Mimmo Rotella (Catanzaro, 1918 - Milan, 2006) was one of the most active Italian artists within the Nouveau Réalisme movement that developed in the 1960s. To frame his art, it is necessary to look at the art scene of the 1950s, when progress was perceived negatively and positively, according to many different scenarios. The 1950s thus witness a return to the object, an interest declined by the various currents. In England, the human figure is deformed (this can be seen, for example, in the art of Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Henry Moore): this is because, after World War II, the artists mentioned are in the grip of despondency, pervaded by a sense of emptiness and unable to see progress as a solution. On the contrary, a return to the object, in a positive sense, occurs with Nouveau Réalisme: in the 1950s the artists who adhere to it perceive in progress the possibility of more advanced experimentation, although they also channel their interest on the object like the English.

Attention is turned to consumerist society and the means by which the product is promoted (studying marketing techniques, through effective advertising posters). Artists are no longer strangers to their audience, but want to involve the viewer, bringing him or her inside the creative process that leads the artist to create his or her work. The main figure in Italian art of these years is Piero Manzoni, creator of multiple artistic provocations (the ninety boxes of Merda d’artista are an example). Attention to everyday objects and the opening of art to the various aspects of life are concepts on which the American New Dada worked (Manzoni himself is considered by some to be a New Dada), but before that the French Marchel Duchamp with his ready-mades already in the 1910s. It was from these experiences that Nouveau Réalisme developed, a movement consisting of heterogeneous personalities united by the desire to reappropriate the real dimension. The artists who adhere to it are led by the critic Paul Restany, to whom we also owe the name of the movement; Mimmo Rotella joins in 1961, along with Yves Klein, Arman, Daniel Spoerri, and Jean Tinguely, and a few years later César, Niki de Saint-Phalle, and Christo. The movement developed parallel to the American New Dada experience, bringing a wave of novelty to the world panorama of contemporary art.

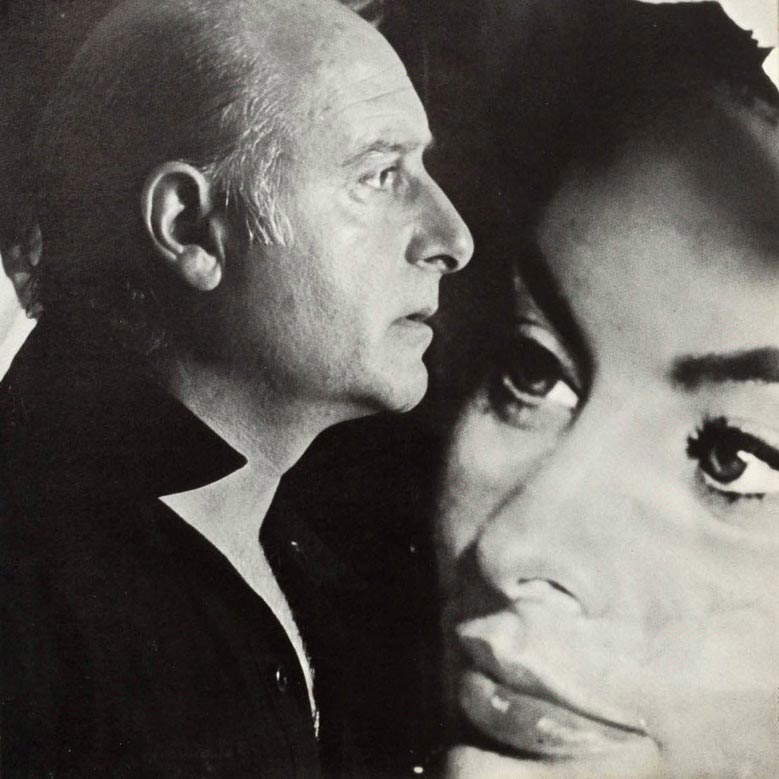

|

| Mimmo Rotella in 1975 |

Mimmo Rotella was born in Catanzaro, Italy, on October 7, 1918, coming from a middle-class family. After graduation he enlisted in the army, from which he was discharged in 1943. He then enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Naples, where he graduated in 1944. The following year, 1945, saw him in Rome, where he remained until 1950; here he met the artists of the Italian Avant-Garde. Thanks to various collaborations with Roman galleries such as Plinio De Martiis’s La Tartaruga and Gian Tomaso Liverani’s La Salita, he achieved notoriety as early as the 1950s. Rotella, during his career, collaborated with not only Italian, but also American and French artists, allowing him to take his art all over the international territory.

In 1951 he organized his first solo exhibition at the Galleria Chiurazzi, also in Rome; in the same year he won a scholarship that allowed him to fly to the United States, where he attended the University of Kansas City; here he produced some important works, such as the large mural for the Physics and Geology department of the University, as well as exhibiting at the Nelson Gallery: a fortunate year, followed, however, by a crisis for the artist, already returning to Rome in 1953. In 1953 he experimented with his first décollages, posters torn from the walls and then further torn in the studio. In the following years he always exhibited in the capital, and in 1957 he held a solo show in Milan, at the Naviglio gallery. The new technique began to be highly appreciated by critics, gallery owners, giving the artist the opportunity to exhibit in group or solo shows. His fame, in parallel, grows; his works reach Zurich, London, Venice, New York and again, in 1959, Tokyo, Lima, Mexico, Slovenia. Joining the Nouveau Réalisme in 1961 also led the artist to exhibit in the French scene. Memorable is his participation in the Nice Festival, on the occasion of the group’s presentation: a few years later, in 1964, he moved to Paris. Mec-Art was born, a process in which the artist projects negatives of images onto canvas. He participates in the XXXII Venice Biennale, where he has the honor of having a room exclusively for his works. The culmination of Mec-Art is the 1965 series Artypo, a term coined from the words art and typographie.

In 1967 he traveled to New York, hosted by the artists Christo and Jeanne Claude(read an in-depth look at these two great artists here), where he met Andy Warhol, a leading exponent of Pop Art, a mass culture movement that originated in England in the 1950s and came to America in the 1960s. Rotella, who is already familiar with it, is fascinated by the manipulation of images and the techniques of manipulation and deformation, used by Warhol. In the following decade he continued to exhibit with Nouveau Réalisme artists, in Milan, and in 1972 he published Autorotella. Autobiography of an Artist. The following year Tommaso Trini wrote a monograph on his art, attempting to explain the many techniques he used. In 1978 he again participated in the Venice Biennale, continuing to exhibit his Mec-Art works. In the 1980s, which saw his move to Milan, he is engaged in the blanks series and in portraying film and fashion personalities, a new world the latter, but one that allows him to mount an exhibition in London, in the Victoria and Albert Museum. He continued to exhibit at the Castello di Rivoli, in Sicily, in Paris, and in 1986 he was in Havana for the Biennale. In 1988 he is in Moscow where he meets his future wife, Inna Agarounova; a happy marriage, which sees in 1993 the birth of their daughter, Aghnessa. Rotella, tireless, continues to exhibit in Paris, New York, Los Angeles, Milan, and Ferrara. In 2001, the Mimmo Rotella Foundation was established, and in 2002 he was again at the Venice Biennale, curated by Swiss art historian and exhibition curator Harald Szeemann.

Despite the many awards he received-two honorary degrees, the Gold Medal for Visual Arts, and the Gold Medal for Arts and Architecture-the artist continued to experiment with new techniques, embodied in the New Icons series, which was followed by the opening of an exhibition at the Beijing Academy of Fine Arts. The artist died on Jan. 8, 2006, in Milan, Italy, leaving a legacy of works spread throughout the world. On the occasion of the centenary of the artist’s death in 2018, Italy paid tribute to him through two initiatives: the City of Catanzaro, reclaimed the House of Memory to set up the exhibition Mimmo Rotella in the City. In Rome, at the National Gallery of Modern Art, a monographic retrospective was organized, with more than one hundred and sixty works, tracing the main techniques used by the artist.

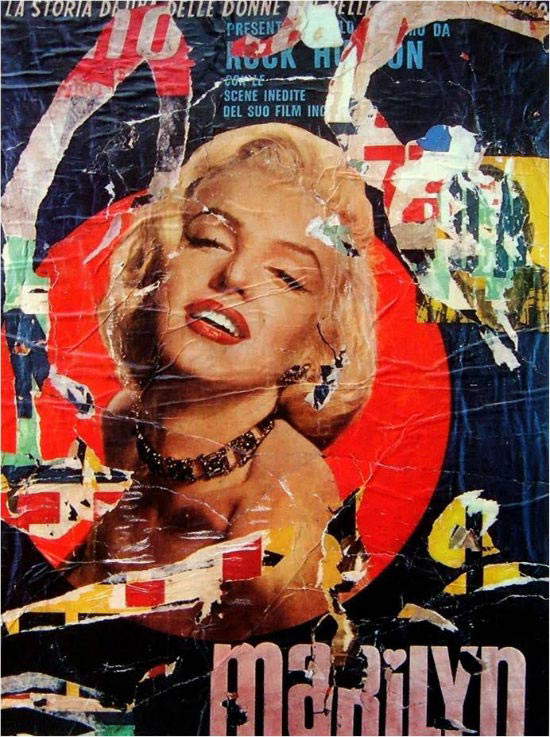

|

| Mimmo Rotella, Marilyn (1962; décollage on canvas, 133x94 cm; private collection) |

|

| Mimmo Rotella Manifesto, view of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art, Rome, 2018 (Ph.Credit Giorgio Benni) |

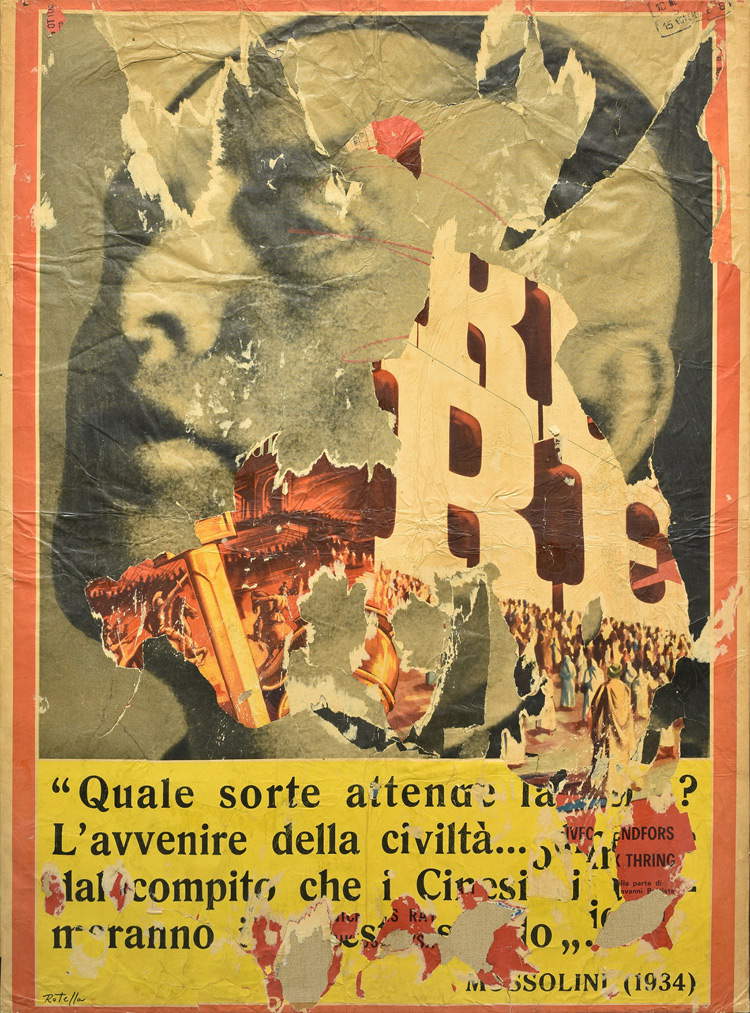

Rotella experiments with many techniques in his artistic career, but to arrive at his last series (the New Icons) his investigation begins by studying the great masters of the 20th century. In the early years of his career, he used traditional painting techniques, drawing inspiration from Cubism, Futurism and Vasily Kandinsky’s Abstractionism, arriving at an abstract-geometric style. As he became more and more aware, his interest moved closer to advertising graphics, eventually aligning himself with the pursuits of American Pop Art. The Roman gallery La Tartaruga, in addition to having supported Rotella from the beginning, is the first gallery to exhibit the famous décollages, one of his first series. To make them, the artist literally peels off pieces of posters hanging on city walls, then glues them onto canvases. The end result are fragmented, broken compositions, just like our collective imagination. Consumer society is constantly bombarded by advertising images (not only) and the work is meant to make us reflect on this concept as well. With the décollages Rotella makes a recovery of the advertising poster, against the consumerist society. In 1958 he moved on to figurative décollages, portraying faces of some movie stars, who became real icons.

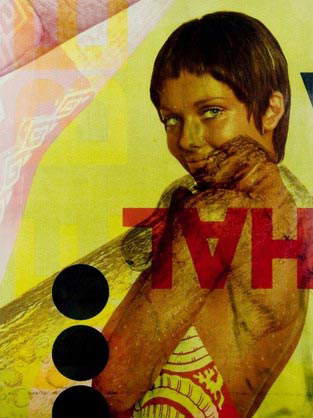

One of his best-known décollages is Marilyn, the Hollywood diva, an icon of beauty, beneath which lies a fragile personality, constantly subjected to a process of media violence. In 1963 he continued technical experimentation, making reportages or photographic reports, oriented toward the portrait dimension or through political figures, an interest that continued until the late 1970s. Another technique he uses for the artypos series, where the artist turns production waste, i.e., proofs for posters, into works of art. From reusing failed prints, he moves on to manipulating the image itself: this is the time of the frottages, works that involve reproducing objects by tracing the object itself on a sheet of paper. In 1980 he landed on blanks, the technique of coverings (Rotella takes a poster and pastes monochrome sheets on top of it).Toward the end of his career, Rotella also experimented with hybrid structures, a middle ground between sculpture/architecture, by fixing advertising posters on folded metal sheets.

Parallel to his artistic production, Rotella composed phonetic poems, elaborating in 1949 the Manifesto of Epistaltism, a child of Tommaso Marinetti’s Futurist manifestos. Also interesting in his career is the harmonious relationship between art and music, an imagery he always draws on.

|

| Mimmo Rotella, Hal (1971; artypo, 137 x 97cm) |

|

| Mimmo Rotella, The Last King of Kings (1961; décollage on canvas, posters, glue, 130 �? 97cm; ahlers collection) |

Rotella’s works are scattered all over the world. On the Italian scene, the Mimmo Rotella Foundation certainly represents a point of reference for the cataloguing and dissemination of the artist’s life and works. The Museo del Novecento in Milan houses the work Decisions at Sunset from 1961. Also in Italy to see some of his works, one must go: to Rome, to the Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, where we find Up Tempo of 1957; to MART in Trento and Rovereto; and to Venice to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection.

Rotella’s works are exhibited in all the most relevant museums dedicated to contemporary art.

Abroad, too, there are many opportunities to encounter his work, precisely because of the possibility of exhibiting in almost every major avant-garde institution. To name a few, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, The Solomon Guggenheim Museum and The Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery in Washington, the Tate Modern in London, Amsterdam, Lisbon and Buenos Aires.

|

| Mimmo Rotella, art and works of the exponent of Nouveau Réalisme |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.