The birth of New York’s MoMA, considered one of the most important museums of modern art in the world and now located on Manhattan’s 53rd Street, was due to the extraordinary vision and great insight of threelocal high society women: Abigail “Abby” Aldrich Rockefeller (Providence, 1874 - New York, 1948), Lillie Plummer Bliss (Boston, 1864 - New York, 1931) and Mary Quinn Sullivan (Indianapolis, 1877 - New York, 1939). The idea came primarily to Abby Rockefeller, wife of U.S. businessman John Davison Rockefeller Jr, heir to the wealthy oilman of the same name: “I began to think of women I knew in New York City who had a deep interest in beauty and who bought paintings; women who would be willing and who had enough faith to help create a museum of modern art. Mrs. Lillie Bliss and Mrs. Mary Quinn Sullivan were perfect in this regard; I asked them to have lunch with me and expounded the matter to them,” Abby recounted in 1936, recalling how this ambitious project had begun. He invited them to lunch one day in 1928 and then made them part of his idea.

Indeed, the deaths of collector and patron John Quinn in 1924, who was part of the group that in 1913 had organized theArmory Show, the first major exhibition of European and American modern art in the United States, and of Arthur Bowen Davies in 1928, a painter also among the organizers of the Armory Show as well as an adviser to Lillie P. Bliss, and the consequent dispersal of their large and important collections of modern art, had made it necessary to create a museum for modern art in New York. Indeed, in MoMA’s first brochure dating back to 1929, it had been specified that only New York, among the great capitals of the world, did not possess a public museum where the artworks of the founders and masters of the modern schools could be kept and made visible to the public. That the American metropolis did not have a museum fit for this purpose had been called a "strange anomaly.“ Museums in the cities of Oslo, Frankfurt, Utrecht, Lyon, Prague, Cleveland, Chicago, Buffalo, Detroit, Providence, Worcester and many others ”offered students, enthusiasts and the interested public many permanent exhibitions of modern art.“ And in these museums it was ”possible to gain some insight into the progressive phases of European painting and sculpture over the past fifty years,“ and more importantly, those exhibitions were the modern public collections of the world’s largest cities, such as London, Paris, Berlin, Munich, Moscow, Tokyo, and Amsterdam. ”This is why,“ the brochure says, ”New York should take a cue from these, because they solved the problem that New York is facing. A delicate and complex problem."

After that lunch in 1928, Abby Rockefeller, Lillie P. Bliss and Mary Quinn Sullivan then began to think about an institution in which to bring together and exhibit their modern art collections and asked Anson Conger Goodyear, collector and former managing director of the Albright Gallery in Buffalo to be the first president of that museum, while for the first board of directors they called in patron Josephine Boardman Crane, journalist and critic of American art and theater Frank Crowninshield, and businessman Paul Joseph Sachs, the latter of whom became famous for starting as early as in 1922 one of the first and innovative courses in the United States on museum management, both in the curatorial and financial aspects. It was Sachs, director and curator of the prints and drawings section of the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, who was in charge of the curatorial search, and it was he who also suggested the name of Alfred Hamilton Barr Jr. as director of the museum, a young student of his who taught the only course in modern art in the country.

Nelson Rockefeller, Abby’s son, later stated: "The combination was perfect. The three women, namely my mother, Lillie Bliss and Mary Sullivan, had the resources, tact and knowledge of art needed." They were nicknamed "the Ladies," "the daring Ladies," and "the adamantine Ladies." Abby Aldrich Rockefeller had a particular fondness for art on paper by living Americans and collected several works between 1925 and 1935; she was also a patron, so she directly supported artists through commissions, acquisitions, and financial aid. She is credited with many donations to the Museum of Modern Art, including paintings, prints, sculpture and funds to purchase works from 1935 to 1948, the year of her death, at which time Director Barr wrote to the founder’s son Nelson Rockefeller, “She was the heart of the Museum and its center of gravity.”

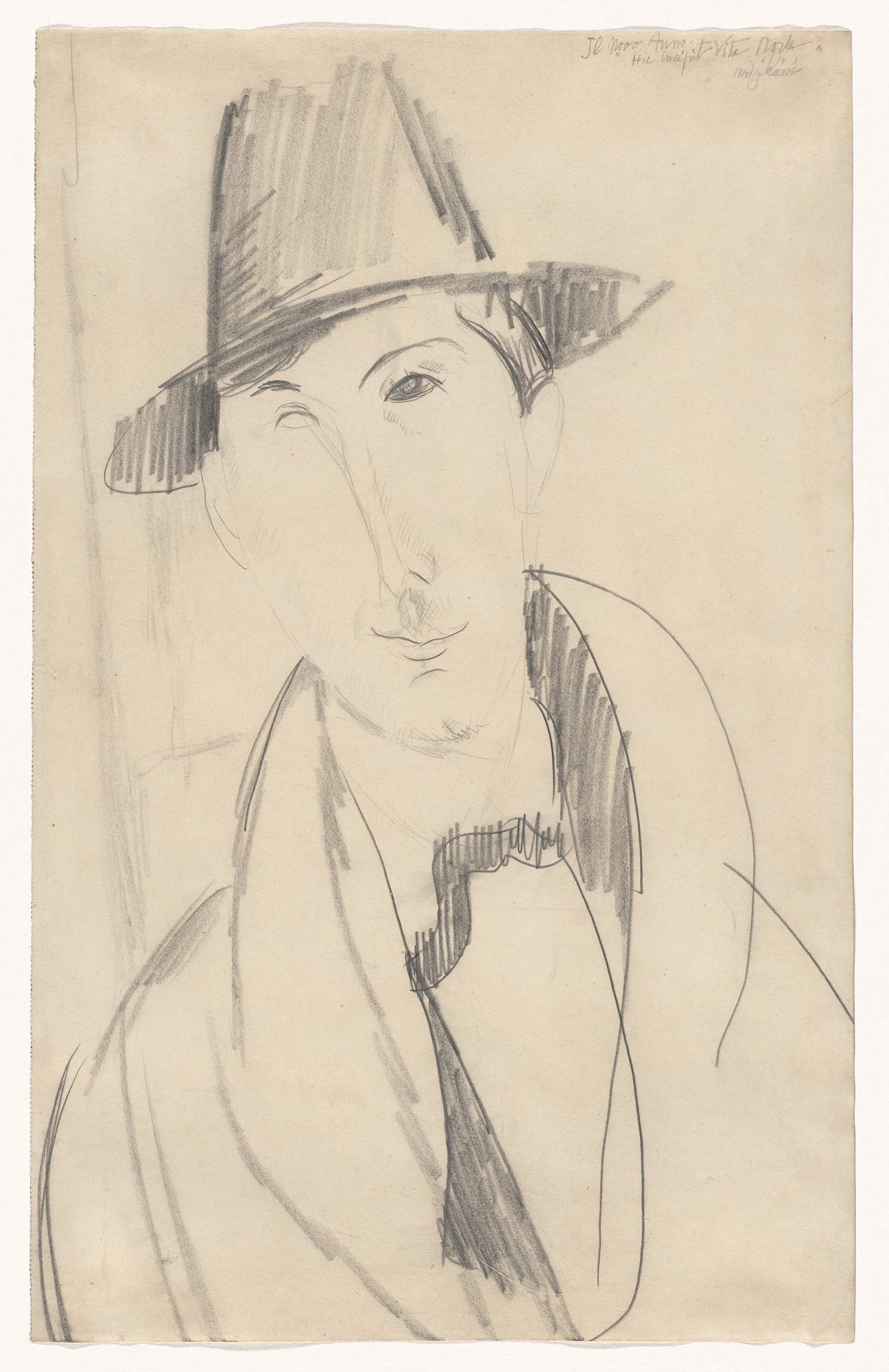

Lillie P. Bliss had financially supported the 1913 Armory Show and also purchased works in the exhibition; she had also bought works from John Quinn’s collection at auction and acquired works from Davies’ collection when he died. Bliss’s collection thus included at her passing works by celebrated artists such as Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani, Pablo Picasso, Odilon Redon, Georges Seurat, Henri Rousseau, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and most of these works flowed into MoMA’s collection-a substantial body of work that proved to be a great gift to the museum venue. Mary Quinn Sullivan, on the other hand, was anart teacher, wife of a well-known lawyer as well as collector of art and rare books, Cornelius Sullivan. She owned important paintings by Paul Cézanne, Amedeo Modigliani, Pablo Picasso, and Henri de Toulouse Lautrec in her collection. Of the three founders, the latter was the one who was most knowledgeable about art education, thus about teaching the visual arts, an element that characterized the museum institution from the start. However, in 1933, Sullivan abandoned the position of trustee as she opened a gallery of her own.

Less than a year passed since that luncheon, and on November 7, 1929, a little more than a week after the Wall Street crash, the Museum of Modern Art opened with an exhibition devoted to the modern masters in the twelfth-floor spaces of an office building, the Heckscher Building, at 730 Fifth Avenue in New York City: it featured works by Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Seurat, mainstays for early twentieth-century painting. The museum would later change locations several times, until it moved, in 1939, to 53rd Street, its current home.

According to Barr’s idea, the museum’s collection was to be like "a fish moving through time, its snout is the ever-changing present, its tail is the ever-elusive past of fifty to one hundred years ago." The institution had no money (in fact, Abby’s wealthy husband refused to give funding because he opposed his wife’s project and also disliked modern art), so the first collection was established through donations: it consisted of eight prints, mostly of German expressionism, and one drawing, donated in 1929 by Sachs. The lack of and difficulty in finding funding also caused the museum to move to many locations (in the first ten years three different locations), but eventually the current location was built on land donated by Rockefeller himself, who later became among the major donors. The most significant donation after the first, however, was due to a bequest in 1934 from co-founder Lillie P. Bliss who had died in 1931, while thanks to an anonymous donation in 1930 the first painting by an American artist, House by the Railroad by Edward Hopper, entered the museum collection.

At the museum’s founding in 1929, the seven trustees signed a document expressing their intentions, first among them to organize a series of exhibitions over the next two years that would constitute as comprehensive a representation as possible of the great modern masters, American and European, from Cézanne to the present, but especially of living artists, with occasional tributes to the masters of the nineteenth century. Second, to obtain through the cooperation of artists, owners and dealers a number of first-rate paintings, sculptures, drawings and lithographs for exhibitions. Finally, to create a permanent public museum in the city that could acquire, over time (either through donations or purchases), the best works of modern art.

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, Lillie P. Bliss, and Mary Quinn Sullivan knew how to believe in modern art that had been under-appreciated and under-understood, and certainly the Armory Show of 1913 was a great impetus for understanding the need to have a public museum in New York City as well that would bring together recent artistic innovations, including the American output of living artists. They were passionate about an art that few loved, but through their skillful intelligence, support for young artists, and personal experience they carried out their project and succeeded in bringing to life what is now one of the world’s most important museums, selecting artists’ works with taste, courage, and with a dash of foresight.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.