In the early sixteenth century an Umbrian noblewoman, Atalanta Baglioni, found herself involved as much in a bloody episode that destroyed her family, profoundly marking the history of the city of Perugia, as in the artistic affair that contributed decisively to the affirmation of the young Raffaello Sanzio (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520).

In July 1500, in fact, Atalanta’s son Federico Baglioni, called “Grifonetto” after the name of his father Grifone who died when he was a child, took part in a conspiracy against some members of his own family, later paying for this choice with his life.

At the time, Grifonetto’s great-uncles on his paternal side, brothers Guido and Rodolfo Baglioni, were at the head of Perugia’s city oligarchy, and exercised, de facto if not de jure, control over political and civic life. According to the sixteenth-century Chronicle of the City of Perugia 1492-1503, it was against the two men and their sons that Carlo Baglioni known as “Bargiglia,” brother of Guido and Rodolfo, with the support of the Duke of Camerino, Giulio Cesare Varano, hatched a plot, which was joined by other members of his household including the very young Grifonetto. However, one of Guido’s sons, Giampaolo, managed to escape the onslaught of the conspirators, left the city and returned the next day, with numerous men in his retinue, to take his revenge. Thus it was that, in his early twenties, Grifonetto died.

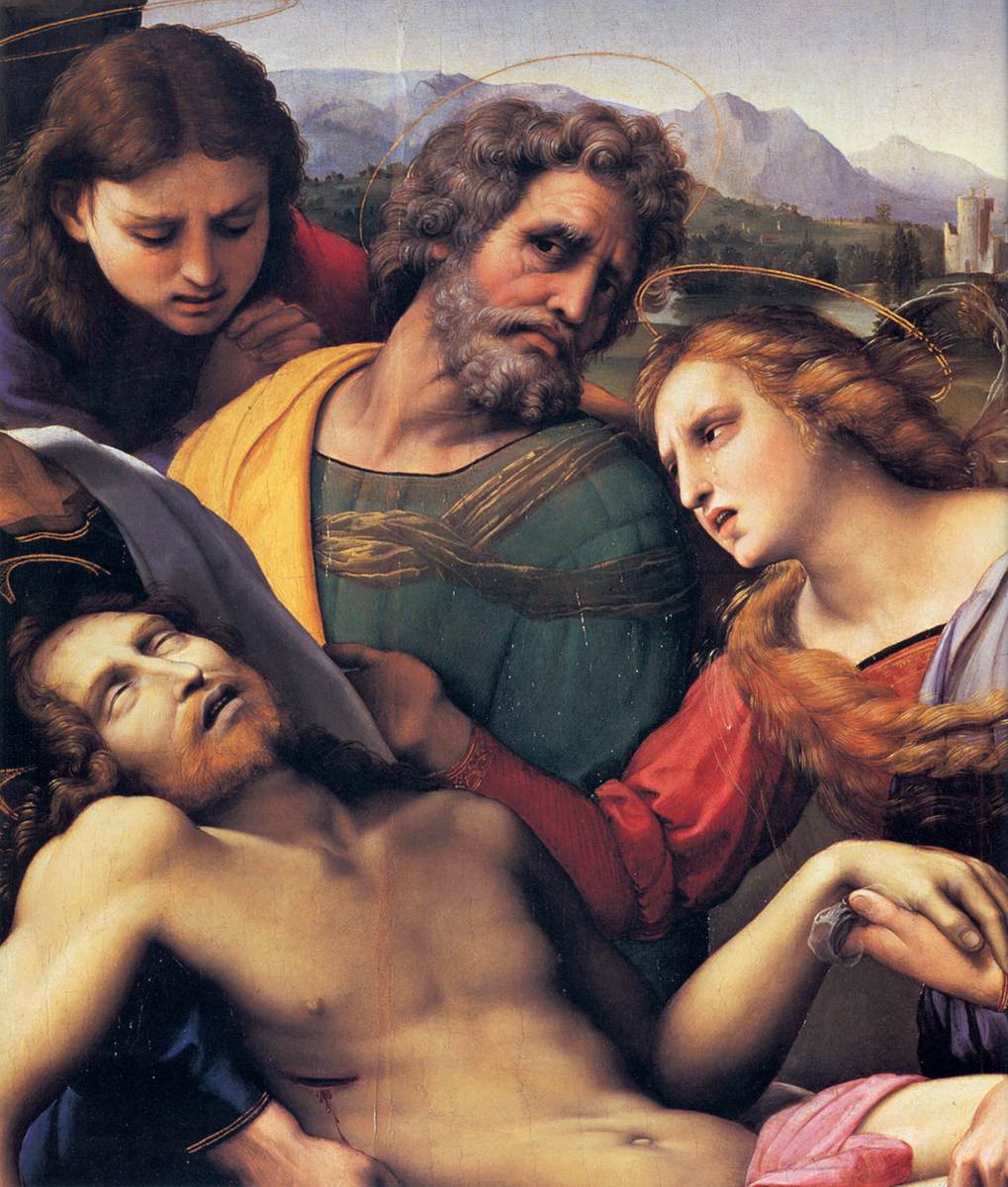

Vasari in his Life of Raphael writes that, years after these bloody events, Atalanta commissioned the painter to paint a panel depicting “a dead Christ brought to bury.” This, then, is the Transport of Christ to the Tomb, better known as the Baglioni Deposition or Baglioni Altarpiece, which is now housed in the Borghese Gallery in Rome.

One of the most important confirmations about the identity of the person from whom the commission came is a letter written by the Marche painter while he was in Florence (on the front of a sheet on which is drawn a Holy Family now in the Wicar Museum in Lille) and sent to his pupil and friend Domenico Alfani, who was in Perugia; in the missive Sanzio asked Alfani to solicit the Perugian noblewoman to pay him for a painting.

|

| Raphael, Borghese Deposition (1505-1507; oil on panel, 174.5 x 178.5; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

The question of the link between this commission and Grifonetto’s tragic end, however, remains open. Beginning in the 19th century, and especially thanks to the contribution of Jacob Burckhardt , who treated the panel in his 1860 Die Kultur der Renaissance in Italien, the tradition gained credibility that underlying Atalanta’s decision to have the panel made by Sanzio was a desire to commemorate her murdered son. This is a hypothesis that gained, over the years, great fortune.

Konrad Oberhuber was among those who accepted it, and in his 1986 monograph, he proposed identifying in the gesture of Magdalene depicted in the Transport while clutching a hand of Christ, an allusion to Atalanta’s grief over the tragic loss, rather than tracing it, as most other scholars do, to the fainting of Mary, who appears “in the background placed too far away to be involved in such exquisitely human emotions,” Oberhuber writes.

However, Anna Coliva, director of the Borghese Gallery, in an essay contained in the catalog of the 2006 exhibition she curated, Raphael from Florence to Rome, observes that the reading advocated by Burckhardt “suited rather the romantic and literary pathos of nineteenth-century taste and could force the reality of the facts, considering that perhaps Grifonetto was not even buried in the chapel.”

Then again, the choice of subject, a moment from the Passion, was entirely appropriate for an altarpiece to be placed on an altar dedicated to the Savior. But it is at the same time undeniable, even in the absence of corroboration, and still considering that the work was commissioned five years after Grifonetto’s death, that the theme of the Transport would have been absolutely effective as an allusion to Atalanta’s grief, and would have worked perfectly for a commemorative work required, precisely, by a mother mourning her son, especially in the development that Raphael made of it. Already Vasari, in fact, praising the painter’s skill in the verisimilar representation of emotions, points out how the artist in painting the work had succeeded in imagining and elaborating “the sorrow that the closest and most loving relatives have in putting away the body of any dearest person, in whom truly consists the good, honor and usefulness of a whole family.”

The dying body of Jesus appears in the foreground of the table, surrounded by five monumental figures. Magdalene comes running in (we can tell by the movement of her hair) and clasps a hand of her now lifeless master; next to the woman, to her right, appear St. John and an unidentified man ahead in age, perhaps Nicodemus or Joseph of Arimathea, or perhaps St. Peter (for whom the gold and green colors employed here for the robes are generally reserved), who clearly directs his gaze toward the viewer. At either end of the body we see Nicodemus or Joseph of Arimathea, on one side, and a handsome young man on the other, both intent on the transport. To the right of the painting, however, three women hold up the Virgin who, overcome by grief, faints. Looming over them are the crosses of Mount Calvary, the starting point of the funeral procession, while on the left, in the foreground, one of the two transporters already has one foot resting on the steps leading to the tomb, the point of arrival, whose entrance opening can be seen. In the depths, the painting opens up to a description of a hilly landscape, dominated in the upper right by what Alessandra Oddi Baglioni (and Coliva picks up on this suggestion) identifies as the castle of Antognolla, a possession of the Baglioni household.

|

| Detail of the group on the left |

|

| Detail of the young man in the center, presumed portrait of Grifonetto Baglioni |

|

| Detail of Maria’s fainting spell |

So the narrative composition of the event is divided into two poles, the transport of the body and the fainting of Mary, separated by the presence of one of the transporters, the young man, whose beauty was understandably celebrated in the nineteenth century as one of the happiest expressions of reborn ancient perfection. A tradition as deep-rooted and evocative as it lacks concrete evidence to support it identifies this character, who occupies a pre-eminent position and for whom in fact no iconographic precedent has been traced in depictions of such a subject, with Grifonetto Baglioni himself, of whom Raphael would thus have executed an idealized portrait. Oberhuber states in this regard that this might be an acceptable interpretation, if placed, however, in a more articulate overall reading of the figure: “one is led to look intuitively for a deeper meaning; it is as if in this death scene Raphael felt the need to introduce a symbol of resurrection and future life: it is the soul of man who is saved, with Griffin, by the death of Christ.”

In any case it goes without saying that should the identification of the mysterious character with Grifonetto be proven, it would also decisively strengthen the hypothesis that the panel was explicitly requested by Atalanta with the intention of celebrating the memory of the murdered boy.

As soon as it was finished, the work was placed in the Baglioni chapel inside the church of San Francesco al Prato in Perugia. It originally formed the central part of a pictorial complex, and was accompanied by a cymatium depicting The Eternal among Angels, a frieze with Putti and Grifi, and a predella with monochrome depictions of Virtues.

However, a century later the Transportation or Deposition attracted the attention of the very powerful nephew cardinal and ravenous collector, Scipione Borghese, who with the endorsement of his uncle, Pope Paul V, ordered its removal in March 1608, having it taken from the Umbrian church at night to be taken to his villa in Rome. So many were the protests of the Perugini that the pontiff was forced to issue, a few days later, a motu proprio by virtue of which Scipione officially received the work as a gift. Moreover, to finally quell popular discontent, the Borghese family later commissioned copies of Raphael’s work, one by Giovanni Lanfranco and the other by Giuseppe Cesari, better known as Cavalier d’Arpino. Of the first painting there is no more news, so much so that it is not unlikely that Lanfranco never made it and that that same commission later passed to Cesari; of the painting that the latter executed, however, we know that it was placed first in San Francesco, then in the adjoining oratory of San Bernardino, again in San Francesco, and finally, in the second half of the nineteenth century, transferred to the present National Gallery of Umbria, where it still stands. The same museum structure today also houses the Baglioni cymatium, attributed by most to Domenico Alfani based on a design by Raphael, although it is not known with certainty whether it is the original cymatium or a copy, and the frieze also of uncertain attribution. The grisaille predella, which is instead attributed to Sanzio, was stolen by the Napoleonic army in 1797 and ended up in France until 1816, when it was returned to the Church State and acquired by the Vatican Museums.

|

| Perugia, church of San Francesco al Prato. Ph. Credit Paolo Emilio |

|

| Cavalier d’Arpino, Transporting Christ to the Sepulcher (1608; oil on canvas, 176 x 175 cm; Perugia, National Gallery of Umbria) |

|

| Domenico Alfani (attributed), Eterno e angeli (oil on panel, 64.5 x 72 cm; Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria) |

|

| Raphael Sanzio, Hope, Charity, Faith, panels of the Baglioni predella (1505-1507; oil on panel, 16 x 44 cm; Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana) |

Still according to Vasari, Atalanta a commissioned Raphael to paint the Deposition during a stay by the artist in Perugia, where he had come from Florence to work on the fresco of the Trinity in San Severo and theAnsidei Altarpiece, which allows us to date the beginning of the painting’s history to 1505. While as for the end of the work, most art historians place it close to 1507, basically lending credence to the date that is legible in the painting, along with the painter’s name, in the lower left corner next to a dandelion flower.

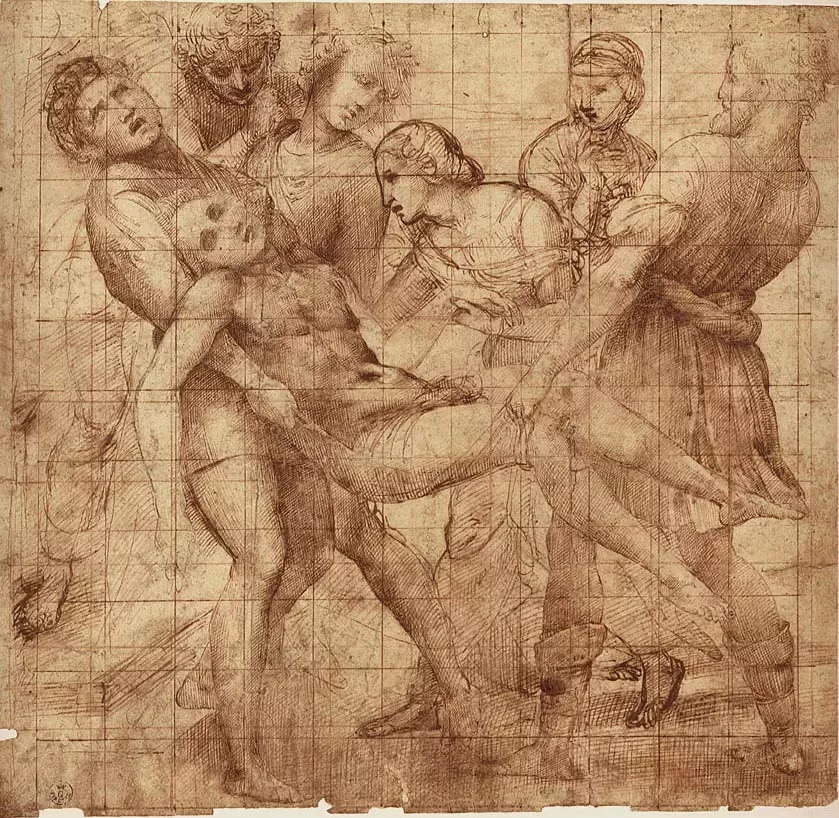

Undoubtedly Raphael worked a great deal on the composition of the work, changing his mind several times: we are told this by the numerous preparatory drawings that have come down to us, which are now kept in various museums around the world. Comparison of the various graphic studies (at least sixteen), relating to the whole scene or to specific isolated characters, has enabled art historians to reconstruct the creative process by which the artist arrived from a starting idea, that of a Lamentation, to the more articulate and dynamic Transport we see today.

The body of Jesus lies abandoned on the knees of Mary and Mary Magdalene, surrounded by other standing figures, in the two drawings, one in the Louvre and one in theAshmolean Museum, Oxford, placed at the beginning of the ideational journey. Many scholars have observed how the general structure of these early elaborations, particularly the one in the Louvre, derives with good probability from the Pietà executed by Perugino (Pietro Vannucci; Città della Pieve, c. 1448 - Fontignano, 1523), Sanzio’s master, in 1495 for the church of the convent of Santa Chiara in Perugia.

Also preserved at the Ashmolean is the drawing documenting the moment when the painter decided to introduce the movement: two figures, evidently male, are depicted in the center of the sheet in the act of laying the body on the ground, while the female figures here disappear (except for the female head study seen above alongside three other heads and a hand). This is the premise of the compositional development that will lead to the lateral displacement of almost all the women, who will be employed for the scene of the Spasimo, the fainting of the Virgin. Although it should be noted that one of the three female figures we see around Mary today, the one who supports her by standing behind her, will take her current place only near the work’s conclusion. An X-ray analysis conducted on the panel in 1995, in fact, showed that the figure was initially made in the middle of the composition, where a shrub now stands, only to be moved later, when the painting must have been nearly finished.

In an evidently later British Museum sheet, we see the body lifted and carried by two male figures; the Virgin now appears on the right along with other women, while Magdalene is depicted among the men, kissing one of Christ’s hands. The grieving face of the saint is finally lifted, turning toward that of Jesus, in a squared drawing kept in the Uffizi Drawings Cabinet that shows the final disposition of the main characters in the central scene of the painting (but the physiognomies will change and the woman previously mentioned will be moved, whom we see here still behind Magdalene).

|

| Perugino, Pietà (1495; oil on panel, 220 x 195 cm; Florence, Palatine Gallery, Palazzo Pitti) |

|

| Raphael, Study for the Baglioni Deposition (1505-1506; pen, ink and charcoal on paper, 334 x 397 mm; Paris, Louvre) |

|

| Raphael Sanzio, Study for the Baglioni Dep osition (1505-1506; pen, ink and charcoal on paper; Oxford, Ashmolean Museum) |

|

| Raphael Sanzio, Study for the Baglioni Dep osition (1505-1506; pen, ink and charcoal on paper, 230 x 319 mm; London, British Museum) |

|

| Raphael Sanzio, Study for the Baglioni Dep osition (1505-1506; pen and ink, black stone?, red stone, pen and stylus squaring, partial stippling, 290 x 297 mm; Florence, Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

So the subject of the panel becomes a Transportation to the Sepulcher, which unlike the theme chosen in Raphael’s early phase, a Lamentation or Lamentation over the body of Christ, is narrative in character, and not purely contemplative as the tradition of altarpieces dictated at the time. In other words, here the Urbino painter chose to narrate a story, alluding to its beginning (which we can place at the foot of the cross we see in the upper right corner) and its conclusion (in the tomb whose steps can be glimpsed), and to do so he put into action characters expressing emotions, moving and interacting with each other. All this took the place of a traditionally static representation designed to serve as a meditative cue for the faithful.

The narration of sacred episodes, often scenes from the Passion, was usually reserved for the predella, and yet, as noted above, in the case of the work under discussion, Raphael decided to disregard even this principle, decorating the predella with depictions of Virtues.

While, therefore, the creation of the Transport involves the overcoming of an entrenched practice, it constitutes a turning point in the context of the young Urbino painter’s artistic career, since it is his most complex composition among those followed before the frescoes in the Vatican Stanze in Rome.

Among the iconographic sources the artist looked to in constructing the new scene is a well-known pictorial work by Michelangelo. At about the same time, Sanzio and Buonarroti executed three important works for the wealthy Florentine Doni family: portraits (we do not know whether made on the occasion of their wedding or shortly thereafter) of Agnolo and his wife Maddalena Strozzi, and the circular painting on panel depicting the Holy Family, better known as the Tondo Doni. In the latter Michelangelo painting, which Raphael certainly had the opportunity to see, given his professional relationships with the owners, the Madonna is depicted with her torso in a twist, in the act of taking in her arms the Child, who is entrusted to her by St. Joseph. Her posture is very similar to that which Raphael would later have the pious woman assume in the Deposition as she crouches, turning around trying to support the unconscious Virgin behind her.

And even with regard to the main figurative core of the composition, the actual transport, Michelangelo’s influence cannot be ruled out. It has been hypothesized that Raphael had the opportunity to travel to Rome even before 1508 (when he was called there by the Pope to fresco the Vatican Stanze), and on the occasion of that hypothetical Roman sojourn, the artist may have seen the celebrated Pieta Vatican that Buonarroti had sculpted for Cardinal Jean de Bilhères, allowing himself, perhaps, to be inspired by the definition of Christ’s dead body, and taking up the cut-off position of the body, the spread feet, and the very effective abandoned arm. Then again, if even Raphael had not seen the sculpture from life, it is not unlikely that he was joined by drawings reproducing it, which could be said of other Roman works as well.

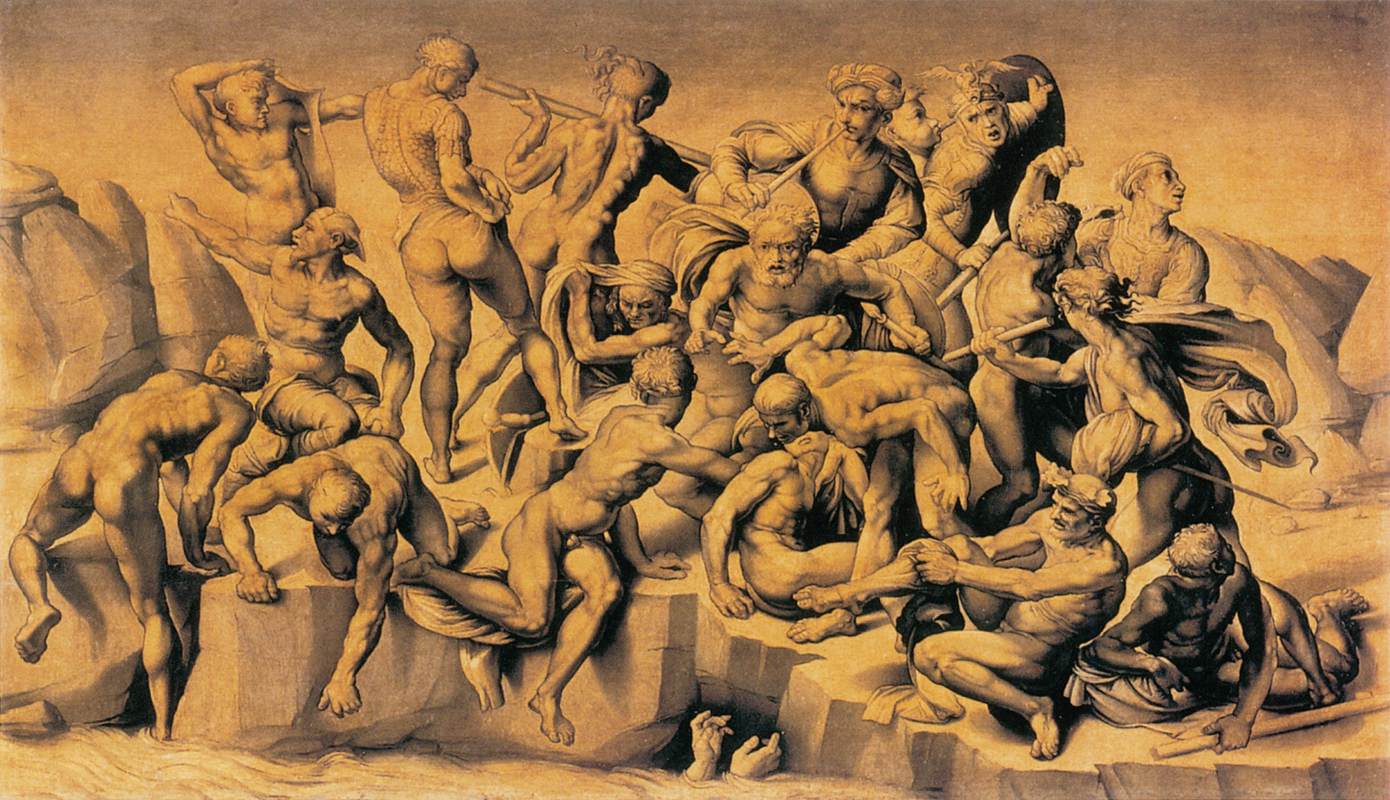

In the nineteenth century, Herman Grimm in his Das laben Raphaels first proposed another very interesting comparison, that between the funeral procession painted by Raphael in the Baglioni panel and the transportation of Meleager’s body as it appears carved on the caskets of some ancient Roman sarcophagi, of the type of the one kept in the Vatican. From these specimens the painter may have inferred the way of arranging the moving figures around the body, the posture of the corpse, and, again, the “death row.” Starting from this suggestion, the hypothesis of the identification in this kind of artifacts, of the main iconographic source for the transported Christ of Raphael’s painting had a great following in later studies.

In particular, in his contribution to the aforementioned catalog edited by Coliva for the 2006 exhibition, Salvatore Settis points out that from a sarcophagus fragment in the Capitoline Museums, the Urbino artist may also have drawn the gesture of Magdalene clutching a mando of Jesus , a gesture that in Roman marbles is performed by the pedagogue of the late Meleager.

Finally, another important precedent is to be found in an engraving by Andrea Mantegna datable to the 1570s (the fact that Raphael actually came into contact with the print is evidenced by a drawing that reproduces it on two sheets of the Venetian Libretto, a collection of studies and sketches now mostly attributed to a close and anonymous collaborator of Sanzio). In Mantegna’s engraving we see the sacred body lying on a sheet to facilitate its transportation, while the structure of the scene also involves the division of the scene into two nuclei, Mary’s transportation and fainting (also here placed under the crosses of Golgotha), arranged at either end. Also interesting is the isolated figure of St. John, whom the Paduan artist depicts with joined hands not far from the pious women. The saint has very similar placement and attitude in the Louvre drawing made by Raphael at the beginning of his design for the Baglioni Altarpiece, while he was still pondering the theme of the Lamentation. When the painter later changed the composition to a Transportation, the figure was moved to the left, where we see him today; he still shows clasped hands and, although he now occupies a marginal position, his figure effectively contributes to the tragic and solemnity of the scene, as noted already by Vasari: “crossing his hands, he bends his head with a manner to move what is hardest to pity.”

|

| Michelangelo, Tondo Doni (1506-1507; tempera grassa on panel, 120 cm diameter; Florence, Uffizi Gallery). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Michelangelo, Pieta (1497-1499; Carrara marble, 174 x 195 x 69 cm; Vatican City, St. Peter’s) |

|

| Roman art, Fragment of sarcophagus with the transportation of the body of Meleager (mid-2nd century AD; Luna marble, 96.8 x 22.2 x 119.1 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

|

| Raphael, The Death of Meleager (c. 1507; pen and ink, lead point, 271 x 332 mm; Oxford, The Ashmolean Museum) |

|

| Andrea Mantegna, Deposition of Christ (1570s; burin engraving, 446 x 304 mm; Chiari, Pinacoteca Repossi) |

Charles M. Rosenberg in a 1986 article, Raphael and the Florentine Istoria, recalled how, when making the painting, Raphael must have been faced with the need to take into account the expectations of a large audience. In the first place, his work would have had to satisfy the client Atalanta Baglioni, with whom he undoubtedly agreed on the theme, although we do not know what was stated in the contract because it has not reached us. In any case, it is not certain that she played a role in the transition from the Lamentation to the Transport, although in all likelihood she was informed of it in good time, because both subjects indistinctly could have worked just fine on the altarpiece of a family chapel, and possibly fulfilled her desire to commemorate her son.

The work would then have to be approved by the monks of St. Francis, although, considering the power of the Baglioni family, the religious would hardly have refused to go along with their wishes. Above all, Rosenberg notes, in its author’s intentions, the painting had to convince Florentine artists and patrons. As mentioned above, it is generally accepted that the work (conception and execution) dates to the years from 1505 to 1507 or at most to the beginning of 1508; during this time the artist was often in Florence, where he worked for several families of the rich bourgeoisie (the Taddei, the Doni, the Canigiani, the Dei) producing mainly portraits or splendid Madonnas.

The letter of introduction in which Giovanna Feltrìa della Rovere is said to have recommended the young Raphael to Pier Soderini, gonfalonier of Florence, dates back to 1504; however, the authenticity of the text, of which an eighteenth-century transcription has come down to us, is now considered doubtful by several scholars.

In any case, Raphael, who had certainly been in Florence before, moved more permanently to the city, although continuing to move when necessary, starting in the very year to which the above-mentioned letter would be referred, as evidenced by his pictorial production and as reported by Vasari.

The biographer and painter from Arezzo tells us that after executing the Marriage of the Virgin, Raphael was invited to Siena by Pinturicchio, who asked him to help him with the frescoes in the Piccolomini Library. Soon, however, the young Urbino, reached by news of what Leonardo and Raphael were planning for the east wall of the Sala del Gran Consiglio in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio, would leave Siena to go and see for himself. And once he arrived “because he liked the city no less than those works which seemed divine to him, he resolved to dwell in it for some time.” In any case, Vasari adds, the artist in Florence studied with devotion both the new and the old masterpieces, but he also found time to work on the project of the Transport, which, as already mentioned, had been commissioned from him in 1505 during a stay in Perugia, a city he had then left again to return to Florence.

It was thus under the influence of the rich and fermenting cultural context of Florence that Raphael devised the Baglioni panel, eventually orienting himself toward the depiction of an articulate and dynamic scene that would allow him to test himself in the dramatic rendering of movements and motions of the soul, and to demonstrate his narrative skill to the competitive Florentine artistic community, and to the many potential clients.

We mentioned that in 1504 in Florence Leonardo and Michelangelo were both working on frescoes for the Palazzo Vecchio, which were to depict the Battle of Anghiari and the Battle of Cascina, respectively, never completed. The projects involved the visual telling of two war events, staged by employing monumental bodies in action.

We know that the young painter was able to fulfill his desire to see the cartoons from life, as we possess some of his drawings taken from the very works of the masters. Particularly interesting is a sheet, preserved at the Ashmolean in Oxford, on which we see an excerpt from the Battle of Anghiari, alongside two studies of male heads for the fresco he would have executed in San Severo in Perugia, one of which, the head of an old man, evidently recalls one of the characteristic types from Leonardo’s drawings.

|

| Francesco Morandini known as Poppi (?), Struggle for the Standard, copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s Battle of Anghiari (1563?; oil on panel, 83 x 144 cm; Florence, Palazzo Vecchio, on deposit from the Uffizi Galleries) |

|

| Bastiano da Sangallo, Battle of Cascina, copy from Michelangelo’s cartoon (1505-1506; oil on panel, 77 x 130 cm; Norfolk, Holkham Hall) |

|

| Raphael Sanzio, Sketch of the Battle of Anghiari by Leonardo da Vinci (c. 1503-1505; silverpoint drawing, 211 x 274 mm; Oxford, Ashmolean Museum) |

Many of the scholars who have dealt with the Baglioni Altarpiece have dwelt on remarking on the influence that Michelangelo’s and Leonardo’s own grand designs for the Palazzo Vecchio exerted on the young Sanzio during the years he was engaged with the painting. Not least because it must be considered that in 1506 both Tuscan artists abandoned the undertaking, and this may have prompted Raphael to consider it possible that the task of finishing the frescoes, or even starting the work all over again, was entrusted to him. It is possible, then, to speculate that this prospect contributed to the decision to so radically alter his initial design for the Baglioni Altarpiece, updating it, making it more suitable, as Coliva writes, to “respond to the challenges opened up by the two supreme artists.”

In fact, in a letter sent from Florence on April 27, 1508, Sanzio asked his uncle Simone Ciarla to urge the duke of Urbino, Francesco Maria della Rovere, to recommend him (a second time, if Vittoria Feltrìa’s missive were authentic) to Pier Soderini, in order to get him work assignments of greater weight than those he had been doing up to that point.

It is very interesting the chronological proximity between the writing of this message for his uncle and the conclusion of the Transport, in the success of which Raphael probably placed great hopes, aware not only that he had produced a remarkably innovative work, but also that he had taken a decisive step in the direction of the highest achievements of the pictorial art of his time.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.