Fortunato Alberto Lorenzo Depero (Fondo, 1892 - Rovereto, 1960) was one of the leading exponents of the Futurist movement, the most prominent artistic avant-garde in early 20th-century Italy. Depero was instrumental in the development of so-called Second Futurism, the second phase of the art movement. Second Futurism was distinguished from the first by a greater fusion of art and reality; it was inaugurated in 1915 by Giacomo Balla (Turin, 1871 - Rome, 1958) and Depero with the writing of the Manifesto of the Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe. In the Manifesto, Depero and Balla declared themselves abstract futurists and set as their goal the birth of an art that would involve every aspect of practical life. Through the fusion of art with everyday life, the Futurists would brighten the universe by recreating it in its entirety. To achieve this goal, artists were to take inspiration from the ’intangible, and then combine it with their inspiration, thus giving rise to plastic complexes. These were the new Futurist works, which would supplant previous art through the use of innovative materials and the combination of hitherto separate techniques.

The Manifesto of the Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe demonstrates the revolutionary and innovative charge of Fortunato Depero’s work. Indeed, the Roveretan was a great experimenter and sought to take his art among the people and into the streets, applying the principles of futuristic artistic research to different fields of art and production. To achieve this goal, Depero did not limit himself to classical artistic pursuits, such as painting, sculpture and architecture, but was involved in the production of tapestries, stage designs, advertising campaigns and pavilions.

Fortunato Alberto Lorenzo Depero was born in 1892 in Fondo, in the province of Trento, from the marriage of Lorenzo Depero and Virginia Turri. After a short time the family moved to Rovereto, where Fortunato pursued his studies at the Scuola Reale Elisabettina, an art institute. During these formative years the young man trained as a sculptor and traveled to Turin to work as a decorator at the ’Esposizione Universale.

In 1913 Depero completed his studies at the institute, and at the end of the same year he traveled to Rome to visit the exhibition of Umberto Boccioni (Reggio Calabria, 1882 - Verona, 1916), organized by gallery owner Giuseppe Sprovieri. During this occasion the young artist came into contact with the Futurist movement, from which he never again detached himself. In February 1914 Depero returned again to Rome, where he had the opportunity to meet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (Alexandria, Egypt, 1876 - Bellagio, 1944), the founder of the Futurist movement, and many other artists, including Giacomo Balla. In addition, Sprovieri allowed him to exhibit at the International Futurist Free Exhibition.

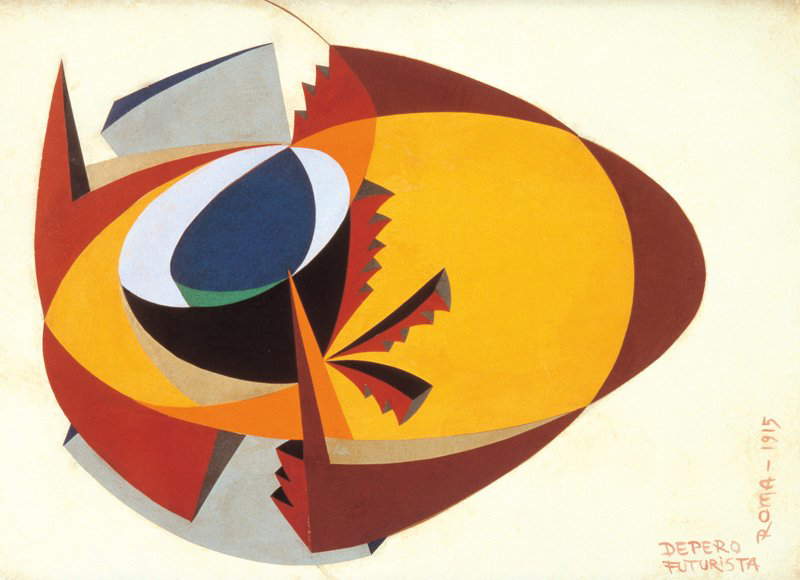

At the outbreak of World War I, Fortunato went to the front, where he stayed for a short time, as he was exonerated due to health problems. Thus, Depero settled in Rome, where he began working with Balla. On March 11, 1915, the two artists published the Manifesto of the Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe, with which the Second Futurism began. During this period Depero’s artistic production was characterized by strong abstractionism. However, as early as the same 1915, the young futurist began his gradual return to figuration, visible in the design of a toy: Kikigolà, a rooster with bright chromatic tones and plastic lines.

In 1916 the impresario of the famous Ballets Russes, Sergej Pavlovič Djagilev (Selišči, 1872 - Venice, 1929), visited Fortunato Depero’s studio and commissioned him him the stage and costume fittings for the play The Nightingale’s Song, to music by Igor’ Fyodorovič Stravinsky (Lomonosov1882 - New York, 1971). However, Depero never completed the work for Djagilev because he was too busy helping Pablo Ruiz y Picasso (Malaga, 1881 - Mougins, 1973) in making costumes for the stage show Parade.

Thus began the close connection between Depero and the world of theater, which was consolidated in 1917 when he met the Swiss poet Gilbert Clavel (Kleinhüningen, 1883 - Basel, 1927). Clavel commissioned the futurist to do illustrations for his book An Institute for Suicides. In April 1918 the two artists began work on a new project: the Teatro Plastico, with which Depero fully entered the experiences of the early 20th-century avant-garde. Plastic theater aimed to revolutionize ordinary theater through the replacement of actors with wooden puppets, more like automatons than people. The first performance was staged in Rome in 1918 under the name Balli Plastici. Also in 1917 Depero made his famous Futurist tapestries for the first time, or mosaics of colored fabrics of different materials, on which fabulous and magical worlds were depicted.

In the spring of 1919, Depero returned to Rovereto, where he devoted himself to the realization of a new idea: the Futurist Art House. The latter was conceived with the aim of producing various types of furniture products for a new Futurist home, so as to replace the outdated furnishings that occupied European homes. In the 1920s Depero received several commissions, such as the setting up of the Cabaret del Diavolo in Rome, a Dante-themed bar. The most important event of these years was his participation in the 1925Exposition internationale des Arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris, during which he had the opportunity to expand his horizons beyond the Italian borders. In 1926 Depero also exhibited at the 15th Venice Biennale, where he presented the oil painting Squisito al selz, dedicated to Commendator Campari, with whom he began a partnership that led to the birth of one of Italy’s most successful products, Campari Bitter.

In 1927 a new book of his saw the light of day: Revolutionary Depero futurist. It was a book-object relegated with two bolts, designed as a self-celebration of his artistic activity and an occasion to praise the machine, a favorite theme of the Futurists. The following year the artist went to New York, where he worked in various fields, especially advertising. Depero was commissioned numerous covers for major magazines such as Vogue, Vanity Fair, and many others. Also during these years he signed the Manifesto of Futurist Aeropainting, a new artistic operation that aimed to represent works from the perspective of an airplane pilot. In return, Depero never devoted himself to creating works that fully responded to the manifesto’s directions.

In 1930 Fortunato returned to Italy, where he was received with great enthusiasm by the other Futurists, to the point that Marinetti presented him as the “triumph of Futurism in America.” In 1932 Fortunato drafted the Manifesto of Futurist Advertising Art, with which he crowned all his advertising campaigns. After that, the artist retired to Rovereto, where young futurists visited him in admiration. During the 1930s Depero began to relate to the fascist regime, however, after the war the futurist artist declared that he collaborated with the party solely for economic reasons. During this period, in Rome Fortunato produced the mosaic Le Professioni e le Arti (1942) and in 1943 he published A passo romano, a collection of warrior lyrics that the artist said were written in an attempt to ingratiate himself with local hierarchs. Fortunato devoted the last years of his life to the creation of the first Futurist museum, which was opened to the public in 1959. However, the artist could not take part in the ceremony due to health problems, which led to his death after a few months.

Fortunato Depero’s training was influenced by several sources: firstly, he was fascinated by the decorativism and elegance of the Viennese Secession, and secondly, Depero was impressed by the moralism of Goya’s whimsy. The result of these studies led to the composition of works in which masculine, sculptural subjects and dense, oily painting, typical of the Alpine area, were represented.

Depero’s art was revolutionized by his encounter with the Futurist movement and in particular the works of Giacomo Balla. As mentioned above, the two theorized the Manifesto of the Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe. Depero’s works between 1914 and 1916 were characterized by a pronounced abstractionism and a light palette, which at the same time managed to combine with a strong volumetry of surfaces. Among Depero’s abstract works are Ciz-Ciz-quaglia (1915) and Movimento d’uccello (1916): in both paintings the figurative element is absent, but it is possible to trace analogies with the animal world and with the ’explosiveness of Futurist poetics, through the garish and solid colors.

Depero returned to figuration after a few years, and between 1916 and 1917 he produced some of the most important works of his entire artistic career. In fact, the first futuristic tapestries date from this period, which came about by chance while working on the failed Ballets Russes project. During these years Depero had been making sets with collages of colored papers, and given the large supply of colored textiles left unused for The Nightingale’s Song, he had the idea of replacing the collage papers with excess cloth. Initially, these were collages of cloth on a cardboard backing, which only later was replaced by needle and thread. The subjects of the tapestries were the same as the plastic dances, namely automata, immersed in a colorful and completely mechanized world. Among the most famous tapestries appears the Feast of the Chair (1927), in which automata, immersed in an enchanted landscape, stage a dance in honor of a singularly shaped chair. Some elements of popular culture dear to Depero appear in the work, and in the background are pavilions reminiscent of designs made for advertising campaigns.

The theatrical universe imagined by Depero and Clavel, staged only a year later, had a fundamental impact on the futurist’s art. In fact, plastic dances were a constant source of inspiration for every field of his artistic research, as in the case of the oil painting My Plastic Dances (1918). The canvas depicts the staging of a play, restoring to the viewer the theatrical experience he had at the time.

In August 1918 Fortunato Depero traveled to Viareggio where he perfected the Teatro Plastico with the creation of the Teatro Magico. The futurist replaced the clumsy wooden puppets with an actor on stage who could move with greater agility and ease, resembling a little devil with snappy movements, which the artist depicted in the painting Caoutchouc Devils (1919). The stay at the Tuscan city was very important because it brought the artist into contact with the metaphysical masterpieces of Giorgio de Chirico (Volos, 1888 - Rome, 1978). Contact with the new artistic current led him to create works in which the mysterious and silent aura of metaphysical poetics merged with the vividness of Depero’s tapestries. Among these works is La Ciociara (1919), a painting in which a woman of humble origins is depicted in the foreground. The canvas is characterized by a strong plasticity of volumes and an accentuated geometrization of forms, which are enveloped in a mysterious metaphysical halo.

Fortunato Depero played a fundamental role in the advertising revolution, focusing on the use of typeface as a graphic element, coordinated with certain visual choices. Among the most successful advertising campaigns was the collaboration between the futurist artist and Davide Campari’s eponymous company. Depero handled the advertising graphics and fittings for Campari. The happiest result of the Depero-Campari partnership was the design of the bottle packaging for Campari Soda. The futurist thought of the container in the shape of a loudspeaker, a subject typical of futurist artists as a symbol of strength. Depero chose to directly imprint the company’s trademark on the glass to ensure maximum transparency of the electric red product, a symbol of human manipulation on nature. In this all-round collaboration between Depero and Campari, it is possible to glimpse a glimpse of the union between industrialists and designers in the 1980s that gave birth to Made in Italy.

Fortunato Depero was a well-rounded artist, who did not limit himself solely to the more common areas of art, but devoted his entire life to experimentation and the creation of works in which craftsmanship and art mingled, resulting in masterpieces of extreme quality. Today there is a reappraisal of Depero’s work, which for years was sidelined because of his collaboration with the fascist regime.

The best place to view Depero’s works is La Casa d’Arte Futurista in Rovereto, founded by the artist himself. Inside the museum you can see more than 3,000 masterpieces by the Futurist genius and the original structure of the house designed by Depero, which was recovered thanks to a complex restoration by architect Renato Rizzi. The museum houses some of the futurist master’s most famous masterpieces, such as the Chair Party, the painting Diabolicus (1924-1926) and others. In addition, there are entire rooms decorated with frescos and decorative panels painted in oil or tempera, as in the case of the Rovereto Room, in honor of the municipality that accepted Depero’s proposal for a museum.

Only ten minutes from this complex it is possible to see more of Depero’s works at the MART (Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art). Among the masterpieces of the Rovereto master kept at the museum are some of the early results of Depero’s artistic research, for example the 1912 Woodcutter. In addition, Depero’s works can also be contemplated in other Italian museums, such as the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Turin, the Giuseppe Verzocchi Collection in Milan, and the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome. Finally, some of the Futurist master’s works are also preserved outside Italy, for example at the Gallery of Modern Art in Baltimore and the Diahileff Collection in Paris.

|

| Fortunato Depero: the life and works of the futurist master |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.