Of Andrea del Sarto (Andrea d’Agnolo di Francesco di Luca di Paolo di Migliore Vannucchi; Florence, 1486 - 1530), Giorgio Vasari said that he was the painter who was able to create figures “without errors”: his figures were “of supreme perfection” as Andrea del Sarto’s main characteristic was his ability to always create formally faultless, harmonious, well-balanced compositions: a classical painting, which set a school (for centuries artists, even great ones, copied his works to learn how to draw) and which with its luminous colors and light effects also formed an indispensable basis for the early Mannerist painters. Andrea del Sarto worked almost always in Florence, trained in the workshop of Piero di Cosimo (Pietro di Lorenzo; Florence, c. 1461 - 1522), but well lent to studying more up-to-date models, namely those of Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael Sanzio. Far from the monumentality of his contemporary Fra’ Bartolomeo (to whom, however, he came close in the last stages of his career), he knew how to create compositions always endowed with grace, elegance and balance.

Vasari again recounts, in his Lives, that Andrea, at the age of only seven, was sent to a goldsmith’s workshop after he had been in a school of letters for some time: however, it seems that little Andrea was much more at ease drawing than handling the tools of goldsmithing, and this ability of his was reportedly noticed by a painter who at the state of our knowledge is almost unknown (a certain Giovanni Barile), who suggested that he abandon the art of goldsmithing and give himself to painting instead. Given the great progress Andrea made in Giovanni Barile’s workshop, the latter introduced him to Piero di Cosimo, then one of the greatest artists in Florence, and so he passed into his workshop. Andrea, still in Piero di Cosimo’s workshop, had the opportunity to study Leonardo’s and Michelangelo’s cartoons for the Salone dei Cinquecento (read more about Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina here and more about Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari here), when they were displayed in the Sala del Papa in Santa Maria Novella, in the convent: the encounter with the two great artists was of extreme importance for Andrea del Sarto, because after an initial phase linked to the Florentine tradition, his art would turn toward that of the mature Renaissance, especially that of Leonardo and Raphael.

It seems that the young Andrea, in the Sala del Papa, met Franciabigio (Francesco di Cristofano; Florence, 1484 - 1525), another important artist of the time, and became his friend, and Vasari relates an anecdote: Andrea del Sarto is said to have confided to Franciabigio that he was tired of the now famous character quirks of Piero di Cosimo, and wanted to break free from his master. Franciabigio, who was instead a pupil of Mariotto Albertinelli, told him that he too felt this need, so the two artists decided to leave their workshops and set up one together, and together they worked through the first part of their careers. Thus began the career of one of the greatest artists of the mature Renaissance.

|

| Andrea del Sarto, Self-Portrait (1528-1529; detached fresco, 51.5 x 37.5 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery, Vasari Corridor) |

Andrea d’Agnolo (his full name is Andrea d’Agnolo di Francesco di Luca di Paolo del Migliore Vannucchi) was born on July 17, 1486, to Agnolo, who was a tailor by trade (hence the name by which the artist is now universally known) and Costanza di Silvestro, the daughter of a tailor. Andrea’s brother, Francesco d’Agnolo known as lo Spillo, would later become a painter as well, though not to Andrea’s standards. He was placed in the workshop of the half-unknown painter Giovanni Barile, but soon moved on to the workshop of Piero di Cosimo. He also trained by copying the works of Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. In 1508 we find him enrolled in theArte dei Medici e degli Speziali, the professional guild to which artists enrolled. Around the same year he produced the first works that have come down to us, including theInitiation of Icarus in Palazzo Davanzati. In 1509, the friars of the Convent of the Santissima Annunziata in Florence commissioned Andrea to paint the cycle of frescoes in the Chiostrino dei Voti: the paintings, whose theme is the Stories of St. Philip Benizzi, were completed in 1510, and two more frescoes(The Journey of the Magi and the Nativity of the Virgin) would be added in 1511 and 1514, respectively.

In 1515, Andrea began work on the Chiostro dello Scalzo, where he was engaged in a decorative cycle with the Stories of the Baptist, completed in 1526. One of his best-known masterpieces dates back to 1517: the Madonna of the Harpies, painted for the church of San Francesco dei Macci and now in the Uffizi Gallery. In the same year he married Lucrezia di Bartolomeo del Fede, who would later become a model for his works. In the same period he made the paintings for the Borgherini bridal chamber: the Stories of St. Joseph (theInfancy and Joseph Interprets Pharaoh’s Dreams). The following year, Andrea del Sarto went to France where he worked for King Francis I: of the works he created transalpine we are left with only the Charity preserved in the Louvre. In 1519 Andrea returned to Florence, resumed work on the Chiostro dello Scalzo and began the Tribute to Caesar fresco in the Villa Medicea at Poggio a Caiano: left unfinished, it was to be finished by Alessandro Allori. In the same year he was commissioned to paint theLast Supper for the convent of San Salvi. However, the San Salvi cenacle would not be finished until ten years later, in 1529.

Shortly thereafter, in 1523, a plague epidemic broke out in Florence, and the artist, in order to escape it, moved first to Mugello, where he executed one of his major masterpieces, the Pietà of Luco (now in the Pitti Palace), then perhaps also went to Venice. He returned to Florence the following year, and in 1525 he was again at work at Santissima Annunziata, where he executed the fresco of the Madonna del Sacco. In 1528 he executed, for Giovanni Maria Canigiani, general of the Vallombrosian order, the Vallombrosa Altarpiece, intended for the abbey of Vallombrosa (today it is in the Uffizi instead). He painted in 1530 his last work, the Poppi Altarpiece, for the church of San Fedele in Poppi, Casentino. The artist disappeared in the same year, in Florence, between September 28 and 29, during a plague epidemic that broke out during the siege of Florence.

|

| Andrea del Sarto, Madonna of the Harpies (1517; oil on panel, 207 x 178 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Andrea del Sarto, Pietà of Luco (1523-1524; oil on panel, 238 x 198 cm; Florence, Palatine Gallery, Palazzo Pitti) |

A journey to discover Andrea del Sarto’s art can start with the masterpiece of the first phase of his career, the Madonna of the Harpies. It was commissioned from him by the nuns of the convent of San Francesco dei Macci in Florence in 1515. The date 1517, the year Andrea completed the work, is inscribed on the base on which the Madonna rests. Later, in 1703, Prince Ferdinando de’ Medici, seeing the altarpiece on the occasion of a visit to the convent, was so fascinated by it that he proposed to the nuns that they finance the restoration of the church in exchange for the painting, which therefore entered the Medici collections, first at the Pitti Palace and then at the Uffizi. The bizarre name “Madonna of the Harpies” derives from the fact that Vasari interpreted the figures on the base of the Madonna’s throne as two harpies, but they are actually locusts: in theApocalypse of John this term is used to refer to beings that had women’s hair, lion’s teeth, iron armor, and scorpion wings and tails. The first to arrive at this insight was art historian Antonio Natali, who explained these figures by relating them to the presence of Saint John, the saint on the right, author of Revelation. The other saint, on the left, is instead Saint Francis, the saint of the convent of the commissioning nuns. The painting gives an idea of Andrea del Sarto’s typical stylistic signature: the artist, in particular, works a fusion between the three greats of the mature Renaissance, namely Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo, achieving, however, a degree of maturity and harmony between the various elements such as he had not yet succeeded in up to this time. The characters are marked by Raphaelesque grace (see, for example, the face of St. John, exemplified on Raphael’s faces), just as Raphaelesque is the Madonna, while the sense of grandeur and monumentality is inferred from Michelangelo, and the use of the technique of sfumato, which here touches one of the peaks in Andrea del Sarto’s art, refers directly to Leonardo da Vinci. The composition is symmetrical, traditional, composed and calm, achieving the formal perfection so praised by Giorgio Vasari, to the point of having him write that Andrea del Sarto’s figures are “without error” and “of supreme perfection.”

Another key painting for understanding Andrea del Sarto’s poetics is the Pieta di Luco: it is speculated that it was executed after a plausible trip to Venice, because the landscape has changed considerably from those the painter had painted so far. In particular, the landscape becomes more natural and is reminiscent of those seen in paintings by artists such as Giorgione and Titian Vecellio: the grotto of the sepulcher on the left in particular recalls certain Giorgionesque solutions, such as the cliff seen in the famous painting of the Three Philosophers preserved in Vienna. The colors also seem to take up the lesson of Venetian tonalism, for they are much warmer and brighter in the foreground and tend to become cooler as one moves towards the background of the painting (these typical characteristics of tonal painting). Instead, the scheme is taken from Perugino, and in particular from his Lamentation over the Dead Christ, made for the convent of Santa Chiara in Florence and now preserved in the Pitti Palace: the scheme is identical, as is the pose of Christ, in the center with his bust supported by St. John. Andrea del Sarto’s work, however, is much more modern: in the face of less gentleness and less idealization, one notices not only a more natural landscape, but also more studied and truer expressions, as well as much more naturalistic connotations, in which real portraits are concealed (for example, St. Catherine has the features of the commissioner of the work, Caterina di Tedaldo della Casa, abbess of the convent of St. Peter for whom the work was intended). Here the reference is rather obvious in that the saint is the one named after the patron. There is great sweetness, however, also in certain passages of this composition by Andrea del Sarto, as for example in the face of Magdalene, who manifests a very composed and dignified sorrow, and has beautiful features but of a natural, not ethereal beauty, and in this one can glimpse the influence of Leonardo.

Among the last works of the artist’s career is the Vallombrosa Altarpiece: this is a dossal, that is, an altarpiece made from a single panel. The saints represented are, on the left, St. Michael the Archangel and St. John Gualbert, while on the right are arranged St. John the Baptist and St. Bernard degli Uberti, and in the center are two angels plus a gap left by a compartment that has been lost. St. John Gualbert was the founder of the Vallombrosian order and St. Bernard of the Hiberti one of the most important Vallombrosian monks. In the last years of Andrea del Sarto’s career we see a rapprochement to the manner of Fra Bartolomeo, already present, moreover, in the Pietà of Luco, since Fra Bartolomeo had also executed a Pietà in similar tones, and this rapprochement allows Andrea del Sarto to give a greater monumentality to the figures, which here stand out only against a blue sky. The pose of St. Jacopo, similar to that of saints who appear in other late paintings by Andrea del Sarto, shows how the artist tends to repeat the same patterns in the latter part of his career, albeit with great modernity and naturalness as evidenced by the poses and looks of the two beautiful children. The repetition of patterns also returns in Andrea del Sarto’s last work, the Poppi Altarpiece, a work of 1530 that is in the Pitti Palace, where the compsitive register is divided into two identical parts, the upper one with the Madonna high up in the clouds, and the lower one with the saints (Bernardo degli Uberti, Fedele di Como, St. Catherine of Alexandria, and St. John Gualbert). In this painting, moreover, there is a greater juxtaposition to the soft but bright colors of Pontormo’s art.

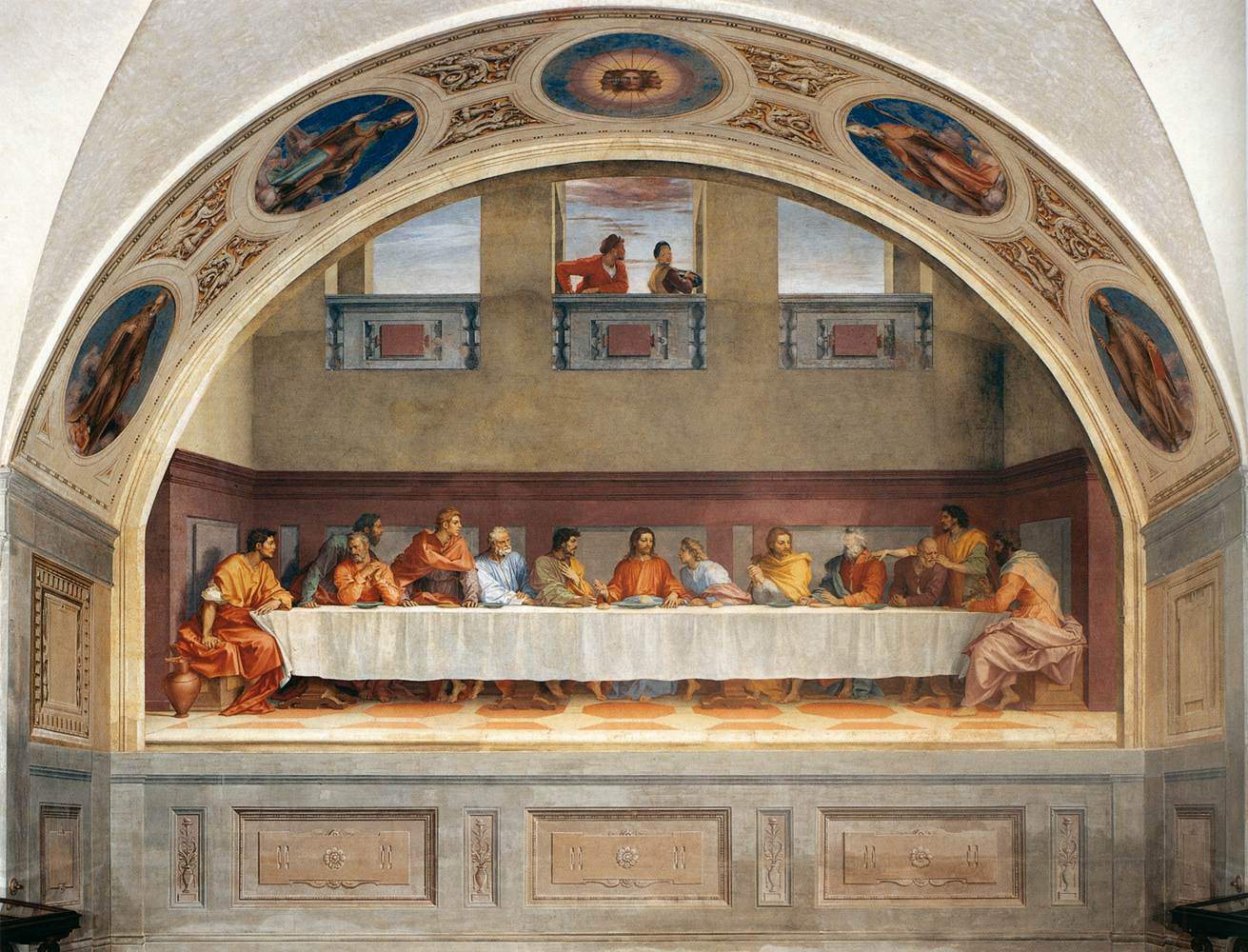

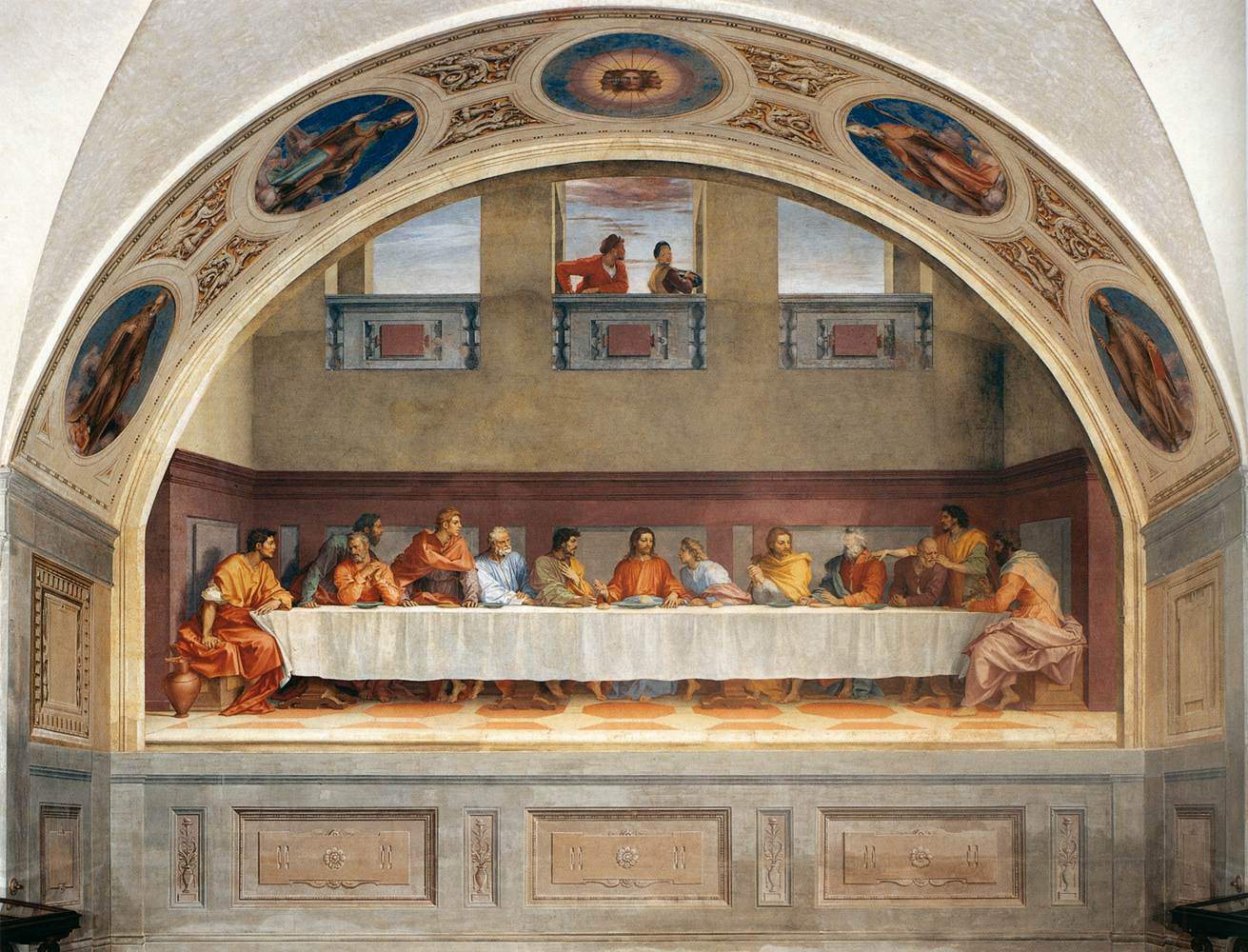

Finally, it is necessary to mention one of his best-known masterpieces, the Last Supper of San Salvi: the work was commissioned from him in 1511, when the abbot of the convent of San Salvi, Ilario Panichi (a Vallombrosian monk), decided to entrust the task to Andrea del Sarto, who nevertheless began working on it in 1519 to complete the work in 1529, but it can be assumed, given the documents that have come down to us, that the realization of the Last Supper fresco was concentrated around the mid-1520s. Moreover, an anecdote is told around this masterpiece: during the infamous siege of Florence in 1530, when the imperial soldiers precisely besieged the city in order to make the republicans desist and thus allow the Medici to return (Emperor Charles V and Pope Clement VII, born Giuliano de’ Medici, had become allies again after the sack of Rome, and the emperor ensured that the city of Florence would return under Medici control), a great many of the works outside the walls of Florence were destroyed, but the soldiers spared Andrea del Sarto’s work because they were captivated by its beauty. Andrea del Sarto’s LastSupper is a work of considerable importance because it demonstrates the reception in Florence of the innovations introduced by Leonardo with his Milanese cenacle, that of Santa Maria delle Grazie(read an in-depth discussion of the work here), in terms of rendering the emotions of the characters’ souls. We note, therefore, that Andrea del Sarto makes a study of the psychological rendering of the characters, although the dramatic charge appears much toned down compared to Leonardo’s: this is because excessive drama was not at all compatible with the canons of formal perfection and classicism of an artist like Andrea del Sarto. His narrative is therefore less tragic but more intimate, Judas’s betrayal no longer becomes a cause for strong astonishment as it did in Leonardo, but becomes almost a cause for reflection: if Leonardo had focused on strong feelings, if one could read astonishment that also gave rise to heated discussions such as that of the last three apostles on the right, the feeling that prevails in Andrea del Sarto is instead sadness, bitterness: this characteristic is what makes this fresco great and at the same time differentiates it from that of Leonardo da Vinci. However, almost as if to downplay the event, the artist also inserts a new and original detail, that of the two servants at the top, facing the balustrade, one of whom, moreover, does not even seem interested in the scene and looks the other way. Finally, in spite then of the fact that the apostles are individually characterized, none of them loses that grace and classical composure that constituted a distinctive feature of Andrea del Sarto’s art. The fresco of theLast Supper is located under a large arch that was decorated by the artist with five medallions: the one in the center depicts the Trinity, while the other four bear depictions of as many patron saints of the Vallombrosian order. The complex housing the fresco was, moreover, musealized in 1981.

|

| Andrea del Sarto, Stories from the Infancy of Joseph (c. 1515-1516; oil on panel, 98 x 135 cm; Florence, Palatine Gallery, Palazzo Pitti) |

|

| Andrea del Sarto, Vallombrosa Altarpiece (c. 1528-1529; oil on panel, 200 x 250 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Andrea del Sarto, Last Supper (1519-1529; fresco, 525 x 871 cm; Florence, Museo del Cenacolo di Andrea del Sarto) |

Andrea del Sarto’s major works are all found in Florence, concentrated in even a fairly small area of the historic center. At the Uffizi there are several masterpieces such as the Madonna of the Harpies, the Lady with the Basket of Spindles at the Palatine Gallery in Palazzo Pitti it is possible to see the Stories of Joseph, the Dispute of the Trinity, the Vallombrosa Altarpiece, the Pietà of Luco, thePanciatichi Assumption, the Gambassi Altarpiece, and other works are found at Palazzo Davanzati, the National Museum of San Marco, and the Museum of Orsanmichele, not forgetting sacred places such as the Chiostrino dei Voti in the Basilica of Santissima Annunziata and the Chiostro dello Scalzo. Salvi’s Last Supper, in addition to housing theLast Supper, his largest and most important fresco, also preserves two early works, the Noli me tangere and the Five Saints. Another important fresco is the Tribute to Caesar, completed by Alessandro Allori, which can be seen in the Villa Medicea at Poggio a Caiano. Few Italian museums outside Florence preserve his works: one of the most important is the youthful Madonna and Child with St. John at the Galleria Borghese in Rome, while the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica at Palazzo Barberini preserves the Barberini Holy Family.

Several of his works can be found outside Italy: the Louvre, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Prado in Madrid, the National Gallery in London, the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, the Gemäldegalerie, the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, and the Museum of Art in Cleveland are some museums that preserve his works.

|

| Andrea del Sarto: life and works of the painter without errors |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.