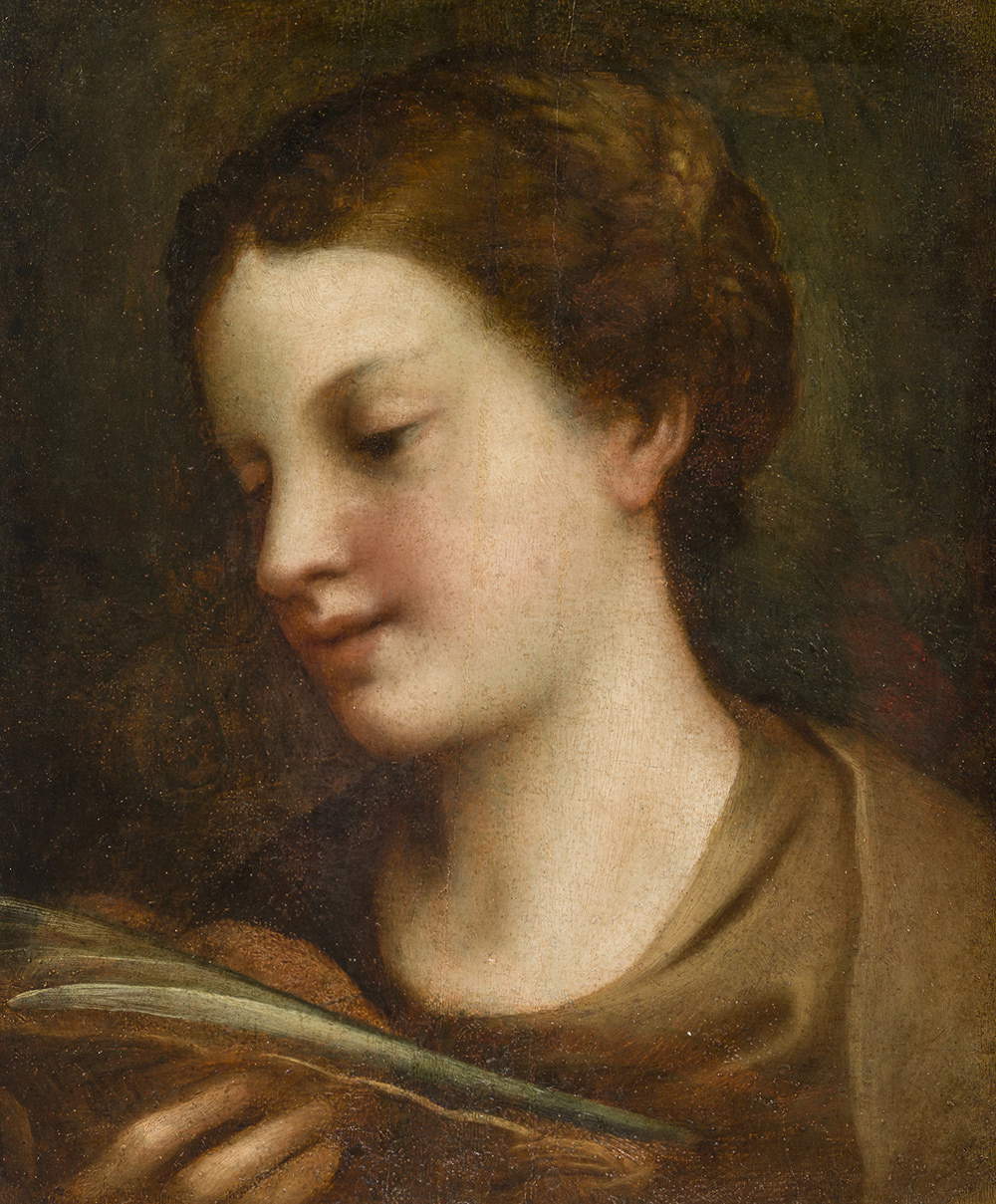

Correggio ’s Saint Agatha (Antonio Allegri, Correggio, c. 1489 - 1534) is a girl with the sweetest features, thoughtful, dense with humanity: little more than a child, her cheeks slightly flushed, and her brown hair pulled back, with the faint light lingering on a few locks. A maiden who, strong in her faith and thus in her convictions, feels no pain in looking at her severed breast, on the silver saucer she holds in her hands, her graceful, tapering fingers bringing it close to her eyes. No movement of fear, nor any visible sign of suffering: on the contrary, the gaze is calm and serene, since the very young martyr knows well what reward awaits her. A reward that is already heralded by the palm tree we see resting on the saucer: associated with all Christian martyrs, the palm tree, according to an ancient Eastern belief, was thought to die once its seeds were scattered. A sacrifice, in short: the same to which the Christian martyr offers himself to bear witness to his faith (and “witness” is the meaning of the word martys in Greek). But in ancient times palms were also given as prizes to the winners of athletic competitions: and in this sense, martyrs are winners because, St. Maximus of Turin argued in his Sermons, “to have come to the grace of the Gospel is to have won.”

According to hagiographic tradition, St. Agatha is said to have suffered her martyrdom when she was just sixteen years old: born in 235 in Catania to a noble family of the Christian faith, at the age of fifteen she was said to have devoted herself totally to God, but at the same time received the morbid attentions of the city’s proconsul, Quinziano. In order to have her, the proconsul would enforce against her theedict of Emperor Decius ordering all Roman citizens to publicly offer a sacrifice to the pagan gods: those who made the sacrifices received a certificate, and those who refused were arrested and sentenced to death for impiety. Having St. Agatha arrested and taken to the Praetorian Palace, Quintianus allegedly tried to seduce the maiden, but obtained a flat refusal in return: enraged, the proconsul allegedly ordered the young virgin to be tortured, and above all to have her breasts torn off with a pair of large pincers. Miraculously healed by St. Peter appearing to her during the night of the torture, she would later be condemned to be burned on hot coals. Hagiographies report that, while Agatha was already enveloped in flames, a violent earthquake shook Catania, causing the Praetorian Palace to collapse and saving the young woman: the people of Catania, struck by the affair, would protest against the torture inflicted on poor Agatha. Quinziano would therefore decide to imprison her, but the girl, in agony, would die a few hours after her imprisonment. Her flammarium, the red veil that identified her as a consecrated virgin, would remain intact, and was thus venerated as a relic by the Catanese. St. Agatha is today the patron saint of Catania (a very well attended procession is held in her honor every year in the Sicilian city), as well as one of the three patron saints of the Republic of San Marino, and by virtue of the kind of martyrdom she suffered she is also the patron saint of women suffering from breast diseases: but in general her cult is widespread, since St. Agatha, because of her story, is one of the Christian heroines most closely associated with the female world.

And Correggio’s St. Agatha is, indeed, a young woman who shows the age of the saint at the time of her martyrdom, and she is beautiful, of a beauty that exudes love, lively participation, empathy with the subject and with the model, so much so that, shortly after her discovery, Dario Fo speculated that St. Agatha might be a portrait of the painter’s young (and gorgeous, at least according to tradition) wife, Jeronima (or Girolama) Merlini. Born in 1503, and therefore some fifteen years younger than her husband, Jeronima was the daughter of a man-at-arms named Bartolomeo, who died in the same 1503 while fighting for the marquis of Mantua, Francesco II Gonzaga. She married Antonio Allegri in 1519 and bore him four children: Pomponio, who followed in his father’s footsteps by also becoming a painter, Francesca Letizia, Caterina Lucrezia and Anna Geria. He disappeared prematurely, only 26 years old, in 1529.

|

| Antonio Allegri known as Correggio, SantAgata (1525-1528; oil on panel, 29 x 34 cm; private collection) |

|

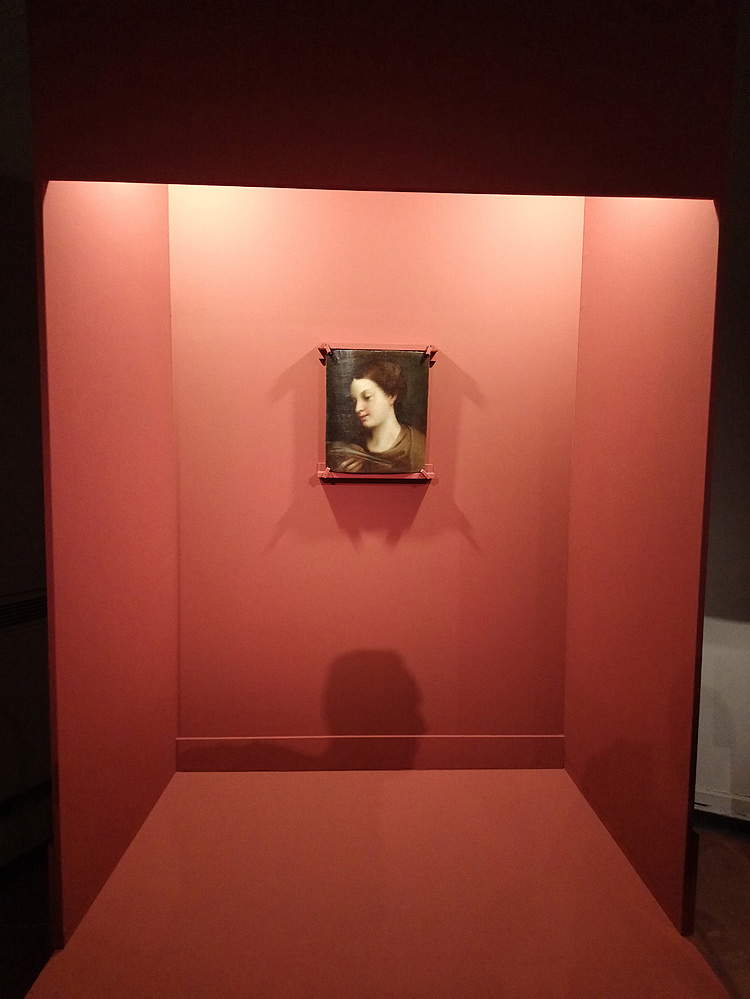

| Setting up of the Sant’Agata on the occasion of the exhibition Il Correggio ritrovato a Correggio |

Dario Fo’s hypothesis is admittedly romantic and certainly spurs the fantasies of the relative, but of course it is completely unsupported and difficult, if not impossible, to prove. It must be said, however, that the great writer and playwright (who in the last years of his career, as is well known, also gave himself up to art-historical popularization) was not the only one to believe that Correggio’s wife was also a model for his paintings, although it must be stressed that similar hypotheses are indeed fascinating, but at the moment they are without foundation and do not represent a relevant interest for art-historical studies. They are, after all, suppositions that pertain more to the world of letters than to that of scientific research: in addition to Fo, for example, an asserter of the hypothesis of Girolama as Antonio’s model was one of the greatest French writers of the late 19th century, �?douard Schuré (Strasbourg, 1841 - Paris, 1929), who in 1900 published a biographical essay on the Emilian artist, in which a chapter was included, entitled Le Corrège et le génie de l’amour, in which he supported the hypothesis on the basis that, after his marriage in 1519, Correggio would intensify his production of Madonnas, and they all turned out to have more or less the same features and connotations. This was enough for Schuré to consider it likely that there was only one model, and what is more, one who was particularly familiar to him. Even, at the beginning of the 19th century, the relationship between Correggio and his bride was the subject of a tragedy, entitled Correggio, and written by the Danish playwright Adam Gottlob Oehlenschläger (Frederiksberg, 1779 - Copenhagen, 1850), inspired by a visit to the home of his friend Bertel Thorvaldsen (Copenhagen, 1770 - 1844), the great sculptor and rival of Canova. In the tragedy, written in 1809, Oehlenschläger followed Vasari’s account of the death of the painter, who is said to have died in 1534 from severe sunstroke while on his way from Parma to Correggio with a sack of coins received as payment for a work: in the drama, his wife (who is called “Maria” by Oehlenschläger) nevertheless manages to reach him on the way and summons a friar to give the artist last rites. The ending of Oehlenschläger’s tragedy would, moreover, inspire a Danish painter of the time, Albert Küchler (Copenhagen, 1802 - Rome, 1886), who in 1834 painted a work depicting precisely Correggio’s death.

|

| Adam Oehlenschläger’s Correggio |

|

| Albert Küchler, The Death of Correggio (1834; oil on canvas, 83.7 x 74.5 cm; Copenhagen, Thorvaldsens Museum) |

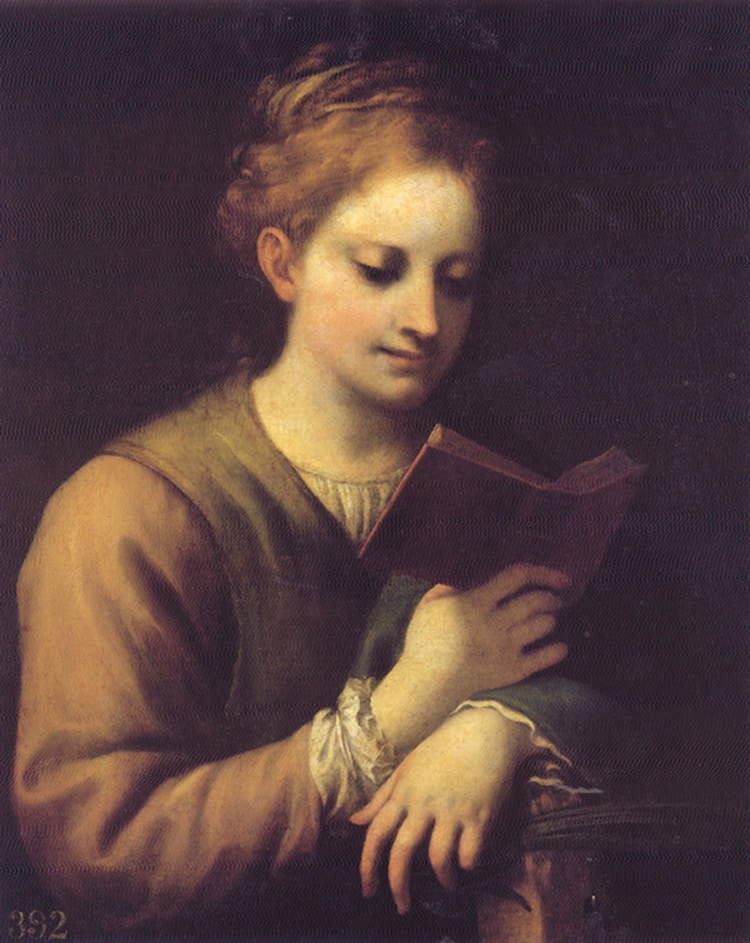

Beyond the theatrical and literary suggestions, from stylistic comparisons it is nevertheless conceivable that the Saint Agatha can be placed in a period between 1525 and 1530: Giuseppe Adani, a Correggio scholar who is firmly convinced of the attribution of the saint to the hand of the Emilian painter, is convinced of this, on the dual basis of comparisons with the artist’s other works, and the results of technical analysis. “Allegriana’s execution,” Adani wrote, "is placed in the second lustre of the 1620s, when the painter, at the height of his own brilliant maturity, put his hand to some subjects of vibrant participation such as theAdoration of the Uffizi, the Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine of the Louvre, the St. Catherine of Hampton Court, and other female visions in which we find the physiognomic characters identical to those of St. Agatha. It might be said that the small panel [...] was, as a first proof, the model of a face dearly approached by the master and then happily transposed into important works." In fact, we do not know for whom the artist painted the work, nor under what circumstances it was done, and obviously we do not know with certainty the year of execution: given the format, however, it is possible to think that it was a study for a larger work.

As for the analysis of the technicians, it must be premised that some of the most relevant data emerged in 2004, in the aftermath of the restoration of the tablet carried out in Milan by Pinin Brambilla Barcilon, the famous restorer who has dealt with masterpieces such as Giotto ’s frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, those of Masolino da Panicale in Castiglione Olona, but who is most famous worldwide for her long restoration of theLast Supper that Leonardo da Vinci left in the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in the Lombard capital: a challenging intervention that lasted from 1978 to 1999. Brambilla Barcilon’s analysis is one of the most interesting and complete on the St. Agatha: the restorer noted how the painting had suffered due to an ancient intervention on the support, carried out to consolidate it but resulting in the accentuation of two vertical cracks, but also how “the tonal variations and chiaroscuro are obtained through a superimposition of thin transparent veils according to traditional painting techniques,” and that “the face and hair of the woman are characterized by an extremely meticulous and refined execution.” Meanwhile, the 2004 restoration focused on the support: its thickness was regularized and action was taken to allow the wood to move with respect to changes in humidity. On the surface, on the other hand, a thorough cleaning was carried out: the yellowed varnish was removed, and so were the underlying patina and atmospheric particulates. Finally, the restorer proceeded with some slight additions and a thin varnish in order to give greater firmness and luster to the colors.

On the same occasion, an X-ray was performed on the painting that revealed the presence of some figures that were part of a Crucifixion. Further analysis was conducted between 2016 and 2017 in the laboratories of the Vatican Museums: on this occasion, restorer Claudio Rossi de Gasperis analyzed the pigments, comparing them with those of four other works by Correggio, and was also able to confirm the autography on a technical basis. “What has been observed and described,” Rossi de Gasperis stated in the results of the analysis, a nine-page report entitled Indagini sulle preparazioni colorate del Correggio, "can only validate the hypothesis of the attribution of Allegri’s painting of Sant’Agata. The fact that the work was made with the same colored preparations, found in the four Correggio paintings in the comparison, analyzed here, confirms this. Moreover, such preparations indicate a deep and sophisticated study of the different effects transmitted to the chromatic surface, so we can deduce that Allegri achieved, with careful care, those marvelous atmospheres and complexions that so characterize him. It can also be added that never has a copyist, however good, been able to grasp such refined devices, nor have that freedom and confidence necessary to spread the color and, through the different thicknesses of his brushstrokes, to create those particular chiaroscuro accents that belong only to a great artist." These conclusions were later confirmed by further analysis, carried out in 2017 by engineer Claudio Falcucci’s M.I.D.A. studio.

|

| Antonio Allegri known as Correggio, Madonna in Adoration of the Child (1525-1526; oil on canvas, 82 x 68.5 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Antonio Allegri known as Correggio, Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine (1526-1527; oil on canvas, 105 x 102 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

|

| Antonio Allegri known as Correggio, Saint Catherine Reading (c. 1530; oil on canvas, 64.5 x 52.5 cm; Hampton Court, The Royal Collection) |

The existence of Correggio’s Saint Agatha, however, is not a recent discovery. The first mention of a work by Correggio depicting the Catanese saint dates back to 1866 and is a passage in a work of travel literature: An Artistic Excursion to Sinigaglia by Alfredo Margutti, published in Florence in 1866, mentions it as a work by Correggio and advises the reader to go to admire it at the home of the widow of the surgeon Angelo Zotti (Imola, 1833 - Senigallia, 1884), a physician so skilled that, in Senigallia, his figure literally became proverbial. Zotti was Senigallia’s deputy surgeon from 1866, a role he held until his death in 1884: records report that one of his operations saved the life of an English gentleman who was staying in the Marche town, and the patient, to thank Zotti, allegedly gave him the St. Agatha. It is not known, however, how the work came to England: it was probably bought on the Italian antiquarian market, perhaps in the 18th century, by an English traveler, but the painting’s previous history is currently unknown (“a prospecting on the records of English private collections, very numerous in the 18th and 19th centuries,” wrote Giuseppe Adani, “could shed light” on the subject). Through some hereditary passages, the work arrived, during the twentieth century, in the collection of two sisters from the Marche region with residences in Rome and Fano (and it was in their collection that Dario Fo saw the painting, pointing it out to Pinin Brambilla: the restorer, in turn, published it in the volume Correggio who painted hanging in the sky published by Panini in 2010).

The most recent chapters in the history of the Sant’Agata are the two exhibitions that, in 2018, brought it to the public’s attention. The first was held right in Senigallia (by virtue of the aforementioned connection between the city and the work), at Palazzetto Baviera, from March 15 to September 2. The second, on the other hand, brought the saint “back home”: it was the exhibition Il Correggio ritrovato, held at the Museo Civico "Il Correggio,“ in Antonio Allegri’s hometown, from September 22, 2018 to March 17, 2019. The public thus had the opportunity to take a close look at that ”poetry of spiritual enchantment made painting,“ a ”pearl of the soul made visible by Antonio da Correggio’s sail brush" (thus Giuseppe Adani) that the association of the Friends of Correggio has finally brought to the Emilian town.

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.