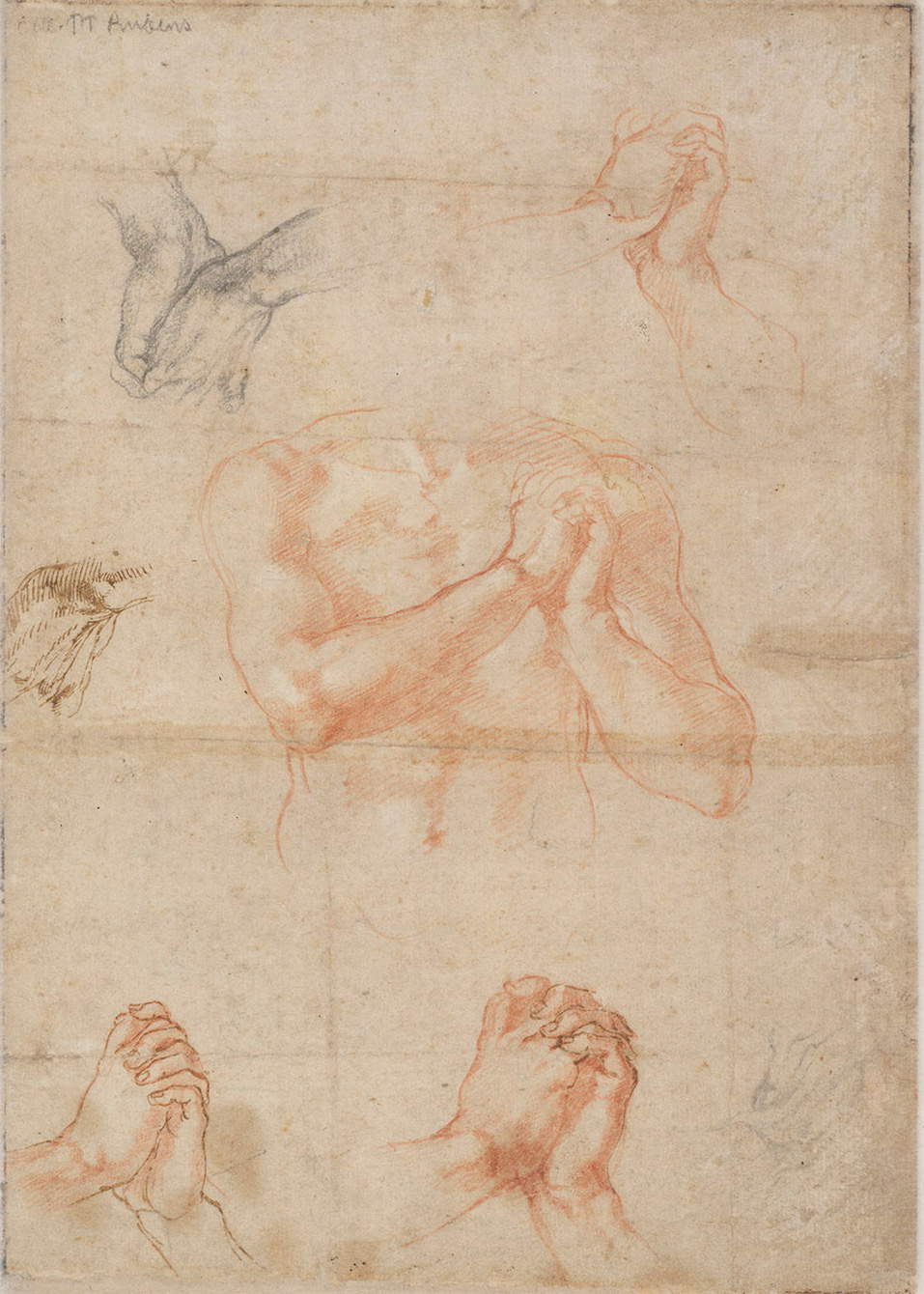

The Albertina in Vienna preserves a drawing, widely attributed to Michelangelo, with some studies of intertwined hands: in the exact center of the sheet, well detached from everything else, stands a male torso, with arms folded and hands joined at chest height. This is the only surviving evidence that remains to us of Michelangelo’s association with Sebastiano del Piombo for the Pietà that was commissioned from the Venetian by the cleric of the Apostolic Chamber, Giovanni Botonti, for the church of San Francesco in Viterbo, and which was finished by May 1516. It is probable, however, that Michelangelo had also provided Sebastiano with a cartoon: this is attested by Giorgio Vasari in his Lives, not without a hint of veiled sufficiency, when the Aretine states that that painting, “if well it was with much diligence finished by Sebastiano who made there a tenebroso paese molto lodato, l’invenzione però et il cartone fu di Michelagnolo.” Vasari did not like Sebastiano del Piombo, and in these lines, in which the Venetian is almost made to pass as a mere colorist, a luxury comprimario who merely finished with diligence an invention of the unparalleled master, his at least ambiguous attitude toward “Sebastiano Viniziano” emerges with blatant evidence.

How much Michelangelo is there, then, in Sebastiano’s Viterbo masterpiece? First of all, it is necessary to premise that the Pietà is the first chapter of a close alliance between the Venetian and the Tuscan, the reasons for which can be found in Michelangelo’s discomfort with the growing successes of his younger rival Raphael, who until the end of the twentieth century had been younger rival Raphael, who from the moment of his arrival in Rome had obtained, from wealthy Roman patrons and the intellectuals who frequented them, an attention and support that would provoke the reaction of Michelangelo, who feared being surpassed by the Urbino. An alliance to propose a totally new product to Roman clientele: “the excellence of color and the perfection of design,” as scholar Costanza Barbieri has effectively summarized. Sebastiano is the public face of the partnership: it is he who maintains relations with clients, it is he who ’signs’ the paintings, it is he who exposes himself to the judgments of critics. Michelangelo, on the other hand, works hard on the design and, when he can, publicly supports his friend.

|

| Michelangelo, Study of Hands and Male Torso (c. 1512; sanguine, black chalk, pen on paper, 272 x 192 mm; Vienna, Albertina, inv. 120v) |

|

| Sebastiano del Piombo, Pieta (1512-1516; oil on panel, 190 x 245 cm; Viterbo, Museo Civico) |

This collaborative relationship thus begins with the Pietà now preserved and displayed, somewhat sacrificed (the accurate illustrative panels partly compensate), in a small room in the Museo Civico in Viterbo. It is one of the most powerful images of the 16th century: Guido Piovene, in his Viaggio in Italia, had described the Pieta as a “stormy nocturne, riven by deep blues, illuminated by the moon and furnace glow.” In a gloomy countryside, in the middle of the night, with only moonlight to make its way through a blanket of clouds and flashes of varying intensity on the horizon, a strong Virgin of masculine proportions sits before the body of her son, mourning him with dignity. Her torso is masculine, derived from the idea of the Albertina sheet, her arms are muscular, her features reminiscent of the Sibyls in the Sistine Chapel vault. He wears a blue bodice, an ultramarine robe, his head is covered by a white veil, his hands are entwined at the side, his neck is powerful and massive, his face solid and vigorous, his gaze rises to heaven. Christ is lying on the shroud, naked except for the loincloth that wraps around his pelvis: it is the base of the pyramid that has his mother’s head as its apex. Their figures, immersed in the solitude of the night, are not naturally lit: we see them emerge from the landscape, almost detached, enveloped in a light that is not that of the landscape. And the iconography does not follow the Nordic tradition of the Vesperbild, which in Italy had great fortune and found its highest example in Michelangelo’s Pietà Vaticana : in Sebastiano del Piombo’s painting, the mother does not receive the child in her womb, but the relative nevertheless finds himself before a tragic representation. The nocturnal landscape of clear Giorgionesque inspiration, a spectacular result of Sebastiano’s brushwork, emphasizes the drama of the moment: nature, Rodolfo Pallucchini has written, in this painting moved by the “truly heroic” intention that was perhaps “suggested to Sebastiano by Michelangelo,” plays the role of the chorus of the tragedy. For Pallucchini, however, it is a chorus that appears to be detached from the “figures of Christ and the Mother conceived as solid plastic masses, where the color is petrified in a flow of blue grays and dark turquoises and coagulates in the milky luminosity of the sheet,” a chorus unable to act as a synthesis, and in his opinion unconvincing: it was configured, if anything, as “a universe of living atmospheres, frayed, flashing with light,” ahead of Tintoretto’s nocturnes.

This apparent imbalance is to be read, according to Barbieri, in relation to the painting’s tormented conservation history: the backdrop has suffered the ravages of time, but not to the point of preventing the viewer from marveling at those flashes, those snapping flashes that emerge among the ruined buildings, among the plants, beyond the hills. It is nature that participates in the tragedy. It is not a sunset that can be seen on the horizon: that reddish glow on the left is perhaps a fire, or an explosion as Mauro Lucco has argued, while the blaze on the right looks like the flash of a thunderbolt announcing a storm, like the wind that stirs the trees. The figures of Christ and Mary, however, are untouched by nature’s fury. And then there is a reassuring detail, that of the moon dissipating the clouds to brighten the landscape.

Sebastiano del Piombo, evidently on the basis of a precise program, suggests to the faithful all the moments of the Passion: the Calvary referred to by the brambles and the severed trunk near which the Virgin sits, death, the waiting for the Sabbath and, finally, the resurrection, symbolized precisely by the moon, since Easter falls every year on the Sunday following the first full moon of spring. According to Barbieri, however, Sebastiano also included in the Pietà a devotional motif typical of Viterbo, the cult of the Madonna Liberatrice, a holiday established in 1334, a few years after the city managed to overcome a violent cloudburst by praying to the Virgin. The memory of the Madonna who, in May 1320, had freed Viterbo from the storm must probably have surfaced from the Venetian’s painting, especially since the patron was very devoted to the Madonna Liberatrice: and Sebastiano del Piombo perhaps used all his talents as a formidable colorist to implicitly suggest the memory of the miracle to the faithful of Viterbo, who would have had no difficulty in recognizing it.

The initial question was left hanging: how far did Michelangelo’s contribution go? The majesty and monumentality of Sebastiano’s figures immediately refer back to many of Michelangelo’s precedents, both in painting and in sculpture, and this is also true of certain details: see, for example, how Christ’s left hand recalls that of Adam in the vault of the Sistine Chapel, but the same could be said for the figure itself. And there is no valid reason for doubting the existence of a cartoon to this day that has been dispersed, nor for not attributing the project to Michelangelo. Yet, Sebastiano had already proven in Venice that he fully understood Michelangelo’s instances. The grandiose proportions of these figures can already be seen in his early paintings: the example of the altarpiece of St. John Chrysostom is worth noting. A torso movement similar to that of the Virgin is discerned in nuce already in the Portrait of a Woman as a Wise Virgin in the National Gallery in Washington. The association could have been initiated because Sebastiano had already shown great confidence in the motifs inferred from Michelangelo: and rare were the artists capable of measuring themselves with the Tuscan genius without being bent, vanquished, overwhelmed by it. Sebastiano, then, is not a mere diligent executor: he is an artist who makes Michelangelo’s invention his own, understands it, and interprets it according to his own sensibility, shaping the figures with a very soft and elegant chiaroscuro and with refined luministic refinements. If the strength of that extraordinary tenebrous landscape, the virtuosity of the coloristic effects were not enough. And the Pieta was greatly appreciated by contemporaries as soon as it was exhibited: after all, nothing like it had ever been seen in Rome.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.