By the beginning of the sixteenth century, the Republic of Venice had completed its expansionist phase on land, arriving at annexing to its territories a large portion of northern Italy that roughly corresponded to the present-day regions of Veneto, Friuli, eastern Lombardy (excluding Mantua) and Romagna. And in addition, with the annexation of the kingdom of Cyprus to the so-called Stato da Màr (i.e., the Venetian overseas territories) it had succeeded in expanding its maritime domains. Ambitious Venetian expansionism (also discussed above) also had its downsides: in order to conquer Romagna, Venice engaged in a struggle against the Papal States, which succeeded in creating a League of states (in which France and the Empire also participated) in an anti-Venetian key. La Serenissima suffered two resounding defeats in l509: on land, at the Battle of Agnadello, where it was defeated by the French, and at the naval battle of Polesella in which, on the waters of the Po, the Ferrara navy, commanded by Cardinal Ippolito d’Este, a strategist and brother of the Duke of Ferrara Alfonso I, destroyed the Venetian fleet. Ferrara thus took revenge on Venice after losing to the latter in the so-called Salt War waged between 1482 and 1484.

The war lasted until 1515, with several reversals of alliances: at the end of the conflict, thanks to a shrewd diplomatic strategy, Venice managed to limit the damage. However, also aided by the discovery ofAmerica, which had opened new trade routes, and the growing weight of the Turks in the political and commercial dynamics of the Mediterranean, Venice suffered a decline in its maritime trade, although for a few decades it experienced a period of relative peace. The wars at the beginning of the century, however, had not lowered the level of hedonism of the Venetian patriciate, who towards the end of the 15th century began to develop their own philosophical thought, fueled by contacts with Italian regions where Neoplatonic culture was alive. However, Venetian patricians used the philosophical and mythological repertoire they had learned to create their own code of representation underlying the paintings they commissioned from artists: this language is still cryptic and difficult to decipher precisely because it is reserved for very restricted circles.

The painter who best embodied this spirit of the major Venetian families was a painter who did not come from Venice, but rather from the mainland, where, however, the Venetian patriciate had begun to go for their leisurely sojourns: this is Giorgione da Castelfranco (Castelfranco Veneto, 1478 - Venice, 1510), an extremely elusive and enigmatic painter but of capital importance for the developments of art in Italy. Giorgione’s real name is unknown (perhaps Giorgio Barbarelli) and there are only three documents about him. The culture of the Venetian milieu of the time finds fulfillment in many of Giorgione’s masterpieces, the most famous of which is probably the Tempest (c. 1502-1505) now in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice. A painting whose meaning, nowadays, is still not fully understood: there are several interpretations put forward, and at the current state of our knowledge, there are no hypotheses that can be discarded or accepted with certainty. This is because it is a cryptic painting from the very beginning, which was reserved for a small circle of viewers. This enigmatic nature characterizes much of Giorgionesque production (e.g., Saturn in Exile, also known as Homage to a Poet, c. 1496-1498, London, National Gallery), which was aimed primarily at private patrons, so much so that almost all of his paintings (with the exception of a very small number) are secular in subject. In each of them the artist revisits according to a certain language or philosophical thought elements drawn now from nature, now from the mythological repertoire. To give an idea of the type of Giorgione’s commissions, suffice it to say that there is only one painting of his preserved in a church, the Castelfranco Altarpiece (1503-1504, Castelfranco Veneto, Duomo).

But the particularities of Giorgione’s art were not limited to content, but also to technique. In fact, Giorgione perfected the so-called tonal painting. The Castelfranco artist was animated by the same desire as Leonardo da Vinci to investigate natural reality with a scrupulous eye, so much so that he approached Leonardo’s aerial perspective but reworked it on a typically Venetian basis. It has been said before that the Venetian school gave precedence to color over drawing: with Giorgione, art becomes pure color, and the sense of depth is given not only by the different degree of sharpness of objects as was the case with Leonardo, but also by thejuxtaposition of colors, which become colder as the object moves away from the viewer’s eye. An intuition, this, already developed by Giovanni Bellini and brought to fruition by Giorgione thanks also to Leonardo’s contribution. The result is that the color is spread out almost in a “blotchy” manner. Giorgione also took up from Leonardo the technique of sfumato to create objects whose forms were not sharply detached from the atmosphere around them, but blended with it. Nature, too, for Giorgione had no clear-cut forms, and in addition nature, for Giorgione, was composed essentially of colors, which through his own work the painter brought back into his art: this is the pinnacle of Venetian tonalism(or tonal painting), the painting in which the sense of depth is given by the juxtaposition of colors.

From these premises originated the art of Titian Vecellio (Pieve di Cadore, 1488/90 - Venice 1576), the most successful painter of 16th-century Venice, to the point that he annihilated all competition (so much so that Sebastiano del Piombo, not to compete with him, had to move to Rome). Titian came, like Giorgione, from the hinterland, but he lacked both grand and evocative refinement. Titian, who instead mastered a more dramatic, solid and powerful language(Miracle of the Jealous Husband, 1511, Padua, Scuola del Santo), used Giorgione’s achievements to enhance this component of his art: figures were constructed, as in Giorgione’s art, through color, which also matched the dramatic sense the work wanted to express (in Titian, bright colors, such as red and gold, are more prevalent), and succeeded in achieving an energy that Giorgione did not know and that proved better suited to a wider audience. Titian in fact worked not only for private individuals and limited circles, but was painter to sovereigns, princes, popes and emperors. Thus the concept on which the use of color is based is different: to create delicate atmospheres in Giorgione, to create solid volumes in Titian.

In addition to elaborating this language so powerful that it captivated the public, Titian had no small merit in renewing already established systems and schemes and revisiting the repertoires of tradition. In one of his seminal works such as the Pesaro Altarpiece completed in 1526 (Venice, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari), the artist creates a composition played out on diagonal lines, contrary to the classic frontal setting of the altarpiece, with the aim of extending the space of the painting far beyond the physical support (the canvas in this case). Evidence of this are the architectures that are truncated by the physical limits of the painting but that the viewer can imagine wider than the boundaries of the canvas. Like Giorgione, Titian also found himself executing allegorical paintings of unclear meaning (such as the very famous Amor sacro e amor profano, 1515, Rome, Galleria Borghese: read an in-depth discussion of the work here), albeit to a lesser extent than his predecessor, but Titian’s classicism was at its best in the production of mythological works for court patrons and, unlike Giorgione, often subordinated allegorical meaning to the expressive power of the work. Titianesque art would undergo conspicuous changes toward the end of his career, beginning in the 1650s, a period in which themes devoted to reflecting on the drama of life (especially in the mythological sphere: works such as Diana and Actaeon (1556-1559, Edinburgh, National Gallery of Scotland) and Apollo and Marsyas (c. 1571, Kromeríž, Arcibiskupský Zámek), in which even the forms and colors darken and become extremely tense, discordant, grainy, in an almost Impressionist procedure). The restlessness of Mannerism probably had also affected Titian’s art.

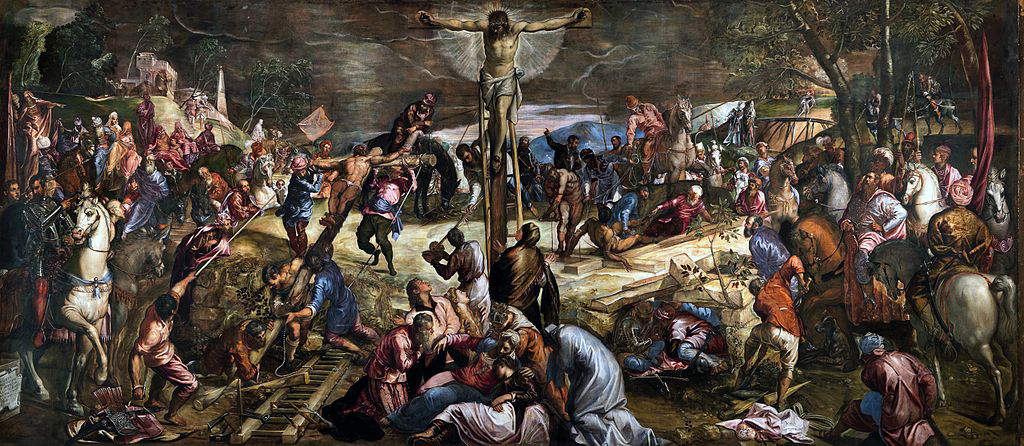

The masterpieces of the last two important exponents of the Venetian sixteenth century, who were already working in the age of Mannerism, were inspired by the previous experiences: Jacopo Robusti known as Tintoretto (Venice, 1518 - 1594) and Paolo Caliari known as Veronese (Verona 1528 - Venice 1588). The former took Titian dramatism to the extreme, partly in the light of a reinterpretation of the Tuscan Mannerists who were active in the lagoon at the time. Tintoretto’s art is also full of extraordinary luministic effects: light is in fact the great protagonist of Tintoretto’s poetics as it emphasizes situations, makes forms and characters stand out, creates dynamism and increases the dramatic charge of the scenes(Miracle of the Slave, 1548, Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia). This was a revolutionary art for the time, whose effect of emotionally involving the viewer, one of the goals of Tintoretto’s poetics, was achieved precisely through the strong dynamism and dramatic use of light. So dramatic that he often also became visionary, as happens in the grandiose Crucifixion in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco (1565) or even in theLast Supper in the Basilica of San Giorgio Maggiore (1592-1594), also in Venice, a work in which the flying angels seem almost like evanescent ghosts.

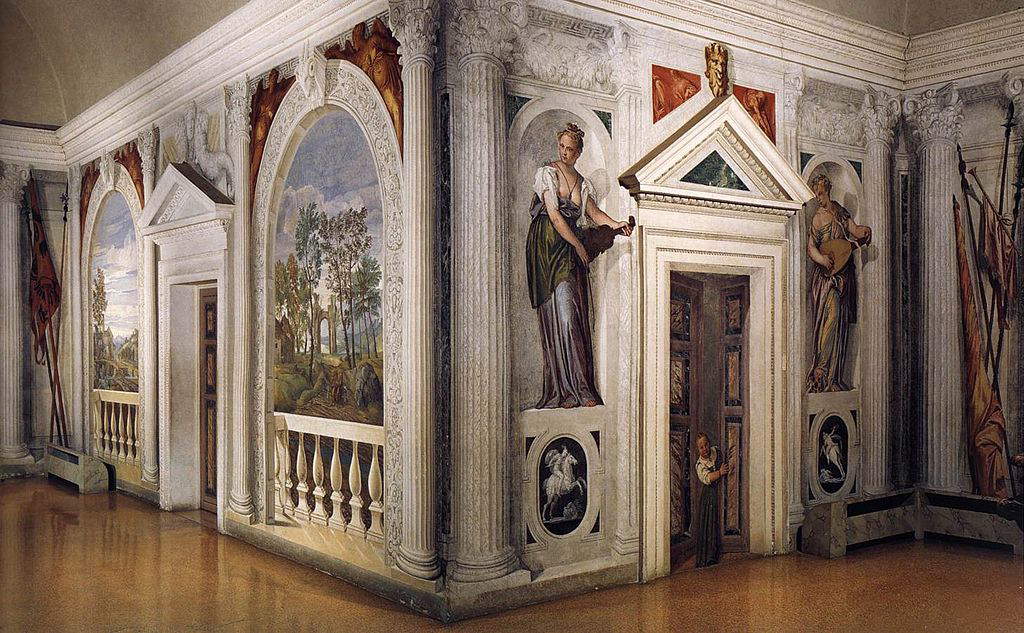

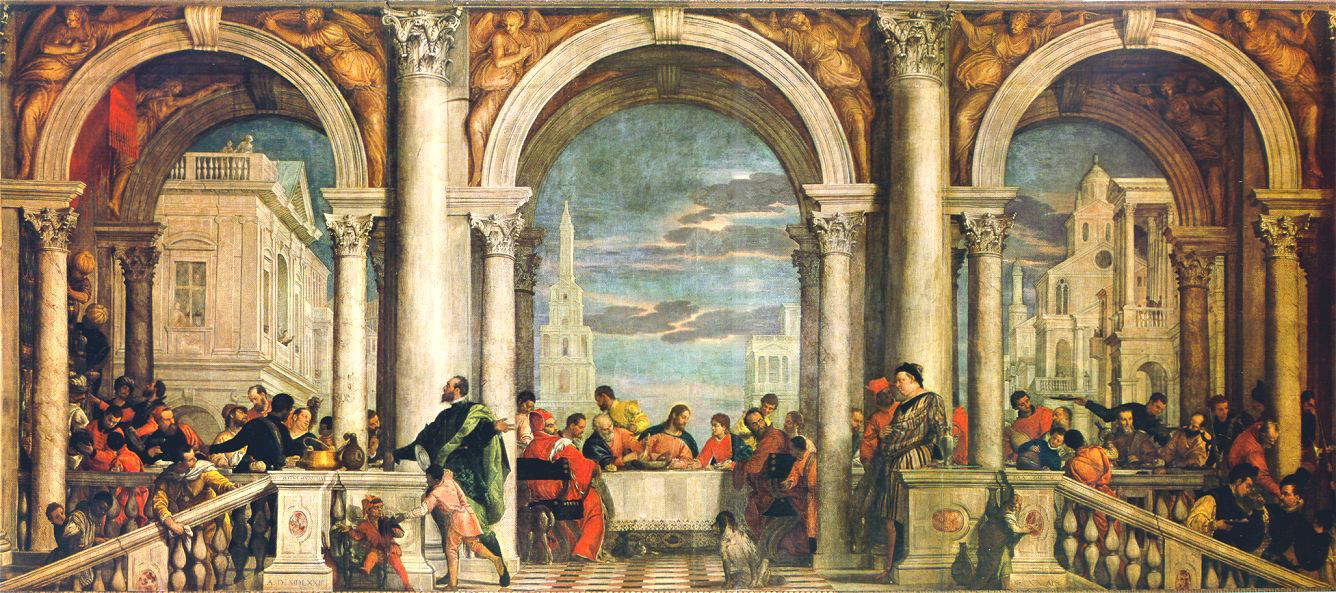

Completely different, however, was Veronese’s art. How dramatic and tense Tintoretto was, how calm and classical Veronese was. The latter started from the lively naturalism of Titian’s chromaticism and fused it with a renewed study of perspective, which the artist employed to create illusionistic compositions such as those at Villa Barbaro in Maser, where painted architecture breaks through the walls in an illusionistic manner, picking up a tradition that, from Mantegna onward, had never quite died down. Veronese’s atmospheres did not know the almost violent charge of Tintoretto’s, but they were characterized by bright, limpid colors that lent serenity to the scenes. It was a painting that accorded with the taste for luxury of the Venetian patriciate: this is demonstrated by a work such as Supper in the House of Levi (1573, Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia), with its strong scenographic impact andostentation of luxury. It was precisely these tendencies that led the painter to be tried for heresy: the artist was accused of having rendered too “profane” a painting with a sacred subject, aLast Supper, which, following the fortunately mild sentence passed against Veronese, underwent a series of changes that transformed it into, precisely, the Supper in the House of Levi.

The exceptional luminosity in Paolo Veronese’s paintings was also due to the peculiar intuition of using complementary colors, which, when juxtaposed, were able to provide greater brilliance to the composition. The use of complementary colors was nothing more than the juxtaposition of the primary color (red, yellow, blue) with the color given by the sum of the remaining two primary colors (red + green; yellow + purple; blue + orange). These colors, by reflecting, originated the white light, which gave brightness to the scene. This expedient (brought to fruition by elaborating on the insights of the Veronese school) also explains Paolo Veronese’s tendency not to make use of chiaroscuro.

|

| The sixteenth century Veneto. Art, developments, major artists |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.