We know little about Antonello da Messina (Messina, c. 1430 - 1479): indeed, the life of this great painter has few fixed points. However, what matters above all is his importance for the history of art: in fact, Antonello da Messina was the painter who, in the Renaissance, was able to bring together the north and south of Italy, giving rise to a highly original style (he was probably the greatest portrait painter of the 15th century) with suggestions from the rest of Europe as well. After leaving his homeland, Sicily, he studied in Naples in the workshop of Colantonio (Niccolò Antonio; c. 1420-Naples, after 1460), where he came into contact with Provençal and Flemish painting, from which he took his attention to detail and naturalism. To these characteristics he combined the volumetries and rigor of Piero della Francesca and, following a trip to Venice in 1475, also the delicacy of Venetian colors.

To reweave the threads of the great Sicilian artist’s journey, however, it is necessary to start in Naples: here, the accession to the throne of Alfonso of Aragon in 1442 made Naples a culturally and artistically lively city that was open to the world. The king, who also went down in history as “Alfonso the Magnanimous,” ascended the throne following the defeat of Renato d’Anjou, the last Angevin king of Naples.Renato d’Anjou himself, however, during his reign (from 1435 to 1442) did his best to try to advance the Neapolitan cultural and artistic environment. Both Renato d’Anjou and his successor were lovers of Flemish art, and artistic trends in Naples in the second half of the fifteenth century looked especially to the art being produced in Flanders, but not only: Alfonso d’Aragona, in addition to collecting works by painters such as Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, and Petrus Christus, thus destined to provide important suggestions to local artists, had brought in from Spain some artists such as Jacomart Baço (Valencia, c. 1410 - 1461), who were able to give an additional impetus to the artistic life of Naples. Also active in the Campania city for a few years were two important painters of the French school, Jean Fouquet (Tours, c. 1420 - 1481) and Barthelemy d’Eyck (Maaseik, 1420? - after 1470), who brought other important new elements to the kingdom: Barthelemy d’Eyck, in particular, transmitted elements of Provençal culture. These experiences were not decisive for the formation of a local school, but they acted on several important individual personalities, such as that of Colantonio, who knew how to merge all these cues in his art, and especially that of Antonello da Messina.

His training took place precisely in Naples, while we do not know whether he also studied at home: as anticipated, there is not much information about Antonello da Messina’s life. Moreover, the vast majority of Antonello’s paintings that have survived are dated to after 1460: therefore, since Antonello was born around 1430, we have a period of thirty years about which there is very little information. According to Giorgio Vasari’s reconstruction, Antonello received his education in Rome and Naples, and in particular the encounter with a painting by Jan van Eyck (Maaseik, c. 1390 - Bruges, 1441) that was part of the collections of Alfonso d’Aragona and that would have prompted the young Antonello to study and learn oil painting would have been decisive. Tradition has it that it was Antonello himself who brought the technique of oil painting to Italy, although this is something that cannot be known for sure. Nor is it possible to know whether Antonello was in Rome: it is known, however, also from other sources, that he resided for some time in Naples, and in particular was a disciple of Colantonio, and in Naples he was able to observe the work of the Flemish, French, Provençal, and Spanish artists who worked in the Neapolitan city. This is where Antonello da Messina’s great art begins.

|

| Antonello da Messina, Portrait of a Man (1465-1475; oil on panel, 31 x 24.5 cm; Cefalù, Mandralisca Foundation Museum) |

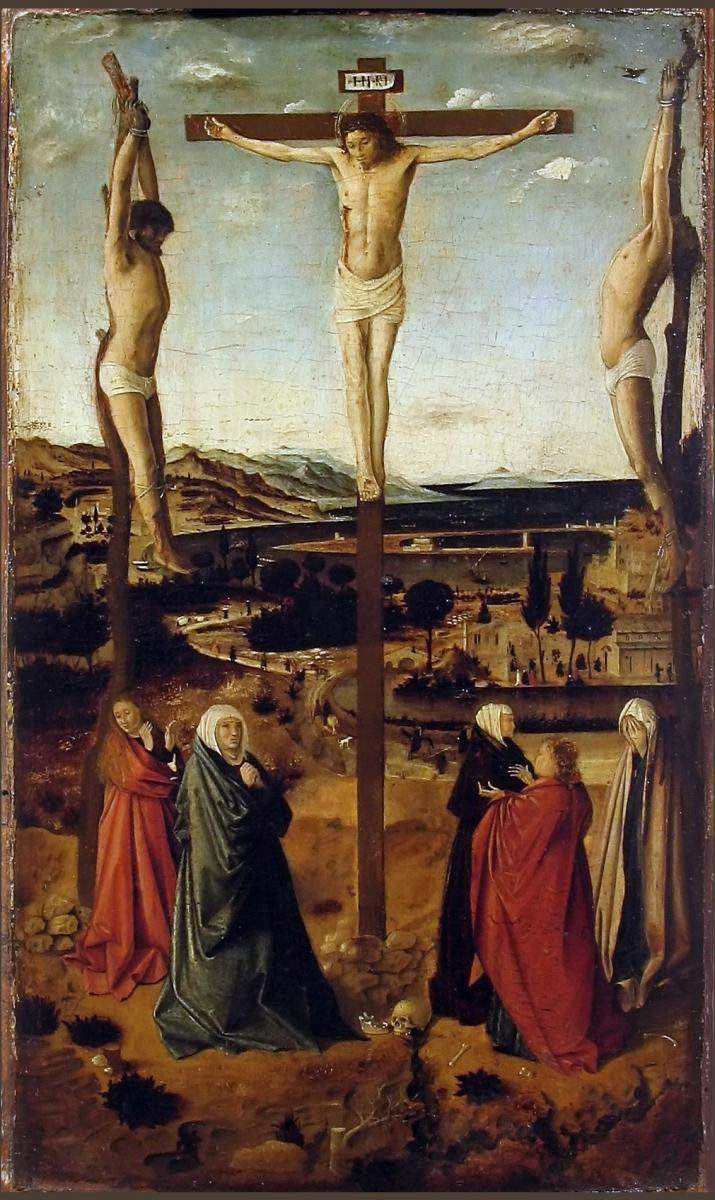

Antonello da Messina was born around 1430 in Messina, Sicily, to Giovanni de Antonio, a stonemason by trade, and Garita (probable diminutive of Margherita). It is plausible to think that his apprenticeship took place between Messina and Palermo. According to a recently discovered document, it seems that the artist, as a teenager, was also in Alcamo. Probably around 1450 he was in Naples where he carried out his apprenticeship with Colantonio. In 1457 Antonello is mentioned in some documents: we know that he is present in his hometown and has already opened a workshop. Around 1460 he painted two of his earliest masterpieces, namely the Crucifixion of Sibiu and the Salting Madonna, and also in the same year a document attests that his father Giovanni rented a brigantine to go and fetch Antonello together with some family members (including his wife and son) to Amantea, on the coast of Calabria: however, we do not know from where the painter returned, nor do we know the reason for his journey.

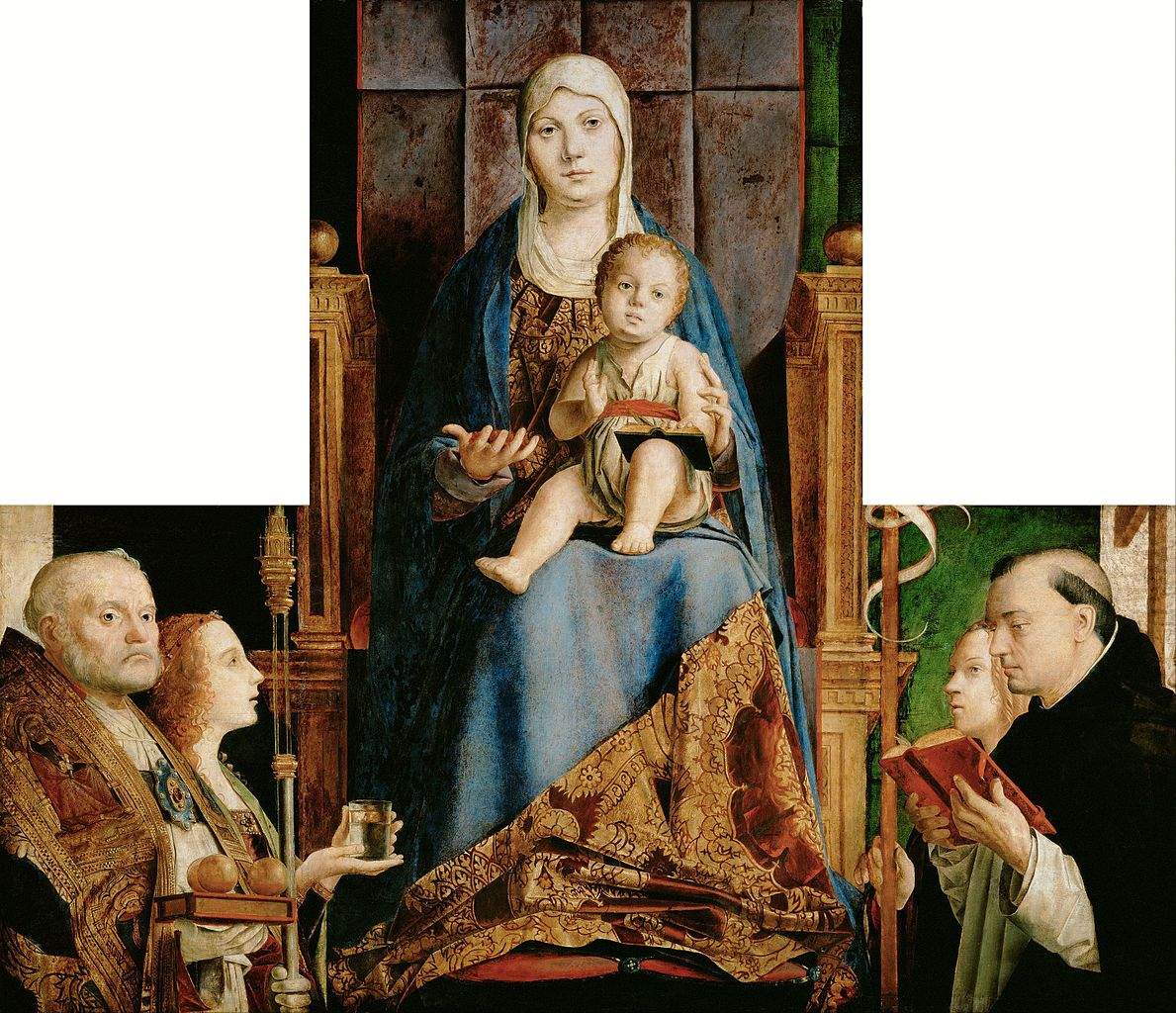

The Blessing Christ (also known as Salvator Mundi) in the National Gallery in London appears to be dated 1465, but we do not know if it was actually painted in 1465. Around the same year he painted the Portrait of a Man in the Mandralisca Museum in Cefalù. By contrast, theEcce homo in the National Gallery of Palazzo Spinola in Genoa dates from about five years later. The Polyptych of Saint Gregory, on the other hand, is from 1473, and the following year the artist probably made the famous Saint Jerome in the studio. In 1475 Antonello stayed in Venice, where he stayed for at least a year. In the same year the Venetian patrician Pietro Bon commissioned from him the celebrated San Cassiano Altarpiece. He probably returned to Messina in 1476, and here spent the last years of his life. In the same year he painted the Trivulzio Portrait. Again in 1476 the Duke of Milan, Galeazzo Maria Sforza invited him to the Lombard city, where, however, Antonello in all probability never went. In 1478 the Scuola di San Rocco was founded in Venice: for their altar in the church of San Giuliano the artist had painted the St. Sebastian now in the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden (it is not clear, however, whether he painted it during his Venetian stay, or on his return to Sicily). The dying artist drew up his will on February 14, 1479, asking to be buried in a friar’s habit. On February 25 he is declared dead. His artistic legacy will be collected by his son, Jacobello d’Antonio (? - before 1488), destined, however, to disappear a few years after his father, probably at a young age.

|

| Antonello da Messina, Crucifixion (c. 1450-1460; tempera and oil on panel, 39 x 22.5 cm; Sibiu, Brukenthal Museum) |

|

| Antonello da Messina, Portrait of a Man known as Ritratto Trivulzio (1476; oil on panel, 37.4 x 29.5 cm; Turin, Museo Civico di Palazzo Madama) |

|

| Antonello da Messina, Annunciation (c. 1476; oil on panel, 45 x 34.5 cm; Palermo, Palazzo Abatellis, Regional Gallery) |

Antonello’s earliest known works include the two panels from Reggio Calabria, probably executed as pendants: they depict a penitent Saint Jerome and a visitation of angels to Abraham (the panel with Abraham, however, is missing one part, the one with the figure of Abraham). From these works we can already see some of the original features of Antonello da Messina’s painting: for example, in the case of the Saint Jerome, the setting in a rocky landscape typical of paintings from the Flemish area. Around the same period, between the 1950s and the 1960s, dates the Crucifixion of Sibiu: in the background, moreover, appears a view of Messina. The work is inspired by Flemish precedents and in particular draws inspiration from Jan van Eyck’s Crucifixion preserved at the Metropolitan Museum in New York: one can see the same crosses, which are very tall and contribute to an elevated viewpoint; the figures of the thieves, which derive from those of van Eyck because the good thief on the left is quiet almost like Christ, while the bad thief, i.e., the one on the right, is struggling; the rocky landscape is taken from paintings of the Flemish area, just as of Flemish derivation are the figures of the mourners at the foot of the cross (a vesita woman in a black dress and white veil is dressed exactly like another woman who in van Eyck’s work appears just above the Madonna). Another interesting and novel detail is that Christ is actually the only one nailed to a cross: the thieves, on the other hand, are crucified directly on the bare trunks of trees, and this way of representing them in contorted poses was also typical of Nordic painting. Again, some reference to the clear colors of Enguerrand Quarton’s Provençal painting could also be discerned in the landscape. There are, however, elements typical of the Italian tradition, primarily the statuesqueness of the bodies on the cross and the scanning of space that would suggest that Antonello was familiar with the principles of scientific perspective that had been developed precisely in Italy not long before.

Antonello’s art would later know a further evolution with the Madonna Salting, whose volumetries might derive from the art of Piero della Francesca, whose ordered and idealized, almost abstract beauty Antonello reproposes. Piero Francesca’s culture represents the most “Italian” element of this work by Antonello. Made certainly for private devotion, the beautiful Salting Madonna has very refined and very delicate features that several scholars have related to the work of Enguerrand Quarton; in particular, the features of Antonello’s Madonna resemble those of the Madonna that appears in the Provençal painter’s Coronation of the Virgin. The other two striking elements are the dark background, which was typical of contemporary Flemish portraiture (see, for example, Van Eyck’s portraits), which will also be a constant in Antonello da Messina’s portraits and generally in all his half-length figures.

This work leads directly to Antonello’s portraiture, an area in which the artist was a great innovator, having brought to Italy the characteristics of Flemish portraiture: three-quarter face, dark background, light striking the right side of the figure. Moreover, Antonello succeeded in infusing his portrayed subjects with a psychological analysis that is unparalleled in all fifteenth-century painting. It is precisely in portraiture that we appreciate one of Antonello da Messina’s most original and interesting strands. The journey through Antonello da Messina’s portraiture could begin with the Portrait of a Man of about 1465 that is in the Mandralisca Museum in Cefalù and that scholars say should be the first portrait painted by Antonello da Messina, although we have no certainties about it. It is not known who the person depicted is, but given the clothing it is assumed to be a wealthy person. The viewer is struck by the character’s almost ironic expression, with his smile that seems almost mocking: it is a demonstration of how Antonello wanted to combine physical verisimilitude with an equally thorough psychological analysis of the subject depicted. Another interesting portrait is the Trivulzio Portrait, which stands out for its accurate study of volumetries, capable of making the portrait very realistic, so much so that it is one of the peaks of all fifteenth-century portraiture. This study of volumetry represents the typically Italian component of Antonello’s portraiture and is one of the reasons why his portraits are so interesting and appear so realistic: this very solid volumetry comes from his study of the works of Piero della Francesca. In the painting (dated 1476: it owes its name to the fact that in ancient times it was in the Trivulzio collection), one can also notice the intense inner investigation performed by the painter, with an elusive, ambiguous, almost contemptuous expression (one of the most interesting features of Antonello’s portraits consists precisely in the fact that each subject has its own peculiar expression).

Another of Antonello’s most interesting works is theAnnunciata in the Regional Gallery of Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo: it is a half-length portrait emerging from the dark background, with a figure characterized by pierfrancesque volumetries, but it is also interesting to note the hands, with the very natural gesture of the left hand holding the veil at breast height, while the other would seem to be addressing the viewer, perhaps a gesture of surprise at the archangel Gabriel, whom the viewer does not see but who one must imagine has just arrived in Mary’s room. It is a hand that suggests movement, an element that lends dynamism to a work that without this detail would perhaps not have the same innovative scope(read a detailed discussion of Antonello da Messina’sAnnunciata here). Finally, as far as the Venetian sojourn is concerned, it is possible to mention the San Cassiano Altarpiece, of which today unfortunately only three fragments remain that have been reunited and are in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. This is a work destined to have a strong impact on later art (it was, for example, an important model for Giovanni Bellini). Antonello constructs a unified space with a very accurate perspective study, and this is also thanks to the setting in an apsidal basin, according to a conception that seems to derive directly from Piero della Francesca’s Montefeltro Altarpiece, which Antonello may have been familiar with. The saints are no longer arranged frontally as was the case in earlier paintings, but are arranged in a hemicycle, and this detail helps to suggest to us the depth of space in a really decisive way. To this study of perspective, entirely new in Antonello da Messina, which was derived from a careful analysis of the work of Tuscan painters, above all the aforementioned Piero della Francesca, we need to add the luministic effects, and in addition we notice a chromatic range that, in accordance with the results achieved by the Venetian painting of Giovanni Bellini (from whom Antonello in turn drew important cues), begins to become more delicate and soft.

|

| Antonello da Messina, Madonna Salting (c. 1460; tempera and oil on panel, 43.2 x 34 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

| Antonello da Messina, San Cassiano Altarpiece (1475-1476; oil on panel, 115 x 135.6 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum) |

The corpus of works by Antonello da Messina is very sparse. Few of his works can be seen in local museums in Sicily. The Regional Museum of Messina houses one of the most recent acquisitions in Antonello’s catalog, the Madonna with the Blessing Child and a Franciscan in Adoration, painted on the back with a Head of Christ in Pity, as well as one of Antonello’s greatest works, the Polyptych of San Gregorio. In Syracuse, at Palazzo Bellomo, theAnnunciation can be seen, while the Mandralisca Museum in Cefalù holds the very famous Portrait of a Man, and finally the Regional Gallery of Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo holds perhaps Antonello’s most poetic work, theAnnunciation, and some polyptych cusps. In Italy, Antonello’s works can be seen at the Pinacoteca Civica in Como (the Virgo advocata), at the Poldi Pezzoli in Milan (the Vergine leggente), at the Pinacoteca Civica in Reggio Calabria (the San Girolamo penitente and the Visita dei tre angeli ad Abramo), at the Pinacoteca Malaspina in Pavia (the Portrait of a Man), at the Uffizi (the Polyptych of the Doctors of the Church), at the Museo Civico di Palazzo Madama in Turin (the Trivulzio Portrait), at the Galleria Borghese in Rome (a Portrait of a Man), and at the Museo Correr in Venice (the Christ in Pity). Two splendid Ecce Homo, finally, are kept at the Galleria Nazionale di Palazzo Spinola in Genoa and at the Collegio Alberoni in Piacenza.

Some of Antonello’s major masterpieces can also be admired abroad: among them, the youthful Crucifixion at the Brukenthal Museum in Sibiu, Romania; the Madonna Salting, Salvator Mundi and St. Jerome in the Study at the National Gallery in London; an Ecce Homo at the Metropolitan Museum in New York; theAnnunciation at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, the famous fragment of the St. Cassian Altarpiece at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Crucifixion at the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp, the St. Sebastian at the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden, the Christ in Pity and an Angel at the Prado in Madrid, and the Christ at the Column at the Louvre.

|

| Antonello da Messina, life and works of the great Sicilian painter |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.